Полная версия

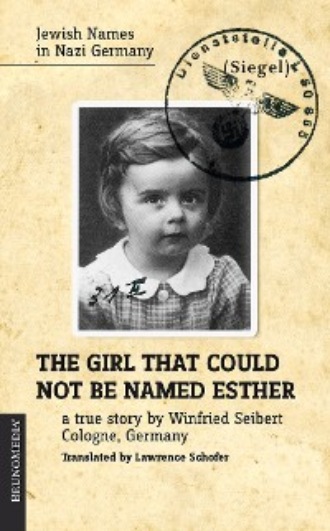

The girl that could not be named Esther

Wlochatz points to another change in the second edition of the family record book. On the basis of comments from linguists, names long established and familiar to the reader are listed in the Foreign Names section, names like Anna, Johanna, Maria, Paul, Peter, Johannes, Michel, Sepp, and others, which clearly have been seamlessly integrated into the German People for over a thousand years. A registry office, however, he continues in a conciliatory tone, must take into consideration not only the wishes of the German experts, but also the events of everyday life. He goes on:

And so established biblical names should be retained, even though most of them come from the Hebrew; otherwise, we would have to logically exclude names like those mentioned above. Where would all this lead us?41› Reference

That sounds compassionate and reasonable – Wlochatz wanted to retain established biblical names. A decade later, in 1931, Wlochatz turned his attention to swings of the people’s spirit in the giving of names (in an article in the Journal of Registry Office Affairs). He names four major trends, with the primary one being consciously and decidedly German names. 42› Reference

He distinguishes three sub-trends which all have in common that their motivating spirit absolutely demands that German children be given good German names.

In these sub-divisions of the consciously German trend, Wlochatz includes the Nordic movement, and especially the Folkish movement, referring to an unspecified Germanic element of the Volk — Folk, the People — a movement increasingly identified with Nazi ideology or at least recognized as its forerunner. He naively calls this a part of ethical cultural longings.

In Germany the religious beliefs of our pre-Christian ancestors are fostered and spread in the rapidly growing ‘Nordic Community of Faith,’ which aspires to the spiritual rebirth of the ‚Germanic’ man. In these circles children receive ancient Teutonic names. This spiritual attitude often overlaps with the other trend, the more recent ‘Folkish’ movement, which is much larger and more significant in its effects on the life of our people. Here, we are naturally not interested in this movement as a political party, but rather only in its effect within the sphere of German ethical cultural aspirations. And it is here that we find a decided rejection of all foreign influences, especially Semitic ones, and a move toward the goal of racial purification of the German people. As a result, within this movement we meet only pure Germanic names, even from time to time in ancient Teutonic form. Of course, it should be observed that through the ‘Folkish’ movement a large number of old German words have been brought back to life as well.

The religious Christian trend delineated by Wlochatz — seen among our nation’s Catholic brethren, who are unquestionably of good German orientation — is accustomed to many foreign names, including, since they are taken from the Bible, many of Hebrew origin. Wlochatz takes a critical view of this:

Since the religious writings of the Hebrews, that is, the Israelites, have found a home in the Christian world as well, and since their children are familiar with the great personalities of the Jewish people through Bible instruction, it should not be surprising that there are still a number of Germans who in the choice of names for their children reach into the treasury of a people foreign to us. Quite frequently this occurs as the expression of personal piety.

The registry office director, now at ease in retirement, clearly has made progress. He declares himself at one with the consciously German point of view, which calls for racial purification, that is, an inner rebirth of the Germans. 43› Reference This stance has made the naming question a question of conscience, driven by an imperious, demanding spirit. From Wlochatz’ point of view, the partisans of this route feel responsible for the coming generation. They are conscious of challenges to existence that remain completely foreign to the others. It thus follows that:

The call to give German names to German children became a demand, since it has been recognized that the German child undoubtedly has a right to a good German given name, and that German parents have the duty to start their children out in life equipped with such names... It can happen that the custom of pious Christian German parents to give a child a biblical name, and thus a sort of Hebrew name, may later lead to conflicts between child and parents. After all, the religious orientation of parents cannot be definitely assumed to be the orientation of the children, and certainly not when later in life the children learn to think differently about matters of faith.

For the first time, the viewpoint of the child’s welfare is sounded, an approach that could serve several purposes and one which we will meet in the Supreme Court. You can’t help being impressed by the certainty with which the ideology of the future was foretold. The thousand-year Reich was well established in the minds of many even before the thousand years had begun.

After these rather ponderous meditations by a retired registrar — to be sure, one with considerable influence on the activities of the registry office — the Berlin district court judge Dr. Boschan, also a longtime contributor to the Journal of Registry Office Affairs, took up the legal question. In mid-1936 he demanded a German-oriented giving of names, and inveighed against the danger of the German essence being infiltrated by foreign elements and the practice of half-hearted naming of children. 44› Reference He wrote:

According to the principles of the National Socialist state, which wants to create a true German homeland for its citizens, there must be a limit to the choice of foreign given names since the choice of foreign names is a purely capricious act. Legitimate grounds for the choice of a foreign name have not been demonstrated.

In today’s Germany we must establish the following principle: German children receive German names; foreign children receive foreign names. If legitimate grounds are given, exceptions may be allowed.45› Reference

This statement did not go unchallenged. Another Berlin state court judge commented briefly on Judge Boschan’s principle with these words:

These remarks may be relevant for future legislation. They should not be taken as the statement of current law; they certainly are not conceived as such.46› Reference

True, there was no legislation, but there was at any rate a directive from the Minister of the Interior on April 14, 1937, regarding the use of German given names.47› Reference It was not published in any official ministerial journal but rather in the Journal of Registry Office Affairs. Despite its questionable status as an official regulation, it played a great role in future decisions. Here is the text in full:

Children of Germans should basically receive only German names. However, not all Nordic names can be included as German names; insofar as concerns non-German names (e. g., Bjoern, Knut, Sven, Ragnhild, etc.), they are no more desirable than are other non-German names. On the other hand, names have been used in Germany for centuries that are originally of foreign origin but that are no longer regarded as foreign in the minds of the people and are indeed completely Germanized; these can continue to be used unreservedly (e. g., Hans, Johann, Peter, Julius, Elisabeth, Maria, Sophie, Charlotte, etc.). It serves the development of clan thinking to rely on previously used clan names . Very often, these will be Germanized names, which in the future will still indicate the origin of the clan in a specific German territory (e. g., Dierk, Meinert, Uwe, Wiebke, etc.).

Should basically receive only German names is a phrase that permits exceptions. There was no legal basis for this ministerial recommendation, and a recommendation is all it was. Even the current Reich and Prussian Minister of the Interior, referring to his own directive, wrote a good six months later:

Special regulations regarding given names still do not exist. It has simply been determined that given names of German citizens are in principle to be entered in the German language in the civil registry, and that indecent, senseless, or ridiculous given names may not be used.48› Reference

Everything seemed so open and above-board. To our astonishment, we find in the middle of 1938 clear and disturbing references in the press to developments on the name front – the military expression seems quite appropriate here. The name question had taken on another dimension since the end of 1937. The echoes in the press served partly as a trial balloon for what was to come, and may have been meant as a warning to be read between the lines about this new development. It was especially Germany‘s most famous newspaper, the Frankfurter Zeitung, that conspicuously followed the story of the naming question, and in the summer of 1938 published reports whose journalistic significance is hard to grasp for the modern reader.

In Mein Kampf, Hitler had assigned this newspaper to the bourgeois democratic Jew papers, to the so-called intelligentsia press, which, as he expressed it, wrote for our intellectual demimonde. 49› Reference By 1938, the Frankfurter Zeitung had long been without Jewish owners. In honor of the Fuehrer’s birthday the following year, ownership shares were to go as a present to the Eher Publishing House in Munich.50› Reference It should not be forgotten that this newspaper, which Hitler and Goebbels repeatedly wanted to finish off, was important for the foreign policy image of the Third Reich because a certain distance was perceived between the regime and the paper.

How far the editorial board could stand apart from the Nazis is not a question that can be answered here. In point of fact, there was no single editorial opinion.

Be that as it may, during this period the Frankfurter Zeitung reported on three occasions about our topic, one that was probably only of remote interest to the average reader. Two of these cases were quite important and were reported on in a manner that was unusual and striking for that period. We should consider it possible that this constituted an effort to warn the alert reader at home and abroad of hidden signals indicating an otherwise little-known development. Such signals could warn people, but they could change nothing.

In the Saturday edition of July 1, 1938, a short article entitled Restriction to Two Given Names ended with this sentence: Names of German origin are to be preferred. This was hardly anything more than the kind of signal mentioned above. The report itself was generally scanty. It was based on an article published in the Journal of Registry Office Affairs, by a Dr. Stoelzel, professor at the University of Marburg,51› Reference an article which could itself, however, be considered explosive. Stoelzel‘s relentless proposals went much further than the bureaucrats and even than the Reich Ministry of the Interior had dared.

Stoelzel, also a frequent contributor to this journal, and its expert on questions of marital status, complained primarily that the new marital affairs law of 1937 had allowed an unlimited number of given names, and he took a stand for a limit of at the most two given names. He painted a dire picture of what misuse could be made of an unlimited set of names, and he then switched over to the question of which names conscientious registrars should allow, which names should be denied, and what attitude they should take regarding the current demand to encourage the choice of given names of Germanic origin. 52› Reference

Stoelzel’s concluding recommendation went much further: he advised for the sake of simplicity to allow parents no choice at all or at the most a very limited one. German parents should have a choice only among names on two lists. Any names not found on either of these lists would henceforth not be considered for German children – that is, banned. These points remained hidden from the readers of the Frankfurter Zeitung, although this radical solution should have had greater publicity. After all, after about half a century of following this suggestion, German given names would have been reduced to a rudimentary inventory of scarcely more than a hundred, and for the rest of the Thousand Year Reich people would have had to resort to numbering their children instead!

On Sunday, August 7, and the following Thursday, August 11, 1938, the Frankfurter Zeitung published two items under the title German and Jewish Given Names. The sources for these articles couldn’t have been more different. One came from a legal decision on names from the Prussian Supreme Court on Civil Matters of July 1, 1938; the other, from an article drawn from the magazine The New Folk, a publication of the Office for Racial Policy of the Nazi Party.

In the August issue of this family-oriented illustrated magazine, heavy on pictures, Rolf L. Fahrenkrog demanded German names for German children. This was the article featured in the Frankfurter Zeitung on August 11, 1938, the day Esther Luncke was born. In an unusually subdued report, it cited a few passages without comment, then turned with the words In conclusion, the author writes to a rather amusing episode, which gives the impression that the whole article was similarly light-hearted:

A party comrade insisted to me that we must avoid un-German, and especially Jewish, given names. He proudly stated that his boys had beautiful German names, Georg and Paul. I had to disappoint him. Georg comes from the Greek and has the beautiful and proud meaning of farmer. Paulus is an old Christian name of Latin origin, meaning small, modest. This name developed like Johannes. They were ‘Germanified,’ so to speak. From Georg we have forms sounding like old German, like Joerg, Joern, Juern, or Juergen, but that doesn‘t alter the fact that its origin is not German.

The original doesn’t sound so easy-going; there the author ended with the following appeal:

We desire to and should stand fast on this point — Our children, who are born German and are educated in the Folk Society of the Third Reich as pure German people, should bear truly German names that correspond to the true value of our German blood. There are no justifiable grounds to give them un-German names; in fact, there are many reasons not to. Everything supports the demand of GERMAN NAMES FOR GERMAN CHILDREN!53› Reference

Completely lacking in the Frankfurter Zeitung article were the vehement anti-Semitic outbursts with which Fahrenkrog punctuated his article, aside from various incorrect or at least questionable etymological derivations.

Hardly any other people is as rich in beautiful, praiseworthy, but still distinctive family names as is the German people. And if Jews have acquired them or are attempting to acquire them today, it is their unmistakable intention to conceal themselves behind the variety of these German name forms so that they can continue undisturbed to pursue their Jewish business. Jewish name camouflage has been so successful that today there are real live Jews bearing the names Mueller or Schmidt who are immediately accepted as Folk-Comrades by trusting and naive Germans.

Since in every marriage in Germany the maiden name of a woman is replaced by the family name of her husband, and the children of such a marriage bear only these family names, this results in every case in the „disappearance“ of the mother‘s maiden name, whether Jewish or not. Fahrenkrog cannot have been referring to this standard situation, though he was hardly concerned with logical argumentation. He was on a hateful rant against Jew names, that is, Jewish given names, without giving rational reasons (assuming there were any). So he thundered:

For the National Socialist German, who is obviously an enemy of the Jews, it is selfevident that no Jewish names should be chosen. His children have a natural right to bear German names.

All this lay hidden from the reader of the Frankfurter Zeitung. Such a reader was told only that another person had demanded German names for German children. It is not clear what the editorial board hoped to do by so basically changing the content and the purport of the article in question as to render it seemingly harmless.

The introductory sentence of the article in The New Folk is striking for another reason. There — and thus in the Frankfurter Zeitung — the subject is a recently released directive of the Reich and Prussian Minister of the Interior, according to which Jews from then on should bear only Jewish given names. Since this sentence appears in the August issue of The New Folk, and on August 11, 1938, the Frankfurter Zeitung already cites this article, the phrase recently released directive can refer only to a directive published shortly before August 1938. But there was no such directive! Not yet. It appeared exactly one week after the article was published in the Frankfurter Zeitung, that is, on August 17, 1938. Guidelines on administration appeared on August 18. While writing his article for the August issue, the author must have assumed that the directive would have already come out. Where he got his information is an open question.

The other article, German and Jewish Given Names, had appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung on August 7, 1938, and concerned a decision of the Supreme Court on Civil Matters in Berlin of July 1, 1938, published August 5, 1938. The Private Telegram of the Frankfurter Zeitung column began with these words:

A registrar is not obligated to register a typically Jewish given name for a pure-blood German child. In one sentence, that is the essence of the decision pronounced on July 1 by the Prussian Supreme Court on Civil Matters and published in German Justice.

The trial involved the name Josua (Joshua in English), which a forest ranger named Lassen from Marienwerder had intended for his son. The name was rejected by the Supreme Court as typically Jewish. The version published in the professional journals would have been available to the responsible registrar in Gelsenkirchen when he was to decide about the given name of Esther. Pastor Luncke, had he read the Frankfurter Zeitung of August 7, 1938, could not escape the conclusion that in the view of the Supreme Court the name Esther as well would be considered typically Jewish and thus not admissible for German children. Following the reasoning of the Supreme Court as conveyed in the Frankfurter Zeitung, this fate was to be shared by the name Esther with the names Josua, Abraham, Israel, Samuel, Salomon, and Judith. Consequently, the registrar in Gelsenkirchen refused to enter the name Esther in the book of births, since it was a typically Jewish name.

No more talk about senseless, ridiculous, or offensive – typically Jewish was now enough. Typically Jewish as a grounds for refusal was new. That’s why the Josua decision of the Supreme Court merits closer consideration. It must be read under a magnifying glass to understand it depths and its shoals. After all, this decision is one of the two most important decisions on the law of names made by the Supreme Court on Civil Matters in its role as an authoritative court.

The king loved Esther more than all the other women, and she won his grace and favor more than all the virgins. So he set a royal diadem on her head and made her queen instead of Vashti.

Book of Esther, 2:17

Andrea del Castagno c. 1450

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.