полная версия

полная версияHistory of Julius Caesar Vol. 1 of 2

665

Velleius Paterculus, II. 6, 15. – Plutarch, C. Gracchus, 7, 8.

666

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 19 et seq.

667

Plutarch, C. Gracchus, 9. – Appian, Civil Wars, I. 23.

668

Sallust, Jugurtha, 27. – Cicero, Oration on the Consular Provinces, 2, 15; Oration for Balbus, 27.

669

Cicero, Oration for Rabirius, 4.

670

Plutarch, C. Gracchus, 7, 12. – According to Velleius Paterculus (II. 6), “he would have extended this right to all the peoples of Italy as far as the Alps.”

671

Pseudo-Sallust, First Letter to Cæsar, vii. – Titus Livius, XXVI. 22.

672

“Aut censoria locatio constituta est, ut Asiæ, lege Sempronia.” Cicero, Second Prosecution of Verres, III. – See, on this question, Mommsen, Inscriptiones Latinæ Antiquissimæ, pp. 100, 101.

673

In the province, the domain of the soil belongs to the Roman people; the proprietor is reputed to have only the possession or usufruct. (Gaius, Institutes, II. 7.)

674

The senators were reproached with the recent examples of prevarication given by Cornelius Cotta, by Salinator, and by Manius Aquilius, the conqueror of Asia.

675

Yet the Epitome of Titus Livius (LX.) speaks of 600 knights instead of 300. (See Pliny, Natural History, XXXIII. 7. – Appian, Civil Wars, I. 22. – Plutarch, C. Gracchus, 7.)

676

Plutarch, C. Gracchus, 12.

677

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 24.

678

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 17.

679

“I am not one of those consuls who think that it is a crime to praise in the Gracchi, as magistrates whose counsels, wisdom, and laws carried a salutary reform into many parts of the administration.” (Cicero, Second Speech on the Agrarian Law, 5.)

680

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 27.

681

Sallust, Jugurtha, 31.

682

Sallust, Jugurtha, 5.

683

“Marius had only made his temper more unyielding.” (Plutarch, Sylla, 39.) – “Talent, probity, simplicity, profound knowledge of the art of war, Marius joined to the same degree the contempt of riches and pleasures with the love of glory.” (Sallust, Jugurtha, 63.) – Marius was born on the territory of Arpinum, at Cereatæ, now Casamari (the house of Marius).

684

“Obtained the esteem of both parties.” (Plutarch, Marius, 4.)

685

Sallust, Jugurtha, 85.

686

Plutarch, Marius, 10.

687

Plutarch, Marius, 19.

688

Plutarch, Marius, 11.

689

Plutarch, Marius, 28.

690

Plutarch, Marius, 29.

691

Titus Livius, XXIII. 22.

692

In our opinion, bellum sociale, or sociorum, has been wrongly translated by “social war,” an expression which gives a meaning entirely contrary to the nature of this war.

693

Velleius Paterculus, II. 15.

694

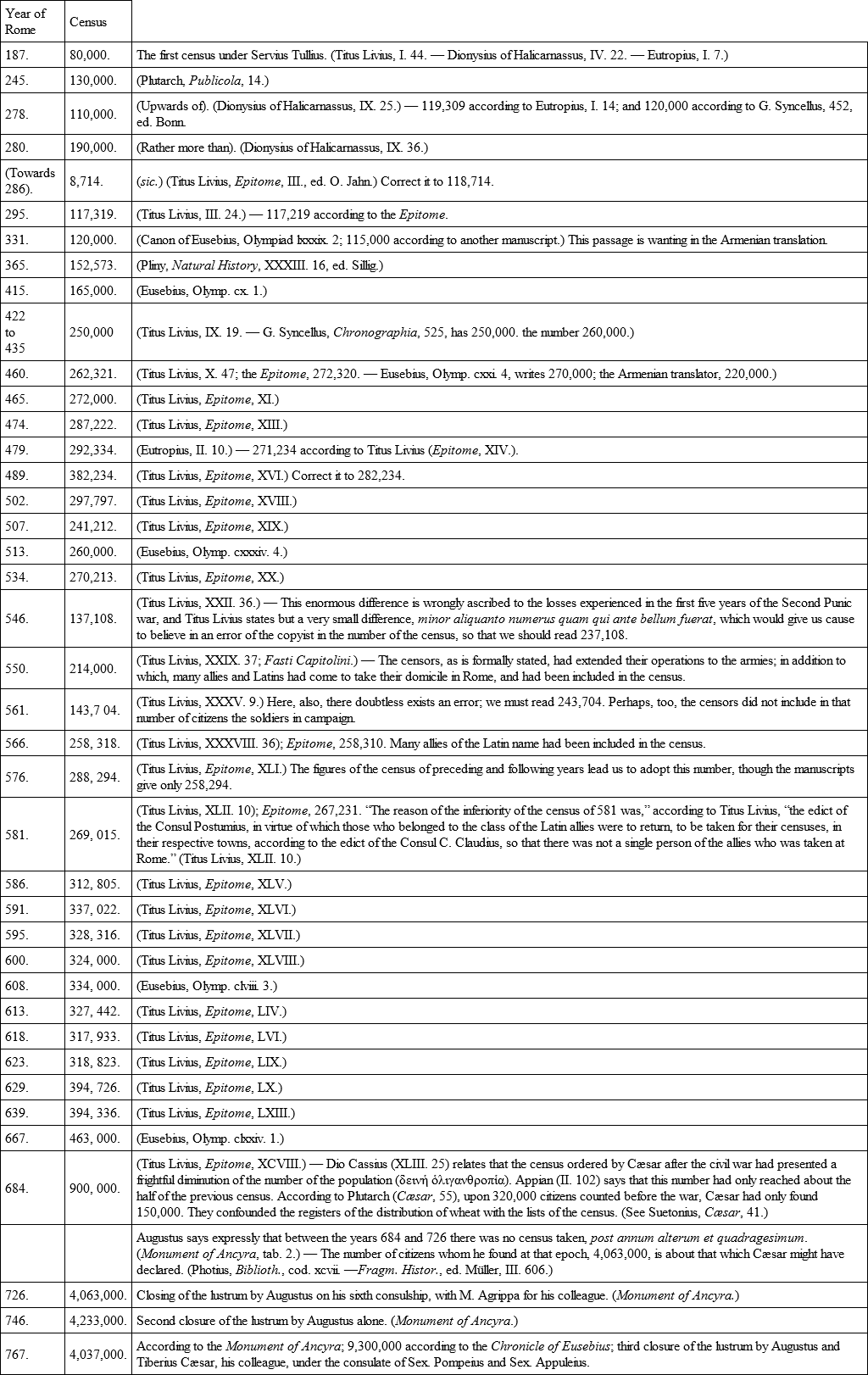

List of the different Censuses: —

695

These two words are found on the Italiote medals struck during the war. A denarius in the Bibliothèque Impériale presents the legend ITALIA in Latin characters, and, on the reverse, the name of Papius Mutilus in Oscan characters: Gai, PAAPI + G (ai fili).

696

This measure satisfied the Etruscans. (Appian, Civil Wars, I. 49.)

697

Velleius Paterculus, II. 20. – Appian, Civil Wars, I. 49.

698

See Note (^1) to page 226.

699

“P. Sulpicius had sought by his rectitude the popular esteem: his eloquence, his activity, his mental superiority, and his fortune, made of him a remarkable man.” (Velleius Paterculus, II. 18.)

700

Plutarch, Marius, 36.

701

Plutarch, Sylla, 11.

702

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 57.

703

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 59. “Populus Romanus, Lucio Sylla dictatore ferente, comitiis centuriatis, municipiis civitatem ademit.” (Cicero, Speech for his House, 30.)

704

“In conferring upon the peoples of Italy the right of Roman city, they had been distributed into eight tribes, in order that the strength and number of these new citizens might not encroach upon the dignity of the old ones, and that men admitted to this favour might not become more powerful than those who had given it to them. But Cinna, following in the steps of Marius and Sulpicius, announced that he should distribute them in all the tribes; and, on this promise, they arrived in crowds from all parts of Italy.” (Velleius Paterculus, II. 20.)

705

Velleius Paterculus, II. 20.

706

Plutarch, Pompeius, 3.

707

Plutarch, Sertorius, 5.

708

“Cinna counted on that great multitude of new Romans, who furnished him with more than three hundred cohorts, divided into thirty legions. To give the necessary credit and authority to his faction, he recalled the two Marii and the other exiles.” (Velleius Paterculus, II. 20.)

709

Quod parcius telum recepisset. This expression appears to be borrowed from the combats of gladiators, which derived their origin from similar human sacrifices performed at the funerals. (See Cicero, Speech for Roscius Amerinus, 12. – Valerius Maximus, IX. xi. 2.)

710

Plutarch, Sylla, 6.

711

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 77.

712

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 79.

713

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 95.

714

Velleius Paterculus, II. 27. The Samnites thus designated the Romans, in allusion to the wolf, the nurse of the founder of Rome. A Samnite medal represents the bull, the symbol of Italy, throwing the wolf to the ground. It bears the name of C. Papius Mutilus, with the title Embratur, an Oscan word corresponding to the Latin imperator.

715

“Thus terminated two most disastrous wars: the Italic, called also the Social War, and the Civil War; they had lasted together ten years; they had mown down more than a hundred and fifty thousand men, of whom twenty-four had been consuls, seven prætors, sixty ediles, and nearly two hundred senators.” (Eutropius, V. 6.)

716

“Sylla fomented these disorders by loading his troops with largesses and profusions without bounds, in order to corrupt and draw to him the soldiers of the opposite parties.” (Plutarch, Sylla, 16.)

717

Dio Cassius (XXXIV. cxxxvi. § 1) gives the number as 8,000; Appian as 3,000. Valerius Maximus speaks of three legions (IX. 2, § 1).

718

“A great number of allies and Latins were deprived by one man of the right of city, which had been given to them for their numerous and honourable services.” (Speech of Lepidus, Sallust, Fragm., I. 5.) – “We have seen the Roman people, at the proposal of the dictator Sylla, take, in the comitia of centuries, the right of city from several municipal towns; we have seen it also depriving them of the lands they possessed… As to the right of city, the interdiction did not last even so long as the military despotism of the dictator.” (Cicero, Speech for his House, 30.)

719

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 95. – Velleius Paterculus, II. 28.

720

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 95.

721

Strabo, V. iv. 207.

722

Dio Cassius, XXXIV. 137, § 1.

723

Dio Cassius, XXXIV. 137.

724

Valerius Maximus, IX. ii. 1.

725

Plutarch, Cato of Utica, 21.

726

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 96. – Titus Livius, Epitome, LXXXIX.

727

Appian, I. 100. – Velleius Paterculus, II. 31. – The auxilium was the protection accorded by the tribune of the people to whoever claimed it.

728

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 100 et seq.

729

Appian, Civil Wars, I. (See, on an inscription raised by the freedmen in honour of the dictator, and which has been discovered in Italy, Mommsen, Inscriptiones Latinæ Antiquissimæ, p. 168.)

730

Titus Livius, Epitome, LXXXIX.

731

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 100.

732

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 100. – In 574, the age required for the different magistracies had already been fixed. (Titus Livius, XL. 44.)

733

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 101. – Titus Livius, Epitome, LXXXIX.

734

Aulus Gellius, II. 24.

735

Cicero, Familiar Letters, III. 6, 8, 10.

736

Titus Livius, Epitome, LXXXIX. – Tacitus, Annals, XI. 22. – Aurelius Victor, Illustrious Men, lxxv.

737

Cicero, De Oratore, II. 39. – “A law which, among the ancients, embraced different objects: treasons in the army, seditions at Rome, diminution of the majesty of the Roman people by the bad administration of a magistrate.” (Tacitus, Annals, I. 72.)

738

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 104.

739

He waited the death of the dictator to rob the treasury of a sum which he owed to the State. (Plutarch, Sylla, 46.)

740

Appian, Civil Wars, I. 106.

741

Sylla had taken the name of Fortunate (Felix). (Mommsen, Inscriptiones Latinæ Antiquissimæ, p. 168), or of Faustus, according to Velleius Paterculus.

742

“It cannot be denied that Sylla had then the power of a king, although he had restored the Republic.” (Cicero, Speech on the Report of the Aruspices, 25.)

743

The celebrated German author, Mommsen (Roman History, III. 15), does not admit this date of 654. He proposes, under correction, the date of 652, for the reason that the ages required for the higher offices of State, since Sylla’s time, were thirty-seven for the edileship, forty for the prætorship, forty-three for the consulship, and as Cæsar was curule ædile in 689, prætor in 692, consul in 695, he would, had he been born in 654, have filled each of these offices two years before the legal age.

This objection, certainly of some force, is dispelled by other historical testimony. Besides, we know that at Rome they did not always observe the laws when dealing with eminent men. Lucullus was raised to be chief magistrate before the required age, and Pompey was consul at thirty-four. (Appian, Civil Wars, I. 14.) – Tacitus speaks on this matter thus: “With our ancestors this magistracy (the questorship) was the prize of merit only, for every citizen of ability had then the right to aim at these honours; even age was so little regarded, that extreme youth did not exclude from either the consulship or the dictatorship.” (Annals, XI. 22.) – In any case, if the opinion of M. Mommsen be adopted, the birth of Cæsar must be referred to 651, not 652. For, if he was born in the month of July, 652, he could only be forty-three years of age in the month of July, 695; and as the nomination of the consuls preceded by six months their entering into office, it would be in the month of July, 694, when he would have attained the legal age, which would bring the date of his birth to the year 651. But Plutarch (Cæsar, 69), Suetonius (Cæsar, 88), and Appian (Civil Wars, II. 149) all agree in saying that Cæsar was fifty-six when he was assassinated on the 15th of March, 710, which fixes his birth in the year 654. On the other hand, according to Velleius Paterculus (II. 43), Cæsar was appointed flamen of Jupiter by Marius and Cinna when scarcely out of infancy, and at Rome infancy ended at about fourteen; and the consulship of Marius and Cinna being in 668, Cæsar, according to our calculation, would then, in fact, have entered on his fourteenth year. The same author adds that he was about eighteen in 672, when he left Rome to escape the proscriptions of Sylla, a new reason for retaining the preceding date.

Cæsar made his first campaign in Asia, at the taking of Mitylene, in 674 (Titus Livius, Epitome, LXXXIX.), which makes him twenty at the date of his entrance into the service. According to Sallust (Catilina, 49), when Cæsar was nominated grand pontiff in competition with Catulus, he was almost a youth (adolescentulus); and Dio Cassius says the same, in nearly the same terms. Doubtless they expressed themselves thus because of the great disproportion in the age of the two candidates. The expression of these authors, although unfitting, nevertheless agrees better with our reckoning, which ascribes thirty-seven years of age to Cæsar, than to the other, which gives him thirty-nine. Tacitus also, as we shall see in a note to a subsequent page, when speaking of the accusation against Dolabella, tends to make Cæsar too young rather than too old.

744

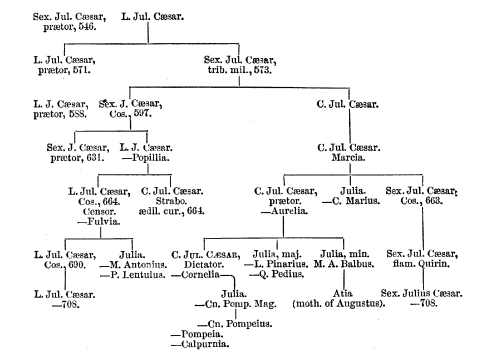

The family of the Julii was very ancient, and we find personages bearing this name from the third century of Rome. The first of whom history makes mention was C. Julius Julus, consul in 265. There were other consuls of the same family in 272, 281, 307, 324; consular tribunes in 330, 351, 362, 367; and a dictator, C. Julius Julus, in 402; but their filiation is little known. The genealogy of Cæsar begins in a direct line only from Sextus Julius Cæsar, prætor in 546. We borrow the genealogy of the family of the Julii from the History of Rome by Families, by the learned professor W. Drumann (Vol. III., page 120; Kœnigsberg, 1837), introducing one variation only, explained in Note (4) of page 290.

The opinion most accredited with the ancients, on the origin of the name of Cæsar, was that Julius slew an elephant in a fight. In the Punic tongue cæsar signifies “an elephant.” The medals of Cæsar, as grand pontiff, confirm this hypothesis; on the reverse is an elephant crushing a serpent beneath its feet. (Cohen, Consular Medals, plate xx. 10.) – We know that some symbols on the Roman medals are a species of canting heraldry. Pliny gives another etymology of the name of Cæsar: “Primusque Cæsarum a cæso matris utero dictus, qua de causa et Cæsones appellati.” (Natural History, VII. 9.) – Festus (p. 57) thus expresses himself: “Cæsar a cæsarie dictus est; qui scilicet cum cæsarie natus est;” and page 45: “Cæsariati (comati).” – Finally, Spartianus (Life of Ælius Verus, ii.) sums up in these words the greater part of the etymologies: “Cæsorem vel ab elephante (qui lingua Mauroram cæsar dicitur) in prœlio cæso, cum qui primus sic appellatus est, doctissimi et eruditissimi viri putant dictum; vel quia mortua matre, ventre cæso sit natus; vel quod cum magnis crinibus sit utero parentis effusus; vel quod oculis cæsiis et ultra humanum morem viguerit.” (See Isidore, Origines, IX. iii. 12. – Servius, Commentary on the Æneid, I. 290, and Constantine Manasses, p. 71.)

745

Pliny, Natural History, VII. 53. – “Cæsar was in his sixteenth year when he lost his father.” (Suetonius, I.)

746

“He sprang from the noble family of the Julii, and, according to an opinion long believed in, he derived his origin from Venus and Anchises.” (Velleius Paterculus, II. 41.)

747

In fact, the gens Marcia, one of the most illustrious patrician families in Rome, reckoned among its ancestors Numa Marcius, who married Pompilia, the daughter of Numa Pompilius, by whom he had Ancus Marcius, who was King of Rome after the death of Tullus Hostilius. (Plutarch, Coriolanus, I; Numa, 26.)

748

Suetonius, Cæsar, vi. This passage, as generally translated, is unintelligible, because the translators render the words Martii Reges by the Kings Martius, instead of the family of Marcius Rex.

749

Plutarch, Cæsar, 10.

750

“So Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi; Aurelia, mother of Cæsar; Atia, mother of Augustus, all presided over the education of their children, we are told, and made them into great men.” (Tacitus, Dialogue concerning Orators, 28.)

751

“Ingenii magni, memoriæ singularis, nec minus Græce quam Latine doctus.” (Suetonius, On Illustrious Grammarians, 7.)

752

“A sermone Græco puerum incipere malo.” (Quintilian, Institution of Oratory, I. i.)

753

Claudius, addressing a foreigner who spoke Greek and Latin, said, “Since thou possessest our two languages.” (Suetonius, Claudius, 42.)

754

Καἱ σὑ, τἑκνον! (Suetonius, Cæsar, 82.)

755

Suetonius, Cæsar, 56.

756

“Still quite young, he seems to have attached himself to the kind of eloquence adopted by Strabo Cæsar, and he has even given, in his Divination, several passages, word for word, of the discourse of this orator for the Sardinians.” (Suetonius, Cæsar, 55.)

757

Aulus Gellius, IV. 16.

758

“For Cæsar and Brutus have also made verses, and have placed them in the public libraries. Poets as feeble as Cicero, but happier than he, in that fewer people knew what they had done.” (Tacitus, Dialogue concerning Orators, 21.)

759

Tu quoque, tu in summis, o dimidiate Menander,Poneris, et merito, puri sermonis amator.Lenibus atque utinam scriptis adjuncta foret visComica, ut æquato virtus polleret honoreCum Græcis; neque in hac despectus parte jaceres!Unum hoc maceror et doleo tibi deesse, Terenti.(Suetonius, Life of Terence, 5.)760

“Liberal to prodigality, and of a courage above human nature and even imagination.” (Velleius Paterculus, II. 41.)

761

“He held, undeniably, the second rank among the orators of Rome.” (Plutarch, Cæsar, 3.)

762

“Nam cui Hortensio, Lucullove, vel Cæsari, tam parata unquam adfuit recordatio, quam tibi sacra mens tua loco momentoque, quo jusseris, reddit omne depositum?” (Latinus Pacatus, Panegyricus in Theodosium, XVIII. 3.) – (Pliny, Natural History, VII. 25.)

763

“Quamvis moderate soleret irasci, maluit tamen non posse.” (Seneca, De Ira, II. 23.)

764

Plutarch, Cæsar, 4.

765

Plutarch, Cæsar, 19.

766

“To the external advantages which distinguished him from all the other citizens, Cæsar joined an impetuous and powerful soul.” (Velleius Paterculus, II. 41.)

767

Suetonius, Cæsar, 15.

768

“By his voice, his gesture, the grand and noble air of his person, he had a certain brilliant manner of speech, without the least artifice.” (Cicero, Brutus, 75; copied by Suetonius, Cæsar, 55.)

769

Plutarch, Cæsar, 18.

770

“From his first youth he was much used to horseback, and had even acquired the facility of riding with dropped reins and his hands joined behind his back.” (Plutarch, Cæsar, 18.)

771

“He ate and slept without enjoying the pleasure of either, and only to obey necessity.” (Velleius Paterculus, II. 41.)

772

Suetonius, Cæsar, 53. – (Plutarch, Cæsar, 18 and 58.)

773

“And when,” says Cicero, “I look at his hair, so artistically arranged; and when I see him scratch his head with one finger, I cannot believe that such a man could conceive so black a design as to overthrow the Roman Republic.” (Plutarch, Cæsar, 4.)

774

Suetonius, Cæsar, 45. – Cicero said likewise, “I suffered myself to be caught by the fashion of his girdle,” alluding to his hanging robe, which gave him an effeminate appearance. (Macrobius, Saturnalia, II. 3.)

775

Dio Cassius, XLIII. 43.

776

Velleius Paterculus, II. 41.

777

Suetonius (Cæsar, 1) says that Cæsar was designated (destinatus) flamen. Velleius Paterculus (II. 43), that he was created flamen. In our opinion he was created, but not inaugurated, flamen. Now, as long as this formality was not accomplished, he was only the flamen designate. What proves that he had never been inaugurated is, that Sylla could revoke it; and, on another hand, Tacitus says (Annales, III. 53) that, after the death of Cornelius Merula, the flamenship of Jupiter remained vacant for seventy-two years, without any interruption to the special worship of this god. So that, evidently, they did not count the flamenship of Cæsar as real, since he had never entered on his office.

778

“Dimissa Cossutia … quæ pretextato desponsata fuerat.” (Suetonius, Cæsar, 1.) – This passage from Suetonius clearly indicates that he was betrothed, and not married, to Cossutia; for Suetonius uses the word dimittere, which means “to free,” and not the word repudiare in its true meaning; besides, desponsata signifies betrothed. – Plutarch says that Cornelia was the first wife of Cæsar, though he pretends that he married Pompeia as his third. (Plutarch, Cæsar, 5.)