Полная версия

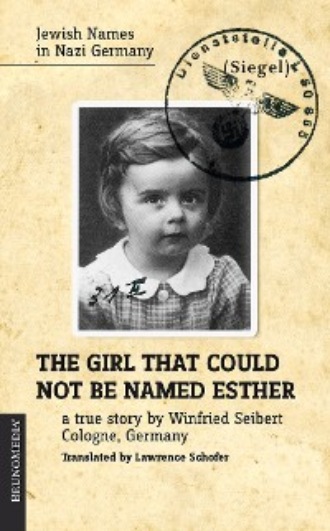

The girl that could not be named Esther

dedication

Dedicated to my daughter Esther

and her brothers Daniel

and Raphael

Summary

You can’t name her Esther. And you can’t name him Joshua. These are not truly Germanic names. – German bureaucratic and judicial decisions in 1938.

Residents of English-speaking countries are in the main accustomed to naming their children with any name they want. Other countries are not so permissive, requiring an approval for registration of names. In countries with a Christian tradition, a distinction is drawn between family names and given names, also called baptismal names or Christian names. In Germany this was customary as long ago as the 14th century. So long as there were no state registration authorities — that is, no office of vital records — and, to simplify a complex process, before the division of church and state, the church was responsible for putting order in names. Names of false gods or pagan heathens were frowned upon, while names of recognized saints and Biblical figures were desirable. It was impossible to give a non-Christian name to a Christian.

Similar restrictions on the choice of names arose after the Revolution of 1789 in France and in practically all European countries. Not so in the USA – there the law on personal status never developed in a fashion similar to that in Europe, and the resulting customs are correspondingly looser. Whether freedom is totally unlimited is hard to say, but the freedom there has led to varieties of names, which, when extravagant parents load extravagant names on their children, can develop into significant problems for the children. Whether Geronimo, son of the bassist Alex James, will later be happy with his name, will depend very much on how he regards the history of Indians in his country. Elijah Bob Patricius Goggi Q may let himself be reduced to a simple Elijah Bob, but this still leaves the question open of what the “Q” stands for in this name of the son of the front man for Bono. Whether Sharleen Spiteri of the pop band Texas thought of any joy to be brought her in writing her name as Mysty Kyd or whether she thought about her daughter, we probably will never know.

In Nazi Germany, this ordinarily innocuous law became part of the racist arsenal of the regime, a regime that had enthusiastic adherents all through the bureaucracy and the judicial system.

An article in a law journal caught the eye of attorney Winfried Seibert, born in 1938, and he set off on an ingenious search of German history in the Nazi period, looking for the girl who couldn’t be named Esther.

A determined pastor in a small town in the Ruhr Valley demanded in 1938 that his daughter’s name be registered as Esther. He ran into bureaucratic opposition and fought his case through the courts all the way to the Supreme Court for Civil Matters in Berlin. He lost. So did a park ranger, who wanted to perpetuate the family name Cuno Josua.

What the author has done in this book resembles the unfolding of a mystery story. Who was this minister, identified only as the Minister L. from the town of W.? Why was he so hard-headed? Who were these local officials who so adamantly defended the purity of German names? What kind of justice system enforced these laws?

The author started with L. from the town of W. With some ingenious detective work, he found the town, the likely person, and then even the son of that courageous pastor — though not the daughter Esther.

This book is a very close examination of the people involved — the minister, the bureaucrats, and especially the judges. The author reconstructs the life stories of the three judges who sat on the Supreme Court. Interestingly, the judges found that Esther was a criminal prostitute of the Jewish race, while Ruth, a name that one might expect to be condemned in the same way, was allowed as a Germanified name.

The book contains a fascinating reconstruction of the German justice system based on the use of this single case.

Through the use of this case, the readers sees the Nazi justice system and Germany itself through its pogroms and then into the war period itself. Instead of relying on masses of data and statistical compilations, this book energetically and passionately moves through the daily activities of Nazi justice. The unfolding of these items is a gripping tale that caught the attention of tens of thousands of German book-buyers and of reviewers throughout the German language press in Germany and in Israel (originally published in 1996).

And what of little Esther, who was denied her name so that she would not be embarrassed when she would be taken into the League of German Girls? Named Elisabeth by the officials, the author found notice of her baptism in 1946 as Esther. Unhappily, the search showed that the little girl had died of a childhood disease at age 2½, but her father had preserved her memory by renaming her after the defeat of the Nazis. The pastor himself served in the German army, but continued to incur the wrath of his superiors for his sermons, which used ambiguous language to denigrate the German leadership.

Foreword

This is a story taken from the everyday workings of the legal system under the Third Reich, the Nazi regime. It is limited to a minor event that involved only a few people, but I think it is symptomatic of a much larger story.

The Nazis had no great love for the judiciary; nonetheless, that group certainly did not produce any resistance fighters. Judges just didn’t do that sort of thing. The judges kept up the pretense of business as usual; they adapted. It’s true that they were subject to the pressure of the National Socialist state apparatus. Judges were kept on a short rein by judicial instruction letters that made a mockery of judicial independence. Many of the judges let themselves be coerced, suffering from more or less of a bad conscience, into giving the National Socialist system what they thought was its due because it was, after all, the State.

Thus, for the German judges, May 8, 1945, the date of Germany’s surrender, was a day of liberation. Their grateful commemoration of this event has filled tomes. Unfortunately, these have all gone missing. Or is there more to the story?

In the early post-war years, we were subjected to attempts at forgetting, at concealing, at hushing up, and even out and out lying. The first president of the new Federal Court of Justice created after the war, Hermann Weinkauff, is responsible for a multi-author study of the judiciary in the Third Reich – happily, he never completed it. The book is noteworthy only for its self-excusing tone, not for any attempt at a critical look at the institution. Others had previously described the judges in the Third Reich as victims of their training in legal positivism. They had merely applied the letter of the law as it had been laid down by an unscrupulous legislature. That was the grand illusion of the postwar judiciary in West Germany. The legal historian Bernd Ruethers made the first attempts in 1968 to come to terms in a scholarly way with the distortion of the law and of legal decisions in the Third Reich.

But that is not what this book is about. I am reporting here only about three decisions handed down by the Superior Court in the year 1938, in which it was decided what given names a person could have if he or she was born under the Third Reich. These three decisions by a central court have not yet been subject to scrutiny, even though they lead deep into the secret heart of National Socialist justice. It is often said that, at least in the case of civil law, the judges managed to stand firm against their Nazi masters. After all, civil law concerns itself with everyday matters, such as rent problems, contracts, social issues, and, as we shall see, the question of what names a person could have. But the truth is that the judges did not stand firm on such issues, not by a long shot. Their decisions and their findings formed only small building blocks of the structure of an unjust state, but they were still part and parcel of the injustice that was done.

That injustice prevailed is clear from the decisions discussed in this book. Although not one Jewish person was involved in this legal procedure involving names, under the surface the whole affair was about Jews and nothing else. These decisions and the others cited here formed part of the fight against the Jews, which the Third Reich pursued to the bitter end. Can the judges thus be made to share the responsibility for that horrible end? Can one reproach them with making judgments and decisions that undoubtedly contributed to stripping the German Jews of their rights under the law, decisions that helped pave the way for the final solution? In their decisions, the judges adopted the National Socialist body of thought and thus made it socially and judicially acceptable. Didn’t the language of their decisions, couched in Nazi jargon, contribute to the maltreatment of the Jews in Germany? Didn’t all this lead to the loss of respect for Jews as fellow human beings that played a major role in their destruction?

One could answer — and this is how the answer usually comes out — that nobody could have foreseen the assembly-line annihilation of the Jews that came later. Occasional excesses, yes, one would have to reckon with them, but nobody thought about death camps. That would have far surpassed anyone’s imagination. There is no obvious answer here. Perhaps it makes more sense if one separates the evaluation of judicial decisions from the overarching theme of the final solution.

One has to try to imagine what the fate of the Jews in Germany would have been if the dictates of the court had been followed and the National Socialist dictatorship had not dared to carry out the exterminations. What if the everyday life of German Jews had been determined only by harassment by the bureaucracy and the party with the blessings of the judicial system? How would they have experienced life starting in 1939?

The situation of 1938 would have developed into an ongoing state of affairs. The German Jews would have lived in a state that had undertaken not to protect its Jewish citizens any longer; instead, it would deprive them of their rights under the law and punish them wherever possible. They would have to vacate their homes and move to buildings owned by Jews. This would eventually lead to concentration in a modern ghetto. Contact with the outside world would be unwelcome. Contact perceived as sexual in nature with people of German blood would be punishable by law. Children’s given names would be restricted to an official list issued in 1938. School and university attendance, the use of libraries, and a thousand other things would be forbidden to the Jews. They would not be able to work as physicians, attorneys, real estate brokers, guides for foreigners, or in credit agencies. Even street peddling would be forbidden. Public transportation would be off limits. Synagogues would be burned down. Significant Jewish property or Jewish firms in general would cease to exist. All of this would have been taken away from them, stolen, taxed away, Aryanized. There would be no right to vote; there would not even be any elections – and no hope.

Such are the conditions under which the German Jews were living at the end of 1938. Even without war and extermination, the steady policy of elimination of Jews would have gone on. These were exactly the conditions that the judges, with their verdicts and their decisions, had approved: a master race barely tolerating on the outermost fringe of society a guest people of lepers, deprived of all rights, plundered, despised, and outcast. And prevented from fleeing. Not enough to die of, but too little to live on.

And that would be perfectly acceptable. The purity of German blood would be assured. Any danger of contact with Jews was nipped in the bud, to quote the Superior Court. No half measures here – the separation would be complete and unambiguous. And it would be legal as well because German judges had determined the conditions to be correct under the letter of the law.

That’s what they have to answer for. That immeasurably greater damage would still come – that can be no excuse. The struggle of the National Socialists against the Jews was a war; that is how it was understood and carried out. Matthias Claudius’ lament, It’s war! It’s war! ... It’s unfortunately war, and his closing plea, and I wish it were not my fault, would have been fitting words for many of the German judges. Unfortunately, they weren’t the ones to say them.

If we want to live in a moral state, in a society that does not have to avert its eyes from its own history, then we must face up to this part of the past as well, not overcome it, but come to grips with it.

This is as true for the still virulent past of the National Socialist regime as it is for the more recent German past, for the unjust system of the German Democratic Republic. The necessary grappling with the past cannot be considered closed so long as it is not really over. Trying to prematurely bring to a close the process of honest confrontation with what has gone before comes at the high price of some longlived psychological damage.

This book is not concerned with simply repeating judicial verdicts and decisions. In order to really grasp their significance, it is necessary to conjure up an image of the actual people involved. After more than a lifetime has passed, this is not completely possible, but it will be attempted here. In the end, a frightening normality can be discerned in this story that makes one afraid that we have not really precluded every danger of repeating what has gone before. The language used to describe minorities is a reliable gage here, for the process of violating human dignity begins with words themselves.

A personality like Esther, who played such an historical role, though not through open and above-board negotiations, but through tricks, deception, and misuse of her bodily attractions and of her position, such a criminal prostitute of Jewish race can stand for nothing to the German women of our time and above all cannot be looked on as a personality after whom German parents should name their children.

Kammergericht, 28.10.1938

Chapter 1

The Prussian Supreme Court (Kammergericht) had issued its judgment on the given name Esther on October 28, 1938. It had rejected it as typically Jewish and had forbidden the parents to name their daughter Esther. At first — it was summer, 1989 — I had before me only the decision of the Supreme Court as published in the Juristische Wochenschrift (JW) – (Legal Weekly). This gave me the impetus to look more closely into this decision. Being myself the father of a daughter named Esther, born in 1983, I liked the name very much, and the expressly malevolent dealing with the name and the Biblical story of Esther affected me greatly. I wanted to know more, more about those involved, the judges and the little girl named Esther.

The records of the Berlin proceedings were no longer to be found. According to information from the Court, they had been burned in 1945, and anything that was left had been taken by the American soldiers. I had nothing more to go on than the published decision. The initial data for such a search were quite meager.

Section 1b of the Senate of the Supreme Court had made the decision. The only thing I knew was that this Senate was not responsible for Greater Berlin. The actual content which might have helped me further was sparse. It concerned the birth on August 11, 1938 of a daughter to Pastor L., who had registered the birth at the Registry Office in G. The mayor of G. had participated in the proceedings. G. at that time must have been an independent city, not located in a county. So the first thing to do was to locate the city G.

By the middle of 1992, I had achieved my goal. At that time I summarized the search for our Esther in a written report. It went like this:

I assumed — I had no doubt about it — that G. was to be found in Brandenburg, a province in the central-eastern portion of Germany, adjoining Berlin. In the completely altered world since fall 1989, when the wall had come down, this was a particularly exciting task. Maybe that‘s why it was so easy to make a false assumption. Since September 1991, I had represented the newly founded state of Brandenburg in the soon-to-be reunited Germany for its Establishment under Article 36 of the Unification Treaty, and I was also advising the East German Radio Network for Brandenburg (ORB) in its initial phase. Everything seemed quite simple – in 1938 the independent city G. in Brandenburg could only have been the city of Gubin1› Reference .

My query of October 16, 1991, to the registry office in Gubin at first went unanswered. I had unexpected difficulties in making a telephone call there because my office first had to find out that the listing was not under Gubin, but under the East German name of Wilhelm-Pieck-Stadt Gubin2› Reference. Finally I learned that the new Gubin lay left of the Goerlitz branch of the Neisse River — that is, in East Germany — while the old city, with the town hall and the courts, lay on the right bank of the Neisse and had thus become Polish. The archive in Zielona Gora, previously Gruenberg, responded with a cordial letter and the report of my being dead wrong. There were no registry documents and no church records for our Pastor L.

If you are stuck, you ask the press. Other than that, I hoped to find in old newspaper records at least a birth notice of a little girl born on August 11, 1938. Maybe even with the name Esther, since for a few days after the birth the ban on this name might not have been communicated to this family.

All this activity made a big commotion, both in Gubin and around Gubin. The newspaper Lausitzer Rundschau was extremely helpful; it even did research on its own — ultimately all in vain — at the church supervisory office regarding Pastor L. On March 19, 1992, it issued a call to its readers:

The RUNDSCHAU has received an unusual letter from an attorney‘s office in the previous West German Republic. He is seeking documents and information regarding a certain Pastor L. and his daughter born August 11, 1938, in Gubin...

The attorney’s office is interested as well in finding this daughter, who apparently was born on August 11, 1938, and whose parents wanted to name her Esther. In accordance with the demonic spirit of the Nazi era, this name was rejected with somewhat fearful reasoning.

That was worded verbatim from my letter of January 24, 1992. There was a reader response that led to a certain Pastor Friedrich Wilhelm Lucas, who had however been pastor in Gubin only up to 1929. I then learned from his housekeeper, then living in Remscheid, that from Gubin he had moved to Usedom (Baltic island). After the war, in 1946, he had buried Gerhart Hauptmann3› Reference on Hiddensee (another Baltic island).

These events were hazy in the memory of the readers of the Lausitzer Rundschau. It could hardly be otherwise after so long a time. After all, this Pastor Lucas had already been away from Gubin for 17 years at the time he presided at the burial of the great writer. This makes it all the more amazing that a few people even remembered the burial of a writer far from Gubin. A few even thought that Pastor Lucas had officiated at the burial of the Danish writer Martin Andersen Nexo, who had died in Dresden in 1954. This was all very exciting and very interesting, but it brought me no nearer to finding the Pastor L. I was looking for.

Old runs of Gubin newspapers were not to be found in Gubin. On the Polish side as well, the search was fruitless. In the Gubin of today, a barren field with a few stunted trees stands where the marketplace and town center used to be. Just beyond this there is a very lively black market, and only then does the town proper begin. I still had no answer from archives in Berlin (East or West) regarding any existing copies of Gubin newspapers. A birth announcement would have helped a lot. At least then the family name, of which only the initial letter “L” was known, would have been revealed.

On April 10, 1992, the Protestant Central Archive in Berlin wrote to me that, based on the pastoral almanac of the church province of Brandenburg of the year 1939, in 1938 no Pastor “L.” was active in Gubin. Thus in the entire Gubin area there was no Pastor L. to be found. How was that possible?

If G. was Gubin, then Pastor L. would not necessarily have to have been from Gubin, that is, he need not have been a pastor in Gubin. The registry office was then, as it is today, responsible for every child born in its district. The child had to be registered at the birthplace. G. was then the birthplace of Esther. That much was certain. The parents‘ place of residence, however, was still an open question. The family of the pastor could have been passing through, or perhaps they were visiting the wife‘s parents for the birth. Anything was possible. But then the birth would still have had to be registered in Gubin. If that were the case, then the search had to be broken off. Pastor L. could have come from any place in the German Reich. He was not to be found.

This is, if G. was Gubin. But was it really Gubin? How had I come to that conclusion? I had assumed that G. must lie in the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, and I had liberally identified that jurisdiction with the state of Brandenburg. But was that correct? It was unbelievably wrong – but more of that later.

I then took a step back in my search. Perhaps there was a chance to fill in some of the unknown quantities in the equation. If the Supreme Court decision had been published in other professional journals, perhaps there was more to read there. The content in such publications is often given in an abridged form. It might be possible to find information in another journal that had fallen by the wayside when the item was published in the Legal Weekly. In the library of my state court, I found a reference to two other publications: StAZ 38.464 and JFG 18.261.

StAZ stands for Zeitschrift fuer Standesamtswesen — The Bulletin for Registry Office Activities — which still exists today under the title The Registry Office. The publisher sent me a copy of its publication of the Esther decision in which there was a reference not to G., but to a place called W. At first I thought this was a typo in the transcription of the decision — W. instead of G., an easy mistake to make — now I know better. Here too I should have read the text more carefully, for it said the following:

Pastor L. in W. reported to the registry office that he had given the name ‘Esther’ to his daughter born August 11, 1938.

Pastor L. thus lived in W., and the responsible registry office could still have been in G. The combination of the two place-name initials didn’t help much. There remained the search suggested by the third publication: JFG. Those initials stood for the Jahrbuch fuer Rechtsprechung in der freiwilligen Gerichtsbarkeit – Yearbook of Legal Decisions in Civil Status Matters That was the breakthrough.

From this yearbook I could identify the two lower level jurisdictions of the district and state courts of Essen, a large industrial city in the Ruhr Valley, completely on the other end of the country from Gubin. Gubin, Lusatia, Brandenburg without Greater Berlin – all these had been dead ends. Hard to understand, even if I learned a lot from these detours. So – Essen it was. The two cities with a „G“ in the area of Essen, Gladbeck and Gelsenkirchen, each had their own district court.

A quick look at the text of the law, which would have been a smart thing to do earlier, gave me the answer. According to section 50 of the Civil Status Law, the district courts with authority in matters of civil status are those courts that are based in the same place as a state court. The district court in Essen was then responsible for the entire state court area of Essen.