полная версия

полная версияFragments of Earth Lore: Sketches & Addresses Geological and Geographical

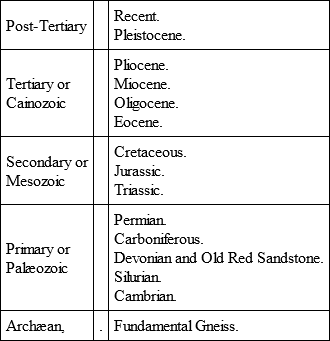

All subsequent geological time – that, namely, of which we have any record preserved in the fossiliferous strata – is divided into four great eras, namely the Palæozoic, the Mesozoic, the Cainozoic, and the Post-Tertiary eras, each of which embraces various periods, as follows: —

Leaving the Archæan, we find that the next oldest strata are those which were accumulated during the Cambrian period, to which succeeded the Silurian, the Devonian and Old Red Sandstone, the Carboniferous, and the Permian periods – all represented by great thicknesses of strata, which overspread wide regions.

Now, at the beginning of the Cambrian period, we have evidence to show that the primeval continental ridge was still largely under water, the dry land being massed chiefly in the north. At that distant date a broad land-surface extended from the Outer Hebrides north-eastwards through Scandinavia, Finland, and northern Russia. How much further north and north-west of the present limits of Europe that ancient land may have extended we cannot tell, but it probably occupied wide regions which are now submerged in the shallow waters of the Arctic Ocean. In the north of Scotland a large inland sea or lake existed in Cambrian times,111 and there is some evidence to suggest that similar lacustrine conditions may have obtained in the Welsh area at the beginning of the period. South of the northern land lay a shallow sea covering all middle and southern Europe. That sea, however, was dotted here and there with a few islands of Archæan rocks, occupying the site of what are now some of the hills of middle Germany, such as the Riesen Gebirge, the Erz Gebirge, the Fichtel Gebirge, etc., and possibly some of the Archæan districts of France and the Iberian peninsula.

The succeeding period was one of eminently marine conditions, the wide distribution of Silurian strata showing that during the accumulation of these, enormous tracts of our Continent were overflowed by the sea. None of these deposits, however, is of truly oceanic origin. They appear for the most part to have been laid down in shallow seas, which here and there may have been moderately deep. During the formation of the Lower Silurian the whole of the British area, with the exception perhaps of some of the Archæan tracts of the north-west, seems to have been under water. The submergence had commenced in Cambrian times, and was continued up to the close of the Lower Silurian period. During this long-continued period of submergence volcanic activity manifested itself at various points – our country being represented at that time by groups of volcanic islands, scattered over the site of what is now Wales, and extending westward into the Irish region, and northwards into the districts of Cumberland and south Ayrshire. Towards the close of the Lower Silurian period considerable earth-movements took place, which had the effect of increasing the amount of dry land, the most continuous mass or masses of which still occupied the northern and north-western part of our Continent. In the beginning of Upper Silurian times a broad sea covered the major portion of middle and probably all southern Europe. Numerous islands, however, would seem to have existed in such regions as Wales, and the various tracts of older Palæozoic and Archæan rocks of middle Germany. Many of these islands, however, were partially and some entirely submerged before the close of Silurian times.

The next great period – that, namely, which witnessed the accumulation of the Devonian and Old Red Sandstone strata – was in some respects strongly contrasted to the preceding period. The Silurian rocks, as I have said, are eminently marine. The Old Red Sandstones, on the other hand, appear to have been accumulated chiefly in great lakes or inland seas, and they betoken therefore the former existence of extensive lands, while the contemporaneous Devonian strata are of marine origin. Towards the close of the Upper Silurian period, then, we know that considerable upheavals ensued in western and north-western Europe, and wide stretches of the Silurian sea-bottom were converted into dry land. The geographical distribution of the Devonian in Europe, and the relation of that system to the Silurian, show that the Devonian sea did not cover so broad an expanse as that of the Upper Silurian. The sea had shallowed, and the area of dry land had increased when the Devonian strata began to accumulate. In trying to realise the conditions that obtained during the formation of the Devonian and the Old Red Sandstone, we may picture to ourselves a time when the Atlantic Ocean extended eastwards over the south of England and the north-east of France, and occupied the major portion of central Europe, sweeping north-east into Russia, and how much further we cannot tell. North of that sea stretched a wide land-surface, in the hollows of which lay great lakes or inland seas, which seem now and again to have had communication with the open ocean. It was in these lakes that the Old Red Sandstone was accumulated, while the Devonian or marine rocks were formed in the wide waters lying to the south. Submarine volcanoes were active at that time in Germany; and similarly in Scotland numerous volcanoes existed, such as those of the Sidlaw Hills and the Cheviots.

The Carboniferous system contains the record of a long and complex series of geographical changes, but the chief points of importance in the present rapid review may be very briefly summed up. In the earlier part of the period marine conditions prevailed. Thus we find evidence to show that the sea extended further north than it did during the preceding Devonian period. During the formation of the mountain-limestone, a deep sea covered the major portion of Ireland and England, but shallowed off as it entered the Scottish area. A few rocky islets were all that represented Ireland and England at that time. Passing eastwards, the Carboniferous sea appears to have covered the low-grounds of middle Europe and enormous tracts in Russia. The deepest part of the sea lay over the Anglo-Hibernian and Franco-Belgian areas; towards the east it became shallower. Probably the same sea swept over all southern Europe, but many islands may have diversified its surface, as in Brittany and central France, in Spain and Portugal, and in the various areas of older Palæozoic and Archæan rocks in central and south-west Europe. In the latter stages of the Carboniferous period, the limits of the sea were much circumscribed, and wide continental conditions supervened. Enormous marshes, jungles, and forests now overspread the newly-formed lands. Another feature of the Carboniferous was the great number of volcanoes – submarine and sub-aërial – which were particularly abundant in Scotland, especially during the earlier stages of the period.

The rocks of the Permian period seem to have been deposited chiefly in closed basins. When, owing to the movement of elevation or upheaval which took place in late Carboniferous times, the carboniferous limestone sea had been drained away from extensive areas in central Europe, wide stretches of sea still covered certain considerable tracts. These, however, as time went on, were cut off from the main ocean and converted into great salt lakes. Such inland seas overspread much of the low-lying tracts of Britain and middle Germany, and they also extended over a broad space in the north-east of Russia. It was in these seas that the Permian strata were accumulated. The period, it may be added, was marked by the appearance of volcanic action in Scotland and Germany.

So far, then, as our present knowledge goes, that part of the European continent which was the earliest to be evolved lay towards the north-west and north. All through the Palæozoic era a land-surface would seem to have endured in that direction – a land-surface from the denudation or wearing down of which the marine sedimentary formations of the bordering regions were derived. But when we reflect on the great thickness and horizontal extent of those sediments, we can hardly doubt that the primeval land must have had a much wider range towards the north and north-west than is the case with modern Europe. The lands, from which the older Palæozoic marine sediments of the British Islands and Scandinavia were obtained, must, for the most part, be now submerged. In later Palæozoic times land began to extend in the Spanish peninsula, northern France, and middle Europe, the denudation of which doubtless furnished materials for the elaboration of the contemporaneous strata of those regions. Southern Europe is so largely composed of Mesozoic and Cainozoic rocks that we can say very little as to the condition of that area in Palæozoic times, but the probabilities are that it continued for the most part under marine conditions. In few words, then, we may conclude that while after Archæan times dry land prevailed in the north and north-west, marine conditions predominated further south. Ever and anon, however, the sea vanished from wide regions in central Europe, and was replaced by terrestrial and lacustrine conditions. Further, as none of the Palæozoic marine strata indicates a deep ocean, but all consist for the most part of accumulations formed at moderate depths, it follows that there must have been a general subsidence of our area to allow of their successive deposition – a subsidence, however, which was frequently interrupted by long pauses, and sometimes by movements in the opposite direction.

The first period of the Mesozoic era, namely, the Triassic, was characterised by much the same kind of conditions as obtained towards the close of Palæozoic times. A large inland sea then covered a considerable portion of England, and seems to have extended north into the south of Scotland, and across the area of the Irish Sea into the north-east of Ireland. Another inland sea extended westward from the Thüringer-Wald across the Vosges into France, and stretched northwards from the confines of Switzerland over what are now the low-grounds of Holland and northern Germany. In this ancient sea the Harz Mountains formed a rocky island. While terrestrial and lacustrine conditions thus obtained in central and northern Europe, an open sea existed in the more southerly regions of the continent. Towards the close of the period submergence ensued in the English and German areas, and the salt lakes became connected with the open sea.

During the Jurassic period the regions now occupied in Britain and Ireland by the older rocks appear to have been chiefly dry land. Scotland and Ireland, for the most part, stood above the sea-level, while nearly all England was under water – the hills of Cumberland and Westmoreland, the Pennine chain, Wales, the heights of Devon and Cornwall, and a ridge of Palæozoic rocks which underlies London, being the chief lands in south Britain. The same sea overflowed an extensive portion of what is now the Continent. The older rocks in the north-west and north-east of France, and the central plateau of the same country, formed dry land; all the rest of that country was submerged. In like manner the sea covered much of eastern Spain. In middle Europe it overflowed nearly all the low-grounds of north Germany, and extended far east into the heart of Russia. It occupied the site of the Jura Mountains, and passed eastward into Bohemia, while on the south side of the Alps it spread over a large part of Italy, extending eastward so as to submerge a broad area in Austria-Hungary and the Turkish provinces. Thus the northern latitudes of Europe continued to be the site of the chief land-masses, what are now the central and southern portions of the Continent being a great archipelago with numerous islands, large and small.

The Jurassic rocks, attaining as they do a thickness of several thousand feet, point to very considerable subsidence. The movement, however, was not continuous, but ever and anon was interrupted by pauses. Taken as a whole, the strata appear to have accumulated in a comparatively shallow sea, which, however, was sufficiently deep in places to allow of the growth, in clear water, of coral-reefs.

Towards the close of the Jurassic period a movement of elevation ensued, which caused the sea to retreat from wide areas, and thus when the Cretaceous period began the British region was chiefly dry land. Middle Europe would seem also to have participated in this upward movement. Eventually, however, subsidence again ensued. Most of what are now the low-grounds of Britain were submerged, the sea stretching eastwards over a vast region in middle Europe, as far as the slopes of the Urals. The deepest part of this sea, however, was in the west, and lay over England and northern France. Further east, in what are now Saxony and Bohemia, the waters were shallow, and gradually became silted up. In the Mediterranean basin a wide open sea existed, covering large sections of eastern Spain and southern France, overflowing the site of the Jura Mountains, drowning most of the Alpine Lands, the Italian peninsula, the eastern borders of the Adriatic, and Greece. In short, there are good grounds for believing that the Cretaceous Mediterranean was not only much broader than the present sea, but that it extended into Asia, overwhelming vast regions there, and communicated with the Indian Ocean.

Summing up what we know of the principal geographical changes that took place during the Mesozoic era, we are impressed with the fact that, all through those changes, a wide land-surface persisted in the north and north-west of the European area, just as was the case in Palæozoic times. The highest grounds were the Urals and the uplands of Scandinavia and Britain. In middle Europe the Pyrenees and the Alps were as yet inconsiderable heights, the loftiest lands being those of the Harz, the Riesen Gebirge, and other regions of Palæozoic and Archæan rocks. The lower parts of England and the great plains of central Europe were sometimes submerged in the waters of a more or less continuous sea; but ever and anon elevation ensued, and the sea was divided, as it were, into a series of great lakes. In the south of Europe a Mediterranean Sea would appear to have endured all through the Mesozoic era – a Mediterranean of considerably greater extent, however, than the present. Thus we see the main features of our Continent were already clearly outlined before the close of the Cretaceous period. The continental area then, as now, consisted of a wide belt of high-ground in the north, extending roughly from south-west to north-east; south of this a vast stretch of low-grounds, sweeping from west to east up to the foot of the Urals, and bounded on the south by an irregular zone of elevated land having approximately the same trend; still further south, the maritime tracts of the Mediterranean basin. During periods of depression the low-grounds of central Europe were invaded by the sea, and the Mediterranean at the same time extended north over many regions which are now dry land. It is in these two low-lying tracts, therefore, and the country immediately adjoining them, that the Mesozoic strata of Europe are chiefly developed.

A general movement of upheaval112 supervened at the close of the Cretaceous period, and the sea which, during that period, overflowed so much of middle Europe had largely disappeared before the beginning of Eocene times. The southern portions of the continent, however, were still mostly under water, while great bays and arms of the sea extended northwards now and again into central Europe. On to the close of the Miocene period, indeed, southern and south-eastern Europe consisted of a series of irregular straggling islands and peninsulas washed by the waters of a genial sea. Towards the close of early Cainozoic times, the Alps, which had hitherto been of small importance, were greatly upheaved, as were also the Pyrenees and the Carpathians. The floor of the Eocene sea in the Alpine region was ridged up for many thousands of feet, its deposits being folded, twisted, inverted, and metamorphosed. Another great elevation of the same area was effected after the Miocene period, the accumulations of that period now forming considerable mountains along the northern flanks of the Alpine chain. Notwithstanding these gigantic elevations in south-central Europe – perhaps in consequence of them – the low-lying tracts of what is now southern Europe continued to be largely submerged, and even the middle regions of the continent were now and again occupied by broad lakes which sometimes communicated with the sea. In Miocene times, for example, an arm of the Mediterranean extended up the Rhone valley, and stretched across the north of Switzerland to the basin of the Danube. After the elevation of the Miocene strata these inland stretches of sea disappeared, but the Mediterranean still overflowed wider areas in southern Europe than it does in our day. Eventually, however, in late Pliocene times, the bed of that sea experienced considerable elevation, newer Pliocene strata occurring in Sicily up to a height of 3000 feet at least. It was probably at or about that period that the Black Sea and the Sea of Asov retreated from the wide low-grounds of southern Russia, and that the inland seas and lakes of Austria-Hungary finally vanished.

The Cainozoic era is distinguished in Europe for its volcanic phenomena. The grandest eruptions were those of Oligocene times. To that date belong the basalts of Antrim, Mull, Skye, the Faröe Islands, and the older series of volcanic rocks in Iceland. These basalts speak to us of prodigious fissure eruptions, when molten rock welled up along the lines of great cracks in the earth’s crust, flooding wide regions, and building up enormous plateaux, of which we now behold the merest fragments. The ancient volcanoes of central France, those of the Eifel country and many other places in Germany, and the volcanic rocks of Hungary, are all of Cainozoic age; while, in the south of Europe, Etna, Vesuvius, and other Italian volcanoes date their origin to the later stages of the same great era.

Thus before the beginning of Pleistocene times all the main features of Europe had come into existence. Since the close of the Pliocene period there have been many great revolutions of climate; several very considerable oscillations of the sea-level have taken place, and the land has been subjected to powerful and long-continued erosion. But the greater contours of the surface which began to appear in Palæozoic times, and which in Mesozoic times were more strongly pronounced, had been fully evolved by the close of the Pliocene period. The most remarkable geographical changes which have taken place since then have been successive elevations and depressions, in consequence of which the area of our Continent has been alternately increased and diminished. At a time well within the human period our own islands have been united to themselves and the Continent, and the dry land has extended north-west and north, so as to include Spitzbergen, the Faröe Islands, and perhaps Iceland. On the other hand, our islands have been within a recent period largely submerged.

The general conclusion, then, to which we are led by a review of the greater geographical changes through which the European continent has passed is simply this – that the substructure upon which all our sedimentary strata repose is of primeval antiquity. Our dry lands are built up of rocks which have been accumulated over the surface of a great wrinkle of the earth’s crust. There have been endless movements of elevation and depression, causing minor deformations, as it were, of that wrinkle, and inducing constant changes in the distribution of land and water; but no part of the continental ridge has ever been depressed to an abysmal depth. The ridge has endured through all geological time. We can see also that the land has been evolved according to a definite plan. Certain marked features begin to appear very early in Palæozoic times, and become more and more pronounced as the ages roll on. All the countless oscillations of level, all the myriad changes in the distribution of land and water, all the earthquake disturbances and volcanic eruptions – in a word, all the complex mutations to which the geological record bears witness – have had for their end the completion of one grand design.

A study of the geological structure of Europe – an examination of the manner in which the highly folded and disturbed strata are developed – throws no small light upon the origin of the larger or dominant features of our Continent. The most highly convoluted rocks are those of Archæan and Palæozoic age, and these are developed chiefly in the north-western and western parts of the Continent. Highly contorted strata likewise appear in all the mountain-chains of central Europe – some of the rocks being of Palæozoic, while others are of Mesozoic and of Cainozoic age. Leaving these mountains for the moment out of account, we find that it is along the western and north-western sea-board where we encounter the widest regions of highly-disturbed rocks. The Highlands of Scandinavia and Britain are composed, for the most part, of highly-flexed and convoluted rocks, which speak to titanic movements of the crust; and similar much-crushed and tilted rock-masses occur in north-west France, in Portugal, and in western Spain. But when we follow the highly-folded Palæozoic strata of Scandinavia into the low-grounds of the great plains, they gradually flatten out, until in Russia they occur in undisturbed horizontal positions. Over thousands of square miles in that country the Palæozoic rocks are just as little altered and disturbed as strata pertaining to Mesozoic and Cainozoic times.

These facts can have but one meaning. Could we smooth out all the puckerings, creases, foldings, and flexures which characterise the Archæan and Palæozoic rocks of western and north-western Europe, it is certain that these strata would stretch for many miles out into the Atlantic. Obviously they have been compressed and crumpled up by some force acting upon them from the west. Now, if it be true that the basin of the Atlantic is of primeval origin, then it is obvious that the sinking down of the crust within that area would exert enormous pressure upon the borders of our continental area. As cooling and contracting of the nucleus continued, subsidence would go on under the oceanic basin, depression taking place either slowly and gradually, during protracted periods, or now and again more or less suddenly. But whether gradually or suddenly effected, the result of the subsidence would be the same upon the borders of our Continent; the strata along the whole western and north-western margins of the European ridge would necessarily be flexed and disturbed. Away to the east, however, the strata, not being subject to the like pressure, would be left in their original horizontal positions.

Now it can be shown that the mountains of Scandinavia and the British Islands are much older than the Alps, the Pyrenees, and many other conspicuous ranges in central and southern Europe. Our mountains and those of Scandinavia are the mere wrecks of their former selves. Originally they may have rivaled – they probably exceeded – the Alps in height and extent. It is most likely, indeed, that the areas of Palæozoic rocks in France, Portugal, and Spain also attained mountainous elevations. But the principal upheaval of the western margins of our Continent was practically completed before the close of the Palæozoic period, and since that time those elevated regions have been subjected to prodigious erosion, the later formations being in large measure composed of their débris. I do not, of course, wish it to be understood that there has been no upheaval affecting the west of Europe since Palæozoic times. The tilted position of many of our Mesozoic strata clearly proves the contrary. But undoubtedly the main disturbances which produced the folding, fracturing, and contortion of the Palæozoic strata of western Europe took place before the close of the Palæozoic period. The mountains of Britain and Scandinavia are amongst the oldest in Europe.

When we come to inquire into the origin of the mountains of central Europe we have little difficulty in detecting the chief factors in their formation. An examination of the Pyrenees, the Alps, and other hill-ranges having the same general trend shows us that they consist of flexed and convoluted rocks. They are, in short, mountains of elevation, ridged up by tangential thrusts. Of this we need not have the slightest doubt. If, for example, we approach the Alps from the low-grounds of France, we observe the strata as we come towards the Jura beginning to undulate – the undulations becoming more and more marked, and passing into sharp folds and plications, until, in the Alps, the beds become twisted, convoluted, and bent back upon themselves in the wildest confusion. Now, speaking in general terms, we may say that similar facts confront us in connection with every true mountain-range in central Europe. Let it be noted, further, that all those ranges have the same trend, which we may take to be approximately east and west, or nearly at right angles to the trend of the Palæozoic high-grounds of western and north-western Europe. Looked at broadly, our continental ridge may be said to be traversed from west to east by two wide depressions or troughs, separated by the intervening belt of higher grounds just referred to. The former of these troughs corresponds to the great central plain, which passes through the south of England, north-east France, the Low Countries, and Denmark, whence it sweeps east through Germany, and expands into the wide low-grounds of Russia. The southern trough or depression embraces the maritime tracts of the Mediterranean and the regions which that sea covers. Such, then, are the dominant features of our Continent, to which all others are of subordinate importance. Now it cannot be doubted that the two great troughs are belts of subsidence in the continental ridge itself. And their existence explains the origin of the mountain-ranges which separate them. We know that the northern trough is of extreme antiquity; it is older, at all events, than the Silurian period. Even at that distant date its southern limits were marked out by ridges of Archæan rocks, which seem to have formed islands in what is now middle Germany, and probably also in Switzerland and central France. The appearance of those Archæan rocks in central Europe was doubtless due to a ridging up of the crust induced by those parallel movements of subsidence which produced the northern and southern troughs. The northern trough was probably always the shallower depression of the two, for we have evidence to show that, again and again in Mesozoic and later times, the seas which overflowed what are now the central plains of Europe were of less considerable depth than that which occupied the Mediterranean trough. As time rolled on, therefore, the northern trough eventually became silted up; but so low even now is the level of that trough that a relatively slight depression would cause the sea to inundate most extensive regions in middle Europe.