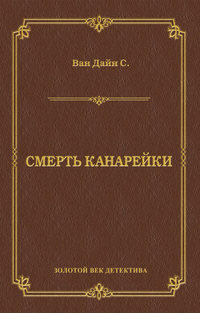

Полная версия

The «Canary» Murder Case / Смерть Канарейки. Книга для чтения на английском языке

“I couldn’t say, sir.”

“And when did Miss Odell tell you that she wanted you to come early this morning?”

“When I was leaving last night.”

“So she evidently didn’t anticipate any danger, or have any fear of her companion.”

“It doesn’t look that way.” The woman paused, as if considering. “No, I know she didn’t. She was in good spirits.”

Markham turned to Heath.

“Any other questions you want to ask, Sergeant?”

Heath removed an unlighted cigar from his mouth, and bent forward, resting his hands on his knees.

“What jewellery did this Odell woman have on last night?” he demanded gruffly.

The maid’s manner became cool and a bit haughty.

“Miss Odell”—she emphasized the “Miss,” by way of reproaching him for the disrespect implied in his omission—“wore all her rings, five or six of them, and three bracelets—one of square diamonds, one of rubies, and one of diamonds and emeralds. She also had on a sunburst of pear-shaped diamonds on a chain round her neck, and she carried a platinum lorgnette set with diamonds and pearls.”

“Did she own any other jewellery?”

“A few small pieces, maybe, but I’m not sure.”

“And did she keep ’em in a steel jewel-case in the bedroom?”

“Yes—when she wasn’t wearing them.” There was more than a suggestion of sarcasm in the reply.

“Oh, I thought maybe she kept ’em locked up when she had ’em on.” Heath’s antagonism had been aroused by the maid’s attitude; he could not have failed to note that she had consistently omitted the punctilious “sir” when answering him. He now stood up and pointed loweringly to the black document-box on the rosewood table.

“Ever see that before?”

The woman nodded indifferently. “Many times.”

“Where was it generally kept?”

“In that thing.” She indicated the Boule cabinet with a motion of the head.

“What was in the box?”

“How should I know?”

“You don’t know—huh?” Heath thrust out his jaw, but his bullying attitude had no effect upon the impassive maid.

“I’ve got no idea,” she replied calmly. “It was always kept locked, and I never saw Miss Odell open it.”

The Sergeant walked over to the door of the living-room closet.

“See that key?” he asked angrily.

Again the woman nodded; but this time I detected a look of mild astonishment in her eyes.

“Was that key always kept on the inside of the door?”

“No; it was always on the outside.”

Heath shot Vance a curious look. Then, after a moment’s frowning contemplation of the knob, he waved his hand to the detective who had brought the maid in.

“Take her back to the reception-room, Snitkin, and get a detailed description from her of all the Odell jewellery. … And keep her outside; I’ll want her again.”

When Snitkin and the maid had gone out, Vance lay back lazily on the davenport, where he had sat during the interview, and sent a spiral of cigarette smoke toward the ceiling.

“Rather illuminatin’, what?” he remarked. “The dusky demoiselle[27] got us considerably forrader. Now we know that the closet key is on the wrong side of the door, and that our fille de joie[28] went to the theatre with one of her favorite inamorati[29], who presumably brought her home shortly before she took her departure from this wicked world.”

“You think that’s helpful, do you?” Heath’s tone was contemptuously triumphant. “Wait till you hear the crazy story the telephone operator’s got to tell.”

“All right, Sergeant,” put in Markham impatiently. “Suppose we get on with the ordeal.”

“I’m going to suggest, Mr. Markham, that we question the janitor first. And I’ll show you why.” Heath went to the entrance door of the apartment, and opened it. “Look here for just a minute, sir.”

He stepped out into the main hall, and pointed down the little passageway on the left. It was about ten feet in length, and ran between the Odell apartment and the blank rear wall of the reception-room. At the end of it was a solid oak door which gave on the court at the side of the house.

“That door,” explained Heath, “is the only side or rear entrance to this building; and when that door is bolted nobody can get into the house except by the front entrance. You can’t even get into the building through the other apartments, for every window on this floor is barred. I checked up on that point as soon as I got here.”

He led the way back into the living-room.

“Now, after I’d looked over the situation this morning,” he went on, “I figured that our man had entered through that side door at the end of the passageway, and had slipped into this apartment without the night operator seeing him. So I tried the side door to see if it was open. But it was bolted on the inside—not locked, mind you, but bolted. And it wasn’t a slip-bolt, either, that could have been jimmied or worked open from the outside, but a tough old-fashioned turn-bolt of solid brass. … And now I want you to hear what the janitor’s got to say about it.”

Markham nodded acquiescence, and Heath called an order to one of the officers in the hall. A moment later a stolid, middle-aged German, with sullen features and high cheek-bones, stood before us. His jaw was clamped tight, and he shifted his eyes from one to the other of us suspiciously.

Heath straightway assumed the rôle of inquisitor.

“What time do you leave here at night?” He had, for some reason, assumed a belligerent manner.

“Six o’clock—sometimes earlier, sometimes later.” The man spoke in a surly monotone. He was obviously resentful at this unexpected intrusion upon his orderly routine.

“And what time do you get here in the morning?”

“Eight o’clock, regular.”

“What time did you go home last night?”

“About six—maybe quarter past.”

Heath paused and finally lighted the cigar on which he had been chewing at intervals during the past hour.

“Now, tell me about that side door,” he went on, with undiminished aggressiveness. “You told me you lock it every night before you leave—is that right?”

“Ja[30]—that’s right.” The man nodded his head affirmatively several times. “Only I don’t lock it—I bolt it.”

“All right, you bolt it, then.” As Heath talked his cigar bobbed up and down between his lips: smoke and words came simultaneously from his mouth, “And last night you bolted it as usual about six o’clock?”

“Maybe a quarter past,” the janitor amended, with Germanic precision.

“You’re sure you bolted it last night?” The question was almost ferocious.

“Ja, ja. Sure, I am. I do it every night. I never miss.”

The man’s earnestness left no doubt that the door in question had indeed been bolted on the inside at about six o’clock of the previous evening. Heath, however, belabored the point for several minutes, only to be reassured doggedly that the door had been bolted. At last the janitor was dismissed.

“Really, y’ know, Sergeant,” remarked Vance with an amused smile, “that honest Rheinlander bolted the door.”

“Sure, he did,” spluttered Heath; “and I found it still bolted this morning at quarter of eight. That’s just what messes things up so nice and pretty. If that door was bolted from six o’clock last evening until eight o’clock this morning, I’d appreciate having some one drive up in a hearse and tell me how the Canary’s little playmate got in here last night. And I’d also like to know how he got out.”

“Why not through the main entrance?” asked Markham. “It seems the only logical way left, according to your own findings.”

“That’s how I had it figured out, sir,” returned Heath. “But wait till you hear what the phone operator has to say.”

“And the phone operator’s post,” mused Vance, “is in the main hall half-way between the front door and this apartment. Therefore, the gentleman who caused all the disturbance hereabouts last night would have had to pass within a few feet of the operator both on arriving and departing—eh, what?”

“That’s it!” snapped Heath. “And, according to the operator, no such person came or went.”

Markham seemed to have absorbed some of Heath’s irritability.

“Get the fellow in here, and let me question him,” he ordered.

Heath obeyed with a kind of malicious alacrity.

Chapter VI. A Call for Help

(Tuesday, September 11; 11 a.m.)Jessup made a good impression from the moment he entered the room. He was a serious, determined-looking man in his early thirties, rugged and well built; and there was a squareness to his shoulders that carried a suggestion of military training. He walked with a decided limp—his right foot dragged perceptibly—and I noted that his left arm had been stiffened into a permanent arc, as if by an unreduced fracture of the elbow. He was quiet and reserved, and his eyes were steady and intelligent. Markham at once motioned him to a wicker chair beside the closet door, but he declined it, and stood before the District Attorney in a soldierly attitude of respectful attention. Markham opened the interrogation with several personal questions. It transpired that Jessup had been a sergeant in the World War,[31] had twice been seriously wounded, and had been invalided home shortly before the Armistice. He had held his present post of telephone operator for over a year.

“Now, Jessup,” continued Markham, “there are things connected with last night’s tragedy that you can tell us.”

“Yes, sir.” There was no doubt that this ex-soldier would tell us accurately anything he knew, and also that, if he had any doubt as to the correctness of his information, he would frankly say so. He possessed all the qualities of a careful and well-trained witness.

“First of all, what time did you come on duty last night?”

“At ten o’clock, sir.” There was no qualification to this blunt statement; one felt that Jessup would arrive punctually at whatever hour he was due. “It was my short shift. The day man and myself alternate in long and short shifts.”

“And did you see Miss Odell come in last night after the theatre?”

“Yes, sir. Every one who comes in has to pass the switchboard.”

“What time did she arrive?”

“It couldn’t have been more than a few minutes after eleven.”

“Was she alone?”

“No, sir. There was a gentleman with her.”

“Do you know who he was?”

“I don’t know his name, sir. But I have seen him several times before when he has called on Miss Odell.”

“You could describe him, I suppose.”

“Yes, sir. He’s tall and clean-shaven except for a very short gray moustache, and is about forty-five, I should say. He looks—if you understand me, sir—like a man of wealth and position.”

Markham nodded. “And now, tell me: did he accompany Miss Odell into her apartment, or did he go immediately away?”

“He went in with Miss Odell, and stayed about half an hour.”

Markham’s eyes brightened, and there was a suppressed eagerness in his next words.

“Then he arrived about eleven, and was alone with Miss Odell in her apartment until about half past eleven. You’re sure of these facts?”

“Yes, sir, that’s correct,” the man affirmed.

Markham paused and leaned forward.

“Now, Jessup, think carefully before answering: did any one else call on Miss Odell at any time last night?”

“No one, sir,” was the unhesitating reply.

“How can you be so sure?”

“I would have seen them, sir. They would have had to pass the switchboard in order to reach this apartment.”

“And don’t you ever leave the switchboard?” asked Markham.

“No, sir,” the man assured him vigorously, as if protesting against the implication that he would desert a post of duty. “When I want a drink of water, or go to the toilet, I use the little lavatory in the reception-room; but I always hold the door open and keep my eye on the switchboard in case the pilot-light should show up for a telephone call. Nobody could walk down the hall, even if I was in the lavatory, without my seeing them.”

One could well believe that the conscientious Jessup kept his eye at all times on the switchboard lest a call should flash and go unanswered. The man’s earnestness and reliability were obvious; and there was no doubt in any of our minds, I think, that if Miss Odell had had another visitor that night, Jessup would have known of it.

But Heath, with the thoroughness of his nature, rose quickly and stepped out into the main hall. In a moment he returned, looking troubled but satisfied.

“Right!” he nodded to Markham. “The lavatory door’s on a direct unobstructed line with the switchboard.”

Jessup took no notice of this verification of his statement, and stood, his eyes attentively on the District Attorney, awaiting any further questions that might be asked him. There was something both admirable and confidence-inspiring in his unruffled demeanor.

“What about last night?” resumed Markham. “Did you leave the switchboard often, or for long?”

“Just once, sir; and then only to go to the lavatory for a minute or two. But I watched the board the whole time.”

“And you’d be willing to state on oath that no one else called on Miss Odell from ten o’clock on, and that no one, except her escort, left her apartment after that hour?”

“Yes, sir, I would.”

He was plainly telling the truth, and Markham pondered several moments before proceeding.

“What about the side door?”

“That’s kept locked all night, sir. The janitor bolts it when he leaves, and unbolts it in the morning. I never touch it.”

Markham leaned back and turned to Heath.

“The testimony of the janitor and Jessup here,” he said, “seems to limit the situation pretty narrowly to Miss Odell’s escort. If, as seems reasonable to assume, the side door was bolted all night, and if no other caller came or went through the front door, it looks as if the man we wanted to find was the one who brought her home.”

Heath gave a short mirthless laugh.

“That would be fine, sir, if something else hadn’t happened around here last night.” Then, to Jessup: “Tell the District Attorney the rest of the story about this man.”

Markham looked toward the operator with expectant interest; and, Vance, lifting himself on one elbow, listened attentively.

Jessup spoke in a level voice, with the alert and careful manner of a soldier reporting to his superior officer.

“It was just this, sir. When the gentleman came out of Miss Odell’s apartment at about half past eleven, he stopped at the switchboard and asked me to get him a Yellow Taxicab. I put the call through, and while he was waiting for the car, Miss Odell screamed and called for help. The gentleman turned and rushed to the apartment door, and I followed quickly behind him. He knocked; but at first there was no answer. Then he knocked again, and at the same time called out to Miss Odell and asked her what was the matter. This time she answered. She said everything was all right, and told him to go home and not to worry. Then he walked back with me to the switchboard, remarking that he guessed Miss Odell must have fallen asleep and had a nightmare. We talked for a few minutes about the war, and then the taxicab came. He said good night, and went out, and I heard the car drive away.”

It was plain to see that this epilogue of the departure of Miss Odell’s anonymous escort completely upset Markham’s theory of the case. He looked down at the floor with a baffled expression, and smoked vigorously for several moments. At last he asked:

“How long was it after this man came out of the apartment that you heard Miss Odell scream?”

“About five minutes. I had put my connection through to the taxicab company, and it was a minute or so later that she screamed.”

“Was the man near the switchboard?”

“Yes, sir. In fact, he had one arm resting on it.”

“How many times did Miss Odell scream? And just what did she say when she called for help?”

“She screamed twice, and then cried ‘Help! Help!’”

“And when the man knocked on the door the second time, what did he say?”

“As near as I can recollect, sir, he said: ‘Open the door, Margaret! What’s the trouble?’”

“And can you remember her exact words when she answered him?”

Jessup hesitated, and frowned reflectively.

“As I recall, she said: ‘There’s nothing the matter. I’m sorry I screamed. Everything’s all right, so please go home, and don’t worry.’ … Of course, that may not be exactly what she said, but it was something very close to it.”

“You could hear her plainly through the door, then?”

“Oh, yes. These doors are not very thick.”

Markham rose, and began pacing meditatively. At length, halting in front of the operator, he asked another question:

“Did you hear any other suspicious sounds in this apartment after the man left?”

“Not a sound of any kind, sir,” Jessup declared. “Some one from outside the building, however, telephoned Miss Odell about ten minutes later, and a man’s voice answered from her apartment.”

“What’s this!” Markham spun round, and Heath sat up at attention, his eyes wide. “Tell me every detail of that call.”

Jessup complied unemotionally.

“About twenty minutes to twelve a trunk-light flashed on the board, and when I answered it, a man asked for Miss Odell. I plugged the connection through, and after a short wait the receiver was lifted from her phone—you can tell when a receiver’s taken off the hook, because the guide-light on the board goes out—and a man’s voice answered ‘Hello.’ I pulled the listening-in key over, and, of course, didn’t hear any more.”

There was silence in the apartment for several minutes. Then Vance, who had been watching Jessup closely during the interview, spoke.

“By the bye, Mr. Jessup,” he asked carelessly, “were you yourself, by any chance, a bit fascinated—let us say—by the charming Miss Odell?”

For the first time since entering the room the man appeared ill at ease. A dull flush overspread his cheeks.

“I thought she was a very beautiful lady,” he answered resolutely.

Markham gave Vance a look of disapproval, and then addressed himself abruptly to the operator.

“That will be all for the moment, Jessup.”

The man bowed stiffly and limped out.

“This case is becoming positively fascinatin’,” murmured Vance, relaxing once more upon the davenport.

“It’s comforting to know that some one’s enjoying it.” Markham’s tone was irritable. “And what, may I ask, was the object of your question concerning Jessup’s sentiments toward the dead woman?”

“Oh, just a vagrant notion struggling in my brain,” returned Vance. “And then, y’ know, a bit of boudoir racontage[32] always enlivens a situation, what?”

Heath, rousing himself from gloomy abstraction, spoke up.

“We’ve still got the finger-prints, Mr. Markham. And I’m thinking that they’re going to locate our man for us.”

“But even if Dubois does identify those prints,” said Markham, “we’ll have to show how the owner of them got into this place last night. He’ll claim, of course, they were made prior to the crime.”

“Well, it’s a sure thing,” declared Heath stubbornly, “that there was some man in here last night when Odell got back from the theatre, and that he was still here until after the other man left at half past eleven. The woman’s screams and the answering of that phone call at twenty minutes to twelve prove it. And since Doc Doremus said that the murder took place before midnight, there’s no getting away from the fact that the guy who was hiding in here did the job.”

“That appears incontrovertible,” agreed Markham. “And I’m inclined to think it was some one she knew. She probably screamed when he first revealed himself, and then, recognizing him, calmed down and told the other man out in the hall that nothing was the matter. … Later on he strangled her.”

“And, I might suggest,” added Vance, “that his place of hiding was that clothes-press.”

“Sure,” the Sergeant concurred. “But what’s bothering me is how he got in here. The day operator who was at the switchboard until ten last night told me that the man who called and took Odell out to dinner was the only visitor she had.”

Markham gave a grunt of exasperation.

“Bring the day man in here,” he ordered. “We’ve got to straighten this thing out. Somebody got in here last night, and before I leave I’m going to find out how it was done.”

Vance gave him a look of patronizing amusement.

“Y’ know, Markham,” he said, “I’m not blessed with the gift of psychic inspiration, but I have one of those strange, indescribable feelings, as the minor poets say, that if you really contemplate remaining in this bestrewn boudoir till you’ve discovered how the mysterious visitor gained admittance here last night, you’d do jolly well to send for your toilet access’ries and several changes of fresh linen—not to mention your pyjamas. The chap who engineered this little soirée[33] planned his entrance and exit most carefully and perspicaciously.”

Markham regarded Vance dubiously, but made no reply.

Chapter VII. A Nameless Visitor

(Tuesday, September 11; 11.15 a.m.)Heath had stepped out into the hall, and now returned with the day telephone operator, a sallow thin young man who, we learned, was named Spively. His almost black hair, which accentuated the pallor of his face, was sleeked back from his forehead with pomade; and he wore a very shallow moustache which barely extended beyond the alae of his nostrils. He was dressed in an exaggeratedly dapper fashion, in a dazzling chocolate-colored suit cut very close to his figure, a pair of cloth-topped buttoned shoes, and a pink shirt with a stiff turn-over collar to match. He appeared nervous, and immediately sat down in the wicker chair by the door, fingering the sharp creases of his trousers, and running the tip of his tongue over his lips.

Markham went straight to the point.

“I understand you were at the switchboard yesterday afternoon and last night until ten o’clock. Is that correct?”

Spively swallowed hard, and nodded his head. “Yes, sir.”

“What time did Miss Odell go out to dinner?”

“About seven o’clock. I’d just sent to the restaurant next door for some sandwiches—”

“Did she go alone?” Markham interrupted his explanation.

“No. A fella called for her.”

“Did you know this ‘fella’?”

“I’d seen him a couple of times calling on Miss Odell, but I didn’t know who he was.”

“What did he look like?” Markham’s question was uttered with hurried impatience.

Spively’s description of the girl’s escort tallied with Jessup’s description of the man who had accompanied her home, though Spively was more voluble and less precise than Jessup had been. Patently, Miss Odell had gone out at seven and returned at eleven with the same man.

“Now,” resumed Markham, putting an added stress on his words, “I want to know who else called on Miss Odell between the time she went out to dinner and ten o’clock when you left the switchboard.”

Spively was puzzled by the question, and his thin arched eyebrows lifted and contracted.

“I—don’t understand,” he stammered. “How could any one call on Miss Odell when she was out?”

“Some one evidently did,” said Markham. “And he got into her apartment, and was there when she returned at eleven.”

The youth’s eyes opened wide, and his lips fell apart.

“My God, sir!” he exclaimed. “So that’s how they murdered her!—laid in wait for her! …” He stopped abruptly, suddenly realizing his own proximity to the mysterious chain of events that had led up to the crime. “But nobody got into her apartment while I was on duty,” he blurted, with frightened emphasis. “Nobody! I never left the board from the time she went out until quitting time.”

“Couldn’t any one have come in the side door?”

“What! Was it unlocked?” Spively’s tone was startled. “It never is unlocked at night. The janitor bolts it when he leaves at six.”

“And you didn’t unbolt it last night for any purpose? Think!”

“No, sir, I didn’t!” He shook his head earnestly.

“And you are positive that no one got into the apartment through the front door after Miss Odell left?”

“Positive! I tell you I didn’t leave the board the whole time, and nobody could’ve got by me without my knowing it. There was only one person that called and asked for her—”

“Oh! So some one did call!” snapped Markham. “When was it? And what happened?—Jog your memory before you answer.”

“It wasn’t anything important,” the youth assured him, genuinely frightened. “Just a fella who came in and rang her bell and went right out again.”