полная версия

полная версияThe Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence

Being bound for nearly the same point, the two hostile bodies steered parallel courses, each ignorant of the other's nearness. In the latitude of Bermuda both suffered from a violent gale, but the French most; the flagship Languedoc losing her main and mizzen topmasts. On the 25th of November one53 of Hotham's convoy fell into the hands of d'Estaing, who then first learned of the British sailing. Doubtful whether their destination was Barbados or Antigua,—their two chief stations,—he decided for the latter. Arriving off it on the 6th of December, he cruised for forty-eight hours, and then bore away for Fort Royal, Martinique, the principal French depot in the West Indies, where he anchored on the 9th. On the 10th Hotham joined Barrington at Barbados.

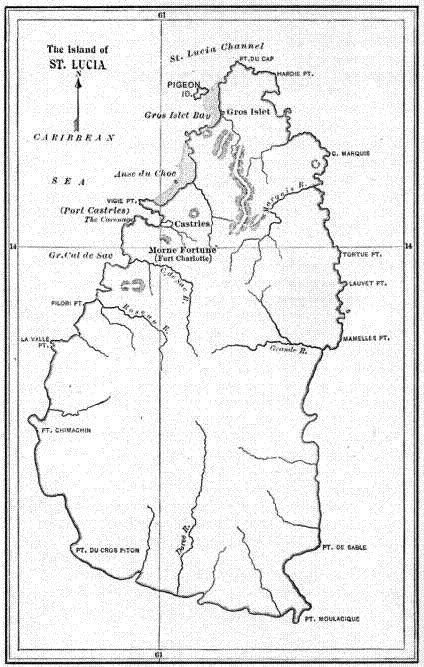

Barrington knew already what he wanted to do, and therefore lost not a moment in deliberation. The troops were kept on board, Hotham's convoy arrangements being left as they were. On the morning of December 12th the entire force sailed again, the main changes in it being in the chief command, and in the addition of Barrington's two ships of the line. On the afternoon of the 13th the shipping anchored in the Grand Cul de Sac, an inlet on the west side of Santa Lucia, which is seventy miles east-north-east from Barbados. Part of the troops landed at once, and seized the batteries and heights on the north side of the bay. The remainder were put on shore the next morning. The French forces were inadequate to defend their works; but it is to be observed that they were driven with unremitting energy, and that to this promptness the British owed their ability to hold the position.

Island of Santa Lucia

Three miles north of the Cul de Sac is a bay then called the Carénage; now Port Castries. At its northern extremity is a precipitous promontory, La Vigie, then fortified, upon the tenure of which depended not only control of that anchorage, but also access to the rear of the works which commanded the Cul de Sac. If those works fell, the British squadron must abandon its position and put to sea, where d'Estaing's much superior fleet would be in waiting. On the other hand, if the squadron were crushed at its anchors, the troops were isolated and must ultimately capitulate. Therefore La Vigie and the squadron were the two keys to the situation, and the loss of either would be decisive.

By the evening of the 14th the British held the shore line from La Vigie to the southern point of the Cul de Sac, as well as Morne Fortuné (Fort Charlotte), the capital of the island. The feeble French garrison retired to the interior, leaving its guns unspiked, and its ammunition and stores untouched,—another instance of the danger of works turning to one's own disadvantage. It was Barrington's purpose now to remove the transports to the Carénage, as a more commodious harbour, probably also better defended; but he was prevented by the arrival of d'Estaing that afternoon. "Just as all the important stations were secured, the French colours struck, and General Grant's headquarters established at the Governor's house, the Ariadne frigate came in sight with the signal abroad for the approach of an enemy."54 The French fleet was seen soon afterwards from the heights above the squadron.

The British had gained much so far by celerity, but they still spared no time to take breath. The night was passed by the soldiers in strengthening their positions, and by the Rear-Admiral in rectifying his order to meet the expected attack. The transports, between fifty and sixty in number, were moved inside the ships of war, and the latter were most carefully disposed across the mouth of the Cul de Sac bay. At the northern (windward)55 end was placed the Isis, 50, well under the point to prevent anything from passing round her; but for further security she was supported by three frigates, anchored abreast of the interval between her and the shore. From the Isis the line extended to the southward, inclining slightly outward; the Prince of Wales, 74, Barrington's flagship, taking the southern flank, as the most exposed position. Between her and the Isis were five other ships,—the Boyne, 70, Nonsuch, 64, St. Albans, 64, Preston, 50, and Centurion, 50. The works left by the French at the north and south points of the bay may have been used to support the flanks, but Barrington does not say so in his report.

D'Estaing had twelve ships of the line, and two days after this was able to land seven thousand troops. With such a superiority it is evident that the British would have been stopped in the midst of their operations, if he had arrived twenty-four hours sooner. To gain time, Barrington had sought to prevent intelligence reaching Fort Royal, less than fifty miles distant, by sending cruisers in advance of his squadron, to cover the approaches to Santa Lucia; but, despite his care, d'Estaing had the news on the 14th. He sailed at once, and, as has been said, was off Santa Lucia that evening. At daybreak of the 15th he stood in for the Carénage; but when he came within range, a lively cannonade told him that the enemy was already in possession. He decided therefore to attack the squadron in the Cul de Sac, and at 11.30 the French passed along it from north to south, firing, but without effect. A second attempt was made in the afternoon, directed upon the lee flank, but it was equally unavailing. The British had three men killed; the French loss is not given, but is said to have been slight. It is stated that that day the sea breeze did not penetrate far enough into the bay to admit closing. This frequently happens, but it does not alter the fact that the squadron was the proper point of attack, and that, especially in the winter season, an opportunity to close must offer soon. D'Estaing, governed probably by the soldierly bias he more than once betrayed, decided now to assault the works on shore. Anchoring in a small bay north of the Carénage, he landed seven thousand men, and on the 18th attempted to storm the British lines at La Vigie. The neck of land connecting the promontory with the island is very flat, and the French therefore labored under great disadvantage through the commanding position of their enemy. It was a repetition of Bunker Hill, and of many other ill-judged and precipitate frontal attacks. After three gallant but ineffectual charges, led by d'Estaing in person, the assailants retired, with the loss of forty-one officers and eight hundred rank and file, killed and wounded.

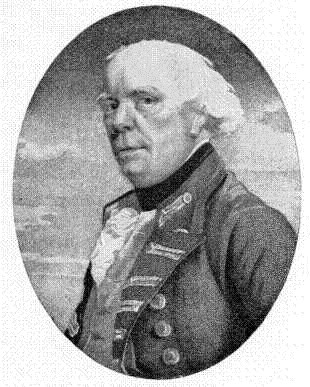

Admiral, the Honourable Samuel Barrington

D'Estaing reëmbarked his men, and stood ready again to attack Barrington; a frigate being stationed off the Cul de Sac, to give notice when the wind should serve. On the 24th she signalled, and the fleet weighed; but Barrington, who had taken a very great risk for an adequate object, took no unnecessary chances through presumption. He had employed his respite to warp the ships of war farther in, where the breeze reached less certainly, and where narrower waters gave better support to the flanks. He had strengthened the latter also by new works, in which he had placed heavy guns from the ships, manned by seamen. For these or other reasons d'Estaing did not attack. On the 29th he quitted the island, and on the 30th the French governor, the Chevalier de Micoud, formally capitulated.

This achievement of Barrington and of Major-General James Grant, who was associated with him, was greeted at the time with an applause which will be echoed by the military judgment of a later age. There is a particular pleasure in finding the willingness to incur a great risk, conjoined with a care that chances nothing against which the utmost diligence and skill can provide. The celerity, forethought, wariness, and daring of Admiral Barrington have inscribed upon the records of the British Navy a success the distinction of which should be measured, not by the largeness of the scale, but by the perfection of the workmanship, and by the energy of the execution in face of great odds.

Santa Lucia remained in the hands of the British throughout the war. It was an important acquisition, because at its north-west extremity was a good and defensible anchorage, Gros Ilet Bay, only thirty miles from Fort Royal in Martinique. In it the British fleet could lie, when desirable to close-watch the enemy, yet not be worried for the safety of the port when away; for it was but an outpost, not a base of operations, as Fort Royal was. It was thus used continually, and from it Rodney issued for his great victory in April, 1782.

During the first six months of 1779 no important incident occurred in the West Indies. On the 6th of January, Vice-Admiral Byron, with ten ships of the line from Narragansett Bay, reached Santa Lucia, and relieved Barrington of the chief command. Both the British and the French fleets were reinforced in the course of the spring, but the relative strength remained nearly as before, until the 27th of June, when the arrival of a division from Brest made the French numbers somewhat superior.

Shortly before this, Byron had been constrained by one of the commercial exigencies which constantly embarrassed the military action of British admirals. A large convoy of trading ships, bound to England, was collecting at St. Kitts, and he thought necessary to accompany it part of the homeward way, until well clear of the French West India cruisers. For this purpose he left Santa Lucia early in June. As soon as the coast was clear, d'Estaing, informed of Byron's object, sent a small combined expedition against St. Vincent, which was surrendered on the 18th of the month. On the 30th the French admiral himself quitted Fort Royal with his whole fleet,—twenty-five ships of the line and several frigates,—directing his course for the British Island of Grenada, before which he anchored on the 2d of July. With commendable promptitude, he landed his troops that evening, and on the 4th the island capitulated. Except as represented by one small armed sloop, which was taken, the British Navy had no part in this transaction. Thirty richly laden merchant ships were captured in the port.

At daybreak of July 6th, Byron appeared with twenty-one sail of the line, one frigate, and a convoy of twenty-eight vessels, carrying troops and equipments. He had returned to Santa Lucia on the 1st, and there had heard of the loss of St. Vincent, with a rumor that the French had gone against Grenada. He consequently had put to sea on the 3d, with the force mentioned.

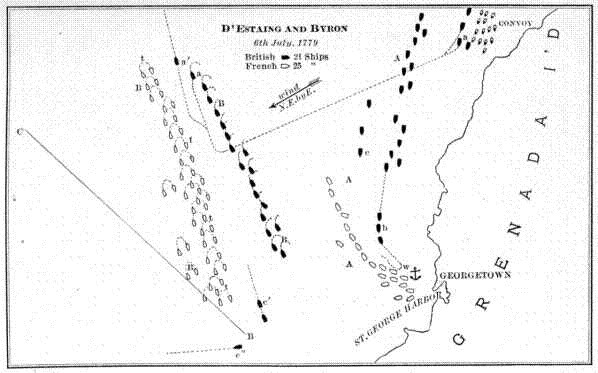

D'Estaing and Byron, July 6, 1779

The British approach was reported to d'Estaing during the night of July 5th. Most of his fleet was then lying at anchor off Georgetown, at the south-west of the island; some vessels, which had been under way on look-out duty, had fallen to leeward.56 At 4 A.M. the French began to lift their anchors, with orders to form line of battle on the starboard tack, in order of speed; that is, as rapidly as possible without regard to usual stations. When daylight had fully made, the British fleet (A) was seen standing down from the northward, close inshore, on the port tack, with the wind free at north-east by east. It was not in order, as is evident from the fact that the ships nearest the enemy, and therefore first to close, ought to have been in the rear on the then tack. For this condition there is no evident excuse; for a fleet having a convoy necessarily proceeds so slowly that the war-ships can keep reasonable order for mutual support. Moreover, irregularities that are permissible in case of emergency, or when no enemy can be encountered suddenly, cease to be so when the imminent probability of a meeting exists. The worst results of the day are to be attributed to this fault. Being short of frigates, Byron had assigned three ships of the line (a), under Rear-Admiral Rowley, to the convoy, which of course was on the off hand from the enemy, and somewhat in the rear. It was understood, however, that these would be called into the line, if needed.

When the French (AA) were first perceived by Byron, their line was forming; the long thin column lengthening out gradually to the north-north-west, from the confused cluster57 still to be seen at the anchorage. Hoping to profit by their disorder, he signalled "a general chase in that quarter,58 as well as for Rear-Admiral Rowley to leave the convoy; and as not more than fourteen or fifteen of the enemy's ships appeared to be in line, the signal was made for the ships to engage, and form as they could get up."59 It is clear from this not only that the ships were not in order, but also that they were to form under fire. Three ships, the Sultan, 74, the Prince of Wales, 74, and the Boyne, 70, in the order named,—the second carrying Barrington's flag,—were well ahead of the fleet (b). The direction prescribed for the attack, that of the clustered ships in the French rear, carried the British down on a south-south-west, or south by west, course; and as the enemy's van and centre were drawing out to the north-north-west, the two lines at that time resembled the legs of a "V," the point of which was the anchorage off Georgetown. Barrington's three ships therefore neared the French order gradually, and had to receive its fire for some time before they could reply, unless, by hauling to the wind, they diverged from the set course. This, and their isolation, made their loss very heavy. When they reached the rear of the French, the latter's column was tolerably formed, and Barrington's ships wore (w) in succession,—just as Harland's had done in Keppel's action,—to follow on the other tack. In doing this, the Sultan kept away under the stern of the enemy's rearmost ship, to rake her; to avoid which the latter bore up. The Sultan thus lost time and ground, and Barrington took the lead, standing along the French line, from rear to van, and to windward.

Meanwhile, the forming of the enemy had revealed to Byron for the first time, and to his dismay, that he had been deceived in thinking the French force inferior to his own. "However, the general chase was continued, and the signal made for close engagement."60 The remainder of the ships stood down on the port tack, as the first three had done, and wore in the wake of the latter, whom they followed; but before reaching the point of wearing, three ships, "the Grafton, 74, the Cornwall, 74, and the Lion, 64 (c), happening to be to leeward,61 sustained the fire of the enemy's whole line, as it passed on the starboard tack." It seems clear that, having had the wind, during the night and now, and being in search of an enemy, it should not have "happened" that any ships should have been so far to leeward as to be unsupported. Captain Thomas White, R.N., writing as an advocate of Byron, says,62 "while the van was wearing … the sternmost ships were coming up under Rear-Admiral Hyde Parker.... Among these ships, the Cornwall and Lion, from being nearer the enemy than those about them (for the rear division had not then formed into line), drew upon themselves almost the whole of the enemy's fire." No words can show more clearly the disastrous, precipitate disorder in which this attack was conducted. The Grafton, White says, was similarly situated. In consequence, these three were so crippled, besides a heavy loss in men, that they dropped far to leeward and astern (c', c"), when on the other tack.

When the British ships in general had got round, and were in line ahead on the starboard tack,—the same as the French,—ranging from rear to van of the enemy (Positions B, B, B), Byron signalled for the eight leading ships to close together, for mutual support, and to engage close. This, which should have been done—not with finikin precision, but with military adequacy—before engaging, was less easy now, in the din of battle and with crippled ships. A quick-eyed subordinate, however, did something to remedy the error of his chief. Rear-Admiral Rowley was still considerably astern, having to make up the distance between the convoy and the fleet. As he followed the latter, he saw Barrington's three ships unduly separated and doubtless visibly much mauled. Instead, therefore, of blindly following his leader, he cut straight across (aa) to the head of the column to support the van,—an act almost absolutely identical with that which won Nelson renown at Cape St. Vincent. In this he was followed by the Monmouth, 64, the brilliancy of whose bearing was so conspicuous to the two fleets that it is said the French officers after the battle toasted "the little black ship." She and the Suffolk, 74, Rowley's flagship, also suffered severely in this gallant feat.

It was imperative with Byron now to keep his van well up with the enemy, lest he should uncover the convoy, broad on the weather bow of the two fleets. "They seemed much inclined to cut off the convoy, and had it much in their power by means of their large frigates, independent of ships of the line."63 On the other hand, the Cornwall, Grafton, and Lion, though they got their heads round, could not keep up with the fleet (c', c"), and were dropping also to leeward—towards the enemy. At noon, or soon after, d'Estaing bore up with the body of his force to join some of his vessels that had fallen to leeward. Byron very properly—under his conditions of inferiority—kept his wind; and the separation of the two fleets, thus produced, caused firing to cease at 1 P.M.

The enemies were now ranged on parallel lines, some distance apart; still on the starboard tack, heading north-north west. Between the two, but far astern, the Cornwall, Grafton, Lion, and a fourth British ship, the Fame, were toiling along, greatly crippled. At 3 P.M., the French, now in good order, tacked together (t, t, t), which caused them to head towards these disabled vessels. Byron at once imitated the movement, and the eyes of all in the two fleets anxiously watched the result. Captain Cornwallis of the Lion, measuring the situation accurately, saw that, if he continued ahead, he would be in the midst of the French by the time he got abreast of them. Having only his foremast standing, he put his helm up, and stood broad off before the wind (c"), across the enemy's bows, for Jamaica. He was not pursued. The other three, unable to tack and afraid to wear, which would put them also in the enemy's power, stood on, passed to windward of the latter, receiving several broadsides, and so escaped to the northward. The Monmouth was equally maltreated; in fact, she had not been able to tack to the southward with the fleet. Continuing north (a'), she became now much separated. D'Estaing afterwards reestablished his order of battle on the port tack, forming upon the then leewardmost ship, on the line BC.

Byron's action off Grenada, viewed as an isolated event, was the most disastrous in results that the British Navy had fought since Beachy Head, in 1690. That the Cornwall, Grafton, and Lion were not captured was due simply to the strained and inept caution of the French admiral. This Byron virtually admitted. "To my great surprise no ship of the enemy was detached after the Lion. The Grafton and Cornwall might have been weathered by the French, if they had kept their wind,… but they persevered so strictly in declining every chance of close action that they contented themselves with firing upon these ships when passing barely within gunshot, and suffered them to rejoin the squadron, without one effort to cut them off." Suffren,64 who led the French on the starboard tack, and whose ship, the Fantasque, 64, lost 22 killed and 43 wounded, wrote: "Had our admiral's seamanship equalled his courage, we would not have allowed four dismasted ships to escape." That the Monmouth and Fame could also have been secured is extremely probable; and if Byron, in order to save them, had borne down to renew the action, the disaster might have become a catastrophe.

That nothing resulted to the French from their great advantage is therefore to be ascribed to the incapacity of their Commander-in-Chief. It is instructive to note also the causes of the grave calamity which befell the British, when twenty-one ships met twenty-four,65—a sensible but not overwhelming superiority. These facts have been shown sufficiently. Byron's disaster was due to attacking with needless precipitation, and in needless disorder. He had the weather-gage, it was early morning, and the northeast trade-wind, already a working breeze, must freshen as the day advanced. The French were tied to their new conquest, which they could not abandon without humiliation; not to speak of their troops ashore. Even had they wished to retreat, they could not have done so before a general chase, unless prepared to sacrifice their slower ships. If twenty-four ships could reconcile themselves to running from twenty-one, it was scarcely possible but that the fastest of these would overtake the slowest of those. There was time for fighting, an opportunity for forcing action which could not be evaded, and time also for the British to form in reasonably good order.

It is important to consider this, because, while Keppel must be approved for attacking in partial disorder, Byron must be blamed for attacking in utter disorder. Keppel had to snatch opportunity from an unwilling foe. Having himself the lee-gage, he could not pick and choose, nor yet manœuvre; yet he brought his fleet into action, giving mutual support throughout nearly, if not quite, the whole line. What Byron did has been set forth; the sting is that his bungling tactics can find no extenuation in any urgency of the case.

The loss of the two fleets, as given by the authorities of either nation, were: British, 183 killed, 346 wounded; French, 190 killed, 759 wounded. Of the British total, 126 killed and 235 wounded, or two thirds, fell to the two groups of three ships each, which by Byron's mismanagement were successively exposed to be cut up in detail by the concentrated fire of the enemy. The British loss in spars and sails—in motive-power—also exceeded greatly that of the French.

After the action d'Estaing returned quietly to Grenada. Byron went to St. Kitts to refit; but repairs were most difficult, owing to the dearth of stores in which the Admiralty had left the West Indies. With all the skill of the seamen of that day in making good damages, the ships remained long unserviceable, causing great apprehension for the other islands. This state of things d'Estaing left unimproved, as he had his advantage in the battle. He did, indeed, parade his superior force before Byron's fleet as it lay at anchor; but, beyond the humiliation naturally felt by a Navy which prided itself on ruling the sea, no further injury was done.

In August Byron sailed for England. Barrington had already gone home, wounded. The station therefore was left in command of Rear-Admiral Hyde Parker,66 and so remained until March, 1780, when the celebrated Rodney arrived as Commander-in-Chief on the Leeward Islands Station. The North American Station was given to Vice-Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot, who had under him a half-dozen ships of the line, with headquarters at New York. His command was ordinarily independent of Rodney's, but the latter had no hesitation in going to New York on emergency and taking charge there; in doing which he had the approval of the Admiralty.

The approach of winter in 1778 had determined the cessation of operations, both naval and military, in the northern part of the American continent, and had led to the transfer of five thousand troops to the West Indies, already noted. At the same time, an unjustifiable extension of British effort, having regard to the disposable means, was undertaken in the southern States of Georgia and South Carolina. On the 27th of November a small detachment of troops under Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Campbell, sailed from Sandy Hook, convoyed by a division of frigates commanded by Captain Hyde Parker.67 The expedition entered the Savannah River four weeks later, and soon afterwards occupied the city of the same name. Simultaneously with this, by Clinton's orders, General Prevost moved from Florida, then a British colony, with all the men he could spare from the defence of St. Augustine. Upon his arrival in Savannah he took command of the whole force thus assembled.