Полная версия

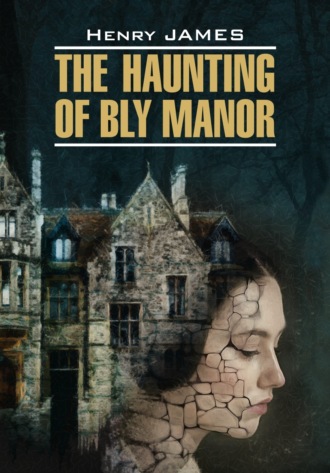

The Haunting of Bly Manor / Призраки усадьбы Блай. Книга для чтения на английском языке

This moment dated from an afternoon hour that I happened to spend in the grounds with the younger of my pupils alone. We had left Miles indoors, on the red cushion of a deep window seat; he had wished to finish a book, and I had been glad to encourage a purpose so laudable in a young man whose only defect was an occasional excess of the restless. His sister, on the contrary, had been alert to come out, and I strolled with her half an hour, seeking the shade, for the sun was still high and the day exceptionally warm. I was aware afresh, with her, as we went, of how, like her brother, she contrived—it was the charming thing in both children—to let me alone without appearing to drop me and to accompany me without appearing to surround. They were never importunate and yet never listless. My attention to them all really went to seeing them amuse themselves immensely without me: this was a spectacle they seemed actively to prepare and that engaged me as an active admirer. I walked in a world of their invention—they had no occasion whatever to draw upon mine; so that my time was taken only with being, for them, some remarkable person or thing that the game of the moment required and that was merely, thanks to my superior, my exalted stamp, a happy and highly distinguished sinecure. I forget what I was on the present occasion; I only remember that I was something very important and very quiet and that Flora was playing very hard. We were on the edge of the lake, and, as we had lately begun geography, the lake was the Sea of Azof.[61]

Suddenly, in these circumstances, I became aware that, on the other side of the Sea of Azof, we had an interested spectator.[62] The way this knowledge gathered in me was the strangest thing in the world—the strangest, that is, except the very much stranger in which it quickly merged itself. I had sat down with a piece of work—for I was something or other that could sit—on the old stone bench which overlooked the pond; and in this position I began to take in with certitude, and yet without direct vision, the presence, at a distance, of a third person. The old trees, the thick shrubbery, made a great and pleasant shade, but it was all suffused with the brightness of the hot, still hour. There was no ambiguity in anything; none whatever, at least, in the conviction I from one moment to another found myself forming as to what I should see straight before me and across the lake as a consequence of raising my eyes. They were attached at this juncture to the stitching in which I was engaged, and I can feel once more the spasm of my effort not to move them till I should so have steadied myself as to be able to make up my mind what to do. There was an alien object in view—a figure whose right of presence I instantly, passionately questioned. I recollect counting over perfectly the possibilities, reminding myself that nothing was more natural, for instance, then the appearance of one of the men about the place, or even of a messenger, a postman, or a tradesman’s boy, from the village. That reminder had as little effect on my practical certitude as I was conscious—still even without looking—of its having upon the character and attitude of our visitor. Nothing was more natural than that these things should be the other things that they absolutely were not.

Of the positive identity of the apparition I would assure myself as soon as the small clock of my courage should have ticked out the right second; meanwhile, with an effort that was already sharp enough, I transferred my eyes straight to little Flora, who, at the moment, was about ten yards away. My heart had stood still for an instant with the wonder and terror of the question whether she too would see; and I held my breath while I waited for what a cry from her, what some sudden innocent sign either of interest or of alarm, would tell me. I waited, but nothing came; then, in the first place—and there is something more dire in this, I feel, than in anything I have to relate—I was determined by a sense that, within a minute, all sounds from her had previously dropped; and, in the second, by the circumstance that, also within the minute, she had, in her play, turned her back to the water. This was her attitude when I at last looked at her—looked with the confirmed conviction that we were still, together, under direct personal notice. She had picked up a small flat piece of wood, which happened to have in it a little hole that had evidently suggested to her the idea of sticking in another fragment that might figure as a mast and make the thing a boat. This second morsel, as I watched her, she was very markedly and intently attempting to tighten in its place. My apprehension of what she was doing sustained me so that after some seconds I felt I was ready for more. Then I again shifted my eyes—I faced what I had to face.

VII

I got hold of Mrs. Grose as soon after this as I could; and I can give no intelligible account of how I fought out the interval.[63] Yet I still hear myself cry as I fairly threw myself into her arms: “They know—it’s too monstrous: they know, they know!”

“And what on earth—?” I felt her incredulity as she held me.

“Why, all that we know—and heaven knows what else besides!” Then, as she released me, I made it out to her, made it out perhaps only now with full coherency even to myself. “Two hours ago, in the garden”—I could scarce articulate—“Flora saw!”

Mrs. Grose took it as she might have taken a blow in the stomach. “She has told you?” she panted.

“Not a word—that’s the horror. She kept it to herself! The child of eight, that child!” Unutterable still, for me, was the stupefaction of it.

Mrs. Grose, of course, could only gape the wider. “Then how do you know?”

“I was there—I saw with my eyes: saw that she was perfectly aware.”

“Do you mean aware of him?”

“No—of her” I was conscious as I spoke that I looked prodigious things, for I got the slow reflection of them in my companion’s face. “Another person—this time; but a figure of quite as unmistakable horror and evil: a woman in black, pale and dreadful—with such an air also, and such a face!—on the other side of the lake. I was there with the child—quiet for the hour; and in the midst of it she came.”

“Came how—from where?”

“From where they come from! She just appeared and stood there—but not so near.”

“And without coming nearer?”

“Oh, for the effect and the feeling, she might have been as close as you!”

My friend, with an odd impulse, fell back a step. “Was she someone you’ve never seen?”

“Yes. But someone the child has. Someone you have.” Then, to show how I had thought it all out: “My predecessor—the one who died.”[64]

“Miss Jessel?”

“Miss Jessel. You don’t believe me?” I pressed.

She turned right and left in her distress. “How can you be sure?”

This drew from me, in the state of my nerves, a flash of impatience. “Then ask Flora—she’s sure!” But I had no sooner spoken than I caught myself up. “No, for God’s sake, don’t! She’ll say she isn’t—she’ll lie!”

Mrs. Grose was not too bewildered instinctively to protest. “Ah, how can you?”

“Because I’m clear. Flora doesn’t want me to know.”

“It’s only then to spare you.”

“No, no—there are depths, depths! The more I go over it, the more I see in it, and the more I see in it, the more I fear. I don’t know what I don’t see—what I don’t fear!”

Mrs. Grose tried to keep up with me. “You mean you’re afraid of seeing her again?”

“Oh, no; that’s nothing—now!” Then I explained. “It’s of not seeing her.”

But my companion only looked wan. “I don’t understand you.”

“Why, it’s that the child may keep it up—and that the child assuredly will—without my knowing it.”

At the image of this possibility Mrs. Grose for a moment collapsed, yet presently to pull herself together again, as if from the positive force of the sense of what, should we yield an inch, there would really be to give way to.[65] “Dear, dear—we must keep our heads! And after all, if she doesn’t mind it—!” She even tried a grim joke. “Perhaps she likes it!”

“Likes such things—a scrap of an infant!”

“Isn’t it just a proof of her blessed innocence?” my friend bravely inquired.

She brought me, for the instant, almost round.[66] “Oh, we must clutch at that—we must cling to it! If it isn’t a proof of what you say, it’s a proof of—God knows what! For the woman’s a horror of horrors.”

Mrs. Grose, at this, fixed her eyes a minute on the ground; then at last raising them, “Tell me how you know,” she said.

“Then you admit it’s what she was?” I cried.

“Tell me how you know,” my friend simply repeated.

“Know? By seeing her! By the way she looked.”

“At you, do you mean—so wickedly?”

“Dear me, no—I could have borne that. She gave me never a glance. She only fixed the child.”[67]

Mrs. Grose tried to see it. “Fixed her?”

“Ah, with such awful eyes!”

She stared at mine as if they might really have resembled them. “Do you mean of dislike?”

“God help us, no. Of something much worse.”

“Worse than dislike?”—this left her indeed at a loss.

“With a determination—indescribable. With a kind of fury of intention.”

I made her turn pale. “Intention?”

“To get hold of her.” Mrs. Grose—her eyes just lingering on mine—gave a shudder and walked to the window; and while she stood there looking out I completed my statement. “That’s what Flora knows.”

After a little she turned round. “The person was in black, you say?”

“In mourning—rather poor, almost shabby. But—yes—with extraordinary beauty.” I now recognized to what I had at last, stroke by stroke, brought the victim of my confidence, for she quite visibly weighed this. “Oh, handsome—very, very,” I insisted; “wonderfully handsome. But infamous.”

She slowly came back to me. “Miss Jessel—was infamous.” She once more took my hand in both her own, holding it as tight as if to fortify me against the increase of alarm I might draw from this disclosure. “They were both infamous,” she finally said.

So, for a little, we faced it once more together; and I found absolutely a degree of help in seeing it now so straight. “I appreciate,” I said, “the great decency of your not having hitherto spoken; but the time has certainly come to give me the whole thing.” She appeared to assent to this, but still only in silence; seeing which I went on: “I must have it now. Of what did she die? Come, there was something between them.”

“There was everything.”

“In spite of the difference—?”

“Oh, of their rank, their condition”—she brought it woefully out. “She was a lady.”

I turned it over; I again saw. “Yes—she was a lady.”

“And he so dreadfully below,” said Mrs. Grose.

I felt that I doubtless needn’t press too hard, in such company, on the place of a servant in the scale; but there was nothing to prevent an acceptance of my companion’s own measure of my predecessor’s abasement. There was a way to deal with that, and I dealt; the more readily for my full vision—on the evidence—of our employer’s late clever, good-looking “own” man; impudent, assured, spoiled, depraved. “The fellow was a hound.”[68]

Mrs. Grose considered as if it were perhaps a little a case for a sense of shades. “I’ve never seen one like him. He did what he wished.”

“With her?”

“With them all.”

It was as if now in my friend’s own eyes Miss Jessel had again appeared. I seemed at any rate, for an instant, to see their evocation of her as distinctly as I had seen her by the pond; and I brought out with decision: “It must have been also what she wished!”

Mrs. Grose’s face signified that it had been indeed, but she said at the same time: “Poor woman—she paid for it!”

“Then you do know what she died of?” I asked.

“No—I know nothing. I wanted not to know; I was glad enough I didn’t; and I thanked heaven she was well out of this!”

“Yet you had, then, your idea—”

“Of her real reason for leaving? Oh, yes—as to that. She couldn’t have stayed. Fancy it here—for a governess! And afterward I imagined—and I still imagine. And what I imagine is dreadful.”

“Not so dreadful as what I do,” I replied; on which I must have shown her—as I was indeed but too conscious—a front of miserable defeat. It brought out again all her compassion for me, and at the renewed touch of her kindness my power to resist broke down. I burst, as I had, the other time, made her burst, into tears; she took me to her motherly breast, and my lamentation overflowed. “I don’t do it!” I sobbed in despair; “I don’t save or shield them! It’s far worse than I dreamed—they’re lost!”[69]

VIII

What I had said to Mrs. Grose was true enough: there were in the matter I had put before her depths and possibilities that I lacked resolution to sound; so that when we met once more in the wonder of it we were of a common mind about the duty of resistance to extravagant fancies. We were to keep our heads if we should keep nothing else—difficult indeed as that might be in the face of what, in our prodigious experience, was least to be questioned. Late that night, while the house slept, we had another talk in my room, when she went all the way with me as to its being beyond doubt that I had seen exactly what I had seen. To hold her perfectly in the pinch of that, I found I had only to ask her how, if I had “made it up,” I came to be able to give, of each of the persons appearing to me, a picture disclosing, to the last detail, their special marks—a portrait on the exhibition of which she had instantly recognized and named them. She wished of course—small blame to her!—to sink the whole subject; and I was quick to assure her that my own interest in it had now violently taken the form of a search for the way to escape from it. I encountered her on the ground of a probability that with recurrence—for recurrence we took for granted—I should get used to my danger, distinctly professing that my personal exposure had suddenly become the least of my discomforts. It was my new suspicion that was intolerable; and yet even to this complication the later hours of the day had brought a little ease.

On leaving her, after my first outbreak, I had of course returned to my pupils, associating the right remedy for my dismay with that sense of their charm which I had already found to be a thing I could positively cultivate and which had never failed me yet. I had simply, in other words, plunged afresh into Flora’s special society and there become aware—it was almost a luxury!—that she could put her little conscious hand straight upon the spot that ached. She had looked at me in sweet speculation and then had accused me to my face of having “cried.” I had supposed I had brushed away the ugly signs: but I could literally—for the time, at all events—rejoice, under this fathomless charity, that they had not entirely disappeared. To gaze into the depths of blue of the child’s eyes and pronounce their loveliness a trick of premature cunning was to be guilty of a cynicism in preference to which I naturally preferred to abjure my judgment and, so far as might be, my agitation. I couldn’t abjure for merely wanting to, but I could repeat to Mrs. Grose—as I did there, over and over, in the small hours—that with their voices in the air, their pressure on one’s heart, and their fragrant faces against one’s cheek, everything fell to the ground but their incapacity and their beauty. It was a pity that, somehow, to settle this once for all, I had equally to re-enumerate the signs of subtlety that, in the afternoon, by the lake had made a miracle of my show of self-possession. It was a pity to be obliged to reinvestigate the certitude of the moment itself and repeat how it had come to me as a revelation that the inconceivable communion I then surprised was a matter, for either party, of habit. It was a pity that I should have had to quaver out again the reasons for my not having, in my delusion, so much as questioned that the little girl saw our visitant even as I actually saw Mrs. Grose herself, and that she wanted, by just so much as she did thus see, to make me suppose she didn’t, and at the same time, without showing anything, arrive at a guess as to whether I myself did! It was a pity that I needed once more to describe the portentous little activity by which she sought to divert my attention[70]—the perceptible increase of movement, the greater intensity of play, the singing, the gabbling of nonsense, and the invitation to romp.

Yet if I had not indulged, to prove there was nothing in it, in this review, I should have missed the two or three dim elements of comfort that still remained to me. I should not for instance have been able to asseverate to my friend that I was certain—which was so much to the good—that I at least had not betrayed myself. I should not have been prompted, by stress of need, by desperation of mind—I scarce know what to call it—to invoke such further aid to intelligence as might spring from pushing my colleague fairly to the wall. She had told me, bit by bit, under pressure, a great deal; but a small shifty spot on the wrong side of it all still sometimes brushed my brow like the wing of a bat; and I remember how on this occasion—for the sleeping house and the concentration alike of our danger and our watch seemed to help—I felt the importance of giving the last jerk to the curtain. “I don’t believe anything so horrible,” I recollect saying; “no, let us put it definitely, my dear, that I don’t. But if I did, you know, there’s a thing I should require now, just without sparing you the least bit more—oh, not a scrap, come!—to get out of you. What was it you had in mind when, in our distress, before Miles came back, over the letter from his school, you said, under my insistence, that you didn’t pretend for him that he had not literally ever been ‘bad’? He has not literally ‘ever,’ in these weeks that I myself have lived with him and so closely watched him; he has been an imperturbable little prodigy of delightful, lovable goodness. Therefore you might perfectly have made the claim for him if you had not, as it happened, seen an exception to take. What was your exception, and to what passage in your personal observation of him did you refer?”

It was a dreadfully austere inquiry, but levity was not our note, and, at any rate, before the gray dawn admonished us to separate I had got my answer. What my friend had had in mind proved to be immensely to the purpose. It was neither more nor less than the circumstance that for a period of several months Quint and the boy had been perpetually together. It was in fact the very appropriate truth that she had ventured to criticize the propriety, to hint at the incongruity, of so close an alliance, and even to go so far on the subject as a frank overture to Miss Jessel. Miss Jessel had, with a most strange manner, requested her to mind her business, and the good woman had, on this, directly approached little Miles. What she had said to him, since I pressed, was that she liked to see young gentlemen not forget their station.

I pressed again, of course, at this. “You reminded him that Quint was only a base menial?”

“As you might say! And it was his answer, for one thing, that was bad.”

“And for another thing?” I waited. “He repeated your words to Quint?”

“No, not that. It’s just what he wouldn’t!” she could still impress upon me. “I was sure, at any rate,” she added, “that he didn’t. But he denied certain occasions.”

“What occasions?”

“When they had been about together quite as if Quint were his tutor—and a very grand one—and Miss Jessel only for the little lady. When he had gone off with the fellow, I mean, and spent hours with him.”

“He then prevaricated about it—he said he hadn’t?” Her assent was clear enough to cause me to add in a moment: “I see. He lied.”

“Oh!” Mrs. Grose mumbled. This was a suggestion that it didn’t matter; which indeed she backed up by a further remark. “You see, after all, Miss Jessel didn’t mind. She didn’t forbid him.”

I considered. “Did he put that to you as a justification?”

At this she dropped again. “No, he never spoke of it.”

“Never mentioned her in connection with Quint?”

She saw, visibly flushing, where I was coming out. “Well, he didn’t show anything. He denied,” she repeated; “he denied.”

Lord, how I pressed her now! “So that you could see he knew what was between the two wretches?”

“I don’t know—I don’t know!” the poor woman groaned.

“You do know, you dear thing,” I replied; “only you haven’t my dreadful boldness of mind, and you keep back, out of timidity and modesty and delicacy, even the impression that, in the past, when you had, without my aid, to flounder about in silence, most of all made you miserable. But I shall get it out of you yet! There was something in the boy that suggested to you,” I continued, “that he covered and concealed their relation.”

“Oh, he couldn’t prevent—”

“Your learning the truth? I daresay! But, heavens,” I fell, with vehemence, athinking,[71] “what it shows that they must, to that extent, have succeeded in making of him!”

“Ah, nothing that’s not nice now!” Mrs. Grose lugubriously pleaded.

“I don’t wonder you looked queer,” I persisted, “when I mentioned to you the letter from his school!”

“I doubt if I looked as queer as you!” she retorted with homely force. “And if he was so bad then as that comes to, how is he such an angel now?”

“Yes, indeed—and if he was a fiend at school! How, how, how? Well,” I said in my torment, “you must put it to me again, but I shall not be able to tell you for some days. Only, put it to me again!” I cried in a way that made my friend stare. “There are directions in which I must not for the present let myself go.” Meanwhile I returned to her first example—the one to which she had just previously referred—of the boy’s happy capacity for an occasional slip. “If Quint—on your remonstrance at the time you speak of—was a base menial, one of the things Miles said to you, I find myself guessing, was that you were another.” Again her admission was so adequate that I continued: “And you forgave him that?”

“Wouldn’t you?”

“Oh, yes!” And we exchanged there, in the stillness, a sound of the oddest amusement. Then I went on: “At all events, while he was with the man—”

“Miss Flora was with the woman. It suited them all!”

It suited me, too, I felt, only too well; by which I mean that it suited exactly the particularly deadly view I was in the very act of forbidding myself to entertain. But I so far succeeded in checking the expression of this view that I will throw, just here, no further light on it than may be offered by the mention of my final observation to Mrs. Grose. “His having lied and been impudent are, I confess, less engaging specimens than I had hoped to have from you of the outbreak in him of the little natural man. Still,” I mused, “They must do, for they make me feel more than ever that I must watch.”

It made me blush, the next minute, to see in my friend’s face how much more unreservedly she had forgiven him than her anecdote struck me as presenting to my own tenderness an occasion for doing. This came out when, at the schoolroom door, she quitted me. “Surely you don’t accuse him—”

“Of carrying on an intercourse that he conceals from me? Ah, remember that, until further evidence, I now accuse nobody.” Then, before shutting her out to go, by another passage, to her own place, “I must just wait,” I wound up.

IX

I waited and waited, and the days, as they elapsed, took something from my consternation. A very few of them, in fact, passing, in constant sight of my pupils, without a fresh incident, sufficed to give to grievous fancies and even to odious memories a kind of brush of the sponge. I have spoken of the surrender to their extraordinary childish grace as a thing I could actively cultivate, and it may be imagined if I neglected now to address myself to this source for whatever it would yield. Stranger than I can express, certainly, was the effort to struggle against my new lights; it would doubtless have been, however, a greater tension still had it not been so frequently successful. I used to wonder how my little charges could help guessing that I thought strange things about them; and the circumstances that these things only made them more interesting was not by itself a direct aid to keeping them in the dark. I trembled lest they should see that they were so immensely more interesting. Putting things at the worst, at all events, as in meditation I so often did, any clouding of their innocence could only be—blameless and foredoomed as they were—a reason the more for taking risks. There were moments when, by an irresistible impulse, I found myself catching them up and pressing them to my heart. As soon as I had done so I used to say to myself: “What will they think of that? Doesn’t it betray too much?” It would have been easy to get into a sad, wild tangle about how much I might betray; but the real account, I feel, of the hours of peace that I could still enjoy was that the immediate charm of my companions was a beguilement still effective even under the shadow of the possibility that it was studied. For if it occurred to me that I might occasionally excite suspicion by the little outbreaks of my sharper passion for them, so too I remember wondering if I mightn’t see a queerness in the traceable increase of their own demonstrations.