полная версия

полная версияShakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth

(4) To these last arguments, which by themselves would be of little weight, I may add another, of which the same may be said. Marston's reminiscences of Shakespeare are only too obvious. In his Dutch Courtezan, 1605, I have noticed passages which recall Othello and King Lear, but nothing that even faintly recalls Macbeth. But in reading Sophonisba, 1606, I was several times reminded of Macbeth (as well as, more decidedly, of Othello). I note the parallels for what they are worth.

With Sophonisba, Act i. Sc. ii.:

Upon whose tops the Roman eagles stretch'dTheir large spread wings, which fann'd the evening aireTo us cold breath,cf. Macbeth i. ii. 49:

Where the Norweyan banners flout the skyAnd fan our people cold.Cf. Sophonisba, a page later: 'yet doubtful stood the fight,' with Macbeth, i. ii. 7, 'Doubtful it stood' ['Doubtful long it stood'?] In the same scene of Macbeth the hero in fight is compared to an eagle, and his foes to sparrows; and in Soph. iii. ii. Massinissa in fight is compared to a falcon, and his foes to fowls and lesser birds. I should not note this were it not that all these reminiscences (if they are such) recall one and the same scene. In Sophonisba also there is a tremendous description of the witch Erictho (iv. i.), who says to the person consulting her, 'I know thy thoughts,' as the Witch says to Macbeth, of the Armed Head, 'He knows thy thought.'

(5) The resemblances between Othello and King Lear pointed out on pp. 244-5 and in Note R. form, when taken in conjunction with other indications, an argument of some strength in favour of the idea that King Lear followed directly on Othello.

(6) There remains the evidence of style and especially of metre. I will not add to what has been said in the text concerning the former; but I wish to refer more fully to the latter, in so far as it can be represented by the application of metrical tests. It is impossible to argue here the whole question of these tests. I will only say that, while I am aware, and quite admit the force, of what can be said against the independent, rash, or incompetent use of them, I am fully convinced of their value when they are properly used.

Of these tests, that of rhyme and that of feminine endings, discreetly employed, are of use in broadly distinguishing Shakespeare's plays into two groups, earlier and later, and also in marking out the very latest dramas; and the feminine-ending test is of service in distinguishing Shakespeare's part in Henry VIII. and the Two Noble Kinsmen. But neither of these tests has any power to separate plays composed within a few years of one another. There is significance in the fact that the Winter's Tale, the Tempest, Henry VIII., contain hardly any rhymed five-foot lines; but none, probably, in the fact that Macbeth shows a higher percentage of such lines than King Lear, Othello, or Hamlet. The percentages of feminine endings, again, in the four tragedies, are almost conclusive against their being early plays, and would tend to show that they were not among the latest; but the differences in their respective percentages, which would place them in the chronological order Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello, King Lear (König), or Macbeth, Hamlet, Othello, King Lear (Hertzberg), are of scarcely any account.283 Nearly all scholars, I think, would accept these statements.

The really useful tests, in regard to plays which admittedly are not widely separated, are three which concern the endings of speeches and lines. It is practically certain that Shakespeare made his verse progressively less formal, by making the speeches end more and more often within a line and not at the close of it; by making the sense overflow more and more often from one line into another; and, at last, by sometimes placing at the end of a line a word on which scarcely any stress can be laid. The corresponding tests may be called the Speech-ending test, the Overflow test, and the Light and Weak Ending test.

I. The Speech-ending test has been used by König,284 and I will first give some of his results. But I regret to say that I am unable to discover certainly the rule he has gone by. He omits speeches which are rhymed throughout, or which end with a rhymed couplet. And he counts only speeches which are 'mehrzeilig.' I suppose this means that he counts any speech consisting of two lines or more, but omits not only one-line speeches, but speeches containing more than one line but less than two; but I am not sure.

In the plays admitted by everyone to be early the percentage of speeches ending with an incomplete line is quite small. In the Comedy of Errors, for example, it is only 0.6. It advances to 12.1 in King John, 18.3 in Henry V., and 21.6 in As You Like It. It rises quickly soon after, and in no play written (according to general belief) after about 1600 or 1601 is it less than 30. In the admittedly latest plays it rises much higher, the figures being as follows:—Antony 77.5, Cor. 79, Temp. 84.5, Cym. 85, Win. Tale 87.6, Henry VIII. (parts assigned to Shakespeare by Spedding) 89. Going back, now, to the four tragedies, we find the following figures: Othello 41.4, Hamlet 51.6, Lear 60.9, Macbeth 77.2. These figures place Macbeth decidedly last, with a percentage practically equal to that of Antony, the first of the final group.

I will now give my own figures for these tragedies, as they differ somewhat from König's, probably because my method differs. (1) I have included speeches rhymed or ending with rhymes, mainly because I find that Shakespeare will sometimes (in later plays) end a speech which is partly rhymed with an incomplete line (e.g. Ham. iii. ii. 187, and the last words of the play: or Macb. v. i. 87, v. ii. 31). And if such speeches are reckoned, as they surely must be (for they may be, and are, highly significant), those speeches which end with complete rhymed lines must also be reckoned. (2) I have counted any speech exceeding a line in length, however little the excess may be; e.g.

I'll fight till from my bones my flesh be hacked.Give me my armour:considering that the incomplete line here may be just as significant as an incomplete line ending a longer speech. If a speech begins within a line and ends brokenly, of course I have not counted it when it is equivalent to a five-foot line; e.g.

Wife, children, servants, allThat could be found:but I do count such a speech (they are very rare) as

My lord, I do not know:But truly I do fear it:for the same reason that I count

You know notWhether it was his wisdom or his fear.Of the speeches thus counted, those which end somewhere within the line I find to be in Othello about 54 per cent.; in Hamlet about 57; in King Lear about 69; in Macbeth about 75.285 The order is the same as König's, but the figures differ a good deal. I presume in the last three cases this comes from the difference in method; but I think König's figures for Othello cannot be right, for I have tried several methods and find that the result is in no case far from the result of my own, and I am almost inclined to conjecture that König's 41.4 is really the percentage of speeches ending with the close of a line, which would give 58.6 for the percentage of the broken-ended speeches.286

We shall find that other tests also would put Othello before Hamlet, though close to it. This may be due to 'accident'—i.e. a cause or causes unknown to us; but I have sometimes wondered whether the last revision of Hamlet may not have succeeded the composition of Othello. In this connection the following fact may be worth notice. It is well known that the differences of the Second Quarto of Hamlet from the First are much greater in the last three Acts than in the first two—so much so that the editors of the Cambridge Shakespeare suggested that Q1 represents an old play, of which Shakespeare's rehandling had not then proceeded much beyond the Second Act, while Q2 represents his later completed rehandling. If that were so, the composition of the last three Acts would be a good deal later than that of the first two (though of course the first two would be revised at the time of the composition of the last three). Now I find that the percentage of speeches ending with a broken line is about 50 for the first two Acts, but about 62 for the last three. It is lowest in the first Act, and in the first two scenes of it is less than 32. The percentage for the last two Acts is about 65.

II. The Enjambement or Overflow test is also known as the End-stopped and Run-on line test. A line may be called 'end-stopped' when the sense, as well as the metre, would naturally make one pause at its close; 'run-on' when the mere sense would lead one to pass to the next line without any pause.287 This distinction is in a great majority of cases quite easy to draw: in others it is difficult. The reader cannot judge by rules of grammar, or by marks of punctuation (for there is a distinct pause at the end of many a line where most editors print no stop): he must trust his ear. And readers will differ, one making a distinct pause where another does not. This, however, does not matter greatly, so long as the reader is consistent; for the important point is not the precise number of run-on lines in a play, but the difference in this matter between one play and another. Thus one may disagree with König in his estimate of many instances, but one can see that he is consistent.

In Shakespeare's early plays, 'overflows' are rare. In the Comedy of Errors, for example, their percentage is 12.9 according to König288 (who excludes rhymed lines and some others). In the generally admitted last plays they are comparatively frequent. Thus, according to König, the percentage in the Winter's Tale is 37.5, in the Tempest 41.5, in Antony 43.3, in Coriolanus 45.9, in Cymbeline 46, in the parts of Henry VIII. assigned by Spedding to Shakespeare 53.18. König's results for the four tragedies are as follows: Othello, 19.5; Hamlet, 23.1; King Lear, 29.3; Macbeth, 36.6; (Timon, the whole play, 32.5). Macbeth here again, therefore, stands decidedly last: indeed it stands near the first of the latest plays.

And no one who has ever attended to the versification of Macbeth will be surprised at these figures. It is almost obvious, I should say, that Shakespeare is passing from one system to another. Some passages show little change, but in others the change is almost complete. If the reader will compare two somewhat similar soliloquies, 'To be or not to be' and 'If it were done when 'tis done,' he will recognise this at once. Or let him search the previous plays, even King Lear, for twelve consecutive lines like these:

If it were done when 'tis done, then 'twere wellIt were done quickly: if the assassinationCould trammel up the consequence, and catchWith his surcease success; that but this blowMight be the be-all and the end-all here,But here, upon this bank and shoal of time,We 'ld jump the life to come. But in these casesWe still have judgement here; that we but teachBloody instructions, which, being taught, returnTo plague the inventor: this even-handed justiceCommends the ingredients of our poison'd chaliceTo our own lips.Or let him try to parallel the following (iii. vi. 37 f.):

and this reportHath so exasperate the king that hePrepares for some attempt of war.Len.Sent he to Macduff?Lord.He did: and with an absolute 'Sir, not I,'The cloudy messenger turns me his backAnd hums, as who should say 'You'll rue the timeThat clogs me with this answer.'Len.And that well mightAdvise him to a caution, to hold what distanceHis wisdom can provide. Some holy angelFly to the court of England, and unfoldHis message ere he come, that a swift blessingMay soon return to this our suffering countryUnder a hand accurs'd!or this (iv. iii. 118 f.):

Macduff, this noble passion,Child of integrity, hath from my soulWiped the black scruples, reconciled my thoughtsTo thy good truth and honour. Devilish MacbethBy many of these trains hath sought to win meInto his power, and modest wisdom plucks meFrom over-credulous haste: but God aboveDeal between thee and me! for even nowI put myself to thy direction, andUnspeak mine own detraction, here abjureThe taints and blames I laid upon myself,For strangers to my nature.I pass to another point. In the last illustration the reader will observe not only that 'overflows' abound, but that they follow one another in an unbroken series of nine lines. So long a series could not, probably, be found outside Macbeth and the last plays. A series of two or three is not uncommon; but a series of more than three is rare in the early plays, and far from common in the plays of the second period (König).

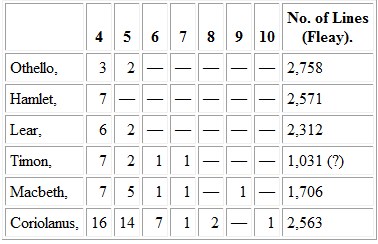

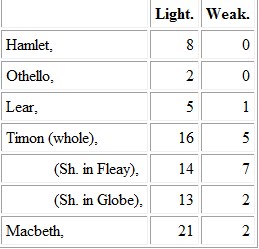

I thought it might be useful for our present purpose, to count the series of four and upwards in the four tragedies, in the parts of Timon attributed by Mr. Fleay to Shakespeare, and in Coriolanus, a play of the last period. I have not excluded rhymed lines in the two places where they occur, and perhaps I may say that my idea of an 'overflow' is more exacting than König's. The reader will understand the following table at once if I say that, according to it, Othello contains three passages where a series of four successive overflowing lines occurs, and two passages where a series of five such lines occurs:

(The figures for Macbeth and Timon in the last column must be borne in mind. I observed nothing in the non-Shakespeare part of Timon that would come into the table, but I did not make a careful search. I felt some doubt as to two of the four series in Othello and again in Hamlet, and also whether the ten-series in Coriolanus should not be put in column 7).

III. The light and weak ending test.

We have just seen that in some cases a doubt is felt whether there is an 'overflow' or not. The fact is that the 'overflow' has many degrees of intensity. If we take, for example, the passage last quoted, and if with König we consider the line

The taints and blames I laid upon myselfto be run-on (as I do not), we shall at least consider the overflow to be much less distinct than those in the lines

but God aboveDeal between thee and me! for even nowI put myself to thy direction, andUnspeak my own detraction, here abjureAnd of these four lines the third runs on into its successor at much the greatest speed.

'Above,' 'now,' 'abjure,' are not light or weak endings: 'and' is a weak ending. Prof. Ingram gave the name weak ending to certain words on which it is scarcely possible to dwell at all, and which, therefore, precipitate the line which they close into the following. Light endings are certain words which have the same effect in a slighter degree. For example, and, from, in, of, are weak endings; am, are, I, he, are light endings.

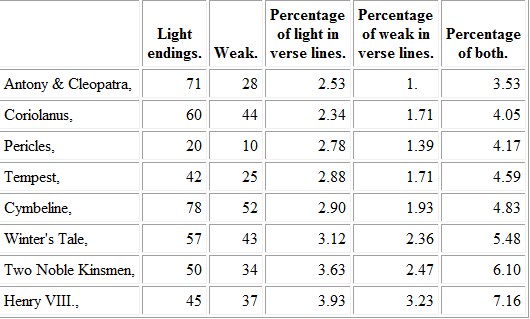

The test founded on this distinction is, within its limits, the most satisfactory of all, partly because the work of its author can be absolutely trusted. The result of its application is briefly as follows. Until quite a late date light and weak endings occur in Shakespeare's works in such small numbers as hardly to be worth consideration.289 But in the well-defined group of last plays the numbers both of light and of weak endings increase greatly, and, on the whole, the increase apparently is progressive (I say apparently, because the order in which the last plays are generally placed depends to some extent on the test itself). I give Prof. Ingram's table of these plays, premising that in Pericles, Two Noble Kinsmen, and Henry VIII. he uses only those parts of the plays which are attributed by certain authorities to Shakespeare (New Shakspere Soc. Trans., 1874).

Now, let us turn to our four tragedies (with Timon). Here again we have one doubtful play, and I give the figures for the whole of Timon, and again for the parts of Timon assigned to Shakespeare by Mr. Fleay, both as they appear in his amended text and as they appear in the Globe (perhaps the better text).

Now here the figures for the first three plays tell us practically nothing. The tendency to a freer use of these endings is not visible. As to Timon, the number of weak endings, I think, tells us little, for probably only two or three are Shakespeare's; but the rise in the number of light endings is so marked as to be significant. And most significant is this rise in the case of Macbeth, which, like Shakespeare's part of Timon, is much shorter than the preceding plays. It strongly confirms the impression that in Macbeth we have the transition to Shakespeare's last style, and that the play is the latest of the five tragedies.290

NOTE CC

WHEN WAS THE MURDER OF DUNCAN FIRST PLOTTED?A good many readers probably think that, when Macbeth first met the Witches, he was perfectly innocent; but a much larger number would say that he had already harboured a vaguely guilty ambition, though he had not faced the idea of murder. And I think there can be no doubt that this is the obvious and natural interpretation of the scene. Only it is almost necessary to go rather further, and to suppose that his guilty ambition, whatever its precise form, was known to his wife and shared by her. Otherwise, surely, she would not, on reading his letter, so instantaneously assume that the King must be murdered in their castle; nor would Macbeth, as soon as he meets her, be aware (as he evidently is) that this thought is in her mind.

But there is a famous passage in Macbeth which, closely considered, seems to require us to go further still, and to suppose that, at some time before the action of the play begins, the husband and wife had explicitly discussed the idea of murdering Duncan at some favourable opportunity, and had agreed to execute this idea. Attention seems to have been first drawn to this passage by Koester in vol. i. of the Jahrbücher d. deutschen Shakespeare-gesellschaft, and on it is based the interpretation of the play in Werder's very able Vorlesungen über Macbeth.

The passage occurs in i. vii., where Lady Macbeth is urging her husband to the deed:

Macb.Prithee, peace:I dare do all that may become a man;Who dares do more is none.Lady M.What beast was't, then,That made you break this enterprise to me?When you durst do it, then you were a man;And, to be more than what you were, you wouldBe so much more the man. Nor time nor placeDid then adhere, and yet you would make both:They have made themselves, and that their fitness nowDoes unmake you. I have given suck, and knowHow tender 'tis to love the babe that milks me:I would, while it was smiling in my face,Have pluck'd my nipple from his boneless gums,And dash'd the brains out, had I so sworn as youHave done to this.Here Lady Macbeth asserts (1) that Macbeth proposed the murder to her: (2) that he did so at a time when there was no opportunity to attack Duncan, no 'adherence' of 'time' and 'place': (3) that he declared he wou'd make an opportunity, and swore to carry out the murder.

Now it is possible that Macbeth's 'swearing' might have occurred in an interview off the stage between scenes v. and vi., or scenes vi. and vii.; and, if in that interview Lady Macbeth had with difficulty worked her husband up to a resolution, her irritation at his relapse, in sc. vii., would be very natural. But, as for Macbeth's first proposal of murder, it certainly does not occur in our play, nor could it possibly occur in any interview off the stage; for when Macbeth and his wife first meet, 'time' and 'place' do adhere; 'they have made themselves.' The conclusion would seem to be, either that the proposal of the murder, and probably the oath, occurred in a scene at the very beginning of the play, which scene has been lost or cut out; or else that Macbeth proposed, and swore to execute, the murder at some time prior to the action of the play.291 The first of these hypotheses is most improbable, and we seem driven to adopt the second, unless we consent to burden Shakespeare with a careless mistake in a very critical passage.

And, apart from unwillingness to do this, we can find a good deal to say in favour of the idea of a plan formed at a past time. It would explain Macbeth's start of fear at the prophecy of the kingdom. It would explain why Lady Macbeth, on receiving his letter, immediately resolves on action; and why, on their meeting, each knows that murder is in the mind of the other. And it is in harmony with her remarks on his probable shrinking from the act, to which, ex hypothesi, she had already thought it necessary to make him pledge himself by an oath.

Yet I find it very difficult to believe in this interpretation. It is not merely that the interest of Macbeth's struggle with himself and with his wife would be seriously diminished if we felt he had been through all this before. I think this would be so; but there are two more important objections. In the first place the violent agitation described in the words,

If good, why do I yield to that suggestionWhose horrid image doth unfix my hairAnd make my seated heart knock at my ribs,would surely not be natural, even in Macbeth, if the idea of murder were already quite familiar to him through conversation with his wife, and if he had already done more than 'yield' to it. It is not as if the Witches had told him that Duncan was coming to his house. In that case the perception that the moment had come to execute a merely general design might well appal him. But all that he hears is that he will one day be King—a statement which, supposing this general design, would not point to any immediate action.292 And, in the second place, it is hard to believe that, if Shakespeare really had imagined the murder planned and sworn to before the action of the play, he would have written the first six scenes in such a manner that practically all readers imagine quite another state of affairs, and continue to imagine it even after they have read in scene vii. the passage which is troubling us. Is it likely, to put it otherwise, that his idea was one which nobody seems to have divined till late in the nineteenth century? And for what possible reason could he refrain from making this idea clear to his audience, as he might so easily have done in the third scene?293 It seems very much more likely that he himself imagined the matter as nearly all his readers do.

But, in that case, what are we to say of this passage? I will answer first by explaining the way in which I understood it before I was aware that it had caused so much difficulty. I supposed that an interview had taken place after scene v., a scene which shows Macbeth shrinking, and in which his last words were 'we will speak further.' In this interview, I supposed, his wife had so wrought upon him that he had at last yielded and pledged himself by oath to do the murder. As for her statement that he had 'broken the enterprise' to her, I took it to refer to his letter to her,—a letter written when time and place did not adhere, for he did not yet know that Duncan was coming to visit him. In the letter he does not, of course, openly 'break the enterprise' to her, and it is not likely that he would do such a thing in a letter; but if they had had ambitious conversations, in which each felt that some half-formed guilty idea was floating in the mind of the other, she might naturally take the words of the letter as indicating much more than they said; and then in her passionate contempt at his hesitation, and her passionate eagerness to overcome it, she might easily accuse him, doubtless with exaggeration, and probably with conscious exaggeration, of having actually proposed the murder. And Macbeth, knowing that when he wrote the letter he really had been thinking of murder, and indifferent to anything except the question whether murder should be done, would easily let her statement pass unchallenged.