полная версия

полная версияHistory of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2

To this first presumption in favour of Boulogne we may add another: the ancient authors speak only of a single port on the coast of Gaul nearest to Britain; therefore, they very probably give different names to the same place, among which names figures that of Gesoriacum. Florus374 calls the place where Cæsar embarked the port of the Morini. Strabo375 says that this port was called Itius; Pomponius Mela, who lived less than a century after Cæsar, cites Gesoriacum as the port of the Morini best known;376 Pliny expresses himself in analogous terms.377

Let us now show that the port of Boulogne agrees with the conditions specified in the “Commentaries.”

1. Cæsar, in his first expedition, repaired to the country of the Morini, whence the passage from Gaul to Britain is shortest. Now, Boulogne is actually situated on the territory of that people which, occupying the western part of the department of the Pas-de-Calais, was the nearest to England.

2. In his second expedition, Cæsar embarked at the port Itius, which he had found to offer the most convenient passage for proceeding to Britain, distant from the continent about thirty Roman miles. Now, even at the present day, it is from Boulogne that the passage is easiest to arrive in England, because the favourable winds are more frequent than at Wissant and Calais. As to the distance of about thirty miles (forty-four kilometres), Cæsar gives it evidently as representing the distance from Britain to the Portus Itius: it is exactly the distance from Boulogne to Dover, whereas Wissant and Calais are farther from Dover, the one twenty, the other twenty-three Roman miles.

3. To the north, at eight miles’ distance from the Portus Itius, existed another port, where the cavalry embarked. Boulogne is the only port on this coast at eight miles from which, towards the north, we meet with another, that of Ambleteuse. The distance of eight miles is exact, not as a bird flies, but following the course of the hills. To the north of Wissant, on the contrary, there is only Sangatte or Calais. Now Sangatte is six Roman miles from Wissant, and Calais eleven.

4. The eighteen ships of the upper port were prevented by contrary winds from rallying the fleet at the principal port. We understand easily that these ships, detained at Ambleteuse by winds from the south-west or west-south-west, which prevail frequently in the Channel, were unable to rally the fleet at Boulogne. As to the two ships of burthen, which, at the return of the first expedition, could not make land in the same port as the fleet, but were dragged by the current more to the south, nothing is said in the “Commentaries” which would show that they entered a port; it is probable, indeed, that they were driven upon the shore. Nevertheless, it is not impossible that they may have landed in the little fishers’ ports of Hardelot and Camiers. (See Plate 15.)

We see from what precedes that the port of Boulogne agrees with the text of the “Commentaries.” But the peremptory reason why, in our opinion, the port where Cæsar embarked is certainly that of Boulogne, is, that it would have been impossible to prepare elsewhere an expedition against England, Boulogne being the only place which united the conditions indispensable for collecting the fleet and embarking the troops. In fact, it required a port capable of containing either eighty transport ships and galleys, as in the first expedition, or 800 ships, as in the second; and extensive enough to allow the ships to approach the banks and embark the troops in a single tide. Now these conditions could only be fulfilled where a river sufficiently deep, flowing into the sea, formed a natural port; and, on the part of the coasts nearest to England, we find only at Boulogne a river, the Liane, which presents all these advantages. Moreover, it must not be forgotten, all the coast has been buried in sand. It appears that it is not more than a century and a half that the natural basin of Boulogne has been partly filled; and, according to tradition and geological observations, the coast advanced more than two kilomètres, forming two jetties, between which the high tide filled the valley of the Liane to a distance of four kilomètres inland.

None of the ports situated to the north of Boulogne could serve as the basis of Cæsar’s expedition, for none could receive so great a number of vessels, and we cannot suppose that Cæsar would have left them on the open coast, during more than a month, exposed to the tempests of the ocean, which were so fatal to him on the coasts of Britain.

Boulogne was the only point of the coast where Cæsar could place in safety his depôts, his supplies, and his spare stores. The heights which command the port offered advantageous positions for establishing his camps,378 and the little river Liane allowed him to bring with ease the timber and provisions he required. At Calais he would have found nothing but flats and marshes, at Wissant nothing but sands, as indicated by etymology of the word (white sand).

It is worthy of remark, that the reasons which determined Cæsar to start from Boulogne were the same which decided the choice of Napoleon I. in 1804. In spite of the difference in the times and in the armies, the nautical and practical conditions had undergone no change. “The Emperor chose Boulogne,” says M. Thiers, “because that port had long been pointed out as the best point of departure of an expedition directed against England; he chose Boulogne, because its port is formed by the little river Liane, which allowed him, with some labour, to place in safety from 1,200 to 1,300 vessels.”

We may point out, as another similarity, that certain flat boats, constructed by order of the Emperor, had nearly the same dimensions as those employed by Cæsar. “There required,” says the historian of the ‘Consulate and the Empire,’ “boats which would not need more, when they were laden, than seven or eight feet of water to float, and which would go with oars, so as to pass, either in calm or fog, and strand without breaking on the flat English shores. The great gun-boats carried four pieces of large bore, and were rigged like brigs, that is, with two masts, manœuvred by twenty-four sailors, and capable of carrying a company of a hundred men, with its staff, and its arms and munitions… These boats offered a vexatious inconvenience, that of falling to the leeward, that is, yielding to the currents. This was the result of their clumsy build, which presented more hold to the water than their masts to the wind.”379

Cæsar’s ships experienced the same inconvenience, and, drawn away by the currents in his second expedition, they went to the leeward rather far in the north.

We have seen that Cæsar’s transport boats were flat-bottomed, that they could go either with sails or oars; carry if necessary 150 men, and be loaded and drawn on dry ground with promptness (ad celeritatem onerandi subductionesque). They had thus a great analogy with the flat-bottomed boats of 1804. But there is more, for the Emperor Napoleon had found it expedient to imitate the Roman galleys. “He had seen the necessity,” says M. Thiers, “of constructing boats still lighter and more movable than the preceding, drawing only two or three feet of water, and calculated for landing anywhere. They were large boats, narrow, sixty feet long, having a movable deck which could be laid or withdrawn at will, and were distinguished from the others by the name of pinnaces. These large boats were provided with sixty oars, carried at need a light sail, and moved with extreme swiftness. When sixty soldiers, practised in handling the oar as well as the sailors, set them in motion, they glided over the sea like the light boats dropped from the sides of our great vessels, and surprised the eye by the rapidity of their course.”

The point of landing has been equally the subject of a host of contrary suppositions. St. Leonards, near Hastings, Richborough (Rutupiœ), near Sandwich, Lymne, near Hythe, and Deal, have all been proposed.

The first of these localities, we think, must be rejected, for it answers none of the conditions of the relation given in the “Commentaries,” which inform us that, in the second expedition, the fleet sailed with a gentle wind from the south-west. Now, this is the least favourable of all winds for taking the direction of Hastings, when starting from the coasts of the department of the Pas-de-Calais. In this same passage, Cæsar, after having been drawn away from his course during four hours of the night, perceived, at daybreak, that he had left Britain to his left. This fact cannot possibly be explained if he had intended to land at St. Leonards. As to Richborough, this locality is much too far to the north. Why should Cæsar have gone so far as Sandwich, since he could have landed at Walmer and Deal? Lymne, or rather Romney Marsh, will suit no better. This shore is altogether unfit for a landing-place, and none of the details furnished by the “Commentaries” can be made to suit it.380

There remains Deal; but before describing this place, we must examine if, on his first passage, when Cæsar sailed, after remaining five days opposite the cliffs of Dover, the current of which he took advantage carried him towards the north or towards the south. (See Page 177.) Two celebrated English astronomers, Halley and Mr. Airy, have studied this question; but they agree neither on the place where Cæsar embarked, nor on that where he landed. We may, nevertheless, arrive at a solution of this problem by seeking the day on which Cæsar landed. The year of the expedition is known by the consulate of Pompey and Crassus – it was the year 699. The month in which the departure took place is known by the following data, derived from the “Commentaries;” the fine season was near its end, exuigua parte œstatis reliqua (IV. 20); the wheat had been reaped everywhere, except in one single spot, omni ex reliquis partibus demesso frumento, una pars erat reliqua (IV. 32); the equinox was near at hand, propinqua die œquinoctii (IV. 36). These data point sufficiently clearly to the month of August. Lastly, we have, relative to the day of landing, the following indications: – After four days past since his arrival in Britain… there arose suddenly so violent a tempest… That same night it was full moon, which is the period of the highest tides of the ocean, Post diem quartam, quam est in Britanniam ventum(381)… tanta tempestas subita coorta est… Eadem nocte accidit, ut esset luna plena, qui dies maritimos æstus maximos in Oceano efficere consuevit.

According to this, we consider that the tempest took place after four days, counted from the day of landing; that the full moon fell on the following night; and lastly, that this period coincided not with the highest tide, but with the highest tides of the ocean. Thus we believe that it would be sufficient for ascertaining the exact day of landing, to take the sixth day which preceded the full moon of the month of August, 699; now this phenomenon, according to astronomical tables, happened on the 31st, towards three o’clock in the morning. On the eve, that is, on the 30th, the tempest had occurred; four full days had passed since the landing; this takes us back to the 25th. Cæsar then landed on the 25th of August. Mr. Airy, it is true, has interpreted the text altogether differently from our explanation: he believes that the expression post diem quartum may be taken in Latin for the third day; on another hand, he doubts if Cæsar had in his army almanacks by which he could know the exact day of the full moon; lastly, as the highest tide takes place a day and a half after the full moon, he affirms that Cæsar, placing these two phenomena at the same moment, must have been mistaken, either in the day of the full moon, or in that of the highest tide; and he concludes from this that the landing may have taken place on the second, third, or fourth day before the full moon.

Our reasoning has another basis. Let us first state that at that time the science of astronomy permitted people to know certain epochs of the moon, since, more than a hundred years before, during the war against Perseus, a tribune of the army of Paulus Æmilius announced on the previous day to his soldiers an eclipse of the moon, in order to counteract the effect of their superstitious fears.382 Let us remark also, that Cæsar, who subsequently reformed the calendar, was well informed in the astronomical knowledge of his time, already carried to a very high point of advance by Hipparchus, and that he took especial interest in it, since he discovered, by means of water-clocks, that the nights were shorter in Britain than in Italy.

Everything, then, authorises us in the belief that Cæsar, when he embarked for an unknown country, where he might have to make night marches, must have taken precautions for knowing the course of the moon, and furnished himself with calendars. But we have put the question independently of these considerations, by seeking among the days which preceded the full moon of the end of August, 699, which was the one in which the shifting of the currents of which Cæsar speaks could have been produced at the hour indicated in the “Commentaries.”

Supposing, then, the fleet of Cæsar at anchor at a distance of half a mile opposite Dover, as it experienced the effect of the shifting of the currents towards half-past three o’clock in the afternoon, the question becomes reduced to that of determining the day of the end of the month of August when this phenomenon took place at the above hour. We know that in the Channel the sea produces, in rising and falling, two alternate currents, one directed from the west to the east, called flux (flot), or current of the rising tide; the other directed from the east to the west, named reflux (jusant), or current of the falling tide. In the sea opposite Dover, at a distance of half a mile from the coast, the flux begins usually to be sensible two hours before high tide at Dover, and the reflux four hours after.

So that, if we find a day before the full moon of the 31st of August, 699, on which it was high tide at Dover, either at half-past five in the afternoon or at midday, that will be the day of landing; and further, we shall know whether the current carried Cæsar towards the east or towards the west. Now, we may admit, according to astronomical data, that the tides of the days which preceded the full moon of the 31st of August, 699, were sensibly the same as those of the days which preceded the full moon of the 4th of September, 1857; and, as it was the sixth day before the full moon of the 4th of September, 1857, that it was high tide at Dover towards half-past five in the afternoon (see the Annuaire des Marées des Côtes de France for the year 1857),383 we are led to conclude that the same phenomenon was produced also at Dover on the sixth day before the 31st of August, 699; and that it was on the 25th of August that Cæsar arrived in Britain, his fleet being carried forward by the current of the rising tide.

This last conclusion, by obliging us to seek the point of landing to the north of Dover, constitutes the strongest theoretic presumption in favour of Deal. Let us now examine if Deal satisfies the requirements of the Latin text.

The cliffs which border the coasts of England towards the southern part of the county of Kent form, from Folkestone to the castle of Walmer, a vast quarter of a circle, convex towards the sea, abrupt on nearly all points; they present several bays or creeks, as at Folkestone, at Dover, at St. Margaret’s, and at Oldstairs, and, diminishing by degrees in elevation, terminate at the castle of Walmer. From this point, proceeding towards the north, the coast is flat, and favourable for landing on an extent of several leagues.

The country situated to the west of Walmer and Deal is itself flat as far as the view can reach, or presents only gentle undulations of ground. We may add that it produces, in great quantities, wheat of excellent quality, and that the nature of the soil leads us to believe that it was the same at a remote period. These different conditions rendered the shore of Walmer and Deal the best place of landing for the Roman army.

Its situation, moreover, agrees fully with the narrative of the “Commentaries.” In the first expedition, the Roman fleet, starting from the cliffs of Dover and doubling the point of the South Foreland, may have made the passage of seven miles in an hour; it would thus have come to anchor opposite the present village of Walmer. The Britons, starting from Dover, might have made a march of eight kilomètres quickly enough to oppose the landing of the Romans. (See Plate 16.)

The combat which followed was certainly fought on the part of the shore which extends from Walmer Castle to Deal. At present the whole extent of this coast is covered with buildings, so that it is impossible to say what was its exact form nineteen centuries ago; but, from a view of the locality, we can understand without difficulty the different circumstances of the combat described in Book IV. of the “Commentaries.”

Four days completed after the arrival of Cæsar in Britain, a tempest dispersed the eighteen ships which, after quitting Ambleteuse, had arrived just within sight of the Roman camp. All the sailors of the Channel who have been consulted believe it possible that the same hurricane, according to the text, might have driven one part of the ships towards the South Foreland and the other part towards the coast of Boulogne and Ambleteuse. The conformation of the ground itself indicates the site of the Roman camp on the height where the village of Walmer rises. It was situated there at a distance of 1,000 or 1,200 mètres from the beach, in a position which commanded the surrounding country. And it is thus easy to understand, from the aspect of the locality, the details relative to the episode of the 7th legion, surprised while it was mowing.384 It might be objected that at Deal the Roman camp was not near to a water-course, but they could dig wells, which is the only method by which the numerous population of Deal at the present day obtain water.

From all that has just been said, the following facts appear to us to be established in regard to the first expedition. Cæsar, after causing all his flotilla to go out of the port the day before, started in the night between the 24th and 25th of August, towards midnight, from the coast of Boulogne, and arrived opposite Dover towards six o’clock in the morning. He remained at anchor until half-past three in the afternoon, and then, having wind and tide in his favour, he moved a distance of seven miles and arrived near Deal, probably between Deal and Walmer Castle, at half-past four. As in the month of August twilight lasts till after half-past seven, and its effect may be prolonged by the moon, which at that hour was in the middle of the heaven, Cæsar had still four hours left for landing, driving back the Britons, and establishing himself on the British soil. As the sea began to ebb towards half-past five, this explains the anecdote of Cæsius Scæva told by Valerius Maximus; for, towards seven o’clock, the rocks called the Malms might be left uncovered by the ebb of the tide.

After four entire days, reckoned from the moment of landing, that is, on the 30th of August, the tempest arose, and full moon occurred in the following night.

This first expedition, which Cæsar had undertaken too late in the season, and with too few troops, could not lead to great results. He himself declares that he only sought to make an appearance in Britain. In fact, he did not remove from the coast, and he left the island towards the 17th of September, having remained there only twenty-three days.385

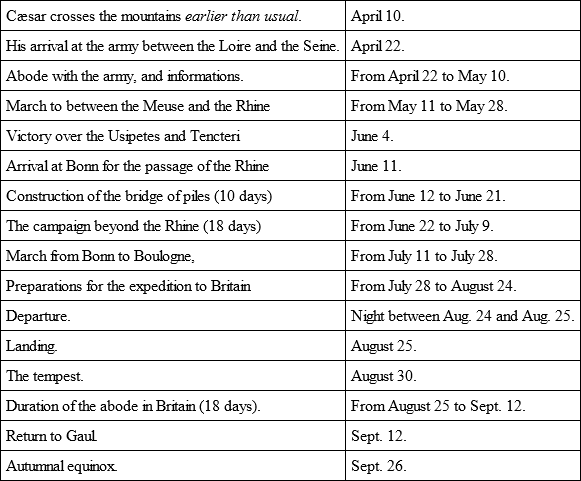

Résumé of the Dates of the Campaign of 699.

IX. We recapitulate as follows the probable dates of the campaign of 699: —

CHAPTER VIII

(Year of Rome 700.)

(Book V. of the “Commentaries.”)MARCH AGAINST THE TREVIRI – SECOND DESCENT IN BRITAINInspection of the Fleet. March against the Treviri.

I. CÆSAR, after having appeased the troubles of Illyria, and passed some time in Italy, rejoined the army in the country of the Belgæ, at the beginning of June in the year 700. Immediately on his arrival, he visited all his quarters, and the naval arsenal established, according to Strabo, at the mouth of the Seine.386 He found his fleet ready for sea. In spite of the scarcity of necessary materials, the soldiers had laboured in building it with the greatest zeal. He rewarded them with commendations, complimented those who had directed the works, and appointed for the general rendezvous the Portus Itius (Boulogne).

The concentration of the fleet required a considerable length of time, of which Cæsar took advantage to prevent the effects of the agitation which had shown itself among the Treviri. These populations, rebelling against his orders, and suspected of having called the Germans from beyond the Rhine, did not send their representatives to the assemblies. Cæsar marched against them with four legions, without baggage, and 800 cavalry, and left troops in sufficient number to protect the fleet.

The Treviri possessed, in addition to a considerable infantry, a more numerous cavalry than any other people in Gaul. They were divided into two factions, whose chiefs, Indutiomarus and his son-in-law Cingetorix, disputed the chief power. The latter was no sooner informed of the approach of the legions, than he repaired to Cæsar, and assured him that he would not fail in his duties towards the Roman people. Indutiomarus, on the contrary, raised troops, and caused to be placed in safety, in the immense forest of the Ardennes, which extended across the country of the Treviri from the Rhine to the territory of the Remi, all those whose age rendered them incapable of carrying arms. But when he saw several chiefs (principes), drawn by their alliance with Cingetorix or intimidated by the approach of the Romans, treat with Cæsar, fearing to be abandoned by all, he made his submission. Although Cæsar put no faith in his sincerity, yet, as he did not want to pass the fine season among the Treviri, and as he was desirous of hastening to Boulogne, where all was ready for the expedition into Britain, he was satisfied with exacting 200 hostages, among whom were the son and all the kindred of Indutiomarus, and, after having assembled the principal chiefs, he conferred the authority on Cingetorix. This preference accorded to a rival turned Indutiomarus into an irreconcileable enemy.387

Departure for the Isle of Britain.

II. Hoping that he had pacified the country by these measures, Cæsar proceeded with his four legions to the Portus Itius. His fleet, perfectly equipped, was ready to sail. Including the vessels of the preceding years, it was composed of six hundred transport ships and twenty-eight galleys. It wanted only forty ships built in the country of the Meldæ,388 which a tempest had driven back to their point of departure; adding to it a certain number of light barques which many chiefs had caused to be built for their own personal usage, the total amounted to 800 sail.389 The Roman army concentrated at Boulogne consisted of eight legions and 4,000 cavalry raised in the whole of Gaul and in Spain;390 but the expeditionary body was composed only of five legions and 2,000 cavalry. Labienus received orders to remain on the coast of the Channel with three legions, and one-half of the cavalry, to guard the ports, provide for the supply of the troops, keep watch upon Gaul, and act according to circumstances. Cæsar had convoked the principal citizens, of each people (principes ex omnibus civitatibus), and left upon the continent but the small number of those of whose fidelity he was assured, taking with him the others as pledges of tranquillity during his absence. Dumnorix, who commanded the Æduan cavalry in the expedition, was of all the chiefs the one it was most important to carry with him. Restless, ambitious, and distinguished by his courage and credit, this man had tried every means in vain to obtain permission to remain in his country. Irritated by the refusal, he became a conspirator, and said openly that Cæsar only dragged the nobles into Britain to sacrifice them. These plots were known and watched with care.