полная версия

полная версияA Brief History of Forestry.

In the forests placed under the law, clearing and agricultural use is forbidden. Fellings and cultures must be made under direction of the Committee. No compensation is made for this limitation in use except where hygienic influence was the basis for placing the forest under ban.

If the regulations of the commissions had been observed to their full extent, all would have been well in time, but it is evident from subsequent legislative efforts that the execution of the laws was not what could be desired. Political exigencies required leniency in the application of the law. An interesting report on the results of the first quinquennium shows that during that time 170,000 acres were cleared, over 40,000 without permission, and by 1900, it was estimated, deforestation had taken place on about 5 million acres.

Wrangling over the classification of the lands under ban has continued until the present, and local authorities have continued to favor private as against public interest, to withdraw lands from the operation, and to wink at disregard of the law. Moreover, rights of user to dead wood, pasturage (goats are by law excluded) and other privileges continued to prevent improvement, although several laws to effect their extinction had been passed.

The devastating floods of 1882 led to much agitation, and, upon a report of a special commission in 1886, the law of 1874, which had obligated the communities to reforest their waste lands within five years or else to sell, was revived, extending the term of obligatory reforestation in the endangered sections to ten years. By that time, out of 800,000 acres originally declared as requiring reforestation, not more than 40,000 acres had been planted, but the acreage involved had also been gradually scaled down by the forest committees to 240,000 acres. The report, on the other hand, found that the area needing reboisement was at least 500,000 acres, requiring an expenditure of 12 million dollars. The law of 1877 did not contemplate enforced reforestation of banforests; it sought to accomplish this by empowering either the Department of Agriculture or the provinces or the communities or special associations to expropriate for the purpose of reforestation. Results were nil.

A revision and broadening of the law led to the general reboisement act of 1888,15 which has in view the correction of torrents, fixing of mountain slopes and sand dunes – one of the best laws of its kind in existence anywhere.

The principal features of the law are: obligatory reboisement of mountains and sand dunes according to plans, and under direction of the Department of Agriculture, the areas to be designated by the department, with approval or disapproval of the forest committees; contribution to the extent of two-fifths (finally raised to two-thirds) of the expense by the government; expropriation where owners do not consent, or fail to carry out the work as planned; right to reclaim property by payment of costs and interest, or else sale by government; right of the department to regulate and restrict pasture, but compensation to be paid to restricted owners; encouragement of co-operative planters’ associations. The area to be reforested was estimated at somewhat over 500,000 acres and the expense at over 7 million dollars.

The execution of the law was not any stricter than before. In 1900, the Secretary of Agriculture reports that “the laws do not yet receive effective application.” The difficulty of determining what is and what is not necessary to reforest, what is and what is not absolute forest soil made ostensibly the greatest trouble and occasioned delay, but financial incapacity and political influences bidding for popularity are probably the main cause of the inefficiency.

Meanwhile the forest department tried to promote reforestation by giving premiums from its scanty appropriation and distributing from its 130 acres of nurseries, during the years from 1867 to 1899, some 46 million plants and over 500 pounds of seed, and furnishing advice free of charge.

In 1897, again a commission was instituted to formulate new legislation. This commission reported in 1902, declaring that all accessible forests were more or less devastated, accentuating the needs of water management, and proposing a more rigorous definition of ban forests, a strict supervision of communal forests, and the management of private properties under working plans by accredited foresters or else under direct control of the forest department, the foresters to be paid by the State, which is to recover from the owners. It was found that in the past 35 years of the 125,000 acres needing reforestation urgently only 58,300 acres had been planted at an expense of $1,340,000.

In 1910, conditions seem not to have much improved, for again a vigorous attempt at re-organization and improvement on the law of 1877 was made by the Minister of Agriculture; so far without result.

It is to be noted that Italy is perhaps the only country where forest influence on health conditions was legally recognized, by the laws of 1877 and 1888. The belief that deforestation of the maremnae, the marshy lowlands between Pisa and Naples, had produced the malarial fever which is rampant here, led the Trappist monks of the cloister at Tre Fontane to make plantations of Eucalyptus (84,000) beginning in 1870, the State assisting by cessions of land for the purpose. A commission, appointed to investigate the results, in 1881, threw doubt on the effectiveness of the plantation, finding the observed change in health conditions due to improvement of drainage; and lately, the mosquito has been recognized as the main agency in propagating the fever. The new propositions, however, did not any more recognize this claimed influence as a reason for public intervention. Incidentally it may be stated that to two Italians is due the credit of having found the true cause of salubriousness of forest air, namely in the absence of pathogenic bacteria.

3. Education and Literature

The first forest school was organized by Balestrieri, who had studied in Germany, at the Agricultural School near Turin about 1848, transferred to the Technical Institute in Turin in 1851. This school continued until 1869, and from 1863 on, had been recognized by the State, assuring its graduates employment in State service. In 1869, the State established a forest school of its own (Institute Forestale) at Vallambrosa near Florence, with a three years’ course (since 1886, four years) and, in 1900, with eleven professors and 40 students. In spite of the State subvention of $8,500, it appears that some peculiar economies are necessary, for owing to the absence of stoves the school is closed from Nov. 1 to March 1. In spite of the existence of this school, the State Service is recruited also from men who have not passed through this school.

The legislative propositions brought forward in 1910 also provide for transfer of this school to Florence, leaving only the experiment station in Vallambrosa, and also for raising the standard of instruction. At the same time, however, there was at the old institution ordered a “rush course” to be finished in 15 months, since it appeared that not enough foresters were in existence to carry out the proposed re-organization.

In 1905, a school of silviculture for forest guards was instituted in Cittaducale, the course being 9 months.

Besides the technical school at Vallambrosa, agricultural schools have chairs of forestry or arboriculture, as for instance the Royal school at Portici. As an educational feature, the introduction of Arbor Day, in 1902, la festa dei alberi, should also be mentioned.

The existence of a forest school naturally produces a literature. While a considerable number of popular booklets attempt the education of the people, who are the owners of the forest, there is no absence of professional works. Among these should be mentioned Di Berenger’s Selvicoltura, a very complete work, which also contains a brief history of forestry in the Orient, Greece and Italy. G. Carlos Siemoni’s Manuele d’arte forestale (1864), and the earlier Scienza selvana by Tondi (1829) are encyclopedias of inferior quality.

In 1859, R. Maffei, a private forester, began to publish the Revista forestale del regno d’ Italia, an annual review, for the purpose of popularizing forestry in Italy, afterwards changed into a monthly, which continued for some time under subventions from the government.

A number of propagandist forestry associations were formed at various times, publishing leaflets or journals, one of these L’Alpe, a monthly, in 1902. In 1910, the two leading societies combined into a federation Pro montibus ed enti affini, merging also the Rivista forestale italiana with L’Alpe, which serves both propagandist and professional needs.

SPAIN

Revista de Montes, a semi-official journal, established in 1877, is the best source.

El Manuel de Legislacion y Administracion Forestal, by Hilario Ruiz, and Novisima Legislacion Forestal, by Del Campo, 1901, elaborate the complicated legislation up to 1894.

Dicionaro Hispano-Americano, 1893, contains an article (montes) on the administrative practice of the forest laws.

A Year in Spain, by a young American (Slidell) 1829, gives an excellent account of physical conditions of the country and character of the people at that time.

Das Moderne Geistesleben in Spanien, 1883, and Kulturgeschichtliche und Wirtschaftspolitische Betrachtungen, 1901, by Gustav Dierks, details character of institutions and people.

“Poor Spain” is the expression which comes to the lips of everybody who contemplates the economic conditions of this once so powerful nation, almost the ruler of the world. Once, under the beneficent dominion of the Saracens, a paradise where, as a Roman author puts it, “Nil otiosum, nihil sterile in Hispania,” it has become almost a desert through neglect, indolence, ignorance, false pride, lack of communal spirit, despotism of church, and misrule by a corrupt bureaucracy.

With the exception of a narrow belt along the seashore, the whole of the Iberian peninsula is a vast high mesa, plateau or tableland, 1,500 to 3,000 feet above sea level, traversed by lofty mountain chains, or sierras, five or six in number, running parallel to each other, mainly in a westerly and southwesterly direction. These divide the plateau into as many plains, treeless, and for the most part, arid, exposed to cold blasts in winter, and burning up in summer. They are frequently subjected to severe droughts, which sometimes have lasted for months, bringing desolation to country and people. The rivers, as they usually do in such countries similar to our arid plains, form cañons and arroyos, and, being uncertain in their water stages, none of them are navigable although hundreds of miles long, but useful for irrigation, on which agriculture relies. The great mineral wealth had made Spain the California of the Carthaginians and Romans, and it is still its most valuable resource.

Spain awakened to civilization through the visits of Phoenicians and Carthaginians followed by the Romans. During the first centuries of the Christian era there occurred one of the several periods of extreme prosperity, when a supposed population of 40 million exploited the country. After the dark days of the Gothic domination, a second period of prosperity was attained for the portion which came under the sway of the industrious and intelligent Moors or Saracens (711 to 1,000 A.D.) who made the desert bloom, and whose irrigation works are still the mainstay of agriculture at present. Centuries of warfare and carnage to re-establish Christian kingdoms still left the country rich, when, in 1479, the several kingdoms were united into one under Ferdinand and Isabella, and the Moors were finally driven out altogether (1492). This kingdom persisted in the same form to the present time with only a short period as a republic (1873). Spain was among the first countries to have a constitution.

After the Conquest of the Moors, and with the discovery of America, again a period of prosperity set in for the then 20 million people, but, through oppression by State and Church (Inquisition), which also led to the expulsion of the Jews and large emigration to America, the prosperity of the country was destroyed, the population reduced to 10 million in 1800, and the conditions of character and government created which are the cause of its present desolation. Since the beginning of the century, the population has increased to near 18 million, but financial bankruptcy keeps the government inefficient and unable to accomplish reforms even if the people would let it have its way.

1. Forest Conditions

It has been a matter of speculation whether Spain was, or was not, once heavily wooded (see page 11). In Roman times, only the Province of La Manca is reported as being unforested, and, in the 13th and 14th centuries, extensive forest zones are still recorded. The character of the country at present, and the climate, both resembling so much our own arid plains, make it questionable to what extent the forest descended from the mountain ranges, which were undoubtedly well wooded.

At present the forest is mainly confined to the higher mountains. The best is to be found in the Pyrenees and their continuation, the Cantabrian mountains.

The area of actual forest (bosques) is not known with precision, since in the official figures mere potential forest, i.e., brush and waste land, is included (montes), and the area varies, i.e., diminishes through new clearings, of which the statistics do not keep account. Moreover, the statistics refer only to the “public forests,” leaving out the statement of private forest areas, if any.

In 1859, this area was reported as over 25 million acres or 20 per cent. of the land area (196,000 square miles); in 1885, the acreage had been reduced to about 17.5 million acres; and, in 1900, about 16 million acres, or 13 per cent. of the land area remained as public forest, and the total was estimated at somewhat over 20 million acres.

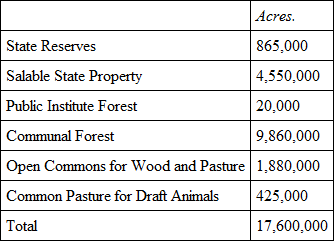

The following peculiar classification, published in 1874, gives (in round figures) at once an insight into the meaning of montes, and the probable condition of the “public forest” area:

An estimate of the actual forest (timber and coppice), does not exceed 12 million acres for a population of 18 million, or .7 acres per capita. The latest official figures claim as State property around 600,000 acres, and municipal institutional property 11.5 million acres; these constituting the public forests. According to official classification, these public forests are to the extent of 5.3 million acres high forest, 3 million coppice, the balance brushwoods.

In spite of this evident lack of wood material, except for firewood or charcoal, the importations in 1903 did not exceed 13.5 million dollars, accentuating the absence of industrial development. The official statement of imports reports 6.5 million dollars more than the above figure, but this includes horses and cattle enumerated as forest products – products of the “montes.” These also figure in the exportations of 15 million dollars, which to the extent of one-half consists of cork (some 5 million dollars from 630,000 acres) and tanbark, while chestnuts, filberts and esparto furnish the balance. In 1908, the imports of lumber and staves alone amounted to $7,382,000.

In 1882, all the public forests produced from wood sales only $900,000, but the value of the products taken by rights of user was estimated at nearly twice that amount. In 1910, the average income of the forest service was reported as having averaged for the decade in the neighborhood of 2 million dollars, and the expense approximately 1 million, a net yield of about 30 cents per acre on the area involved resulting, the total cut being 5.7 million cubic feet annually.

The forest flora and its distribution is very similar to that of Italy, and is described fully in two volumes prepared by a special commission appointed for this purpose.

2. Development of Forest Policy

Spain is noted for its comprehensive legislation without execution; it is also known that official reports are rarely trustworthy, so that what appears on paper is by no means always found in reality, hence all statements must be accepted with reservations.

The forest laws of Spain are somewhat similar to those of Italy, yet show less appreciation of the needs of technical forest culture. The value of forest resources and need of economy in their use was, indeed, recognized early. Recommendations for their conservative use are recorded from the 13th century on. An ordinance of Pedro I, in 1351, imposed heavy fines upon forest destroyers. Ferdinand V, in 1496, expressed alarm at the progressing devastation, and, in 1518, we find a system of forest guards established, and even ordinances ordering reforestation of waste lands, which were again and again repeated during the century. In 1567 and 1582, notes of alarm at the continuing destruction prove that these ordinances had no effect. The same complaints and fears are expressed by the rulers during the 17th and 18th centuries, without any effective action. In 1748, Ferdinand VI placed all forests under government supervision, but in 1812, the Cortes of Cadiz, under the influence of the spirit of the French Revolution, rescinded these orders and abolished all restrictions.

An awakening to the absolute necessity of action seems not to have arrived until about 1833, when a law was enacted and an ordinance issued, at great length defining the meaning of “montes,” and instituting in the Corps of Civil Engineers a forest inspection. At the same time, a special school was to be established in Madrid. This last proposition does not seem to have materialized, for, in 1840, we find that several young men were sent to the forest school at Tharandt (Germany).

No doubt, under the influence of these men on their return, backed by La Sociedad Economica of Madrid, a commission to formulate a forest law was instituted in 1846, and in the same year, carrying out ordinances of 1835 and 1843, a forest school was established at Villaviciosa de Odon, later (1869) transferred to the Escurial near Madrid. This school, under semi-military organization, first with a three-year, later a four-year, course, and continually improved and enlarged in its curriculum (one Director and 13 professors in 1900), is the pride of the Spanish foresters, to all appearances deservedly so. It was organized after German models by Bernardo della Torre Royas as first Director.

The creation of a forest department, however, Cuerpo de Montes, had to wait until 1853. This department, under the Minister of Public Works (now under the Minister of Agriculture), is a close corporation made up of the graduates of the school as Ingenieros de Montes, acceptance into which is based upon graduation and four years’ service in the forest department as assistants besides the performance of some meritorious work. The school stands in close relation to the department service.

The first work of the new administration was a general forest survey to ascertain conditions, and especially to determine which of the public forests, under the laws of 1855 and 1859, it was desirable to retain. The investigation showed that there was more forest (defined as in the above classification) than had been supposed, but that it was in even worse condition than had been known. The public forests, i.e., those owned by the State, the communities and public institutions, were divided into three classes according to the species by which formed, which was the easiest way of determining their location as regards altitude, and their public value; namely, the coniferous forest and deciduous oak and chestnut forests, which were declared inalienable; the forests of ash, alder, willow, etc., naturally located in the lower levels, therefore without interest to the state, which were declared salable; and an intermediate third class composed of cork oak and evergreen oak, whose status as to propriety of sale was left in doubt. In 1862, a revision of this classification left out this doubtful class, adding it and the forest areas of the first class which were not at least 250 acres in extent to the salable property. The first class, which was to be reserved, was found to comprise nearly 17 million acres (of which 1.2 million was owned by the State), while the salable property was found to be about half that area.

Ever since, a constant wrangle and commotion has been kept up regarding the classification, and repeated attempts, sometimes successful, have been made by one faction, usually led by the Minister of Finance, to reduce the public forest area (desamortizadoro), opposed by another faction under the lead of the forest administration, which was forced again and again to re-classify. In 1883, the alienable public forest area was by decree placed under the Minister of Finance, the inalienable part remaining under the Minister of Public Works (Fomento); very much the same as it was in the United States until recently. The public debt and immediate financial needs of the corporations gave the incentive for desiring the disposal of forest property, and, to satisfy this demand, it was ordered, in 1878, that all receipts from the State property and 20 per cent. of the receipts from communal forests were to be applied towards the extinguishment of the debt.

The ups and downs in this struggle to keep the public forests intact were accentuated on the one hand by the pressing needs of taking care of the debt, on the other hand by drought and flood. Thus, in 1874, the sale in annual instalments of over 4.5 million acres in the hands of the Minister of Finance was ordered, but the floods of the same year were so disastrous, (causing 7 million dollars damage, 760 deaths, 28,000 homeless), being followed by successive droughts, that a reversion of sentiment was experienced, which led to the enactment of a reboisement law in 1877. This law, having in view better management of communal properties, ordered with all sorts of unnecessary technical details, the immediate reforestation of all waste land in the public forests, creating for that purpose a corps of 400 cultivators (capatacas de cultivos). To furnish the funds for this work the communities were to contribute 10 per cent. of the value of the forest products they sold or were entitled to. But funds were not forthcoming, and, by 1895, under this law only 21,000 acres had been reforested (three-fourths by sowing).

The financial results of the management of the public forests, although the forest department probably did the best it could under the circumstances, had, indeed, not been reassuring. In 1861, a deficit of $26,000 was recorded; in 1870, $600,000 worth of material was sold, 1.3 million dollars worth given away, and $700,000 worth destroyed. Altogether, by fire and theft, it was estimated that 15 per cent. of the production was lost. In 1885, this loss was estimated at 25 per cent., when the net income had attained to 15 cents per acre, or, on the 17.5 million acres to less than three million dollars.

When it is considered that the governors of provinces and their appointees, besides the village authorities, had also a hand in the administration, it is no wonder that the forest department was pretty nearly helpless. While, under the law of 1863, the department was specially ordered to regulate the management of communal forests and to gauge the cut to the increment, the political elements in the administration, which appointed the forest guards, made the regulations mostly nugatory.

At last, in 1900, a new era seems to have arrived, a thorough reorganization was made, which lends hope for a better future. The technical administration was divorced from the political influence and placed under the newly created Minister of Agriculture. The machinery of the Cuerpo de Montes was remodeled. This consists now of one Chief Inspector-General, four Division Chiefs, ten Inspectors-General for field inspection, 50 chief engineers of district managers, 185 assistants, and 342 foresters and guards, the latter now appointed by the department, instead of the Governors, and not all, as formerly, chosen from veteran soldiers. The better financial showing referred to above was the result.