Полная версия

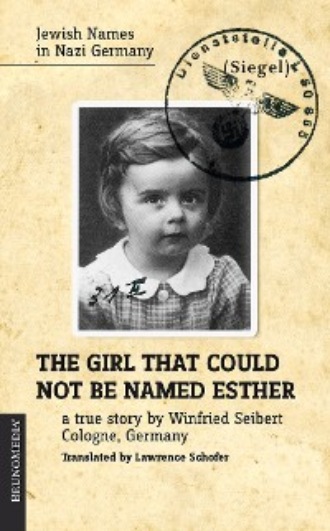

The girl that could not be named Esther

So now it came down merely to a choice between Gladbeck or Gelsenkirchen, two medium-sized industrial towns. At first it seemed more important to look for records in the Essen courts, and if not there, perhaps in the state archive in Dusseldorf. It turned out that the records of the district court in Essen had been destroyed in 1976. They had survived the war, but they had not been considered significant for modern history and had therefore not been archived. They certainly would have been worth keeping. We had lost a small historical possibility. Now the records were irrevocably gone.

It’s true that the lawsuit register at the district court in Essen provided an important clue, but the letter came a few days too late. Barely a week earlier I had solved the puzzle.

First I have to report on another false turn. Once the search had been narrowed to Gelsenkirchen and Gladbeck, I could concentrate on looking for Pastor L. in these two places. There could not have been many pastors whose names started with “L” in 1938 in Gladbeck or Gelsenkirchen. With the help of the Protestant Church Office in Cologne, I soon knew that at that time there were no pastors “L” in Gladbeck, but there were two such in Gelsenkirchen: Johannes Karl Leckebusch, born 1882, pastor in Gelsenkirchen-Buer starting November 1930, and Theobald Lehbrink, born 1898, pastor in Gelsenkirchen starting November 1933. Both were still of an age to be fathers in 1938.

To be sure, Pastor Leckebusch, 65 years old in 1938, seemed less likely than Pastor Lehbrink, who was 16 years younger. Besides, Lehbrink had additional interesting personal data. On January 31, 1939, he had retired from the active ministry. Why? He was barely 40 years old and had another good 25 years of service ahead of him. It could be that he had to quit the ministry because of his hard-headed confrontation over the name Esther, or it could have been that his church, to protect him, had cautiously relieved him of his duties because of the stand-to with the Nazi state. Besides that, he had published something in 1935 about God and authority, a very Protestant theme, which might have gotten him into trouble. After the war he wrote something about Arminius, the Teutonic opponent of the Romans. This too led me to believe that he was no run-of-the-mill pastor. He seemed likely to have been a pastor who took on the Third Reich in other articles as well – Theobald Lehbrink could be my man!

He had died in 1962 in Dassel, near Hanover. In 1941 he had remarried. Whether his first wife — Esther‘s mother, if he was the right one — had died early or if the marriage ended in divorce could not be determined from the short biographical data. If however he had divorced between 1938 and 1941, this could also explain his withdrawal from the ministry.

If he was Esther‘s father, and if Esther, under whatever name, was still alive, then there must be evidence in the estate papers. A call to the district court in Einbeck revealed that there were records of the estate, but they were in storage. By telling the person in charge that there were some copyright issues to clear up in connection with the pastor’s literary efforts, I was able to obtain — somewhat irregularly — a copy of the certificate of inheritance. Luckily, two days later I could discard it since other inquiries had shown that Pastor Lehbrink could not have been the mysterious Pastor L.

A telephone call to the church office in Dassel took me to a helpful woman who, as luck would have it, not only had known Pastor Lehbrink but had even been confirmed at the same time as his daughter. Even though this confirmand had been named Gisela, this did not mean anything since our Esther was originally not allowed to be called so. But the birthdate! After looking in the church records, the friendly woman said that Gisela had been born on May 18, 1939. Again nothing. With that birthdate, she could not have had an older sister born August 11, 1938.

Now what? There were two Pastors L. in Gelsenkirchen, and according to the list of Protestant pastors in Westphalia from the age of the Reformation down to 1945 only these two were of the right age, and neither one was the right one. The one to whom a lot of the evidence pointed was Lehbrink, but he wasn‘t the one. As it turned out, I almost had the fox guarding the henhouse. On May 8, 1992, the State Church Archive of the Protestant Church in Westphalia wrote me:

Unfortunately, on the basis of the available documents, we were unable to confirm your assumption of the possible paternity of the Pastor and Superintendent Theobald Lehbrink of a daughter named Esther, born August 11, 1938. Since Pastor Lehbrink numbered among the German Christians [Nazi-oriented breakaway church group], it is quite unlikely that he would have chosen such a name.

That was stated quite modestly. Lehbrink, as it later was shown, was an almost fanatical National Socialist with a rigid belief in the Fuehrer, or at least that was the way he expressed it in his Christmas 1935 tract on God and authority, as we shall later see. It is impossible that such a pastor, who stood so close to the Nazi-faithful German Christians, would have caused such a row over the name Esther in 1938. Why Lehbrink left his ministry in 1939 could not be explained. That wasn’t important now. What mattered was that Pastor L. was still unknown.

I didn’t know what to do next. Perhaps I had gotten carried away. Court decisions are not published with the purpose of identifying the parties to the dispute. But I only wanted to find the little girl Esther, born on August 11, 1938, in G., apparently Gelsenkirchen. I will never forget the decisive long-distance telephone call that ended my search.

On May 7, 1992, I reached a very friendly woman at the registry office in Gelsenkirchen, who was really surprised at what I had to ask her about. In 1938, I said, some 5,500 births were registered in Gelsenkirchen. That would come out to an average of about 15 children a day. Statistically, there must have been some seven little girls registered on August 11, 1938. Could there have been one or more whose family name began with “L“?

Luckily, the woman had become curious. It didn’t take more than two minutes for her to confirm that on August 11, 1938, the birth of a girl with the surname L. had been registered. That MUST have been Esther. But she couldn’t say – on account of the data protection law. I then explained why I was looking for this girl. Yes, she said, I was at the right place, and then she read next to the given name Elizabeth a subsequent registration of the name Esther in 1946. Unfortunately, she could not tell me the family name. She was really very sorry, but I had to understand.

We quickly established that the family name was neither Leckebusch nor Lehbrink. That used up the only two pastors L. in Gelsenkirchen. I was so to speak standing in front of the open birth registry book with the entry I was seeking, and I had forgotten my glasses. Esther was so close, but I couldn’t get any farther. I could only conclude that this Pastor L. had not been a pastor in Gelsenkirchen, and that the child had been born more or less by accident in Gelsenkirchen. We had had that problem in Gubin.

The woman understood my despair. When she heard my deep sigh and my utterance that a name starting with L must continue with a vowel and that there were only five of these, she suggested that I start at the end of the alphabet. In addition, she raved about the women’s hospital in Gelsenkirchen, which was always popular with mothers from Wattenscheid, a small town that is now part of the city of Bochum. – That was the answer!

Pastor L. came from Wattenscheid, and Esther had come into the world at the hospital in Gelsenkirchen. The presumed typo of “W” in place of “G” was not an error; both letters were correct. Suddenly, everything fell into place. After a lightning visit to the church office and a look at the centuries-long list of Westphalian pastors, it was clear that the name of Pastor L. was Friedrich Luncke.

He had been born on July 10, 1908, the son of a miner in Heeren. After a short interlude as an assistant pastor in Spenge, he was inducted as minister in Wattenscheid-Leithe on April 4, 1937, where he remained until July 31, 1973. He died on September 16, 1976. His first wife, the mother of the Esther I was seeking, had died in 1966.

A call back to the registry office in Gelsenkirchen erased all doubts. The name was correct. Now I had only to find out what had happened to the little girl who had received the name Esther after the war and where the 53-year-old woman was now to be found.

At this point I am going to break off my reciting of the report for my daughter. The end of the story belongs at the end.

He was foster father to Hadassah

— that is, Esther — his uncle’s daughter, for she had neither father nor mother. The maiden was shapely and beautiful; and when her father and mother died, Mordecai adopted her as his own daughter.

The Book of Esther, Chapter 2, verse 7

Marc Chagall, 1960

Chapter 2

It happened in 1938, in a critical year for German history, a fateful year for lots of people.4› Reference In its Esther decree of October 28, 1983, the Prussian Supreme Court for Civil Matters wrote of a great and meaningful year, great and meaningful for Germany. The Watchword of the Week, a colorful Nazi Party wall poster, celebrated 1938 as a God-blessed year of struggle, which even after a thousand years Germans will speak of with pride and reverence. 5› Reference Great times, great words.

In October 1938 the Prussian Supreme Court for Civil Matters issued the last word in the Esther case, or at least for all those involved it was the last word: A non-Jewish German girl, daughter of a pastor, whose parents wanted to name her Esther, could not be named after the biblical Queen Esther because the Supreme Court considered the name to be typically Jewish. Such a name was out of the question for a German child.

The Supreme Court did not have an easy time explaining the grounds behind its decision. The very extensive legal reasoning allows us a view into the mental world of the three judges, on whom the God-blessed year of struggle had left its mark.

Such decisions are easy to criticize. From today’s point of view, everything appears clear and readily understandable; Good and Evil can be cleanly separated. People are often smarter in hindsight. Still, a person may ask himself despairingly, how did they come to such decisions, how could they have arrived at such gross and spiteful legal grounds? How did it happen that the presumably quite sharp minds of the judges were so befuddled? In the attempt to understand the decision and those responsible for it, you have to get closer to the spirit of the times, no matter how much you believe that the spirit was evil, embodying the demonic character of those years. You have to consider this spirit of the times because otherwise you won’t understand anything.

Even though the Berlin proceedings concerned only the given name of a Christian girl, the controversy over Esther’s name revolved completely around the Jewish Question. Almost everything at that time revolved around this phenomenon, whose meaning for the party comrades of the year 1938 cannot be grasped from today’s point of view by rational consideration alone.

The Jews in Germany formed a minority of less than 1% of the population. At the last census in 1933, 502,799 persons of Jewish faith were counted, including 94,717 foreigners, mainly Poles.6› Reference 160,000 of these people, a good third of all the Jews in Germany, lived in Berlin, making up 5.33% of its population. At the beginning of 1938, before the annexation of Austria, the German Reich had 68 million inhabitants, including some 300,000 so-called persons of the Jewish faith. That came to 0.44% of the total population.

It was well known that Jews were heavily represented in several economic sectors and professions. This was based on historical grounds, which were connected with the restricted rights of the Jews in Germany over the centuries. German Jews also contributed to Germany’s scientific fame. Of the fourteen German Nobel Prize winners in chemistry, four were of Jewish origin.7› Reference Of the Nobel Prize winners in physics, three of the twelve German laureates were Jewish,8› Reference and in medicine, three out of seven.9› Reference These were numbers to be proud of, but they didn’t help at all.

By the beginning of 1938 — a good 200,000 Jewish Germans had meanwhile left the increasingly dangerous country — the concentration in Berlin had become even greater.

128,000 Jews still lived in the capital, some 43% of all Jews remaining in Germany. Their proportion of the Berlin population had sunk to barely 3%.10› Reference Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels exerted deliberate pressure on them, as he noted in his diary on June 11, 1938:

Lectured to over 300 police officers in Berlin about the Jewish question. I really stirred them up. Oppose all sentimentality. Don’t worry about the law; harass them. The Jews must be driven out of Berlin. The police will help me in doing that.

The Germany of 1938 had grown larger. With the annexation of the so-called Eastern Marches (Ostmark – a centuriesold term for Austria), the population of Greater Germany had grown to 76 million. Bringing in Austria had brought in another 180,000 Jews, now totaling 0.63% of the German population.11› Reference

And yet this tiny minority stood at the very center of the thinking and aspirations of the National Socialist government. The judiciary was also fixated on this minority in the way it persecuted them, excluded them, and deprived them of their rights. These judicial activities cannot be explained away or excused with reference to loyalty to a positivistic reading of the law, in which the judges were bound to follow the letter of the law literally. The wording of many, many decisions makes it clear that nothing here can be excused.

Seen from a modern foreshortened perspective, the year 1938 was especially notable for the annexation of Austria, the crisis of the Sudeten area of Czechoslovakia which ended with the Munich Agreement, and, most significant for us today, the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht) with all its fearsome consequences. The Germans of 1938 were unaffected by the persecution; they went about their daily lives. The propaganda machine of the ever-more-arrogant Greater German State churned out reports of successes. There were quite a few of these, serving to distract people from the difficulties of daily life. The economy of the Third Reich was, strictly speaking, heavily indebted, if not over its head in debt. Rearmament and the attempts at full employment had their price, though of course nothing of this appeared in the papers. Foreign policy successes might make people euphoric, but they did not fill the state treasury. From time to time the state needed to throw the dog a bone. The grass roots, the party faithful, demanded their due.

The press reported in much greater detail the August 1, 1938 introduction of the plan for the common people to save for a private automobile than it reported the burning synagogues of November 10. Isn’t this what people actually wanted to know about? All the same, we may still be curious to know what there was to fear, to see, to hear, and to suspect before November 10, 1938.

Life for the non-Jewish Volksgenossen, National Comrades — by definition, there could be no Jewish National Comrades — life for the National Comrades in 1938 went on as normal. To most Germans, conditions may have appeared better than in previous years. This came out in the birth rates. The number of births in 1938 in the country as a whole rose to 1,493,000, the largest number since 1922. That corresponded to 19 births per 1,000 inhabitants (compared to 8.7 in 2005). Still, the Journal of the Office for Racial Policy of the National Socialist Workers‘ Party (the Nazis) noted in a warning tone:

There were still lacking another 148,000 live births, some 9%, for the birth rate needed to maintain the strength of the people and its military power.12› Reference

The Olympic Games of 1936 had brought success, fame, and international prestige. The Nazi system had restrained itself for the sake of this international renown, and had even cut back on the harassment of the Jews in Germany, at least on the surface. What lay dormant in the heads and in the desk drawers of the Party comrades and the Party organizations was not visible. The situation was comparatively quiet; the Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) and the rowdyism of 1933-1935, the early years of Nazi rule, seemed to have subsided. Actually, it was only the lull before the storm.

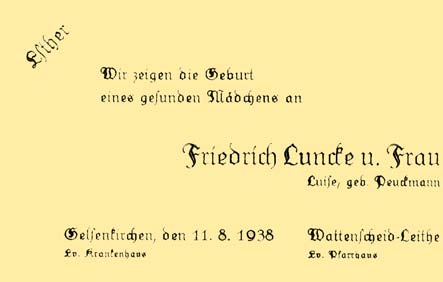

The little girl who was to be named Esther was born on August 11, 1938, in Gelsenkirchen. The baby was healthy, 52 centimeters (20.5 inches) long, and weighed 3150 grams (6 pounds, 15 ounces).

ESTHER

We announce the birth of a healthy baby girl to FRIEDRICH LUNCKE AND WIFE Luise, nee Peuckmann.

Gelsenkirchen, August 11, 1938, the Protestant Hospital Wattenscheid-Leithe, Protestant Parish House

One month later, on September 11, 1938, the father, Pastor Friedrich Luncke, baptized the baby in Wattenscheid with the name Esther. To be sure, the child had no official given name because the State Registry Office had refused the name Esther. For the state, Esther had no name.

The baptism was not only somewhat late; it was now a conscious act of protest by the father. After the Registry Office had refused the child the name which he desired, he had gone ahead and baptized his daughter with the beautiful name of Esther. He and his wife stood firm with this name; let the Registry Office official decide whatever he wanted. To be sure, the Lunckes had thought about the choice of a name long and hard.

They were familiar with the biblical book of Esther and the wonderful story of the beautiful Jewish girl in the Persian diaspora who found favor in the eyes of the king and had been elevated to the position of Queen Esther. They were touched by the dilemma of Esther, torn between conflicting duties. She would have to disregard a command of her husband the king, something punishable by death, if she wanted to save her people from a threatened pogrom. She overcame her dilemma with the determined words, If I perish, so I perish.

According to Jewish tradition, Esther is numbered among the four most beautiful women in the history of the world. That doesn’t have to be taken literally, but one can certainly see from the story that the biblical Esther combined beauty with courage. As parents are wont to do, you could read a lot into this name, a name resounding with wishes and hopes.

As thoughtful readers of the Bible, the Lunckes must have been aware that the Book of Esther also presents problems. No matter whether this was a pious tale or not, they would have had their doubts about the fact that Esther’s courage in saving the Jews in Persia was sullied by the alleged death of 75,000 Persians – a thoroughgoing counter-pogrom going beyond pure defensive measures. This was no simple story with simple answers. It was vigorously debated among theologians.

But it was just that circumstance that made the name so much more endearing to the Lunckes. They had set their hearts on this name. It involved threats to themselves, will power, personal courage to stand in opposition, hope for salvation from an apparently omnipotent evil. Haman, the biblical enemy of the Jews, was equivalent to Hitler – that fit in with the spirit of the times. And they weren’t alone in their parish house in Leithe. Pastor Luncke was part of the Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church) subgroup within the dominant Protestant grouping in Germany that early on began to oppose the Nazis. As early as 1934 the Confessing Church had suggested sermons to its pastors on the book of Esther to show that every enemy of the Jews, like Haman, would come to a bad end.

In a less belligerent manner, even rather meekly, the Carmelite nun Teresia Benedicta a Cruce, better known as Edith Stein, at that time viewed herself as a very poor and defenseless Esther, who like the Biblical Esther was taken from her people so that she could represent them before the king. 13› Reference

The registry official in Gelsenkirchen had refused to register the name Esther. The birth certificate of August 13, 1938, identifies the child as a girl without a given name. There is no trace of this conflict on the birth announcements sent to friends and acquaintances. The birth of the daughter Esther is expressed simply there. On August 15, Pastor Luncke reported the birth of his daughter Esther to the Protestant Church Consistory in Muenster and from then on received an extra child allowance of 10 Reichsmarks. His monthly salary thus rose to 330.89 Reichsmarks.

The legal battle for the correct given name went through three levels of courts, and finally ended with the decision of the Prussian Supreme Court for Civil Matters in Berlin on October 28, 1938. It was only on December 3 that the little girl received an official name – Elisabeth, not Esther. Esther was inadmissible. The registry office could close its records. The state had won out. But that was not the end of the story, not by a long shot!

Esther was the first child of the pastor and his wife, who had gotten married on April 29, 1937, and shortly thereafter had moved to the big parish house in Leithe, a neighborhood in Wattenscheid, a working-class town in the Ruhr Valley. Luise Luncke, maiden name Peuckmann, two years older than her husband, had studied German and theology at the university. In order to be able to devote herself to working alongside her husband in the community, she gave up on her goals for an independent career. She worked hard, with no regard for her own health. She died at the early age of 60.

Friedrich Luncke had studied theology with Rudolf K. Bultmann, said to be one of the most influential theologians of the 20th century, one who wished to remove myth from Christianity while staying true to his faith. Luncke knew Greek and Hebrew.

Pastor Luncke was no ivory tower scholar; he was a fighter and a great preacher before the Lord. He studied the Bible in the original; and he worked on his sermons, in which he did not shy away from confrontation with the state. In general he was very conscious of what he was doing, and he was determined to live that way in times that were hard for an engaged Christian. He set about working with all his might for his congregation. That brought him negative publicity and quickly got him in trouble. On January 6, 1938, he was arrested by the Bochum branch of the Gestapo, though he was released three days later. The affair concerned the Investigation of the League of Women in Leithe14› Reference , but no further details are available. He had been warned.

Luncke did not let himself be scared off. True to his nature, he remained uncompromising, a most obstinate gentleman. In the matter of stubbornness bordering on pig-headedness, he was a true son of Westphalia.

In 1934 Luncke had become assistant pastor in Spenge, a working-class district with major social problems.

In only seven months — the church authorities did not leave him in Spenge any longer than that — he had won over the workers, the socially weaker portion of the church congregation. He did not keep his distance from them, but rather he approached the workers in the cigar industry. He had an understanding of their needs and visited them in their meager living quarters. As the son of a manual worker, he found the right tone to address them in. When he preached on a Sunday, the church was jammed to the eaves.15› Reference

He may have been too socially conscious, to the point where the church elders did not go along with him. Here is what he was like: An older woman was crossing the street with a wheelbarrow. Luncke went up to her and said, ‘I’m going the same way as you. I’ll push the wheelbarrow.’ That caused a sensation in Spenge. Someone like that couldn’t be allowed to stay.16› Reference