полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

A Chronicle History of the Life and Work of William Shakespeare

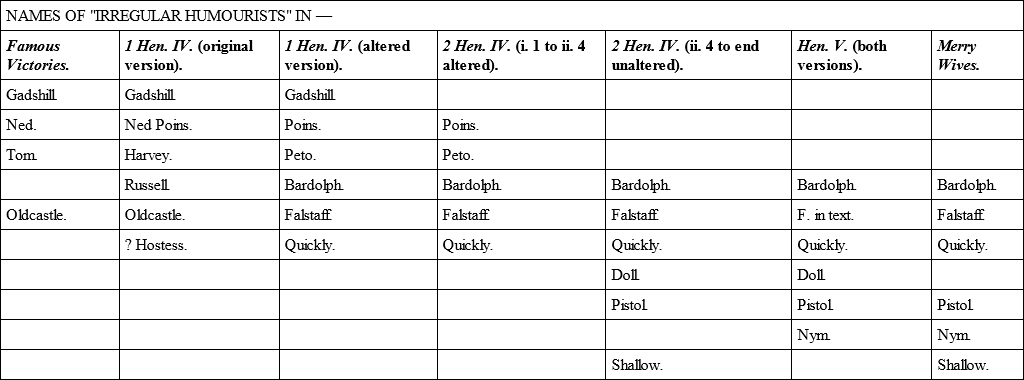

Henry V. was acted, with the choruses as we have them in the Folio, between 15th April and 28th September, while Essex was in Ireland; see chorus to Act v. That this was the final revision of the play, I am by no means convinced. The scene with the Scotch and Irish captains, iii. 2. 69 to end, I take to be an insertion for the Court performance, Christmas 1605, to please King James, who had been so annoyed that year by depreciation of the Scots on the stage. That the Quarto copy is printed from an abridged version made for acting purposes, is palpable. By omitting i. 1, and substituting one Bishop for two in i. 2 (two being retained in the stage direction) Ely is disposed of; by simple omission and transference of a speech in iv. 3 to Warwick, Westmoreland disappears; in a similar way Bedford gives place to Clarence; in iv. 3. 69 Salisbury is replaced by Gloster, and was evidently meant to be in l. 5-9 of the same scene; in iv. 1 Erpingham remains in the stage direction, but has been cut out in the text. That the version from which the Quarto was abridged was the 1599 copy, is a separate question to which I am inclined to say no. I rather hold that it was an earlier one without choruses, and following the Chronicle historians much more closely. I cannot otherwise account for the substitution of Gebon for Rambures in iii. 7, and iv. 5; and of Bourbon for Britany in iii. 5, and for Dolphin in iii. 7, iv. 5. Mr. Daniel's theory is that the Quarto was later than the Folio version, that is to say, that Shakespeare wrote a play historically incorrect, that his errors were corrected in a stage version before 1600, i. e., while he was still himself an actor; that the errors were afterwards restored, and have kept the stage ever since. I cannot think this. I believe that the Quarto is (as we have seen in other instances) a shortened version of a play written early in 1598 for the Curtain Theatre, and that the Folio (except such alterations as were made after James's accession) is a version enlarged and improved for the Globe Theatre later in the same year. With regard to this series of Falstaff plays, the following table may be of interest.

According to my hypothesis, the original names Oldcastle, Ned Poins, Gadshill, &c., were chiefly taken from The Famous Victories of Henry V.; all these disappear from the series by ii. 4 of 2 Henry IV.: the later names, Bardolph, Falstaff, Nym, Pistol, Shallow, persist to the end of the series, but did not occur in the original forms of 1 and 2 Henry IV. The name Falstaff was no doubt taken from 1 Henry VI., in which Shakespeare had been writing on March 1592, and which we know from the Epilogue to Henry V. to have been revived by 1598 at latest.

1599As You Like It was "stayed" on the 4th August 1600, and was written after "Diana in the fountain" (iv. 1. 154) was set up in Cheapside in 1598 (Stow). In iii. 5. 83 a line is quoted from Hero and Leander, published in 1598; the only instance in which Shakespeare directly refers to a contemporary poet. The date may, I think, be still more exactly fixed from i. 2. 94, "the little wit that fools have was silenced," which alludes probably to the burning of satirical books by public authority 1st June 1599. Every indication points to the latter part of 1599 as the date of production. This play is a rival to the Robin Hood plays acted at the Rose in 1598; Jaques, "the traveller," seems to have been the origin of Jonson's Amorphus in Cynthia's Revels, and Touchstone of Cos the whetstone in the same play; compare i. 2. 56. The female characters differed considerably in height, as in Much Ado and The Dream. The remarks of Touchstone on quarrels and lies in v. 4 should be compared with Love's Labour's Lost, i. 2 to end; Romeo and Juliet, ii. 4. 26, &c. The comparison of the world to a stage in ii. 7 suggests a date subsequent to the building of the Globe, with its motto of Totus mundus agit histrionem; and the introduction of a fool proper, in place of a comic clown such as is found in all the anterior comedies, confirms this: the "fools" only occur in plays subsequent to Kempe's leaving the company. The title is taken from Lodge's address prefixed to his Rosalynde, on which the play is founded – "if you like it, so," says Lodge – and it is alluded to in the Epilogue (which, like that to 2 Henry IV., is spoken by a female character), and again by Jonson in the Epilogue to Cynthia's Revels, which play has much more connection with the present than is usually supposed. There is a tradition that Shakespeare took the part of Adam.

1600The Merry Wives of Windsor, as we have it in the Folio, was probably made for the Court performance in February 1600; in i. 4, the "King's English" does not imply that James, not Elizabeth, was on the throne; but that the time of action is under a king, Henry IV. It was written after Henry V.; perhaps, according to the old tradition, in obedience to the Queen's command, who wished to see Falstaff in love, Shakespeare not having fulfilled his promise in the Epilogue to 2 Henry IV. to introduce him in the Henry V. play; a failure probably caused by the defection at this date of the actor who had taken this part – Kempe, Beeston, Duke, and Pallant having quitted the King's men between the production of 2 Henry IV. and that of this play. The title, The Merry Wives of Windsor, suggests approximation in subject with The Merry Devil of Edmonton (1597), and so does the great likeness in the characteristics in the Hosts of these plays; while the plot of the Anne Page story is identical with that of Wily Beguiled (1597), Fenton corresponding to Sophos, Caius to Churms, Simple to Plodall, Evans to R. Goodfellow. It appears from the Quarto edition that Ford's assumed name was originally Brook, not Broome. This was probably altered because Brook was the name of the Lord Cobham, who took offence at the production of Oldcastle on the stage. The song of Marlowe's sung by Evans in iii. 1 was published as Shakespeare's in the Passionate Pilgrim in 1599; not necessarily by any means in consequence of its previous introduction in this play. Mr. P. A. Daniel has rightly pointed out that iii. 5 is really composed of two scenes, one between Falstaff and Quickly, the other between Falstaff and Ford; and that the latter ought to begin the fourth Act: he has also shown that in various places the Folio has inconsistencies not explicable without the aid of the Quarto. But all this does not prove any "degradation" of the play at "managerial" hands; it rather indicates hurried and careless production, such as we might expect in a play ordered to be produced in a fortnight, according to the old tradition. Another internal proof of such hurry, both in this play and in Much Ado about Nothing, lies in the fact that they are almost entirely in prose; which is not the case in any other play by Shakespeare. And this brings us to the question of the nature of the Quarto version. It has been held to be merely a first sketch of the play: this theory is untenable. Mr. P. A. Daniel holds it to be a stolen version made up by a literary hack from shorthand notes obtained at a representation. This hypothesis gives no explanation of the "cousin-Garmombles" of iii. 5, nor does it enable us to understand how no better a representation of the play was issued, nor how whole scenes (that of the fairies for example) appear in quite a different version from the Folio. My own opinion is that the case is parallel to that of Romeo and Juliet; that the Quarto is printed from a partly revised prompter's copy of the older version of the play, which became useless when Shakespeare had made his final version. I believe also that this older version was produced soon after the visit of the Count of Mümplegart (Garmombles) to Windsor in August 1592; that it was probably the Jealous Comedy, acted as a new play by Shakespeare's company 5th January 1593; that when Shakespeare revived this old play, he accommodated the characters to Henry IV. as best he could. Mr. Daniel's argument that The Merry Wives was a later play than Henry V., because Nym would otherwise have had no title to special mention in the title-page of the Quarto, has not much weight. This Quarto was printed three years after Henry V. was produced, and Nym's reputation from either play was three years old, according to Mr. Daniel himself. Why then should he not be mentioned?

I must add a word on the Fairy scene, v. 5. The fairies are Nan the Queen (in red?), cf. iv. 4. 71; Will Cricket (in grey?); two other boys, Bede and Bean, in green and white; and Evans, Puck Hobgoblin or Robin Goodfellow, in black. The prefixes Qu., Qui., and Pist. are mistakes for Queen and Puck. Pistol and Quickly cannot be actors in this scene, nor in the entrance are they placed with "Evans, Anne Page, Fairies," but at the ends of the second and third lines, as if by afterthought. All the Pistol fairy speeches belong to Evans (Puck). There seems to have arisen some confusion in the final revision, when this scene was probably altered. Further confirmation of the original early date of the play may be found in Falstaff's statement that the Thames shore was "shelvy and shallow" (iii. 5. 15); for in 1592 the Thames was so low as to be fordable at London Bridge, and Falstaff was thrown in the ford at Datchet. But the allusions to "three Doctor Faustuses" and Mephistopheles are not helpful; Faustus was on the boards till 1597 at least. One of Henry Julius' plays derived from English sources, printed in 1594, The Adulteress, contains the same story as The Merry Wives. If this was not derived from Shakespeare's play, whence was it? The ground of the English play was probably the story in Tarleton's News out of Purgatory (1590). Note that the other play by Julius distinctly traceable in origin to the English stage is Vincentius Ladislaus (1594), in which the similarities to Much Ado (1590), are as marked as in the present instance. We have already seen that Evans acts the part of Robin Goodfellow, and that Will Cricket is another fairy; but these are two characters in Wily Beguiled, in which play Robin Goodfellow means Drayton and Will Cricket Kempe. I believe that in Shakespeare's play, Evans and Dr. Caius are satirical representations of Drayton and Lodge. Drayton is introduced as Evan, a Welsh attorney, by Jonson in For the Honour of Wales, and Lodge was frequently satirised on the stage as a French doctor. The part of Falstaff was acted in Charles the First's time by Lowin, and there is no reason why he should not have been the original performer of it in this play as revised. He was twenty-four years old in 1600.

1600Julius Cæsar is alluded to in Weever's Mirror of Martyrs (Sir John Oldcastle), 1601; and the actor of Polonius in Hamlet iii. 2. 109 had probably acted the part of Cæsar; at any rate Cæsar must be anterior to the Quarto Hamlet which was produced in 1601. The structure of this play is remarkable; the first three acts and last two have no characters in common except Brutus, Cassius, Antony, and Lucius; there are in fact two plays in one, Cæsar's Tragedy and Cæsar's Revenge. Contemporary plays by other dramatists were produced in a double pattern: e. g., Marston's Antonio and Mellida, in two parts; Chapman's Bussy d'Ambois, in two parts; Kyd's old play of Jeronymo, in two parts. All these were on the stage at the same time as Julius Cæsar. Revenge-plays with ghosts in them were the rage for the next four years. That the present play has been greatly shortened, is shown by the singularly large number of instances in which mute characters are on the stage; which is totally at variance with Shakespeare's usual practice. The large number of incomplete lines in every possible position, even in the middle of speeches, confirms this. That alterations were made we have the positive testimony of Jonson, who in his Discoveries tells us that Shakespeare wrote, "Cæsar did never wrong but with just cause" (compare iii. 1. 47). That this original reading stood in the acting copies till not long before the 1623 Folio was printed, is clear from the fact that Jonson, in the Induction to his Staple of News (1625), alludes to it as a well-known line requiring no explanation – "Cry you mercy," says Prologue, "you never did wrong but with just cause." This would imply that Shakespeare did not make the alterations himself; a hypothesis confirmed by the spelling of Antony without an h: this name occurs in eight of Shakespeare's plays, and in every instance but this invariably is spelled Anthony. Jonson himself is more likely to have been called on to make this revision than any other author connected with the King's company c. 1622. The "et tu Brute" about which so much has been written was probably taken from Jonson's Every Man out of his Humour (i. 1); it is found in the Duke of York (1595) and elsewhere. Nicholson, in his Acolastus his after wit (S. R. 8th September 1600), probably took it from Shakespeare's play, "Et tu Brute! wilt thou stab Cæsar too?"

1601All's Well that Ends Well manifestly contains passages – i. 1. 230-244; i. 3. 130-142; ii. 1. 130-214; ii. 3. 80-110, 132-151; iii. 4 letter: v. 3 concluding part – which are of very early date; certainly written not later than 1593. It is not, however, in my opinion, to be identified with Love's Labour's Won: the allusions to the present title in iv. 4. 35; v. 1. 24; v. 3. 333, 336, all occur in rhyme passages, and some of them, at least, belong to the earlier date. The play, as we have it, was written after Marston's Jack Drum's Entertainment (1600), to which there is a palpable allusion in iii. 6. 41; and before The Dutch Courtesan (probably 1602) by the same author, which contains several allusions to its title. The name Corambus in iv. 3. 185 suggests the same date, as this is the appellation of Polonius in the Quarto Hamlet. The introduction of Violenta, a mute character, in iii. 5, and the substitution of the same name in Twelfth Night, i. 5, for Viola, show that this last-named play was the last written of the two, but not much interval could have occurred between them. In confirmation of this approximation of dates, compare the name Capilet, v. 3. 147, 159, with Twelfth Night, iii. 4. 315. In plot this play agrees with Much Ado in the supposed death of Helen, and the promise of Bertram to marry Maudlin Lafeu; with Measure for Measure, in the substitution of Helen for Diana; with The Gentlemen of Verona, in Helen's pilgrim disguise, and her meeting with the Hostess. In it and Twelfth Night we find a few slight allusions to the Puritans; another confirmation of date. The only other use even of the word Puritan is in the late play Winter's Tale, iv. 3. 46. Compare the doubtful Pericles, iv. 6. 9. The way in which the earthquake is mentioned in i. 3. 91, gives a still further confirmation. There was an earthquake in London in 1601. I take the boasting Parolles to be Marston; born under Mars, muddied in Fortune's displeasure, an egregious coward, an accuser of Captain Dumain of being lousy, he in all points agrees with Marston, as figured in the other satirical plays of the time. The charge against Dumain is repeated against Jonson in Satiromastix; Marston had left the Admiral's company in 1599, just before the Fortune Theatre was built for them. His cowardice is dilated on in Jonson's Conversations, and the allusions to him as Jack Drum are frequent in the play. Once we find Tom Drum in v. 2 (from Tom Drum's Vants in Gentle Craft, 1598), a hint that Thomas Dekker, author of The Shoemaker's Holiday, or The Gentle Craft (1600), was aiding and abetting John Marston in his satirical plays. Helen was acted by a short boy (i. 1. 202). The incident of the King's gift to Helen of his ring, only referred to in the last scene, seems to point at the gift of a ring to Essex by Elizabeth in 1596. Essex was executed in 1601, just before this play was acted. The older parts pointed out above were, I think, incorporated from detached scenes written in 1593 during the plague time, and laid by for future use. The plot is from Giletta of Narbonne in Painter's Palace of Pleasure, a book used by Shakespeare in 1594 for his alteration of Edward III. Mr. Stokes says that Eccleston and Gough acted in this play, on the authority of Mr. Halliwell; one of the many ignes fatui that have misled this unwary compiler.

1601-2Twelfth Night, or What You Will, was first acted 2d February 1602 at one of the Inns of Court (Manningham's Diary). Its date lies between Marston's Malcontent (1602), (of Malevole in which play Malvolio is clearly a caricature), and What You Will(1602) by the same author. This adoption of the name of his play seems to have induced Shakespeare to replace it by the now universally adopted title. The appellation Rudesby (v. 1. 55) is from Chapman's Sir Giles Goosecap(1601). Several minor points have been already noticed under the previous play All's Well. In this play, as in that, I believe that earlier written scenes have been incorporated. It is only in similar cases that we find such contradictions as that between the three months' sojourn of Viola at the Count's court (v. 1), and the three days' acquaintance with the Duke in i. 4. In ii. 4 there are palpable signs of alteration, and iii. 1. 159-176, v. 1. 133-148 are surely of early date. Moreover, the singular agreement of the plot with the Comedy of Errors in the likeness of the twins, and with The Gentleman of Verona, or rather with Apollonius and Sylla, whence part of that play was derived, point to a likelihood that the first conceptions of these plays were not far apart in time. I think the early portions were written in 1593, like those of the preceding play. For the change from Duke (i. 1-4) to Count in the rest of the play compare The Gentlemen of Verona. I believe that Sir Toby represents Jonson and Malvolio Marston; but that subject requires to be treated in a separate work from its complexity.

1602Troylus and Cressida was published surreptitiously in 1609, with an address to the reader stating that it had been "never staled with the stage." This statement was withdrawn in the same year, and a new title-page issued, "as it was acted by the King's Majesty's servants at the Globe." It had in fact been entered in S. R. 1603, February 7, by J. Roberts, and licensed for printing, "when he hath gotten sufficient authority for it" – which he evidently did not get. It could not therefore have been produced later than 1602. Nor could it, as we have it, have been earlier; the line i. 3. 73, "rank Thersites with his mastic jaws" evidently alluding to Dekker's Satiro-Mastix (1601). I once thought Marston, as Histriomastix or Theriomastix, was alluded to; but the character of Thersites suits Dekker, not Marston. Jonson describes him in The Poetaster, iii. 1, as "one of the most overflowing rank wits in Rome; he will slander any man that breathes if he disgust him." In 1602, Jonson, Marston, and Shakespeare had become reconciled; of reconciliation with Dekker, at any time, there is no trace. This play is probably the "purge" given by Shakespeare to Jonson when he put down all those "of the university pen" (The Return from Parnassus, iv. 3, acted in the winter 1602-3); Ajax representing Jonson, Achilles Chapman, and Hector Shakespeare: but whether this conjecture be true or no, Dekker is certainly Thersites. All this part of the play (the camp story) splits off from the love story of Troylus and Cressida, which is of much earlier date, c. 1593. The two parts are discrepant in minor points, notably in the existence of a truce (i. 3. 262), "dull and long-continued" fighting having been abundant in i. 2. The parts written in 1602 are i. 3; ii. 1; ii. 2; ii. 3; iii. 3. 34 to end; iv. 5. (except lines 12-53); v. i; v. 2 (retains much older work); v. 3. 1-97. All this part bears evident marks of the reading of Chapman's Iliad i. – vii. (1598); the love story is somewhat from the old Troy book printed by Caxton, but more from Chaucer's Troilus and Cressid. At the end of v. 3, in the Folio v. 10. 32-34, are repeated; this shows that the 1602 acting copy was meant to end with v. 3, thus making the play a comedy; as it now stands it is usually classed with the tragedies; in the Folio, it is placed unpaged between the Histories and Tragedies, and is not mentioned in the "Catologue" of contents. The prologue and v. 4-10 contain much work that is unlike Shakespeare's, and are probably by some coadjutor whose other lines have been replaced by the 1602 additions. Heywood in his Iron Age treated this same subject, and the date of that play is important in this investigation. The Ages of Heywood were acted before 1611 (see his Address to the Reader in The Golden Age); The Iron Age was "publicly acted by two companies on one stage at once," and "at sundry times thronged three several theatres." These were the Rose, the Curtain, and the Bull; Pembroke's men, and the Admiral's, acted together at the Rose, October to November 1597. This must have been the time when the Iron Age was performed; but not as a new play. It would otherwise have been entered in Henslowe's Diary as such. All the Ages were then probably old in 1597. In 1595-6 we find them accordingly entered by Henslowe under other names; in 1595, March 5, The Golden Age, whose scenes are in Heaven and Olympus, appears as Steleo (Cœlo) and Olempo; he subsequently writes Seleo for Steleo; The Silver and Brazen Ages on May 7 and May 23, as the first and second parts of Hercules. These three plays were produced in succession. The entry of Galfrido and Bernardo is a forgery, and a clumsy one, for it necessitates a Sunday performance, which is a thing unknown in Henslowe's Diary, if the dates be properly corrected. On 23d June 1596, Troy was acted, palpably The Iron Age; and on 7th April 1597, Five Plays in One may have been the second part of that play. About February 1599, Heywood left the Admiral's men, and joined Lord Derby's; in April, Dekker and Chettle produced their Troylus and Cressida; in May their Agamemnon, and Dekker his Orestes' Furies. I believe that all these were merely enlargements of Heywood's Iron Age. Dekker was a "dresser of plays" and a shameless plagiarist; witness the stealing of Day's work, which he afterwards reclaimed in his Parliament of Bees. At the same time that Dekker was thus pillaging Heywood, his friend Marston was satirising Heywood as Post-haste in Histriomastix for appropriating Shakespeare's Troylus (of 1593) and bringing out The Prodigal Child, the old Acolastus of 1540, as a new play. There can be no doubt that the company satirised in Histriomastix is Derby's. It was a "travelling" company, newly set up, with a poet who extemporises his plays (Heywood had a share in 220) and uses

"No new luxury of blandishment,But plenty of Old England's mother's words."The allusion to Troylus, l. 267-275, in which "he shakes his furious spear," has led some persons to a very absurd identification of Posthaste with Shakespeare. I have noticed before the singular allusion to The Iron Age in John iv. 1. 60 (1596).

1603The Taming of the Shrew is unlike any play hitherto considered; the Shakespearian part of it being evidently confined to the Katharine and Petruchio scenes – ii. 1. 167-326; iii. 2 (except 130-150, 242-254); iv. 1; iv. 3; iv. 5 (except three lines at end); v. 2 (except ten lines at conclusion). The construction of the play shows that it was not composed by Shakespeare in conjunction with another author, but that his additions are replacements of the original author's work; alterations made hurriedly for some occasion when it was not thought worth while to write an entirely new play. Such an occasion was the plague year of 1603, when the theatres were closed and the companies had to travel. We shall see, hereafter, that Shakespeare's other similar alterations of other men's work were made in like circumstances. This date is confirmed by the allusions to other taming plays, of which there were several; the present play, in its altered shape, being probably the latest: ii. 1. 297 refers to Patient Grissel, by Dekker, Chettle, and Haughton, December 1599; "curst" in ii. 1. 187, 294, 307; v. 2. 188, to Dekker's Medicine for a Curst Wife, July 1602; and iv. 1. 221 to Heywood's Woman Killed with Kindness, March 1603. There is nothing but the supposed inferiority of work to imply an earlier date; and this, on examination, will be seen to be merely a subjective inference arising from the reflex action of the less worthy portion with which Shakespeare's is associated. Rudesby in iii. 2. 10 is from Sir Giles Goosecap (1601), and Baptista, as a man's name, could hardly have come under Shakespeare's notice, when in his Hamlet he made it a woman's. The earlier play thus altered probably dates 1596, when an edition of The Taming of a Shrew was reprinted. This last-named play was written for Pembroke's company in 1588-9. Another limit of date is given by the name Sincklo in the Induction. Sinklo was an actor with the Chamberlain's men, from 1597 to 1604. Nicke in iv. 1. is Nicholas Tooley. The play is not mentioned by Meres in 1598. In the Induction, "The Slys are no rogues: we came in with Richard Conqueror," is, I think, an allusion to the stage history of the time. Sly and Richard the Third (Burbadge) came into Lord Strange's company together in 1591. In the Pembroke play, Don Christophero Sly was probably acted by Christopher Beeston. The Induction, partly revised by Shakespeare, seems to have been clumsily fitted by the players (as, indeed, the whole play is, especially in the non-appearance of "my cousin Ferdinand," iv. 1. 154, whose place seems to be taken by Hortensio): surely Sly ought to have been replaced, as in the 1588 play; and is it possible that Shakespeare even in a farce should have made Sly talk blank verse, sc. 2, l. 60-120? The Taming of a Shrew, as acted in June 1594 at Newington Butts, was the old play which had belonged to Pembroke's men, probably by Kyd; but the first version of the play, afterwards altered by Shakespeare, was written, I think, by Lodge, (? aided by Drayton in the Induction). This Induction was, I think, greatly altered by Shakespeare in 1603.