Waves Across the South

Another way in which empire was made anew in the age of revolutions was through new classifications of peoples and kinds.[8] Scientific and natural historical classifications were linked with the surveillance regime of the expanding colonial state. The relation between science and colonialism can seem paradoxical; for new sciences were seen in the period as the harbingers of an age of reason. The way people engaged with water, from how they fished, to how they communed with sea creatures, to how they navigated the sea, or the artefacts they used or descriptions of their allegedly nomadic existences, easily led into colonial classifications of race and gender. The possibility of intensive comparison around neighbouring islands and settlements, which imperial writers cast as self-contained sites despite long histories of migration, meant that these oceanic basins became ideal for working through ideas of difference and for policies of segregation.

The consolidation of Britishness and whiteness in the new port cities from Port Louis to Sydney, which symbolised the forward march of this maritime Britannia, depended on sea-facing mariners, alleged pirates and private traders transforming themselves into respectable shore residents with families in situ and under Christian marriage. These colonists moved from itinerant sea-trades to settled interests in land and pasture. The moral duties of white maleness could overtake other ways of organising race and gender near the sea. Sporadic colonisation across the sea, for instance through escaped convicts, missionaries or private traders and slavers was made more ‘systematic’ for instance in New Zealand. The veto power of the slogan of ‘free trade’ was useful here. Maritime patriotism also became part and parcel of this transformation and its forward charge came partly from such enterprises as anti-slavery and anti-piracy and their legacy in more extensive land-based colonial enterprises. Such patriotism is often missed in existing retellings of this era which focus on large continental hinterlands and which point to ‘agrarian patriotism’, the glorification of land and agriculture, as an ideology which supercharged the British advance in the East.[9]

It is fitting, given the setting of this story in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, to describe this contest between revolution and empire as a clash of waves. To think with waves is to think with the push-and-pull dynamic of globalisation. It is to consider the surging advance of connection across the sea as well as turbulent disconnection and violence across waters.[10] It is to contemplate the formation of crests as well as the breaking of waves on the beach. All this was the case for revolution and empire, for both of these were susceptible to breakage and could never come to full success in these decades.

Thinking with waves is also apposite in reminding ourselves that the physical setting of this story matters. The physicality of rain, storms, squalls, cyclones, waterspouts, fevers and earthquakes had to be combatted to make global empire work, through regimes of study, tabulation, mapping, modelling, medicine and urban fortification and planning.[11] The irregular shape of the Earth itself had to be managed to allow ships on the sea to navigate their course and to lubricate free-trade empire, for instance between India and China or Australia. Surveying of the sea and the coastline was a first task that ran ahead of empire at a time when new scientific disciplines were being forged. Such surveying fed into the establishment of bases, transit points, ports and settlements across these oceans as definitions of sovereignty travelled from ship to shore and were transported into the interior.

The sea was not easily passed: ships featured here disappeared, caught fire, exploded, or were tossed into the air together with horses and fighting men, or ran aground in coral reefs. Ships were rebooted after being taken over by warring nations at a time of global war or pirated. In this sense too the ship was an unstable platform. The port city of these oceans was a place of meditation on shipwrecks, as the remains of vessels lined the shore. Water had to be safely navigated for purposes of colonial war, and the intersecting terrain of land, sea and rivers, close to the shore and leading inland, could be deadly for the British in terms of health and given the ill-suitedness of their techniques and logistics of conflict to such terrain. Conflict over water did not automatically privilege Europeans versus non-Europeans, though these two groups were erroneously separated as maritime versus land-based.

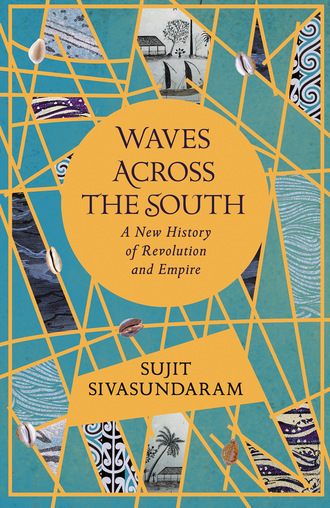

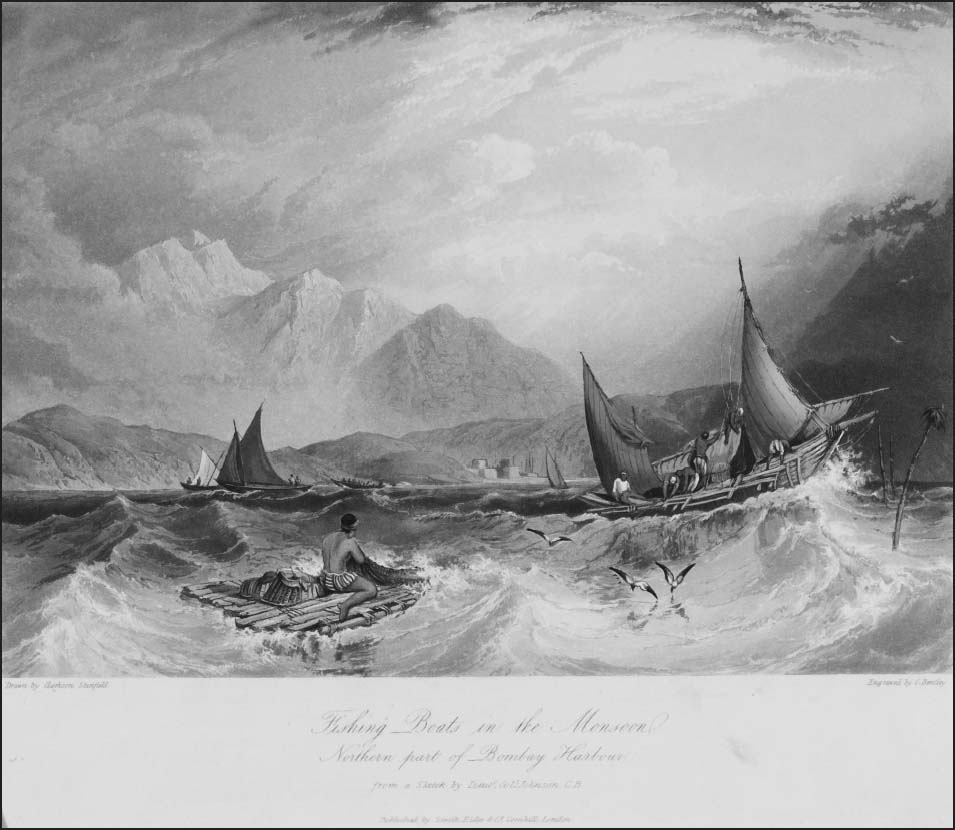

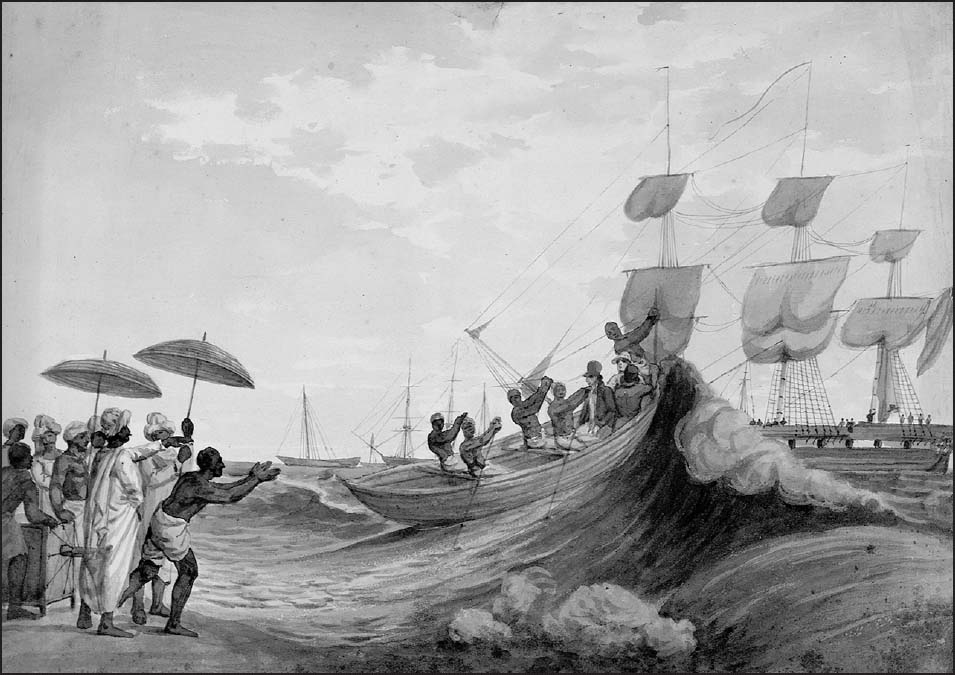

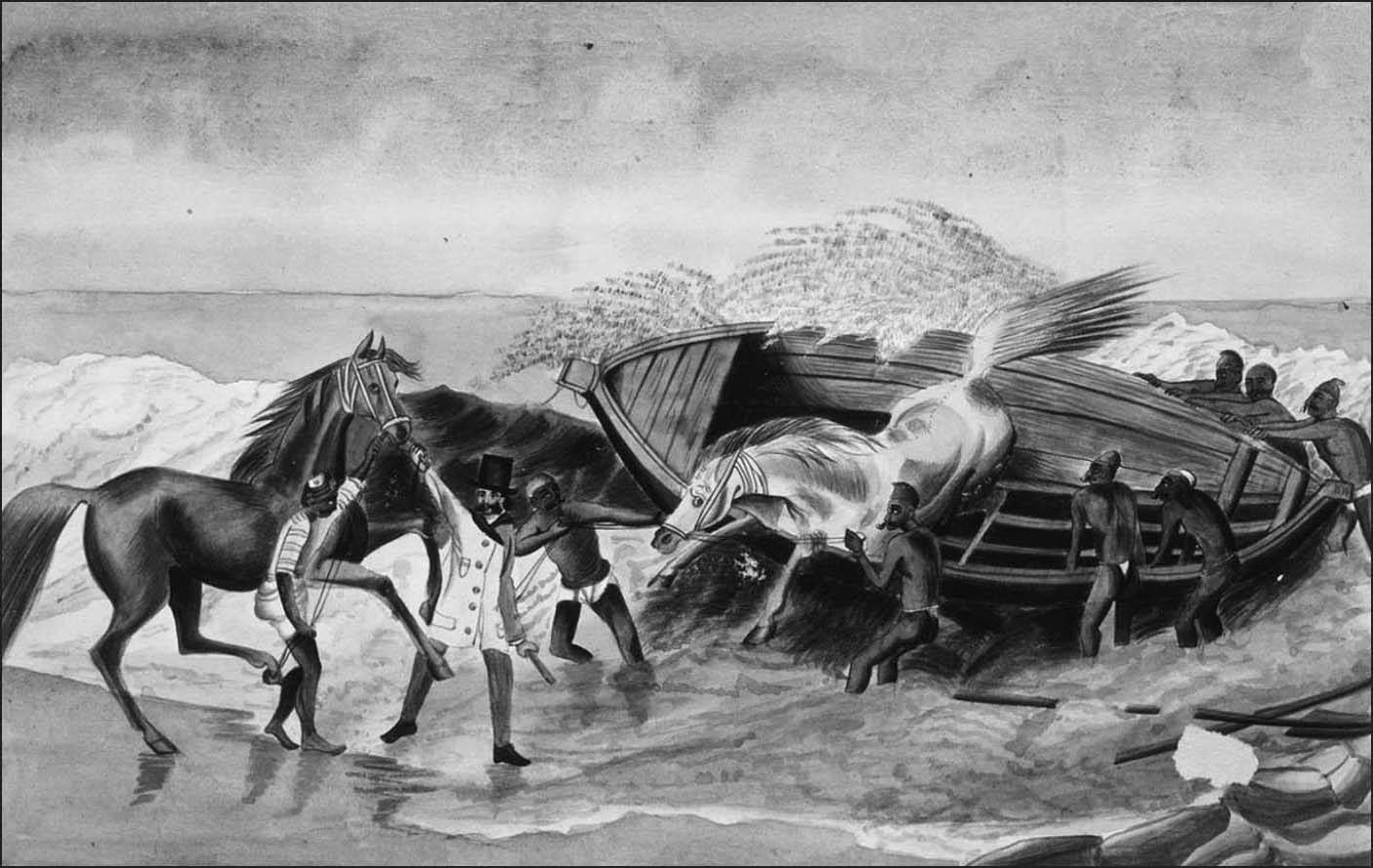

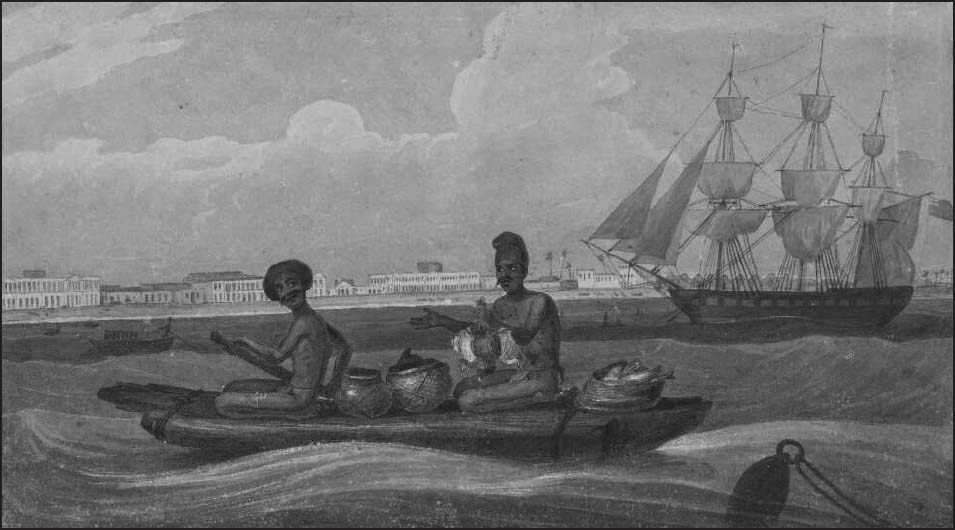

The significance of the physical setting to the history can be seen in some intriguing images. Take, for instance, ‘Fishing Boats in the Monsoon, northern part of Bombay harbour’ (1826), which is right in the middle of the period covered here. [Fig. 0.1] Produced in India, it was based on a sketch by Colonel John Johnson of the Bombay Engineers and shows two Indian craft battling the foaming waves.[12] It was not only fishermen such as those depicted here who used Indian craft. Take another image from another Indian port showing what it took to disembark, ‘Surf boat landing European passengers at Madras’ (c.1800) [Fig. 0.2]. Notably, there are just two Europeans in the foreground of this picture. Britons in red uniform feature in the ship behind. It is the Indians who battle the waves through their labour and this labour is co-opted to make an empire practicable. A good partner image for this one, which is in keeping with the uncharted connections across the Indian and Pacific Oceans in view in this book, is ‘Landing Horses from Australia; Catamarans and Masoolah boat, Madras’ (c.1834) [Fig. 0.3]. Though an incongruous European in hat and beard and jacket stands in the waters, it is the Indians who work with the animals in the boat who make it possible for poor horses to travel across vast distances of water. These images compare Indians with Europeans, but they also demonstrate an interest in Indian craft as well as European vessels. Notice Augustus Earle’s ‘Catamaran on Madras Roads’ [Fig. 0.4].

Fig. 0.1 ‘Fishing Boats in the Monsoon, Northern part of Bombay [Mumbai] Harbour’ (1826)

0.1 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig. 0.2 ‘Surf boats landing European passengers at Madras [Chennai]’, c.1800

0.2 © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

It is the ingenuity of the seafarers of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, so strikingly illustrated in these images, which motivated me to write Waves Across the South. The book takes a chronological journey through these critical decades, from the dramatic voyages in the 1790s to the energetic debates in the press and in civil associations in the burgeoning port cities of the 1840s. As it does this, it tours the misplaced histories of the southern seas in the age of revolutions and follows the rise of the British empire. Along the path from revolution to empire, our travels take into account the meeting of cultures, indigenous and colonial revolt, imperial annexation, conceptions of race and gender, conflict across the seas, global knowledge and the growth of public sentiment around programmes of liberal reform. Each of these seas had separate stories in the age of revolutions but the expansion of the British empire created dense connections between these distant realms.

Fig. 0.3 ‘Landing [Waler] horses from Australia; Catamarans and Masoolah boat’, Madras, c.1834

0.3 © State Library of New South Wales

Fig. 0.4 ‘Catamaran on Madras [Chennai] Roads’, by Augustus Earle, 1829

0.4 © Augustus Earle, National Library of Australia, NK12/126.

Though spanning less than seventy years, these decades sit within a long and brilliant tapestry of history in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. European intrusion appears here as a late entry.

Long-distance voyages undertaken by so-called Austronesians saw the settlement of the vast realms of the Pacific Ocean, including more than 500 islands, from west to east from present-day Taiwan, and beginning from around 6,000 years ago.[13] Much before this, around 65,000 years ago or longer before human beings had migrated from the landmass called Sunda to Sahul, the latter of which linked today’s New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania. Austronesians reached Aotearoa or New Zealand around 1300 CE and the distant foothold of Rapa Nui or Easter Island around 300–400 CE. They travelled in single outrigger or large double-hulled canoes, taking with them water, and fermented breadfruit, which could last for about three months. Sometimes they would take plants that could be grown on landing, and livestock, domesticated pigs, dogs and chickens. Settlers who roamed further into Oceania formed the ‘Lapita’ sphere of settlement; Lapita settlers valued obsidian or glass-like stone and took it to the region of the Pacific which was far distant from Asia. The styles of their pottery spread with them. There was a great deal of migration between these islands. As one archaeologist writes: ‘Within the Lapita sphere you might have met the same man or woman one year in Tonga, and the next on New Britain or in Vanuatu. It would seem that about 3,000 years ago people from New Guinea Islands and out as far as Tonga and Samoa were more interconnected than at any time until the age of mass transportation began some two centuries ago.’[14]

There then arose a triangle of settlement across the vast Pacific, which had as its points Hawai‘i, Rapa Nui and Aotearoa. This zone of settlement is huge; it is about the size of Europe and Asia put together. The ‘Polynesian’ and ‘Micronesian’ systems of navigation aided these successful voyages. The islanders relied on star positions at night and the sun during the day, the speed of wind and current, the swell of the sea caused by different kinds of winds, and the signs of birds and other natural elements. They waited for the right winds. They calculated their position by dead reckoning. But from about 1300, voyages became less frequent, and a series of islands in the triangle were abandoned. It was into an intricate world of shared language and politics that early modern European voyagers arrived: Spanish, Portuguese, English and French. And it was these voyages which once again reconnected indigenous peoples across the wide span of Oceania. Islanders recalled their historic migrations. The vibrant non-European politics of the seventy years covered in this book were shaped by these memories and the renewed connections with oceanic neighbours that European vessels brought.

The Indian Ocean too was long known from multiple cultural perspectives.[15] Coastal and regional trade was well established prior to the common era: by 2000 BCE there was contact between the civilisations of the Red Sea, the Gulf and the Indus Valley. South Asian merchants, Malay mariners and Buddhist monks, set a template for the Indian Ocean in the first centuries of the common era, as did the eventual emergence of empires like the Sasanians in Persia, the Guptas in India, and Funan in Southeast Asia.

South Asia has often been seen as a pivot of the Indian Ocean world, as it served as a stepping stone from east to west and the other way around. But connections across the ocean also involved the Middle East, East Asia and Africa. Islam should not be seen as the only factor which wove the ocean together from the seventh century; for the spread of Buddhist and Hindu doctrines to Southeast Asia occurred in the first five centuries of the common era. Trade and commerce were important to the making of the Indian Ocean world. Prior to the arrival of European empires, companies and private traders, there was a pattern of commerce across this sea which was under the control of sea-facing states, port cities and merchant diasporas. Trade was modulated by the seasons of the monsoon. Among the traded items were spices, precious stones and pearls, as well as rice and grain and indeed enslaved peoples.

Historians see the first European imperial enterprises as operating within this world, through partnerships with indigenous political elites, lenders and merchants. The Portuguese sought to reorganise trade through an insistence on the protection afforded by their licences and taxes. The Dutch, who were drawn to South Asia for cottons, indigo, saltpetre, silk, cinnamon and pepper, sought to follow in their tracks. Yet with the Dutch and the English came a new structure, the world-spanning joint-stock company. In India, this meant that Europeans established strategic settlements at ports. For the British the main bases became Madras, Bombay and Calcutta, around which their control of the Indian Ocean radiated. Even this quick sketch of the long histories of the Indian and Pacific Oceans points to the need to analyse the advent of the Europeans and the significant bridge between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which marked the powerful ascent of Europe in these oceans.

It is the starting premise of this book that revolution and counter-revolutionary empire did not obliterate these long-term histories. But the juxtaposition of new and old quickened with the extent of contact and globalisation making it difficult at times to differentiate what already existed from what had newly arrived. And with that quickening, the way that people thought of themselves, their territories and the globe itself was shifting. This was another characteristic feature of this age of revolutions and of the rise of empire.

The impact of the times as a phase of globalisation is evident in how indigenous peoples saw their seas, their histories and their place on the globe. Two treasures bear this out.

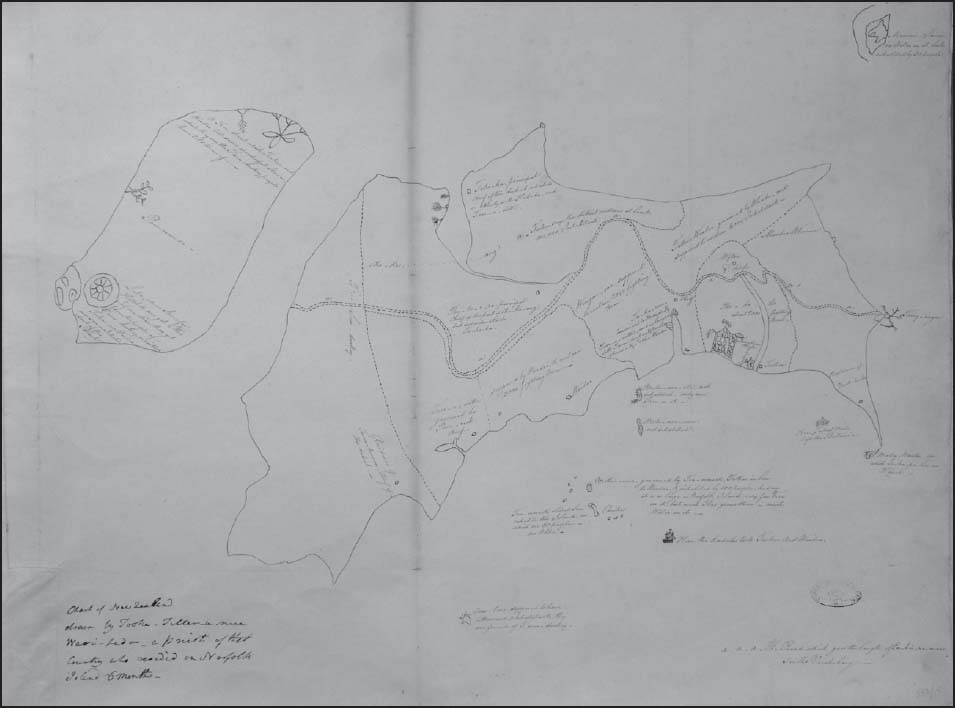

The First Fleet, the first detachment of convicts, arrived to found a colony at New South Wales in 1788, the year before the French Revolution. In 1793, two kidnapped Māori were brought to Norfolk Island off the coast of Australia, in order to teach convicts how to work the flax that grew on many of the island’s coastal cliffs. These two kidnapped men are now commonly called Tuki and Huru. They came to Norfolk Island on the Shah Hormuzear, which was crewed by lascars, and which had arrived at Port Jackson [now in Sydney] from Calcutta.[16] On their way to Norfolk Island they travelled in the company of 2,200 gallons of wine and spirits, six Bengal ewes and two rams. They were the first Māori to live in a European community, and the kidnapped Tuki, a priest’s son, and Huru, a young chief, became close to the commandant of the convict settlement, Philip Gidley King. King was unable to discern much about flax-working from the pair, given that it was women who worked the flax in their communities. Yet he got Tuki to a draw a map.

One commentator noted the extent of Tuki’s interests: ‘Too-gee [Tuki] was not only very inquisitive respecting England & c. (the situation of which, as well as that of New Zealand, Norfolk Island and Port Jackson, he well knew how to find by means of a coloured general chart).’ If Tuki’s use of the coloured general chart indicated his adoption of European cartography and his interest in locating his home in relation to neighbouring territories, he was also ‘very communicative respecting his own country … Perceiving he was not thoroughly understood, he delineated a sketch of New Zealand with chalk on the floor.’[17]

Tuki’s map of his ‘country’ is extraordinary not only because it is thought to be the oldest map drawn by a Māori. It shows ‘Ea-hei-no-maue’ and ‘Poo-name-moo’ which should be read as He Ahi Nō Maui or Mauis’s fire, the North Island; and Te Wai Pounamu or Greenstone Water, the South Island.[18] It combined a rich variety of elements: a double-dotted line across the North Island shows the road taken by the spirits of the dead or wairua and the place for leaping off into the underworld. On the map, this road ends with the representation of a sacred pōhutukawa tree. Within this map, and in the conversations that happened around its making, Tuki attended to population, harbours, the concentration of fighting men and the availability of water. All this demonstrates that there was an intermixing of Māori topography with European cartographic interest, which was driven for instance by the need to discover stopping places for their ships.[19] Tuki’s map sits within a larger set of Māori maps made for interpreters, surveyors, explorers and whalers among others. On their return to New Zealand, Tuki and Huru became important intermediaries between Māori and the British.[20]

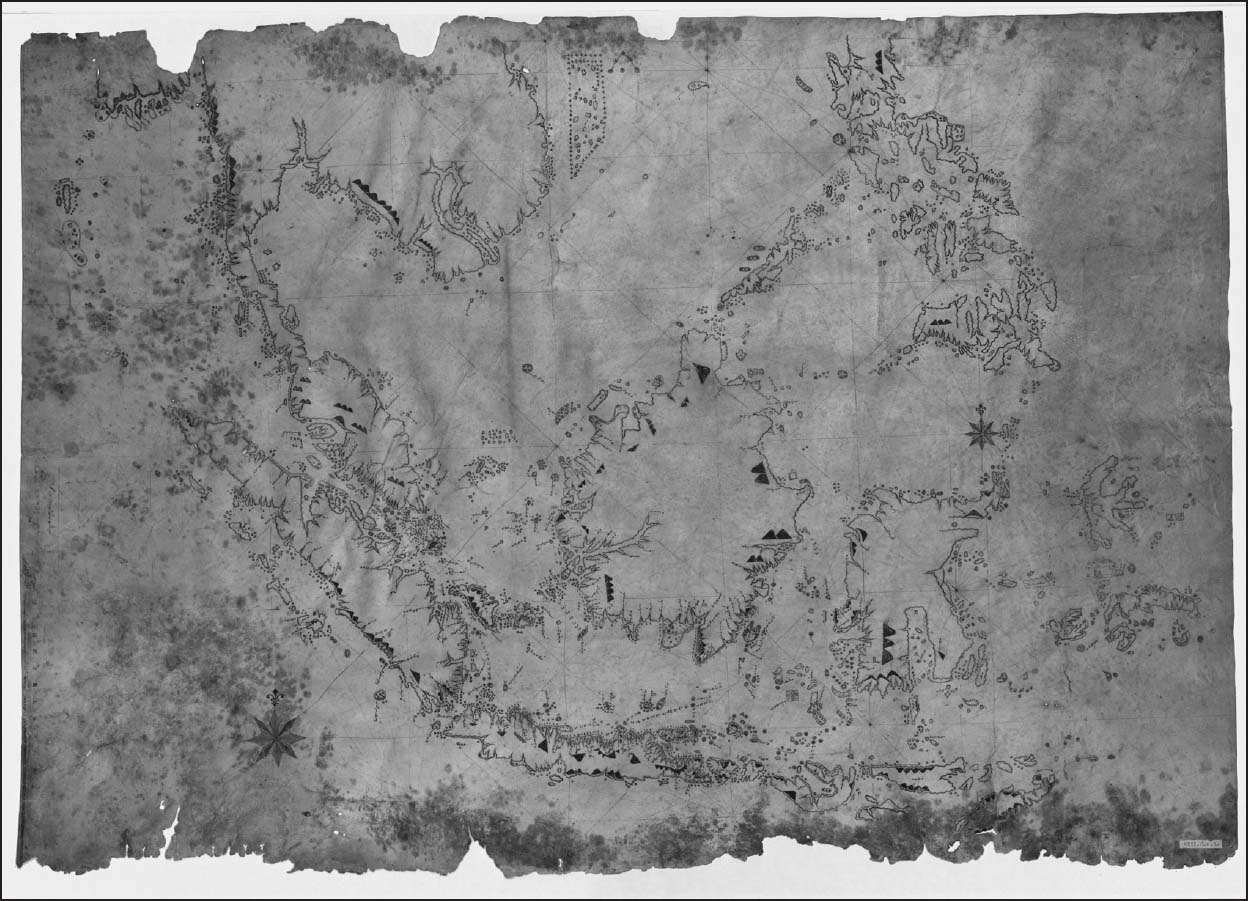

If Tuki’s map may stand here at the start of Waves Across the South for the Pacific, from the Indian Ocean comes a second intriguing map, once more showing how people were responding to this age of dramatic change by attempting to find and place themselves in a world in flux. This is a Bugis map, inscribed with Muslim era date AH 1231 (1816), shortly after the end of the Napoleonic wars, and it is worth noting here that British Singapore was established in 1819. The home of the Bugis is Celebes in south Sulawesi in today’s Indonesia and their wide circuit of sailing included northern Australia, where their vessels were known to Aboriginal Australians who traded with them. They converted to Islam from the seventeenth century.

Fig. 0.5 ‘Tuki’s map’

0.5 © The National Archives, ref. MPG1/532 (5)

The tattered and browned cowhide Bugis map, with coasts and islands in green and red ink, is one of a very rare set.[21] It has place names in Bugis script and records sea depths. It marks Dutch places of colonisation with flags, including Manila, which in fact was not Dutch but Spanish. It even shows a small section of the coast of Australia, and the Andaman and Nicobar islands. Once again, like Tuki’s map, this chart can’t be read purely as an indigenous artefact because it shows clear evidence of the impact of European traditions. (One possible theory is that it was heavily influenced by a map of the region drawn by a French captain, Jean-Baptiste d’Après de Mannevillette.[22]) The map includes the sign of a compass, now an object which plays a critical role in Bugis navigation today. The compass was already in use by Bugis by the eighteenth century.[23]

Fig. 0.6 Bugis nautical map, 1816

0.6 © Bugis nautical map on cowhide, AH 1231, c.1816, Kaart: VIII.C.a.2, Special Collections, Utrecht University Library.

Despite pointing to the adoption of European techniques, this map is consistent with established Bugis skills of navigation. Bugis navigators had to contend with the intersecting terrain of many islands and seas in Southeast Asia, a different challenge to that faced by Pacific islanders, including Māori, who navigated the open Pacific.[24] Noteworthy then is how the maritime fringe is presented in heavy and exaggerated detail, and islands and creeks are closely studied. This contrasts with the interiors of the land, where mountains alone are placed on the map, as they would have been seen from the sea.[25] These mountains probably helped with navigation.

The Bugis controlled Riau in the eighteenth century and made it a centre of trade between Europe, the Chinese and the Malay archipelago. Eventually, in 1784, the Riau Sultanate was taken over by the Dutch, like Makassar, another Bugis stronghold, which had fallen to the Dutch in 1667. This led to Bugis spreading across the region, roving the seas as traders, where they would be categorised as pirates by the British into the nineteenth century. They fought against the British in the fall of the Yogyakarta in Java in 1812.[26] However, the British relied on Bugis to connect up the early port of Singapore to regions further east as intermediaries, and the arrival of the Bugis fleet in Singapore, consisting of several thousand men, was a notable event in the port’s calendar.[27]

As these two objects demonstrate, Europeans did not have a monopoly over mapping, a form of knowledge which is often cast as the centrepiece of European imperial expansion. These maritime maps demonstrate the creativity and confidence of indigenous perspectives in the age of revolutions. While these Māori and Bugis maps cannot be read for pure indigenous traditions, they provide evidence of exchange and tension with European knowledge, at a time of dramatic flux.[28] Fittingly then, in another Bugis map a European steamboat appears in the lower left corner; even one of the proudest tokens of progress in the era, the steamboat, could be placed within Bugis sensibility.[29] Across the waves of the south, it is these unexpected features of indigenous politics, knowledge and practice that this book hopes to establish. Despite the powers of mechanised steamboats, indigenous and non-European peoples could find their paths in these waves of the southern hemisphere.

1

Travels in the Oceanic South

‘I will stick you on the Forecastle and set the Otaheiti men to shoot you.’[1] This was one of Peter Dillon’s favourite expressions. He captained the 400-ton St Patrick as it sailed from Valparaiso in Chile, in October 1825, to Calcutta (now Kolkata), the bustling hub of the new British empire. Dillon had a penchant for storytelling. He was full of detail about the grand European voyages across the Pacific in the centuries that had just passed.[2] Dillon named one of his sons after Napoleon, whom he venerated: the son was nicknamed Nap. Seen from this perspective, perhaps his threat to use Tahitian men against his white crew was Napoleonic. The aim was to stem the possibility of mutiny.

Dillon was an erratic maritime adventurer and private trader with aspirations of greatness, an Irishman born in French Martinique in 1788. If he is to be believed, he had served in the Royal Navy at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.[3] He then sailed for the Pacific. He was known to foster close relationships with South Pacific islanders, an attachment which began when he was resident in Fiji in 1808–9, when he made ‘considerable progress in learning their language’.[4] Pacific islanders called him ‘Pita.’[5] From 1809, he set himself up in Sydney, using it as a base for his private trade across the Pacific. He moved to Calcutta in 1816 and traded between Bengal and the Pacific. By this time, he had married. Mary Dillon accompanied him on his voyages from Calcutta.

In these journeys, Dillon linked many of the sites of the Waves Across the South together. This is why his life is a good starting point for our travels. His voyage of 1825–6 falls squarely in the middle of the age of revolutions and Dillon’s career is a telling gauge of changing times. For the British empire followed in the wake of people who may be placed next to Dillon, namely private traders, sailors, castaways, missionaries and so-called pirates. This new empire sought to reform their activities with more systematic colonisation, ‘free trade’ and liberal government.[6] In keeping with this shift to formal empire, Dillon spent the later phase of his life in Europe. He now combined a new set of interests, presenting plans for the settlement of the Pacific to the governments of France and Belgium and publishing a proposal for the colonisation of New Zealand by the British. In the 1840s, he was an active member of a characteristic association of reform in mid-nineteenth-century Britain, the Aborigines Protection Society, which was tied up with the humanitarian heritage of anti-slavery. He also set out a plan for sending Catholic missionaries to the Pacific.[7] He died in Paris in 1847.