полная версия

полная версияA Chronicle History of the Life and Work of William Shakespeare

This solidification of the dewdrops does not occur in the Shakespeare parallel, ii. 1. 15. Mr. Halliwell's fancy that Spenser's line in Fairy Queen, vi. – "Through hills and dales, through bushes and through briers" must have been imitated by Shakespeare in ii. 1. 2, is very flimsy; hill and dale, bush and brier, are commonplaces of the time. Nor is there any proof that this song could not have been transmitted to Ireland in 1593 or 1594.

1595Richard II. cannot be definitely dated by external evidence, but all competent critics agree that it is the earliest of Shakespeare's historical plays; the question of authorship, &c., of Richard III. being reserved for the present. It is a tragedy like Marlowe's Edward II., not a "life and death" history. The Civil Wars of Daniel, from which Shakespeare seems to have derived a few hints, was entered on S. R. 11th October 1594. The play probably was produced after this date, and before the publication of the Pope's bull in 1596, inciting the Queen's subjects to depose her. In consequence of this bull the abdication scene was omitted in representation, and in the editions during Elizabeth's lifetime. In like manner, Hayward was imprisoned for publishing in 1599 his History of the First Year of Henry IV., which is simply the story of Richard's abdication. The omitted scene was restored in 1608 under James I. as "new additions." Such new additions on title-pages are often restorations of omitted passages. The Folio copy omits a few other speeches, the play having been evidently found too long in representation; but it contains the abdication scene. This being the first play of Shakespeare's that passed the press was carelessly corrected, whence much apparently unShakespearian and halting metre, which is easily set right. The source of the plot is Holinshed's Chronicle; "the earlier play on Richard II. lately printed" (says Mr. Stokes in 1878) "I have not seen; but it concludes with the murder of the Duke of Gloster." The play seen at the Globe by Forman in 1611 began with the rebellion of Wat Tyler. It was not Shakespeare's. There is no prose in this play, in John, or the Comedy of Errors; a sign of early work.

1595The Two Gentlemen of Verona is a striking instance of the difficulties in which we are involved if we attempt to assign a single date for the production of every play, and neglect the fact that alterations were and are continually made by authors in their works. Drake and Chalmers date this play in 1595; Gervinus, Delius, and Stokes 1591. Malone at different times adopted both dates. I believe that all these opinions are reconcilable, that the play was produced in 1591, with work by a second hand in it, which was cut out and replaced by Shakespeare's own in 1595. For a date after 1593 is distinctly indicated in the play as we have it by the allusions to Hero and Leander in i. 1. 21, iii. 1. 119; and to the pestilence in ii. 1. 20; a still closer approximation is shown to the Merchant of Venice, by the mistake of Padua for Milan in ii. 5. 2. If Shakespeare had not, at the time when he finally produced the Two Gentlemen, begun his study for the Venetian story, whence this name? It only occurs there, once in Much Ado, and in the non-Shakespearian parts of The Taming of the Shrew. In like manner the mistake of Verona for Milan in iii. 4. 81, v. 4. 129, indicates that he had been preparing Romeo and Juliet. That our play lies between the Errors and the Dream on one hand and The Merchant on the other, becomes pretty clear by comparing the development of character in the Dromios, Launce and Speed, Lancelot Gobbo; in Lucetta and Nerissa; in Demetrius and Lysander, Valentine and Proteus. Nor are marks of the twofold date wanting. In the first two acts we find Valentine at the Emperor's court, no Duke mentioned; in the last three at the Duke's, no Emperor mentioned. The turning-point is in ii. 4, where, though "Emperor" occurs in the text, "Duke" is used in the stage directions. In i. 1. 32, "If haply won perhaps a hapless gain; if lost, why then a grievous labour won," there is surely an allusion to Love's Labour's Won, and Love's Labour's Lost; we shall see hereafter that in 1591 these were quite recent plays. The Eglamour of Verona mentioned in i. 2. 9 is not the Eglamour of Milan who appears in iv. 3, v. 1. Style and metre require an early date for i. ii. 1-3 and parts of iii. 1; but in any argument of an internal nature, Johnson's weighty remark should be remembered – "From mere inequality, in works of imagination, nothing can with exactness be inferred." The immediate origin of the plot is unknown; parts of the story are identical with those of The Shepherdess Filismena in Montemayor's Diana, translated in MS. by Young, c. 1583, and of Bandello's Apollonius and Sylla in Rich's Farewell to Military Profession (1581). Felix and Philiomena had been dramatised and acted at Court by the Queen's players, 1584-5. That the revision of The Two Gentlemen was hurriedly performed is clear from the unusually large number of Exits and Entrances that are not marked. This hurry accounts, in some degree, for the weakness of the play, which induces so many critics to insist on an early date for it as a whole. Yet the special blemish they discover, v. 4. 83, the yielding up of Silvia by Valentine, is paralleled in the Dream, where (iii. 2. 163) Lysander says, "With all my heart, in Hermia's love I yield you up my part: " and that Shakespeare felt the unreality of this part of the plot is clear from Two Gentlemen, v. 4. 25, which to me seems a manifest reminiscence of his last play, "How like a dream is this I see and hear!" (cf. Midsummer-Night's Dream, iv. 1. 190, "It seems to me that yet we sleep, we dream"). He had been reading Chaucer, as we know, and from him had adopted this method of presenting stories in a dream. A slighter reminiscence of Chaucer's Knight's Tale occurs in the mention of Theseus, iv. 4. 173.

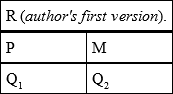

1595-6Romeo and Juliet was surreptitiously printed by J. Danter in 1597; "as it hath been often with great applause played (publicly), by the Rt. Hon. the L. of Hunsdon, his servants." This edition must have been printed in 1596 (old reckoning), for the players would have been called the Chamberlain's servants except during the tenure of that office by W. Brooke, Lord Cobham, from 23d July 1596 to 5th March 1597. That it was on the stage as well as Richard II. in 1595-6, appears from Weever's Epigrams. A correct edition of Romeo appeared in 1599. The relation of these two versions of the play presents a difficult problem. The 1599 Quarto Q2 is unquestionably the play of 1595-6, as acted by the then Chamberlain's players at the Theater; for it does not follow, as Mr. Halliwell supposes, that because they continued to act it when called Lord Hunsdon's players, they had not ever acted it before. Such reasoning would compel us to assign all plays published as "acted by the King's players" to a date subsequent to 1602 —Hamlet, for example, and Troylus and Cressida. Nor does it follow that because it was acted at the Curtain, where Marston mentions it in his Scourge of Villany (S. R. 8th September 1598), that it was produced at that same theatre. Mr. P.A. Daniel has shown, in his Parallel Text Edition, that the 1597 Quarto Q1 is a shortened version of the play, no doubt for stage purposes (compare the Quartos in i. 1; i. 3; iii. 1). He has also with great ingenuity conclusively proved that Q2 is a revised copy made on a text in many places identical with Q1 (see i. 1. 122; i. 4. 62; ii. 3. 1-4; iii. 2. 85; iii. 3. 38-45; iii. 5. 177-181; iv. 1. 95-98, 110; v. 3. 102, 107). But his conclusion that Q1 is partly made up from notes taken during the performance, is not borne out by any evidence. There are no "mistakes of the ear" in this play, nor is this conclusion consistent with his own theory that Q2 was a revision made on the text of Q1. I owe what I believe to be the real solution to a hint from my son, a boy of thirteen. When a play was written and licensed, at least three copies would be made of it. One, with the Master of the Revels' endorsement (which I will call R), would be kept in the archives of the theatre intact; one would be made for the manager (M), which would have occasional notes of stage direction, &c., inserted; and one, an acting copy, for the prompter (P), usually much abridged from the original and always altered: this would contain stage directions, &c., in full, but in the unaltered passages would be identical with M. Now Q1 shows evident signs of being printed from a shortened copy P; Q2 is manifestly a revision of a full copy M. The genealogy of the Quartos then stands thus: —

Q2 is, according to this theory, a revised version made on a complete copy of an early version of the play, while Q1 is printed from the prompter's copy of the same early version. When the revision took place this copy would be thrown aside as worthless; and any dishonest employé of the theatre could sell it to an equally dishonest publisher, who would publish it as the play now acted. If this solution be correct, and it is the only one yet proposed that meets all the difficulties of the case, Q1 is specially interesting as being the earliest extant play (as acted) in which Shakespeare had a share. For it is clear that some passages in it, especially ii. 6, the laments in iv. 5, and Paris' dirge in v. 3, are not only unlike the corresponding passages in Q2, but unlike anything we have from Shakespeare's hand. The date of the early form of the play was 1591, eleven years after the earthquake of 1580 (i. 3. 23, 30). As confirmatory of the conclusion that Q2 was revised from an early play note that in i. 1 the servants are nameless in Q1, but have names in the stage directions in Q2; that in 1. 3 the servant is called clown in Q1; that in iii. 5 in Q2, where the prefixes vary between Lady and Mother, it is in the unaltered parts that Mother is used as in Q1, but Lady always where enough alteration has taken place to require a completely fresh transcript; that in v. 3 there is a double entry marked for the Capulets (a sure sign); that in ii. 3. 1-4, v. 3. 108-111, duplicate versions occur. On the other hand, the printing of the Nurse's speeches in italics in both Quartos is conclusive for identity of origin in that scene. Other points worth noting are that "Queen Mab, what's she?" i. 4. 55 in Q1 are omitted in Q2: Mab had become well known in 1595, probably through Drayton's Nymphidia. In ii. 2. 144, "I am afraid all this is but a dream," reminds us of similar passages in Errors, ii. 2. 184; Two Gentlemen, v. 4. 26; and Dream, iv. 1. 199, &c. W. Kempe acted the part of Peter (see entry in iv. 5); Balthazar is proparoxyton in v. 1. The line in iii. 2, 75, "O serpent heart hid with a flowering face" (where Q1 has "serpent's hate"), is very like the often-quoted "O tiger's heart wrapt in a woman's hide" (3 Henry VI. i. 4. 137). The play is founded on Arthur Brooke's poem, The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet, containing a rare example of true constancy. Constancy in love is its main subject. He took the Italian form of the name Romeo, and the time of Juliet's sleep forty-two hours ("forty at least" in the novel) from Rhomeo and Julietta in Painter's Palace of Pleasure. Much unnecessary writing has been expended on this forty-two hours; the plot requires forty-eight. Daniel, in his Rosamund (S. R. February 1591-2), and the author of Doctor Doddypol (c. October 1594), have passages very like some in this play. A ballad founded on the play was entered S. R. 15th August 1596. On the mention of "the first and second cause" in ii. 4. 26 and (in Q1 only) in iii. 1, some critics base the conclusion that this play must be subsequent to Saviolo's Book of Honour, &c. (S. R. 19th November 1594). I believe that the book referred to is The Book of Honor and Arms, wherein is discussed the CAUSES of quarrel,&c. (S. R. 13th December 1589). The same expression occurs in Love's Labour's Lost, i. 2. 184; in any case it probably belongs to the revised version of this last named play. The alteration in ii. 4 from "to-morrow morning" to "this afternoon," shows that in the revision Shakespeare attended to details in the time of action.

1596King John was founded on the old play acted by the Queen's men, called The Troublesome Reign of King John. The lines ii. 1. 455-460 are imitated in Captain Stukeley by Dekker and others, acted at the Rose, 11th December 1596; iii. 1. 176-179 refer manifestly to the Pope's bull in 1596, inciting the English to depose Elizabeth; Chatillon's speech ii. 1. 71-75 is most applicable to the great fleet sent against Spain in the same year; Constance's lamentations have been reasonably referred to the death of Hamnet Shakespeare (buried 11th August); the Iron Age is alluded to in iv. 1. 60, and never elsewhere in Shakespeare. Now, Heywood's play of that name was on the stage from June 23 to July 16 under the title of Troy. The summer of 1596 is thus undoubtedly the date of Shakespeare's play. There are some indications of the play having been shortened; Act ii. in the Folio has only seventy-four lines, and Essex has a part of only three lines, although in the older John he appears in five scenes. I think he was meant to be entirely cut out c. 1601 after Essex' execution, and these three lines should be given to Salisbury. The rival play of Stukeley was shortened in the same way; a whole act was expunged before its publication in 1605. In i. 2 (Folio) the Citizen on the walls is called Hubert; this indicates that the same actor represented both characters.

1596-7The Merchant of Venice, or Jew of Venice, was no doubt founded on an old play called The Jew of Venice, by Dekker. It seems, from the title of the German version of this play, that the Jew's name was Joseph. The name Fauconbridge in i. 2 (where Portia's suitors are enumerated, compare Two Gentlemen, i. 2) points to a date soon after John; and the "merry devil" of ii. 3. 2, a phrase never elsewhere used in Shakespeare, indicates contemporaneity with The Merry Devil of Edmonton produced in the winter of 1596. Again, the manifest imitations of this play in Wily Beguiled, which I show elsewhere to date in the summer of 1597, give a posterior limit, which must be decisive. This play has no sign whatever of having been altered; the Clarendon Press guesses, founded on the discrepancy of the number of suitors (iv. for vi.) are as worthless as Mr. Hales' proof, referred to by Mr. Halliwell (Outlines, p. 251), of the date of Wily Beguiled. The conclusive evidence of imitation in this play is the conjunction of the "In such a night" lines in scene 16, with the "My money, my daughter" iterations of Gripe in scene 8 of the same play. On 22d July 1598, J. Roberts entered The Merchant or Jew of Venice on S. R., but had to get the Lord Chamberlain's license before printing. On 28th October 1600, he consented to the entry of the play for T. Hayes; nevertheless, he issued copies of his own imprint independently.

1597The First Part of Henry IV. was entered on S. R. 25th February 1598; a genuine and authorised imprint. The publication of this play was hurried in order to refute the charge of attacking the Cobham family in the person of Sir John Oldcastle, the original name of the character afterwards called Falstaff (cf. "my old lad of the castle," i. 2. 48). Moreover, in i. 2. 182, we find in the text the names Harvey and Russel instead of Peto and Bardolph. The name Russel for Bardolph again occurs in a stage direction in 2 Henry IV. ii. 2. These were evidently originally the names of the characters, and were changed at the same time as that of Oldcastle: Russel was the family name of the Bedford Earls, and Harvey that of the third husband of Lord Southampton's mother. The new names were picked up from the second part; in which Lord Bardolph and Peto (a distinct personage from the "humourist" of Part I.) were serious characters. The play was produced in the spring; the only mentions of June in Shakespeare's plays are in ii. 4. 397 (sun F.); iii. 2. 75; and Anthony, iii. 10. 14. In ii. 4. 425, Preston's Cambyses is ridiculed (cf. Dream). There is an imitation of iii. 2. 52 in Lust's Dominion (the Spanish Moor's Tragedy, by Dekker, Haughton, and Day, February 1600, absurdly quoted by Stokes as Marlowe's). For the "abuses of the time" i. 2. 174; iv. 3. 81; see under Sir T. More, 1596. This play, as well as 2 Henry IV. and Henry V., is founded on The Famous Victories of Henry V., an old play produced by the Queen's company; from which the name Oldcastle was taken.

1597-8The Second Part of Henry IV. was entered on S. R. 23d August 1600. This Quarto is much abridged in i. 3, ii. 3, iv. 1, iv. 4, and a whole scene, iii. 1, is omitted. It abounds in oaths apparently foisted in by the players, and is apparently printed from a prompter's copy. The omissions arise, I think, from expurgations made by the Master of the Revels. Plays in which rebellion was the subject were especially disagreeable at Court. In the Epilogue there is evidence of alteration, the words "if my tongue … good-night," having been inserted after the first production of the play, as is clear from their succeeding in Q. the clause about praying for the Queen, which must have been final in either version. The newly inserted words contain the allusion to Oldcastle, and show that in this play, as well as the former, that was the original appellation of Falstaff. This is confirmed by the appearance of Old. in a speech prefix in i. 2. 137; and Russel in a stage direction in ii. 2. Mr. Halliwell's notion that Russel and Harvey were names of actors, has not the slightest foundation, nor are such actors known. Note also that in iii. 2. 29, Falstaff is mentioned as having been page to the Duke of Norfolk, which was historically true of Oldcastle (compare the "serving the good Duke of Norfolk" in The Merry Devil. The date of that play is 1597.) The early part i. 1, or. ii. 4, was written before the entry of 1 Henry IV. on S. R., 25th February 1598, in which Falstaff is mentioned. "Sincklo" occurs in a stage direction in v. 1; he is not known in connection with Shakespeare's company till this play was acted; he was previously a member of Pembroke's troop, and acted in 3 Henry VI. when it belonged to them along with Humfrey [Jeffes], and Gabriel [Singer]. These two last named, and others, joined the Admiral's company at the Rose in October 1597, when Pembroke's men broke and went into the country. Sinkler, Beeston, Duke, and Pallant, stayed with the Chamberlain's men from c. 1594 till they left the Curtain in 1599, and then Kemp, Duke, Beeston, and Pallant set up a new company under the patronage of the Earl of Derby. Not one of these can be shown to have acted for the Chamberlain's, except between these dates, and that they left in discontent is probable from their being all omitted in the list of the 1623 Folio. Sinkler remained in Shakespeare's company till 1604. Pistol, in his first appearance in ii. 4, does not for a while talk in iambics. Mrs. Quickly (i. 2. 269) appears to be called Ursula (Nell in Henry V.) For the changes in the names of this and other characters in the series of Falstaff plays, see hereafter in the table given on p. 207.

1597Love's Labour's Lost was published in 1598, "as it was presented before her Highness this last Christmas." This was undoubtedly the earliest of Shakespeare's plays that has come down to us, and was only retouched somewhat hurriedly for this Court performance. The date of original production cannot well be put later than 1589. The characters are in several instances confused. In ii. 1 Boyet occurs in place of Berowne in the prefixes, and Rosaline for Katharine in the text. In iv. 2, and v. 1, there is still greater muddling of Holofernes and Nathaniel; now one, now the other appears, first as Curate, then as Pedant; in iv. 2, Berowne is called "one of the strange Queen's Lords," and Queen for Princess occurs in the prefixes through the greater part of the play. It is pretty clear that this lady ambassador was in the 1589 play called Queen. In ii. 1, the lines 21-114 were almost certainly added in 1597. They begin with a prefix Prin. inserted in the middle of one of the Queen's (Princess's) speeches; and in them only throughout the play is the prefix Nav. (Navarre) used for King. In iv. 3, the speech of Berowne (l. 290-365) must be mostly assigned to 1597; the repetition of the lines, "From women's eyes … Promethean fire" is an unmistakable indication of revision (see the similar instances in Romeo). A like instance of substitution of a long version for a short one, occurs in v. 1. 847-879, which are manifestly the 1597 substitute for v. 1. 827-832; again, v. 2. 575-590 could not have conveyed any amusement in the conceit of "Ajax" till after the publication of Harrington's Metamorphosis of Ajax in 1596. The mention of "first and second cause," &c., in i. 2. 171-192, may imply that this was another of the additions. But it is in iv. 2 that the greatest changes have been made. It is clear from v. 1. 125, that Sir Holofernes was originally the Curate. Modern editors either omit Holofernes or substitute Nathaniel; Sir Holofernes is also the Curate in iv. 2. 67-156 – "This is a gift … colorable colours." In the rest of this scene Sir Nathaniel is the Curate, and Master Holofernes the Pedant. This latter is the 1597 version. I am not aware that this singular change of character has been noted, or any reason assigned for it, except my conjecture, that it was intended to disguise a personal satire which, however pertinent in 1589, had become obsolete in 1597. For a full discussion of all these changes made in 1597, see my article on Shakespeare and Puritanism in Anglia, vol. 7.

1597-8Much Ado about Nothing is more likely than any other play to be identical with Love's Labour's Won. The internal evidence has been set forth by Mr. Brae; but there are points of external evidence also, that have been overlooked. It is very frequent, in old plays, to find days of the week and month mentioned; and when this is the case, they nearly always correspond to the almanac of the year in which the play was written. Now, in this play alone in Shakespeare is there such a mark of time; comparing i. 1. 285, and ii. 1. 375, we find that the 6th July came on a Monday; this suits the years 1590 and 1601, but none between; an indication that the original play was written in 1590. Unlike Love's Labour's Lost, it was almost recomposed at its reproduction, and this day-of-the-week mention is, I think, a relic of the original plot, and probably due, not to Shakespeare, but to some coadjutor. Again, Meres' list in his Palladis Tamia consists of the following plays: —Gentlemen of Verona (1595), Errors (1594), Love's Labour's Lost (1597), Love's Labour's Won (?), Midsummer-Night's Dream (1594-5), Merchant of Venice (1596-7), Richard II. (1595), Richard III. (1594), Henry IV. (1597), King John (1596), Titus Andronicus (1594), Romeo and Juliet (1595-6). The dates I have appended to these may in some instance be slightly erroneous; but I think no one will deny that the plays mentioned by Meres must have constituted the Shakespeare repertoire of the Chamberlain's men, and have been played by them between the dates of their constitution as a company in 1594, and the publication of Meres' book in 1598. But there is absolutely no other comedy of Shakespeare's that can be assigned to such a date. All's Well that Ends Well was certainly not played by his company so early. Again, Cowley and Kempe played the constables in this play; but Kempe had left the company by the summer of 1599. There is no argument against this conclusion yet produced. The main subject of the play had been dramatised before in Ariodante and Geneuora, acted at Court by the Merchant Tailors' boys in 1582-3. The old German play of Jacob Ayrer, The Beautiful Phœnicia (c. 1595, Cohn) also contains points of similarity with Shakespeare's play that are not found in the Bandello novel which Belleforest translated in 1594. Pedro and Leonato are the only names which Shakespeare retains from the novel; which Ayrer follows in this respect. When the title was altered is doubtful: the play was known as Benedick and Beatrice in 1613.