полная версия

полная версияThe Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence

D'Orvilliers and Keppel, off Ushant, July 27, 1778

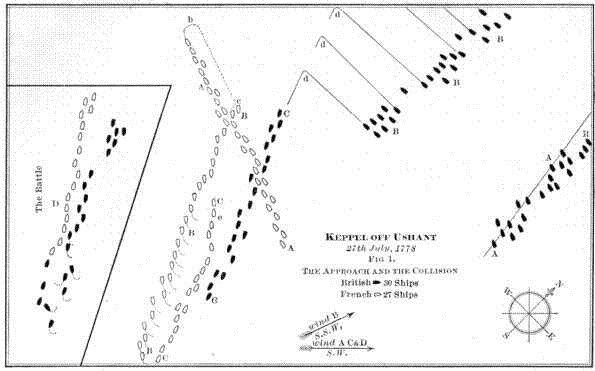

Figure 1

Keppel so far had made no signal for the line of battle, nor did he now. Recognising from the four days' chase that his enemy was avoiding action, he judged correctly that he should force it, even at some risk. It was not the time for a drill-master, nor a parade. Besides, thanks to the morning signal for the leewardly ships to chase, these, forming the rear of the disorderly column in which he was advancing, were now well to windward, able therefore to support their comrades, if needful, as well as to attack the enemy. In short, practically the whole force was coming into action, although much less regularly than might have been desired. What was to follow was a rough-and-ready fight, but it was all that could be had, and better than nothing. Keppel therefore simply made the signal for battle, and that just as the firing began. The collision was so sudden that the ships at first had not their colours flying.

The French also, although their manœuvres had been more methodical, were in some confusion. It is not given to a body of thirty ships, of varying qualities, to attain perfection of movement in a fortnight of sea practice. The change of wind had precipitated an action, which one admiral had been seeking, and the other shunning; but each had to meet it with such shift as he could. The British (CC) being close-hauled, the French (CC), advancing on a parallel line, were four points44 off the wind. Most of their ships, therefore, could have gone clear to windward of their opponents, but the fact that the latter could reach some of the leaders compelled the others to support them. As d'Orvilliers had said, it was hard to avoid an enemy resolute to fight. The leading three French vessels45 (e) hauled their wind, in obedience to the admiral's signal to form the line of battle, which means a close-hauled line. The effect of this was to draw them gradually away from the hostile line, taking them out of range of the British centre and rear. This, if imitated by their followers, would render the affair even more partial and indecisive than such passing by usually was. The fourth French ship began the action, opening fire soon after eleven. The vessels of the opposing fleets surged by under short canvas, (D), firing as opportunity offered, but necessarily much handicapped by smoke, which prevented the clear sight of an enemy, and caused anxiety lest an unseen friend might receive a broadside. "The distance between the Formidable, 90, (Palliser's flagship) and the Egmont, 74, was so short," testified Captain John Laforey, whose three-decker, the Ocean, 90, was abreast and outside this interval, "that it was with difficulty I could keep betwixt them to engage, without firing upon them, and I was once very near on board the Egmont,"—next ahead of the Ocean. The Formidable kept her mizzen topsail aback much of the time, to deaden her way, to make the needed room ahead for the Ocean, and also to allow the rear ships to close. "At a quarter past one," testified Captain Maitland of the Elizabeth, 74, "we were very close behind the Formidable, and a midshipman upon the poop called out that there was a ship coming on board on the weatherbow. I put the helm up,… and found, when the smoke cleared away, I was shot up under the Formidable's lee. She was then engaged with the two last ships in the French fleet, and, as I could not fire at them without firing through the Formidable, I was obliged to shoot on."46 Captain Bazely, of the Formidable, says of the same incident, "The Formidable did at the time of action bear up to one of the enemy's ships, to avoid being aboard of her, whose jib boom nearly touched the main topsail weather leech of the Formidable. I thought we could not avoid being on board."

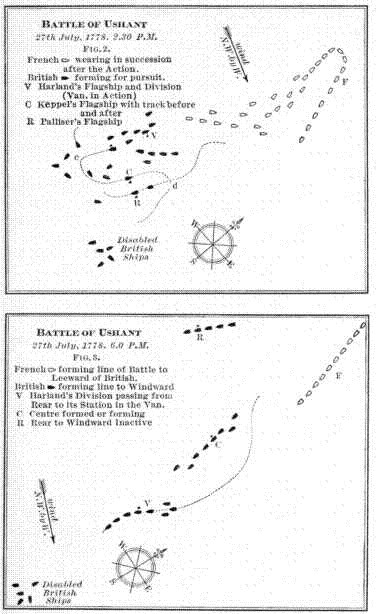

Contrary to the usual result, the loss of the rear division, in killed and wounded, was heaviest, nearly equalling the aggregate of the two others.47 This was due to the morning signal to chase to windward, which brought these ships closer than their leaders. As soon as the British van, ten ships, had passed the French rear, its commander, Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Harland, anticipating Keppel's wishes, signalled it to go about and follow the enemy (Fig. 2, V). As the French column was running free, these ships, when about, fetched to windward of its wake. When the Victory drew out of the fire, at 1 P.M., Keppel also made a similar signal, and attempted to wear (c), the injuries to his rigging not permitting tacking; but caution was needed in manœuvring across the bows of the following ships, and it was not till 2 P.M., that the Victory was about on the other tack (Fig. 2, C), heading after the French. At this time, 2 P.M., just before or just after wearing, the signal for battle was hauled down, and that for the line of battle was hoisted. The object of the latter was to re-form the order, and the first was discontinued, partly because no longer needed, chiefly that it might not seem to contradict the urgent call for a re-formation.

At this time six or seven of Harland's division were on the weather bow of the Victory, to windward (westward), but a little ahead, and standing like her after the French; all on the port tack (Fig. 2). None of the centre division succeeded in joining the flagship at once. At 2.30 Palliser's ship, the Formidable (R), on the starboard tack, passed the Victory to leeward, apparently the last of the fleet out of action. A half-hour after this the Victory had been joined by three of the centre, which were following her in close order, the van remaining in the same relative position. Astern of these two groups from van and centre were a number of other ships in various degrees of confusion,—some going about, some trying to come up, others completely disabled. Especially, there was in the south-south-east, therefore well to leeward, a cluster of four or five British vessels, evidently temporarily incapable of manœuvring.

This was the situation which met the eye of the French admiral, scanning the field as the smoke drove away. The disorder of the British, which originated in the general chase, had increased through the hurry of the manœuvres succeeding the squall, and culminated in the conditions just described. It was an inevitable result of a military exigency confronted by a fleet only recently equipped. The French, starting from a better formation, had come out in better shape. But, after all, it seems difficult wholly to remedy the disadvantage of a policy essentially defensive; and d'Orvilliers' next order, though well conceived, was resultless. At 1 P.M.48 he signalled his fleet to wear in succession, and form the line of battle on the starboard tack (Fig. 2, F). This signal was not seen by the leading ship, which should have begun the movement. The junior French admiral, in the fourth ship from the van, at length went about, and spoke the flagship, to know what was the Commander-in-Chief's desire. D'Orvilliers explained that he wished to pass along the enemy's fleet from end to end, to leeward, because in its disordered state there was a fair promise of advantage, and by going to leeward—presenting his weather side to the enemy—he could use the weather lower-deck guns, whereas, in the then state of the sea, the lee lower ports could not be opened. Thus explained, the movement was executed, but the favourable moment had passed. It was not till 2.30 that the manœuvre was evident to the British.

D'Orvilliers and Keppel, off Ushant, July 27, 1778

Figures 2 and 3

As soon as Keppel recognised his opponent's intention, he wore the Victory again, (d), a few minutes after 3 P.M., and stood slowly down, on the starboard tack off the wind, towards his crippled ships in the south-south-east, keeping aloft the signal for the line of battle, which commanded every manageable ship to get to her station (Fig. 3, C). As this deliberate movement was away from the enemy, (F), Palliser tried afterwards to fix upon it the stigma of flight,—a preposterous extravagancy. Harland put his division about at once and joined the Admiral. On this tack his station was ahead of the Victory, but in consequence of a message from Keppel he fell in behind her, to cover the rear until Palliser's division could repair damage and take their places. At 4 P.M. Harland's division was in the line. Palliser's ships, as they completed refitting, ranged themselves before or behind his flagship; their captains considering, as they testified, that they took station from their divisional commander, and not from the ship of the Commander-in-Chief. There was formed thus, on the weather quarter of the Victory, and a mile or two distant, a separate line of ships, constituting on this tack the proper rear of the fleet, and dependent for initiative on Palliser's flagship (Fig. 3, R). At 5 P.M. Keppel sent word by a frigate to Palliser to hasten into the line, as he was only waiting for him to renew the action, the French now having completed their manœuvre. They had not attacked, as they might have done, but had drawn up under the lee of the British, their van abreast the latter's centre. At the same time Harland was directed to move to his proper position in the van, which he at once did (Fig. 3, V). Palliser made no movement, and Keppel with extraordinary—if not culpable—forbearance refrained from summoning the rear ships into line by their individual pennants. This he at last did about 7 P.M., signalling specifically to each of the vessels then grouped with Palliser, (except his own flagship), to leave the latter and take their posts in the line. This was accordingly done, but it was thought then to be too late to renew the action. At daylight the next morning, only three French ships were in sight from the decks; but the main body could be seen in the south-east from some of the mastheads, and was thought to be from fifteen to twenty miles distant.

Though absolutely indecisive, this was a pretty smart skirmish; the British loss being 133 killed and 373 wounded, that of the French 161 killed and 513 wounded. The general result would appear to indicate that the French, in accordance with their usual policy, had fired to cripple their enemy's spars and rigging, the motive-power. This would be consistent with d'Orvilliers' avowed purpose of avoiding action except under favourable circumstances. As the smoke thickened and confusion increased, the fleets had got closer together, and, whatever the intention, many shot found their way to the British hulls. Nevertheless, as the returns show, the number of men hit among the French was to the British nearly as 7 to 5. On the other hand, it is certain that the manœuvring power of the French after the action was greater than that of the British.

Both sides claimed the advantage. This was simply a point of honour, or of credit, for material advantage accrued to neither. Keppel had succeeded in forcing d'Orvilliers to action against his will; d'Orvilliers, by a well-judged evolution, had retained a superiority of manœuvring power after the engagement. Had his next signal been promptly obeyed, he might have passed again by the British fleet, in fairly good order, before it re-formed, and concentrated his fire on the more leewardly of its vessels. Even under the delay, it was distinctly in his power to renew the fight; and that he did not do so forfeits all claim to victory. Not to speak of the better condition of the French ships, Keppel, by running off the wind, had given his opponent full opportunity to reach his fleet and to attack. Instead of so doing, d'Orvilliers drew up under the British lee, out of range, and offered battle; a gallant defiance, but to a crippled foe.

Time was thus given to the British to refit their ships sufficiently to bear down again. This the French admiral should not have permitted. He should have attacked promptly, or else have retreated; to windward, or to leeward, as seemed most expedient. Under the conditions, it was not good generalship to give the enemy time, and to await his pleasure. Keppel, on the other hand, being granted this chance, should have renewed the fight; and here arose the controversy which set all England by the ears, and may be said to have immortalised this otherwise trivial incident. Palliser's division was to windward from 4 to 7 P.M., while the signals were flying to form line of battle, and to bear down in the Admiral's wake; and Keppel alleged that, had these been obeyed by 6 P.M., he would have renewed the battle, having still over two hours of daylight. It has been stated already that, besides the signals, a frigate brought Palliser word that the Admiral was waiting only for him.

The immediate dispute is of slight present interest, except as an historical link in the fighting development of the British Navy; and only this historical significance justifies more than a passing mention. In 1778 men's minds were still full of Byng's execution in 1757, and of the Mathews and Lestock affair in 1744, which had materially influenced Byng in his action off Minorca. Keppel repeatedly spoke of himself as on trial for his life; and he had been a member of Byng's court-martial. The gist of the charges against him, preferred by Palliser, was that he attacked in the first instance without properly forming his line, for which Mathews had been censured; and, secondly, that by not renewing the action after the first pass-by, and by wearing away from the French fleet, he had not done his utmost to "take, sink, burn, and destroy." This had been the charge on which Byng was shot. Keppel, besides his justifying reasons for his course in general, alleged and proved his full intention to attack again, had not Palliser failed to come into line, a delinquency the same as that of Lestock, which contributed to Mathew's ruin.

In other words, men's minds were breaking away from, but had not thrown off completely, the tyranny of the Order of Battle,—one of the worst of tyrannies, because founded on truth. Absolute error, like a whole lie, is open to speedy detection; half-truths are troublesome. The Order of Battle49 was an admirable servant and a most objectionable despot. Mathews, in despair over a recalcitrant second, cast off the yoke, engaged with part of his force, was ill supported and censured; Lestock escaping. Byng, considering this, and being a pedant by nature, would not break his line; the enemy slipped away, Minorca surrendered, and he was shot. In Keppel's court-martial, twenty-eight out of the thirty captains who had been in the line were summoned as witnesses. Most of them swore that if Keppel had chased in line of battle that day, there could have been no action, and the majority of them cordially approved his course; but there was evidently an undercurrent still of dissent, and especially in the rear ships, where there had been some of the straggling inevitable in such movements. Their commanders therefore had uncomfortable experience of the lack of mutual support, which the line of battle was meant to insure.

Another indication of still surviving pedantry was the obligation felt in the rear ships to take post about their own admiral, and to remain there when the signals for the line of battle, and to bear down in the admiral's wake, were flying. Thus Palliser's own inaction, to whatever cause due, paralysed the six or eight sail with him; but it appears to the writer that Keppel was seriously remiss in not summoning those ships by their own pennants, as soon as he began to distrust the purposes of the Vice-Admiral, instead of delaying doing so till 7 P.M., as he did. It is a curious picture presented to us by the evidence. The Commander-in-Chief, with his staff and the captain of the ship, fretting and fuming on the Victory's quarter-deck; the signals flying which have been mentioned; Harland's division getting into line ahead; and four points on the weather quarter, only two miles distant, so that "every gun and port could be counted," a group of seven or eight sail, among them the flag of the third in command, apparently indifferent spectators. The Formidable's only sign of disability was the foretopsail unbent for four hours,—a delay which, being unexplained, rather increased than relieved suspicion, rife then throughout the Navy. Palliser was a Tory, and had left the Board of Admiralty to take his command. Keppel was so strong a Whig that he would not serve against the Americans; and he evidently feared that he was to be betrayed to his ruin.

Palliser's defence rested upon three principal points: (1), that the signal for the line of battle was not seen on board the Formidable; (2), that the signal to get into the Admiral's wake was repeated by himself; (3), that his foremast was wounded, and, moreover, found to be in such bad condition that he feared to carry sail on it. As regards the first, the signal was seen on board the Ocean, next astern of and "not far from"50 the Formidable; for the second, the Admiral should have been informed of a disability by which a single ship was neutralizing a division. The frigate that brought Keppel's message could have carried back this. Thirdly, the most damaging feature to Palliser's case was that he asserted that, after coming out from under fire, he wore at once towards the enemy; afterwards he wore back again. A ship that thus wore twice before three o'clock, might have displayed zeal and efficiency enough to run two miles, off the wind,51 at five, to support a fight. Deliberate treachery is impossible. To this writer the Vice-Admiral's behaviour seems that of a man in a sulk, who will do only that which he can find no excuses for neglecting. In such cases of sailing close, men generally slip over the line into grievous wrong.

Keppel was cleared of all the charges preferred against him; the accuser had not thought best to embody among them the delay to recall the ships which his own example was detaining. Against Palliser no specific charge was preferred, but the Admiralty directed a general inquiry into his course on the 27th of July. The court found his conduct "in many instances highly exemplary and meritorious,"—he had fought well,—"but reprehensible in not having acquainted the Commander-in-Chief of his distress, which he might have done either by the Fox, or other means which he had in his power." Public opinion running strongly for Keppel, his acquittal was celebrated with bonfires and illuminations in London; the mob got drunk, smashed the windows of Palliser's friends, wrecked Palliser's own house, and came near to killing Palliser himself. The Admiralty, in 1780, made him Governor of Greenwich Hospital.

On the 28th of July, the British and French being no longer in sight of each other, Keppel, considering his fleet too injured aloft to cruise near the French coast, kept away for Plymouth, where he arrived on the 31st. Before putting to sea again, he provided against a recurrence of the misdemeanor of the 27th by a general order, that "in future the Line is always to be taken from the Centre." Had this been in force before, Palliser's captains would have taken station by the Commander-in-Chief, and the Formidable would have been left to windward by herself. At the same time Howe was closing his squadron upon the centre in America; and Rodney, two years later, experienced the ill-effects of distance taken from the next ahead, when the leading ship of a fleet disregarded an order.

Although privately censuring Palliser's conduct, the Commander-in-Chief made no official complaint, and it was not until the matter got into the papers, through the talk of the fleet, that the difficulty began which resulted in the trial of both officers, early in the following year. After this, Keppel, being dissatisfied with the Admiralty's treatment, intimated his wish to give up the command. The order to strike his flag was dated March 18th, 1779. He was not employed afloat again, but upon the change of administration in 1782 he became First Lord of the Admiralty, and so remained, with a brief intermission, until December, 1783.

It is perhaps necessary to mention that both British and French asserted, and assert to this day, that the other party abandoned the field.52 The point is too trivial, in the author's opinion, to warrant further discussion of an episode the historical interest of which is very slight, though its professional lessons are valuable. The British case had the advantage—through the courts-martial—of the sworn testimony of twenty to thirty captains, who agreed that the British kept on the same tack under short sail throughout the night, and that in the morning only three French ships were visible. As far as known to the author, the French contention rests only on the usual reports.

CHAPTER VI

OPERATIONS IN THE WEST INDIES, 1778-1779. THE BRITISH INVASION OF GEORGIA AND SOUTH CAROLINA

Conditions of season exerted great influence upon the time and place of hostilities during the maritime war of 1778; the opening scenes of which, in Europe and in North America, have just been narrated. In European seas it was realised that naval enterprises by fleets, requiring evolutions by masses of large vessels, were possible only in summer. Winter gales scattered ships, impeded manœuvres, and made gun-fire ineffective. The same consideration prevailed to limit activity in North American waters to the summer; and complementary to this was the fact that in the West Indies hurricanes of excessive violence occurred from July to October. The practice therefore was to transfer effort from one quarter to the other in the Western Hemisphere, according to the season.

In the recent treaty with the United States, the King of France had formally renounced all claim to acquire for himself any part of the American continent then in possession of Great Britain. On the other hand, he had reserved the express right to conquer any of her islands south of Bermuda. The West Indies were then the richest commercial region on the globe in the value of their products; and France wished not only to increase her already large possessions there, but also to establish more solidly her political and military tenure.

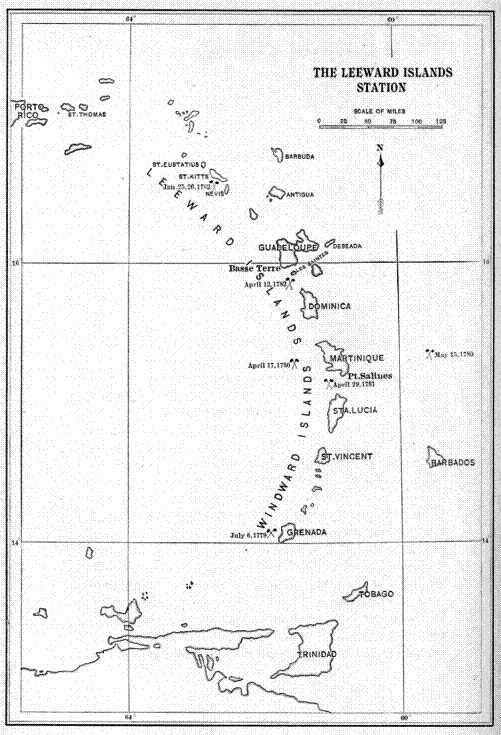

Leeward Islands (West Indies) Station

In September, 1778, the British Island of Dominica was seized by an expedition from the adjacent French colony of Martinique. The affair was a surprise, and possesses no special military interest; but it is instructive to observe that Great Britain was unprepared, in the West Indies as elsewhere, when the war began. A change had been made shortly before in the command of the Leeward Islands Station, as it was called, which extended from Antigua southward over the Lesser Antilles with headquarters at Barbados. Rear-Admiral the Hon. Samuel Barrington, the new-comer, leaving home before war had been declared, had orders not to quit Barbados till further instructions should arrive. These had not reached him when he learned of the loss of Dominica. The French had received their orders on the 17th of August. The blow was intrinsically somewhat serious, so far as the mere capture of a position can be, because the fortifications were strong, though they had been inadequately garrisoned. It is a mistake to build works and not man them, for their fall transfers to the enemy strength which he otherwise would need time to create. To the French the conquest was useful beyond its commercial value, because it closed a gap in their possessions. They now held four consecutive islands, from north to south, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, and Santa Lucia.

Barrington had two ships of the line: his flagship, the Prince of Wales, 74, and the Boyne, 70. If he had been cruising, these would probably have deterred the French. Upon receiving the news he put to sea, going as far as Antigua; but he did not venture to stay away because his expected instructions had not come yet, and, like Keppel, he feared an ungenerous construction of his actions. He therefore remained in Barbados, patiently watching for an opportunity to act.

The departure of Howe and the approach of winter determined the transference of British troops and ships from the continent to the Leeward Islands. Reinforcements had given the British fleet in America a numerical superiority, which for the time imposed a check upon d'Estaing; but Byron, proverbially unlucky in weather, was driven crippled to Newport, leaving the French free to quit Boston. The difficulty of provisioning so large a force as twelve ships of the line at first threatened to prevent the withdrawal, supplies being then extremely scarce in the port; but at the critical moment American privateers brought in large numbers of prizes, laden with provisions from Europe for the British army. Thus d'Estaing was enabled to sail for Martinique on the 4th of November. On the same day there left New York for Barbados a British squadron,—two 64's, three 50's, and three smaller craft,—under the command of Commodore William Hotham, convoying five thousand troops for service in the West Indies.