Полная версия

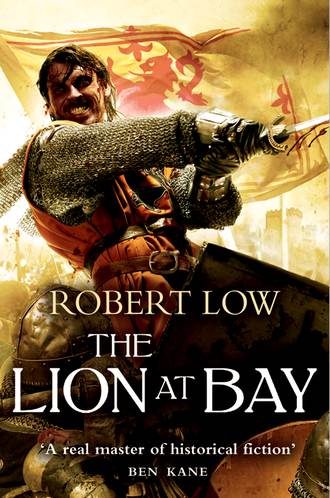

The Complete Kingdom Trilogy: The Lion Wakes, The Lion at Bay, The Lion Rampant

Eventually, Ralph would be made a knight and take no blows he would not return. The thought made him forget himself and smile.

Cressingham looked sourly at the smirking squire holding the gardecorps. The garment was elegant and in the new shade of blue which was so admired by the French king that he had adopted it as his colour. Not diplomatic, Cressingham thought, and made a mental note never to wear it in the presence of Longshanks.

He did not much want to wear it at all and, in truth, hated the garment, for the same reason he was forced to wear it – he was fat and it hid the truth of it. It was, he knew, not his own fault, for he was more of an administrator than a warrior, but you did not get knighted for tallying and accounts, he thought bitterly, for all the king’s admiration and love of folk who knew the business.

As always, there was the moment of savage triumph at what he had become, despite not being one of those mindless thugs with spurs – Treasurer of Scotland, even though it was a Gods-cursed pisshole of a country, was not only a powerful position, but an extremely lucrative one.

As ever, this exultant moment was followed by a leap of utter terror that the king should ever discover just how lucrative; Cressingham closed his eyes at the memory of the huge tower that was Edward Plantagenet, the drooping eyelid that gave him a sinister leer, the soft lisping voice and the great, long arms. He shuddered. Like the grotesque babery carved high up under cathedral eaves and just as unpredictably vicious as those real apes.

He slapped Ralph de Odingesseles for it, for the smirk, for Edward’s drooping eye and this Pit-damned brigand Wallace and for having to wait in this pestilential place for the arrival of De Warenne, the Earl of Surrey.

He slapped the other ear for the actual arrival of De Warenne, the hobbling old goat complaining of the cold and his aches and the fact that he had been trying to retire to his estates, being too old for campaigning now.

Cressingham had no argument with this last and slapped Ralph again because De Warenne had not had the decency to die on his way north with the army, thus leaving Cressingham the best room in Roxburgh, with its fire and clerestory.

Worst of all, of course, was the mess all this would leave – and the cost. Gods, the cost … Edward would balk at the figures, he knew, would want his own inky-fingered clerks poring over the rolls. There was no telling what they might unveil and the thought of what the king would do then almost made Cressingham’s bowels loosen.

Ralph de Odingesseles, trying not to rub his ears, went to the kist in the corner and fetched out a belt with dagger, purse and Keys, the latter the mark of Cressingham’s position as Treasurer, designed to elicit instant respect.

Like most such observances, the truth was veiled, like statues of the Lady on her Feast Days; everyone knew the Scots called Cressingham the ‘Tracherer’ and you did not need to know much of the barbaric tongue to know it meant ‘Treacherer’ and was a play on his title.

Yet he was also the most powerful in Scotland, simply because he held the strings of the purse Ralph now handed him.

He helped fasten on the belt, then adjusted his master’s arms in the sleeves of the long, loose gardecorps; Cressingham consoled himself with the fact that at least his gardecorps was refined. No riotous colours here, no gold dagging along the hem, or long slits up the sides, or three-foot tippets. Plain black, with russet vair round the sleeves and neck, as befitted someone of probity and dignity.

‘I will break fast now,’ Cressingham said and Ralph de Odingesseles nodded, took a step back and bowed.

‘The Seneschal is here. Brother Jacobus also.’

Cressingham frowned and swallowed a curse – couldn’t they at least let him wake up and eat a little? He waved his page away to fetch food and told him to let the Seneschal in, then went to brood at the shuttered window, peering through the cracks rather than open it to the breeze – even in August it was cold. Outside, the river flowed, gleaming as quicksilver and he took comfort from the Teviot on one side and the Tweed on the other, so that the castle seemed to sail on a sea, a boat-shaped confection in stone.

Roxburgh was a massive, thick-walled fortress with four towers and a church within the walls. Cressingham’s room was on a corner of the main Keep overlooking the Inner Bailey and, because of that, had a proper window of leaded glass rather than the shuttered arrow slits that faced the outside. The other sides of his room bordered on a corridor, so there were no windows at all, which made it dim and dark. Not for the first time, Cressingham thought of the light-flooded solar tower and its magnificent floor tiles, where De Warenne had installed himself.

A polite cough turned him and the Seneschal, Frixco de Fiennes, stood, waiting patiently in his sober browns and greens.

‘Christ be praised,’ Frixco de Fiennes said and Cressingham grunted.

‘For ever and ever,’ he responded automatically. ‘What problems have surfaced this early in the day?’

Frixco had been up for several hours and all the lesser folk of the castle hours before that. Half the day was gone as far as Frixco was concerned and he had already dealt with most of the castle’s problems – the cook needing the day’s salt and spices, the Bottler warning that immediate ale stocks were low and small beer lower still.

The other problems he had no answer for were worse -supplies for the 10,000 men currently filtering through Berwick and heading this way, the timber to the workmen scaffolding the Teviot wall in order for minor repairs to be done, men to make spears and quarrels and bows. Where grain for bread was to come from, or fodder for animals, or bedding for horse and hound.

‘The world turns, Treasurer,’ he replied. He should properly have addressed Cressingham as Lord but that was a step too far for the fine-bred Frixco de Fiennes, who was brother to the Warden here. Frixco, however, was not brave, or clever. He should have gone to the Church but liked women too much even to suffer the slight restriction priesthood would place on his whoring – the thought of the splendid Mattie down at the Murdoch’s Tavern in the town tightened his groin so much he almost bent over, convinced it could be seen.

Seneschal here was perfect, for it let him use his skills in tallying and reading and writing in English, French and Latin while leaving him free to plough whatever furrows he could find.

He laid out the problems as Ralph de Odingesseles returned with bread and dishes of mutton, pork and fish. The squire poured watered wine and Frixco stood while Cressingham chewed and swallowed, toying absently with the bread as he walked to the shuttered window and, finally, opened it to the day. Behind him, sly as a mouse, Ralph filched slices of meat and fish, popping it in his mouth at once and ignoring the frowning Frixco.

There was Stirling, one of the main fortresses still held by England. Frixco meticulously listed the castle stores there – 400 barrels of beer, four of honey, 300 of fat, 200 sides of beef, pork and tongue, a single barrel of butter, 10 each of pickled meat and herring, seven of cod, 24 strings of sausages, two barrels of salt and 4,000 cheeses.

‘Enough for six to eight months,’ Frixco de Fiennes ended, ‘given that the garrison is not large. I have assumed that the townsfolk will seek sanctuary within.’

‘If we do not succour the town?’ Cressingham asked and the Seneschal looked astonished at the very idea of not taking in Stirling’s desperate. That was the purpose of the castle, one of the three such purposes fortresses were designed for. One was as a base for the destruction of enemies, the second was the succour of guests and pilgrims and people in their charge and the third was to stamp the authority of the king on the area.

Frixco de Fiennes said nothing, all the same, for he knew that Stirling should have had stores for two years, but complacency and greed had corroded that. In the end, Cressingham gave up expecting a reply.

‘The townspeople of Stirling must work if they wish the protection of the fortress,’ Cressingham declared. ‘Make it clear to them that rations will be given to those who volunteer for service.’

Frixco duly made a note, tongue between his teeth, juggling parchment and quill and the ink pot hung round his neck, though he knew Cressingham only did this because the commander at Stirling was Fitzwarin, a relative of the Earl of Surrey.

Frixco had already delivered lists to Cressingham regarding Roxburgh itself, which should have made it clear to the man how unlikely it was that any castle in Scotland could fully equip enough townspeople – Roxburgh had 100 iron helmets, 17 maille tunics cut for riding, seven pairs of metal gauntlets, two sets of vambrace and a single cuisse. What use a solitary thigh guard? Frixco wondered. And if one was found – what use a one-legged knight?

‘My lord.’

Ralph was back, announcing that the Earl of Surrey and Sir Mamaduke Thweng were in the main hall, awaiting Cressingham’s pleasure. Brother Jacobus had joined them.

The scathe of it lashed Cressingham, so that he scowled. My pleasure, indeed. He was tempted to let them wait – two tottering old warhorses, he thought viciously, though he had to temper that in Sir Marmaduke’s case, since he was younger than De Warenne by a decade or more and still held a formidable reputation as a chivalric knight. Muttering, he swept from his room.

The three sat at the high table benches in the huge hall, misted with faint blue smoke from badly lit fires and empty but for De Warenne, Sir Marmaduke and Brother Jacobus, Cressingham’s chaplain from the Ordo Praedicatorum.

Before Cressingham had even slippered his way across the flagged floor, Frixco scuttling behind him, he could hear De Warenne’s complaints, saw that Thweng stared ahead, forearms on the table, and with the air of a man shouldering through a snowstorm while Brother Jacobus, piously telling his rosary, listened without seeming to listen.

‘Plaguey country,’ the Earl of Surrey was saying, then broke off and looked up at Cressingham with watery, violet-rimmed eyes.

‘Here you are at last, Treasurer,’ he snapped. ‘Did you plan to sleep all day?’

‘I have been busy,’ Cressingham fired back, stung by his tone. ‘Trying to sort out the feeding and equipping of this rabble you have brought, claiming it to be an army.’

‘Rabble, sirra? Rabble …’

De Warenne bristled. His trimmed white beard was shaped into a curve and pointed; with his round arming cap he looked like some old Saracen, Cressingham thought.

‘Good nobiles, chided Brother Jacobus and the soft voice stilled everything. De Warenne muttered, Sir Marmaduke went back to staring at nothing and Cressingham almost smiled, though he resisted the triumph of it, for fear the priest would notice. Domini canes – God’s Dogs – folk called the Order of Preachers, but not to their face, since they had been given the papal permission to preach the Word and root out heresy, a wide and sinister writ.

Now this bland-faced little man sat in his frosting of habit and jet cappa, the over-robe that gave them yet another name, Black Friars. He let the polished rosewood beads slip, sibilant as whispers, through his fingers.

Shaven and washed so clean his face seemed to shine like a white rose, Jacobus was, Cressingham knew, using the rosary as a pointed reminder to everyone that this was the Thursday of the Transfiguration of Christ, one of the days of Luminous Mystery. He also knew those beads were just as easily used to tally and list in the service of the Treasurer; if Jacobus was a hound of God, Cressingham thought, then he is kennelled at my command – though it would be prudent to check his chain now and then.

The beads, click-clicking through the friar’s smooth fingers, brought tallying surging back to Cressingham.

‘Gascons,’ he declared viciously, startling De Warenne out of a slump so suddenly he could not form a response; the air hissed out of the Earl and he gobbled like a chicken.

‘Three hundred crossbows from Gascony,’ Cressingham went on accusingly. ‘Now more than half have no crossbows.’

‘Ah,’ said De Warenne. ‘The carts. Missing. Lost. Strayed.’

‘It was the Earl of Surrey’s quite proper military decision,’ Sir Marmaduke said suddenly, his voice a slice across them both, ‘to relieve the march burden on the Gascons by loading their equipment on wagons. After all, they were not to need it until Berwick, at least – unless your reports were misleading about the extent of the rebel problem and it was possible to have encountered this huge ogre Wallace somewhere around York.’

Cressingham opened and closed his mouth. De Warenne barked a short laugh.

‘Ogre,’ he repeated. ‘I am told he is as large as Longshanks – what say you to that, eh, Cressingham? As big as the king?’

Cressingham did not take his eyes from the long-faced Thweng. Like a mile of bad road in England – or two miles of good in Scotland, he thought.

‘What I say, my lord Earl,’ he said, biting the words off as if they had been dipped in aloes, ‘is that you claim some eight hundred horse and ten thousand foot on the rolls. If they are all as good as your Gascons, we may as well quit this land now.’

‘Equip them with new,’ De Warenne snapped back, waving one hand. ‘Make ‘em if you have none in stores.’

‘We have sixty crossbows only here,’ Frixco murmured.

‘Make ‘em bowmen then – one is as good as the other.’

‘We have some fifteen thousand arrows, my lord,’ Frixco declared humbly, ‘but only one hundred bows.’

‘Then make the damned crossbows,’ bellowed De Warenne. ‘Ye have wood and string, d’ye not? Folk who know the way of it?.

Cressingham’s jowls quivered, but he closed his mouth with a click as Jacobus cleared his throat.

‘If it please you, Lord Earl,’ the friar said, ‘we are short on sturgeon heads, flax threads and elk bones.’

De Warenne blinked. He knew flax was used in the making of the bowstrings, but had no idea why a crossbow needed elk bones or, God’s Wounds, sturgeon heads. All he knew of crossbows was that the lower orders could use them without much training. He roared this out, to the satisfaction of the smirking Cressingham.

‘One is for the sockets,’ Brother Jacobus explained quietly to the Earl. ‘The sturgeon heads supply a certain elasticity not found from any substitute.’

De Warenne waved a scornful, dismissive hand.

‘What do you know, priest? Other than one of your old Councils banned the thing.’

‘Canon 29 of the Second Lateran,’ Cressingham offered haughtily.

‘I understood,’ Sir Marmaduke said, his lips curled in what might have been a wry smile or a sneer. ‘that it was a ban only on foolish marksmanship. Shooting apples from heads and such. A ban on that seems sensible enough.’

Brother Jacobus nodded unctiously.

‘Even if it had been an entire ban,’ he replied, ‘such would not apply to use against unbelievers – Moor and Saracen and the like. Happily, English bishops have declared the Scots rebels excommunicate, which means we may use these anathema weapons freely.’

‘Unhappily,’ Thweng replied dryly, ‘I believe Scotch bishops have excommunicated us, which means the rebels can point them our way, too. The Pope is silent on the matter.’

Jacobus looked at Thweng. It was a look that had seldom failed to make folk quail, combining, as it did, displeasure and pious pity. Sir Marmaduke merely stared back at him, eyes blank and glassed as the black friar’s beads.

Sturgeon bones, De Warenne thought wildly. God’s Wounds, this whole enterprise could fall because we don’t have enough fish heads.

Men and food, the endless problem since armies had started marching. De Warenne felt the crushing weariness of it all – the whole business of this pestilential country was a clear message that Longshanks had displeased God and He had turned His Wrath on them. More to the point, De Warenne thought sourly, Longshanks has displeased the likes of me and, one day soon, I will turn my wrath on him, together with all the other lords fretting under the divine right.

Yet the king was not the throne and De Warenne, Earl of Surrey would defend that to the death. His grandfather had been uncle to the Lionheart himself, his father had been Warden of the Cinque Ports and every De Warenne had been a bulwark against the foes of God, for whoever attacked the throne of England assaulted God Himself. John De Warenne, Earl of Surrey, Warden of Scotland, would hold His Fortress against all the rebel scum of the earth.

The thought drew him up a little, even as a cold wind curled the length of the hall, stirring the smoke into swirls and eddies.

Strike north. Find this Wallace and cut him down shorter than Longshanks, so that the king would be pleased with his earl at that. The thought made De Warenne bark out a laugh.

‘Then there are the Welsh,’ Cressingham declared and De Warenne looked at him with a curled lip. Like a fly, he thought, buzz-buzzing in the ear. One good slap …

‘What of the Welsh?’ Sir Marmaduke asked and watched as Cressingham fussily arranged his blue robe – bad choice of colour for a pasty man, Thweng thought – and imperiously waved at some distant servant. An instant later a man slouched through the far door from the kitchen and across the floor to be eyed up and down. He studied them back from a face dark as an underground dwarf, black-eyed and challenging.

A fist of a face, the beard on it cropped to stubble, but with a great gristle of moustache, as if some giant black caterpillar had crawled under his nose. Cheekbones like knobs and a single scowl of eyebrow – typical Welsh, Sir Marmadule thought, from the south, where the archers are, for the north are mainly spearmen. He said so and De Warenne nodded. Cressingham pouted and scowled.

‘Look at him,’ he said, quivering. ‘Look at what he is wearing.’

Not much, Sir Marmaduke thought – a ragged linen tunic in a distant memory of red, a great shock of dark hair like a sprout of bush on a rock. Nothing on his legs but his bare feet, though there were shoes hung round his neck. He had a leather bracer on one arm, a bow the same size as himself in a bag of some strange-looking leather and a soft bag of the same hanging from one side of a belt, a long, wicked-looking sheathed knife from the other.

In the bag at his hip were arrows, though they were all neatly separated by leather to keep the fletchings from fouling, and the way the bag swung told Sir Marmaduke that it had damp clay shaped to the bottom of it, to prevent the points bursting through.

Across the powerful shoulders, one humped slightly as if he was deformed, hung a long roll and fall of rough wool fabric which had been russet-brown once and was now just dark.

‘A Welsh archer,’ Sir Marmaduke said, ‘with bow, a dozen good arrows and a knife. The thing round his shoulders is a called a brychan if I am not mistaken. Serves as cloak and bed both.’

‘Well, you would know that, certes,’ Cressingham declared with a sneer, ‘since you have spent a deal of your life fighting such. No help in present cirumstances, mark me.’

‘Is there a point to this, Treasurer?’ De Warenne sighed. Cressingham made a show of plucking a paper from Frixco’s fingers.

‘Item,’ he said. ‘Welsh archer, cap-a-pied, with a warbow of yew, one dozen goose-fletched arrows, a sword and a dagger.’

He thrust the paper back at Frixco.

‘This is what is being paid for from the Exchequer,’ he declared triumphantly. ‘And this is what I expect for the price. Cap-a-pied. Which means one hat of iron, one coat of war, either maille or a leather jack, studded for preference. One sword. One yew bow and a dozen finest shafts. That is what is being paid for and that is what we do not have. This man is a ragged-arsed peasant with stick and string, no more.’

Addaf had followed a deal of it, despite their being English, for that tongue was now heard more and more in Wales and it was a sensible man who learned it and spoke it well. Then, he thought, they turn round and speak an even stranger tongue, the French, which wasn’t even their own but belonged to the people they were fighting. Among others.

He had listened quietly, too, for it was also a sensible man who realised that fighting against these folk was now old and done, though the defeat in it was still a raw wound no more than a handful of years gone. Yet taking their money to fight with them was almost as good a revenge for Builth and the loss of Llewellyn and better than starving in the ruin war had made of the valleys.

Yet peasant was too hard for a man of those same valleys to bear.

‘I am Addaf ap Dafydd ap Math y Mab Lloit Irbengam,’ he growled in English, ‘and no peasant with an arse of rags.’

He saw the look on them, the same as the look on folk’s faces when they had seen the two-headed calf at the fair the year he had left. The fat one looked bemused.

‘Do. You. Speak. English?’ this one demanded, leaning forward and talking as if Addaf was a child. The tall one with the long face, the one pointed out as having fought Welsh once, twitched the mourn of his moustaches into a brief smile.

‘You are annoying a Welshman, Treasurer,’ he said, ‘for English is what he is already speaking.’

Addaf saw the fat one bristle like an old boar sow.

‘His name,’ Sir Marmaduke explained, speaking English, both clear and slow, Addaf noted, so that everyone would understand, ‘means Addaf son of David, son of Madog, though the last part confuses me a little – The Brown Lad With The Wrong Head?’

He knew the Welsh – Addaf took to this Sir Marmaduke at once, for he had once been a bold adversary and he knew the Welsh a little and the English as spoken by True People; Addaf heaved a sigh of relief.

‘Dark and stubborn, I am after believing it is in your own tongue,’ he said and added ‘Lord,’ because it did no harm to mark the trail of matters politely.

‘I am from the gwely of Cilybebyll,’ he explained earnestly, so that these folk would know with whom they dealt. ‘I have a cow and enough grazing land to feed eight goats for a year. I am a free man of the True People, by the grace of God, sharing an ox, a goad, a halter and a ploughshare with three others in common. I am not a serf with ragged arse.’

‘Did you understand any of that?’ Cressingham demanded waspishly. Sir Marmaduke turned slowly to him.

‘You have offended him, it appears. In my experience, Cressingham, it does no good to offend a Welshman. Particularly bowmen – see you the shoulder? That hump is pulling muscle, Treasurer. Addaf here has some twenty-odd summers on him and I’ll warrant at least seventeen of them have been used to train with that bow until he can pull the string on one taller than a well-made man and thick as a boy’s wrist, all the way back to his ear. The arrows, I will avow, are an ell at least and are fletched, not with goose, but with peacock, which means they are his finest. This man can put such a shaft through an oak church door at a hundred paces and then another ten or so of its cousins within the minute. If he does his job aright, he will not need iron hat or studded jack or maille – all his enemies will be dead in front of him.’

He broke off and stared fixedly at Cressingham, who did not like the look of him nor of the scowling black-faced Welshman.

‘Christ be praised,’ murmured Brother Jacobus and crossed himself into the twist of Addaf’s smile.

‘For ever and ever,’ they intoned – Addaf louder than the rest, just so the crow of a priest would get the point.

‘I would take our Welshman as is, Treasurer,’ Sir Marmaduke added gently, ‘and be glad of it.’

‘Just so,’ De Warenne added and thumped the table. ‘Now, Treasurer, you can carry on doing what you do best – scribbling and tallying up how to get my army, well fed and in good humour, to where I can meet this Wallace Ogre and defeat him.’