полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

A Chronicle History of the Life and Work of William Shakespeare

• 20. Fortunatus. T. [Printed in German, 1620, as Comedy of Fortunatus and his Purse and Wishing Cap, in which appear first three dead souls as spirits, and afterwards the Virtues and Shame. Evidently from the first part of Fortunatus by Dekker, as acted, 3d February 1596, as an old play. It was probably written c. 1591. This play like (16.) ought to be made accessible to English readers.]

• 21. Joseph, the Jew of Venice. C. [From another early play of Dekker's, c. 1591. The German version is extant in MS. in the Imperial Library at Vienna, and ought to be edited and translated. The Jew, however, is therein called Barabbas, and there are three suitors, as in Shakespeare's play, but no caskets. Dekker's play was entered 9th September 1653 on S. R.]

• 22. The Dextrous Thief. T.C.

• 23. Duke of Venice. T.C.

• 24. Barrabas, the Jew of Malta. T. [Marlowe's play, 1589.]

• 25. Old Proculus. C.

• 26. Lear, King of England. T. [From the old Queen's play, c. 1589. Yet it is strange that it should be called a tragedy. It would hardly be Shakespeare's play, as no other of so late date occurs in the list.]

• 27. The Godfather. T.C.

• 28. The Prodigal Son. C. [Printed in German, 1620. Translated in Simpson's School of Shakespeare. Probably from an old play revived by Heywood for Derby's men c. 1599, but originally founded on Greene's Mourning Garment, 1590, and written (for what company?) c. 1591. So I conjecture.]

• 29. The Graf of Angiers. C.

• 30. The Rich Man. T. [Acted on 17th September 1646 as The Rich Man and the Poor Lazarus. Perhaps from a very old play by Ralph Radcliffe before 1553; more likely from the Moral by the player (? R. Wilson) in Greene's Groatsworth of Wit, 1592, who wrote the Moral of Man's Wit and the dialogue of Dives, and played in Delphrigus, The King of Fairies, The Twelve Labors of Hercules, and The Highway to Heaven.]

It appears from this list that while only one, if any, of these plays, Dorothea, which was probably taken with them by the Revels' company in 1625, can be assigned to a comparatively late date with certainty, the majority are early productions, anterior to 1592. Bearing in mind that there were a large number of plays published before 1626 which might have been used without fear of any opposition from companies in England, it is clear that in Germany the preference was given to older plays, which must have been imported at an early date, either by Leicester's players in 1586, by Pembroke's in 1599, or Worcester's [Admiral's] in 1590 and 1592. Leicester's returned to England in 1577 and Pembroke's c. 1601; but Worcester's, or rather a detachment from the Admiral's, were permanently established in Germany. E. Brown and R. Jones indeed came back to England; but Thomas Sackville and John Broadstreet are traceable in Germany, the latter to 1606 and the former to 1617. There is little doubt that the Hamlet and Romeo, in their German versions, are from early plays, anterior to 1592. This conclusion is confirmed by the list of plays published in Germany in 1620, "acted by the English in Germany at Royal, Electoral, and Princely Courts: " —

• 1. Queen Esther and Haughty Haman. C. [16. in previous list.]

• 2. The Prodigal Son, "in which Despair and Hope are cleverly introduced." C. [28. in previous list.]

• 3. Fortunatus and his Purse and Wishing Cap, "in which appear first three dead souls as spirits, and afterwards the Virtues and Shame." C. [20. in previous list.]

• 4. A King's Son from England and a King's Daughter from Scotland. C. [Serule and Astræa; probably the same as Serule and Hypolita, acted 1631.]

• 5. Sidonia and Theagine. C.

• 6. Somebody and Nobody. C. [10. in previous list.]

• 7. Julio and Hypolita. T. [Query, Philippo and Hypolita, acted as an old play at the Rose, 9th July 1594; similar in plot to The Gentlemen of Verona.]

• 8. Titus Andronicus. T. [Not our extant play, but the Titus and Vespasian acted by Lord Strange's men, April 1592.]

• 9. The Beautiful Mary and the Old Cuckold. A merry jest.

• 10. In which the clown makes merry pastime with a stone.

I am not acquainted with Ayres's plays; but it appears from Cohn (p. 64) that among them are Mahomet the Turkish Emperor (from Peele's play, c. 1591), The Greek Emperor at Constantinople and his daughter Pelimperia with the hanged Horatio (Kyd's Spanish Tragedy, 1588); Valentine and Orson (from an old English play S. R. 23d May 1595); Edward III., King of England, and Elisa Countess of Warwick (from Marlowe's play, 1590: Philip Waimer had already dramatised the same subject at Danzig in 1591); The Beautiful Phenicia (on the same story as Much Ado, and strongly confirming the identity of that play with Love's Labour's Won, 1590: Cupid enters in person, and shoots Count Tymborus, the Benedick of the German version); The Two Brothers of Syracuse (from the Comedy of Errors, c. 1590); The Beautiful Sidea (containing some incidents showing that it came from some source in common with that of the Tempest, but certainly not from that play direct); and King of Cyprus (founded on the same story as The Dumb Knight by Machin and Markham, c. 1607). Cohn does not give exact dates of authorship, but is of opinion that we should not assign to any a year later than 1600; and in 1605 Ayres died. Here again we meet with the same phenomenon – acquaintance with many English plays of date anterior to 1592; but not with any one that can be shown to be later. No doubt Ayres's knowledge of English plays was obtained from the Worcester's (Admiral's) company, who went over in 1590-2.

Yet further, in the tragedy of An Adulteress by Duke Henry Julius of Brunswick, printed 1594, we find the plot of The Merry Wives almost identically reproduced (see Cohn, p. 45, &c.) I do not see, however, so much likeness between his Vincentius Ladislaus and Much Ado.

As regards Shakespearian chronology, it results from this examination of English plays in Germany that there is no positive evidence of English plays of later date than 1592 having been acted there before 1625; that there is evidence that many (a score at least) of date not later than 1592 were acted between 1592 and 1626; that these plays were probably among those imported by Worcester's (Admiral's) players in 1592; and that in the list are contained The Comedy of Errors, Romeo and Juliet, The Merry Wives, The Gentlemen of Verona, and Love's Labours Won, i. e. every play by Shakespeare except Love's Labour's Lost, that is in this treatise placed at a date not later than 1592; besides Kyd's Hamlet, Marlowe's Edward III., and other plays with which Shakespeare was indirectly connected.

APPENDIX

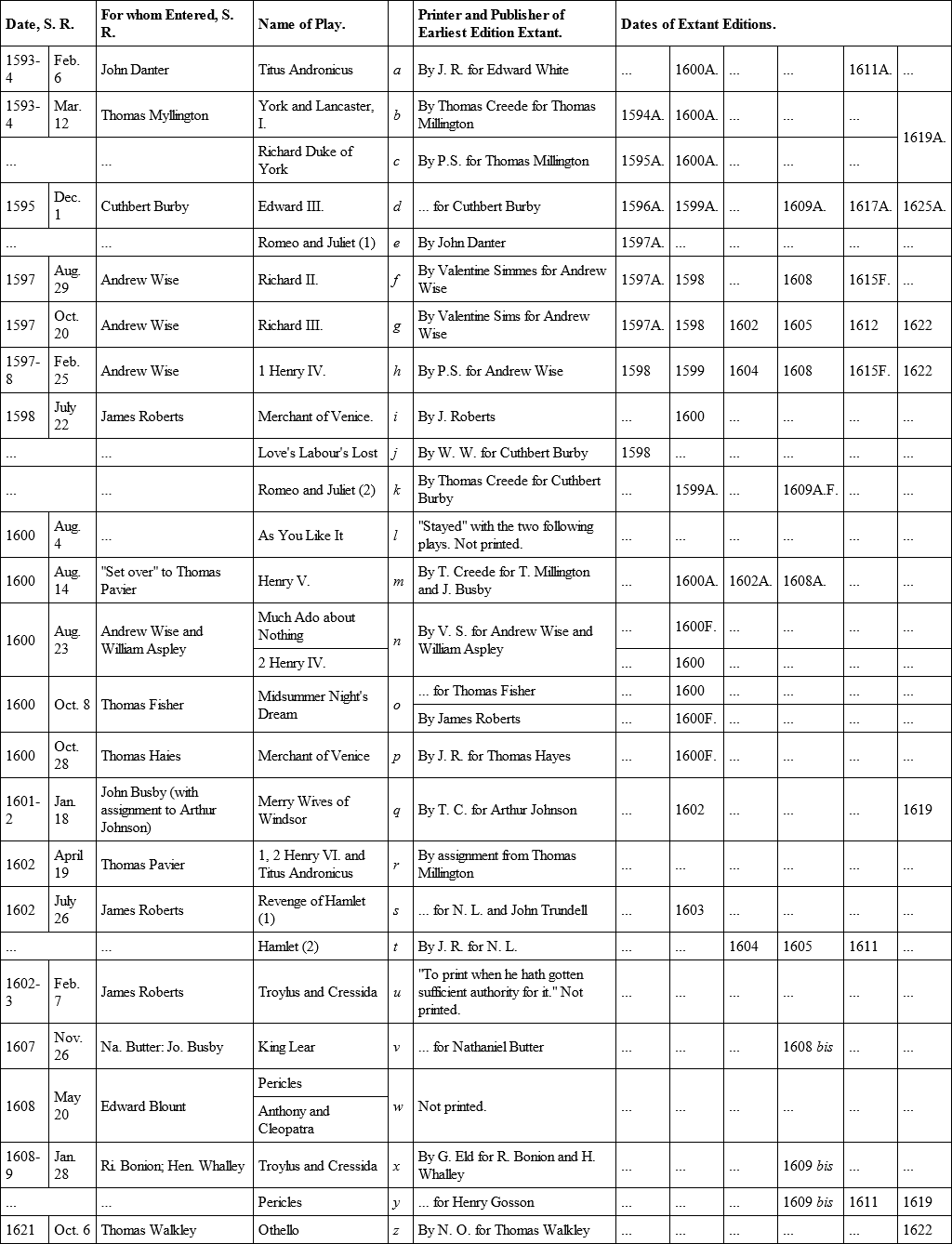

In Table I. I give the dates of the Stationers' Registers entries of Shakespeare's plays as collected in 1623, the printers and publishers of the earliest extant edition of each, and the dates of all known subsequent editions anterior to the 1623 Folio. A. appended to a date means Anonymous, i. e. published without the author's name; F. means that the edition was used by the Folio editors as copy to print from. The relative popularity of the plays will be in some measure seen by a glance at this table. The most popular were Richard III. (six editions in sixteen years); I Henry IV. (six editions); Edward III. (five editions in twenty years); Richard II. (four editions in nineteen years); Henry V. (three editions in nine years). All these were Histories. Next to the Histories rank the Tragedies Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and Pericles: the other great tragedies, Lear, Othello, and the Comedies being decidedly less to the popular taste than the Histories. The entries of change of copyright will be found in their places in Table V.

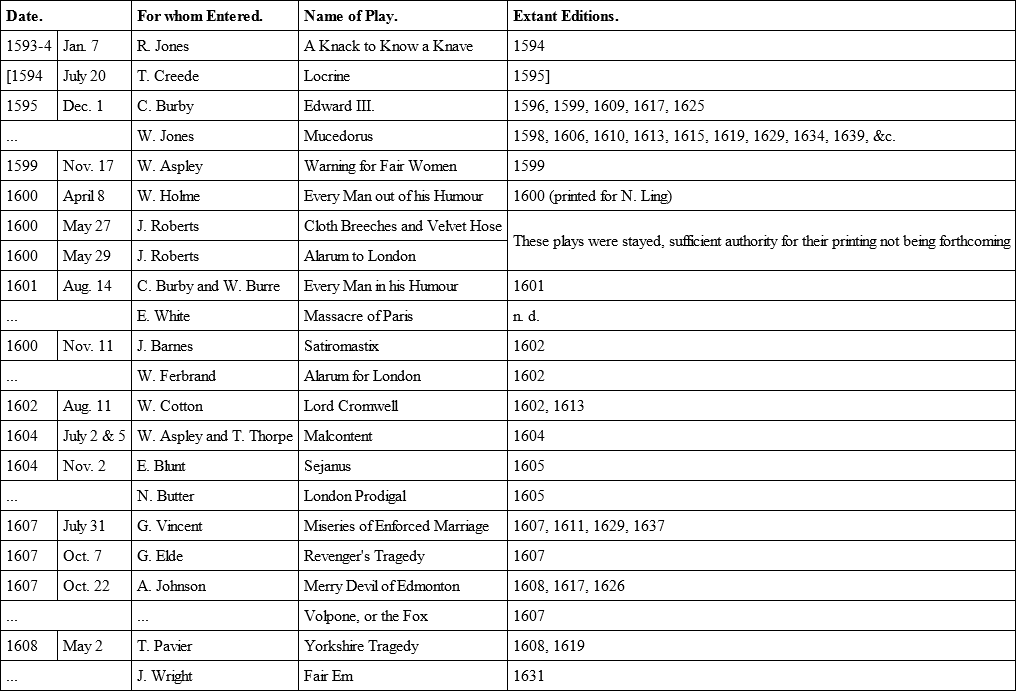

Table II. gives similar information for every known extant play not of Shakespeare's authorship in which he may have been an actor or reviser. Edward III. appears in both these tables. The extreme popularity of Mucedorus is very noticeable.

Table III. gives the number of Court performances in each year for such companies as are known to have been playing in London. From this table it is evident that up to 1591 the Queen's men were the most important of all; in other words, that Greene was the chief Court stage poet, and held the position formerly occupied by Lyly, who wrote for the Chapel children before the public theatrical companies had obtained the prominent place. His chief rival was Marlowe of the Admiral's company. But after 1591 Lord Strange's company takes the lead and keeps it, which means that Shakespeare was the principal Court stage writer till 1611. This throws new light on the relations of Greene, Shakespeare, and their respective companies. But this table comprises, in fact, a compendium of the whole stage history of the time; and as the current versions of this history by Collier, Halliwell, and others are replete with blunders, it may be well to give a very short summary of the results of my investigations – proofs, where lengthy, of some minor details being necessarily reserved for a future publication. Column i. concerns one company only: as Lord Leicester's it was acting in London in 1585; in 1586 it was acting on the Continent; in 1587-8 it was travelling about England; after Leicester's death it began in 1589 to act in London, and was patronised by Lord Strange, who became Earl of Derby in 1593: after his death in 1594, Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon, the Lord Chamberlain, became its patron, who died in 1596; they then passed to his heir, George Carey: in 1603 they were patented as the King's men, and retained that title till the closing of the theatres.

Column ii. The Admiral's men were abroad from 1591 to 1594; in 1603 they were assigned to Prince Henry, and after his death in 1612 to the Palsgrave. The Earl of Hertford's men, who appear once in this column, were not a regular London company, but probably invited to play this once at Court while the Admiral's were abroad, in consequence of the Queen having been entertained by Hertford in the preceding year's progress.

Column iii. Queen Elizabeth's company, formed 1583, took the lead till 1591: they only reappear in conjunction with Sussex in 1593-4, when both companies vanish from the London stage. About 1599 Derby's company appears in London: it became Worcester's in 1602, and was assigned to Queen Anne in 1603.

Column iv. The Earl of Oxford's "boys" were in London in 1586; they travelled in the plague year, and are almost certainly the same company who reappear in London in 1589 as Pembroke's. By Marlowe's aid they prospered a year or two, but after his death became insignificant, and are only dimly traceable to 1600.

In 1597 the Chapel children are stated to have occupied Blackfriars, but till 1600 no play is traceable to them. In 1603-4 they were reorganised as the Children of the Revels, and again in 1610 as a new company under the same name: in 1612 they were again reorganised as the second Lady Elizabeth's company, the first of that name, set up in 1611, having broken up.

Column v. The Paul's boys were inhibited c. 1590, re-established 1600, finally put down 1607.

The Duke of York's men were established 1610, and at Prince Henry's death in 1612 took the name of the Prince of Wales' men.

The reader will observe that never more than five companies existed contemporaneously; and scarcely ever more than two of considerable importance. The statements of Collier and Halliwell are grossly exaggerated.

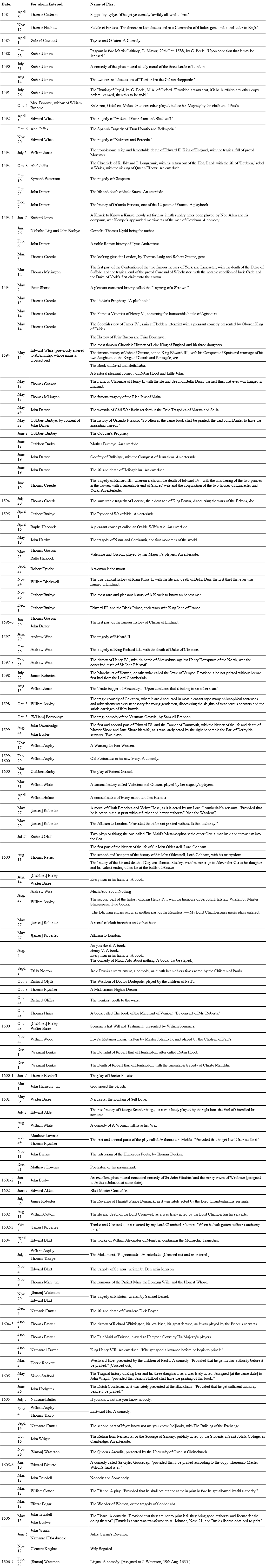

In Table IV. every entry of a play that I can find in the Stationers' Registers is extracted with all necessary fulness. The only point requiring explanation is that the capital letters after the publishers' names indicate the names of the licensers: – T.=Tylney; B.=Sir G. Buck; S.=Segar, his deputy; A.=Sir John Astley; H.=Sir Henry Herbert; T.=Thomas Herbert, his deputy; Bl.=Blagrave, also his deputy. Where the Master of the Revels or his deputy was not the licenser, the insertion of the Wardens' names, &c., would have needlessly encumbered the tables. The spelling has been modernised, except in proper names, &c., where it is of advantage to retain the old forms. These tables afford for the first time complete means of estimating Shakespeare's influence, in I. on the reading public positively; in II. as compared with his co-workers; in III. at Court; in IV. as compared with writers for other companies.

Table V., of transfers of copyright, is, I fear, in spite of much labour, incomplete. Notifications of omission will be welcome and duly acknowledged with gratitude.

TABLES

Table I. – QUARTO EDITIONS OF SHAKESPEARE'S PLAYS.

Table II. – QUARTO EDITIONS OF OTHER PLAYS PERFORMED BY SHAKESPEARE'S COMPANY.

Table III. – NUMBER OF PERFORMANCES AT COURT, 1584-1616.

Table IV. – ENTRIES OF PLAYS IN THE STATIONERS' REGISTERS, 1584-1640.

Table V. – TRANSFERS OF COPYRIGHT IN PLAYS, 1584-1640.

At this point we lose the aid of Mr. Arber's reprint of "The Stationers' Registers," which does not extend beyond 1640. It is, however, necessary to continue our notes to 1660, the date of the reopening of the theatres, because even at that date entries were made attributing plays to Shakespeare. The following memoranda have no pretence to completeness, and are compiled (pending an opportunity of examining the registers themselves) from the much-abused Biographia Dramatica, which is, nevertheless, much more useful than the abbreviated compilation made from it (retaining nearly all its errors) by the scissors of Mr. Halliwell, and published by him as A Dictionary of Old English Plays. Two of these entries are so important for dramatic history that they are printed in parallel columns, with the list of MSS. once in the possession of John Warburton, the Somerset Herald, but mostly destroyed by his cook. From these it will be seen at a glance that three-fifths of his collection consisted of the remainder of Moseley's stock, which contained the majority of old unprinted MSS. extant in 1660.

From these S. R. entries, taken as a whole, the reader will find that the total number of extant plays originally produced between 1576, when theatres were first opened, and their closing in 1642, is less than 500. Nor have we reason to believe that they ever numbered more than 2000 or so. Nearly all worth preserving has been preserved. The gross exaggerations of Halliwell and Collier on this matter depend on their estimating the number of contemporaneous theatres and companies at some fifteen. They really never exceeded five. They also neglect the facts that many so-called new plays were mere revisions of the old ones, "new vamped" versions slightly altered; and that the inferior theatres depended largely on extemporaneous performances, of which only the plots were committed to writing. In the palmy days of the Admiral's company, Henslow brought out a new play once a fortnight, but this was undoubtedly an exceptional instance. The best companies, such as the King's, and after them the Queen's, produced one in about two months. Taking all this into consideration, 2000 is a liberal estimate; 20,000 is a number that could only be dreamed of by an inaccurate writer intent on effect rather than truth. And of this 2000 not more than a quarter would be worth preserving: indeed, of those preserved many are quite valueless. The few good ones lost are such as The Jeweller of Amsterdam, suppressed for political reasons; or the original Henry VIII., destroyed by fire or other accident.

In these Supplementary Lists names of authors wrongly attributed are printed in italics, and names of plays occurring both in Warburton's list and Moseley's entries are asterised.

1646. Sept. 4, were entered, The Spartan Ladies, by Ludovic Carlell; The Corporal and the Switzer, by Arthur Wilson; The Fatal Friendship, by Burroughes.

1653. Sept. 23, The Bondwoman.

1653. Nov. 29 (by R. Marriot), The Black Wedding; Castara, or Cruelty without Lust; The Conceits; The Divorce; The Florentine Friend; A Fool and her Maindenhead soon parted; The Law Case; The Noble Ravishers; The Paraside, or Revenge for Honor, by Henry Glapthorne; Pity the Maids; The Proxy, or Love's Aftergame; The Royal Choice, by Sir Robert Stapylton; Salisbury Plain; Supposed Inconstancy; The Woman's Law; Woman's Masterpiece; The Younger Brother.

1654. April 8, The Apprentice's Prize, by Brome and Heywood; The Life and Death of Sir Martin Skink, with the Wars of the Low Countries, by Brome and Heywood; The Jeweller of Amsterdam, or the Hague, by Fletcher, Field, and Massinger; The Maiden's Holiday, by Marlowe and Day (see Warburton's list).

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE OF MOSELEY'S ENTRIES IN 1653 AND 1660, AND WARBURTON'S LIST.

NOTE ON THE ETCHINGS

I have been asked to say a few words on the illustrations to this volume. The Portrait of Alleyn has been kindly permitted to be taken from the oil painting preserved at Dulwich College, and has not, it is believed, been previously engraved as a book illustration. It was thought that the reader would prefer a representation of this great actor, the first managing director under whom Shakespeare performed, to a reproduction of one of the many portraits of the poet himself, which have now become so hackneyed. For like reason, the Font in which Shakespeare was baptized has been obtained from a hitherto unreproduced original: an oil sketch made on the spot in 1853 by the world-known painter, Mr. Henry Wallis, and now in the artist's possession. It is with no little satisfaction that I find my work allowed to be associated with that of a painter so eminent, and with the name of one of the great poets for all ages, Mr. Robert Browning.

1

"These phrases to their owner I resign,

For God's sake, reader, take them not for mine."

2

It had been reopened in June 1614.

3

The reader should especially beware of a most absurd identification of Shakespeare with the Crispinus of Jonson's Poetaster, recently put forth by Mr. J. Feis in his Shakspere and Montaigne. It is a pity that an essay, of which the first four chapters are so valuable, should be disfigured by the palpable chronological and other blunders in the latter portions of the volume.

4

A dor, dorne, or drone is the lazy male bee that makes no honey: hence Doron, the dorne (pronounce dor´un). There was a myth that dors or drones were produced by mules, hence Muli-dor (see Minshew drone). But a drone is also the drone of a bagpipe, or the bagpipe itself, which was called chevrau (see Cotgrave, chevrau) or cheveril: and chevrau is Kyd. It is evident from Greene's tracts that Doron was meant for the writer of The Taming of a Shrew, and Mulidor for the same author – there cannot be a doubt of the identity of the characters. Nash's address identifies The Taming of a Shrew writer with Kyd.

5

These dates are so given by Henslow: they should be June 5 and June 15.

6

Simpson. But rather in 1 Tamburlane v. 2: "Hell and Elysium swarm with ghosts of men," and similarly a few lines before "where shaking ghosts," &c.

7

Henry V. was transferred to T. Pavier on 14th August.

8

Mr. Halliwell (Outlines, p. 128, 2d edition) says they performed four plays at Whitehall, but quotes no authority.

9

This performance was at Southampton's house before Queen Anne.

10

Mr. Halliwell (Outlines, p. 150) gives December 1609 as the date of this change. This is certainly not in accordance with other facts which I shall adduce in the following pages; he gives no authority for his statement.

11

Cuthbert Burbadge in 1635 adds Field by a slip of memory.

12

This name occurs in Apollonius and Sylla, of which more hereafter.

13

Compare with this Masque, that by Beaumont written for the Inner Temple, 1613.

• 1. "Thy banks with pioned and twilled brims" (Tempest).

"Bordered with sedges and water flowers" (Inner Temple Masque).

"Naiades with sedged crowns" (Tempest).

• 2. "Blessing … and increasing" (Tempest).

"Blessing and increase" (Inner Temple Masque).

• 3. The main part played by Iris in both.

• 4. The dance of the Naiads in both. Many of the properties could be utilised in both performances.

14

Pericles and Edward III. are no exceptions to this statement; the copyrights of both belonged to other publishers, and were retained by these after the Folio was issued.