Полная версия

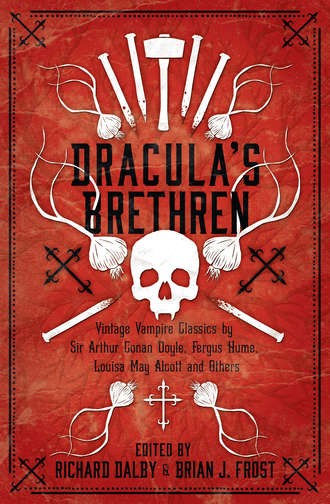

Dracula’s Brethren

The letter being sent off expressly by one of his retainers, the baron ordered some soldiers to attend with a bier, and taking Robert for their guide they went to fetch the body of Ruthven, and in the meantime he had a small tent erected for its reception, surmounted by a sable flag.

But this posthumous attention of the good baron was all in vain, for after a long absence, Robert and the soldiers returned, with the unwelcome news that the body of the gallant Scot was not to be found, but the spot where it had been deposited by the servants was still marked with the blood that had flowed from his gaping wounds and it was presumed that the enemy had found the corpse, and had conveyed it away to some obscure hole out of revenge for the slaughter he had dealt among their leaders before his fall. This event added materially to Ronald’s regret and sorrow, for the natives of the Isles of Escotia held a traditional superstition, that while the body lay unburied the spirit wandered denied of rest. He offered rewards for the body without success, and was at length obliged, though with much reluctance, to drop the affair.

The baron was obliged to pay his duty in England to his sovereign before he repaired to the Isles. Unexpected events detained him two months at the British court, but he at last effected his departure to his long wished-for home.

A courier made known his approach, and Lady Margaret, attended by the whole household, dressed in their best array, came forth to meet him, headed by the aged minstrel, and they received their lord with joyous shouts and lively strains, about half a mile from the gates of the castle.

Lord Ronald, as the carriage descended a steep hill that led into the valley, had a full view of the party approaching to meet him, and his heart felt elated at the compliment. He could discern his daughter; but how came it she was not in sables? Surely Ruthven, her betrothed lover, deserved that mark of respect to his memory! But he could observe that she was gaily dressed, and her high plume of feathers waving in the light breeze that adulated the air. The baron cast a look on his own deep mourning, and sighed; he was not pleased – but worse and worse. As he gained a nearer view, he perceived that his daughter was handed along, most familiarly by a knight. I had hoped, said he to himself, that Margaret would have rose superior to the inconstancy and caprice attributed to her sex. Can it be possible, that she has so soon forgot the valiant, accomplished Ruthven! Oh, woman! woman! are ye all alike? As the vehicle entered the valley, Ronald quitted it, to receive the welcome of his child and retainers.

Powers of astonishment! Was it, or was it not, illusion? By what miracle did he behold Ruthven, Earl of Marsden, standing before him, and Lady Margaret hanging with chaste expressions of delight on his arm; there was a scar on his forehead, and he was much paler than before the battle, but no other alteration was visible. As for Robert, he stood aghast, his hair bristled up and his joints trembled, and altogether would have served as a good model of horror to a painter or statuary.

Ruthven stretched forth his hand – ‘You seem astonished, my good lord,’ said he, ‘to find me here before you, or, indeed to find me here at all. I was discovered by some peasants returning from their daily labour, nearly covered with fern and leaves [‘Yes,’ said Robert, ‘that was Gilbert’s work and mine.’] by means of a little dog, who had scented out my body from its purposed concealment. They were very poor, and my clothes and decorations were a strong temptation, to which they yielded, they agreed to strip me, sell the clothes, and divide the spoil. While they were thus occupied, they perceived signs of life, and their humanity prevailed over every other consideration, I was conveyed to one of their cottages, and well attended. The man had a wonderful skill in herbs and simples, therefore my cure was rapid, but previous to my leaving them, I well rewarded everyone who had been instrumental in my preservation and freely forgave the intended plunder they had confessed to me, as it was the means directed by fate to prolong my existence, and restore me to my angelic Margaret.

‘When I recovered, I found the British forces had quitted Flanders, but I could not learn which direction my friend the baron (you my dear lord) had taken; so I hastened to Scotland with all the speed my situation would admit of, and we were retarded at sea by adverse winds. I found my dear betrothed, and her fair damsels, in deep mourning for my supposed loss; but I soon changed her tears for smiles, and her sables for gayer vestments: but at first her surprise, like yours, Lord Ronald, was too great to admit of utterance, but in time we became composed and grateful, and we agreed not to inform you of my existence, but astonish you on your arrival.’

The baron greeted his young friend most warmly and testified his hope that no more ill-omened events would disappoint the nuptials of the brave earl and Margaret, whom he tenderly clasped to his bosom, and kissing each cheek, remarked that she was the living image of his dear departed wife. He then turned to the old harper, and bidding him strike up a lively strain, proceeded to the castle, where all was joy and festivity; again resounded the song, and again the damsels, with their swains showed off their best reels à la Caledonia.

In the old steward’s room a plenteous board was spread, for the upper servants and retainers of the hospitable Lord of the Isles, who ordered flowing bowls and well replenished horns to the health of Ruthven and Margaret.

Some of the party were remarking on the wonderful preservation of Marsden’s earl by the Flemish peasants, instead of plundering and leaving him to perish, as many would have done to an almost expiring enemy.

‘Almost expiring!’ said Robert, whose cheeks had not yet recovered their usual hue since the meeting in the valley with Ruthven.

‘Almost expiring!’ he repeated; ‘I am certain the body of the earl was dead – aye, as dead as my great grandsire – when I and Gilbert carried him from the field of battle; and when we left him under the fern he was as cold as ice, and the blood from his wounds coagulated – No, no, he never came to life again; this Ruthven you have here must be a vampire.’

‘A vampire! a vampire!’ resounded from all the company, with loud shouts of laughter at poor Robert’s simplicity. ‘Perhaps you are a vampire,’ said his sweetheart, Effie, joining in the mirth, ‘so I shall take care how I trust myself in your power.’

Robert did not reply, and all the rest of the night he had to stand the bantering jests of his companions.

But Robert was right; Marsden’s earl died on the field of battle, and the moment the servants quitted the corpse, the vampire, wicked Montcalm, whose relics lay mouldering beneath a stone in Fingal’s cave, watching the moment, took possession, and reanimated the body; the wounds instantly healed, but the face wore a pallid hue, the invariable case with the vampires, their blood not flowing in that free circulation which belongs to real mortals.

The story told by the vampire was a fabrication, respecting the peasants, to impose on Lord Ronald and the Lady Margaret as to the appearance of the supposed Ruthven, and he well succeeded.

On previously consulting the Spirit of the Storm, the vampire had discovered that Margaret would be courted by Ruthven, Earl of Marsden; he also discovered, in his peep into futurity, that the young hero would be slain in battle, and this seemed to him a glorious opportunity to obtain possession of the lovely Margaret, and make her his victim, renovate his vampireship, and go on in the most diabolical career, hurling destruction on the human race, and drawing them into crime after crime, till they sank into the gulf of eternal infamy.

It now wanted a month to All-Hallow E’en and it so chanced, that in that year the next coming moon would set on that very eve from its full orbit. The vampire repaired to the cave of Fingal, and by magic means, which he well knew how to put in execution, he raised up some infernal spirits, whom he asked for orders. They told him they would consult their ruler Beelzebub, and he was to come on the third eve from thence for an answer.

This, then, was the decree – he must wed a virgin, destroy her, and drink her blood, before the setting of the moon on All-Hallow E’en, or terminate into mere nonentity; and if the maid was unchaste, the charm was dissolved. If he succeeded he was to quit the form of Earl Marsden and get egress into some other corpse to give it animation.

The supposed death of Ruthven had caused Margaret to imbibe the idea that the two figures she had seen in Fingal’s cave, and Ariel’s couplet prophetic but of one marriage, now made out by his fall, he being only a betrothed lover, and the stranger knight she regarded as her future spouse; but the return of the Earl again puzzled her, and she knew not what to think, but at length resolved on another visit to the mystic cavern. Possibly ashamed of confessing this weakness to her maidens, or, what is more probable, conscious that from the terrors they had experienced in attending her there, she could not persuade them to go a second time, she went alone, and soon after midnight, when all the castle was hushed in sound repose, save the vampire, who beheld from the lofty casement, the temporary flight of the enterprising Margaret. How did he thirst for her blood – how willingly would he have immolated the lovely maid that moment, and paid the infernal tribute, but for one clause that interposed and saved her from his fangs. This was the necessity of his being first legally married, in all due form, to the intended victim. He regarded her with a diabolical and malicious scowl, while, by as bright a starlight night as ever illumined the heavens, he saw her tripping through the park’s wide avenues of stately firs. He wondered where she was going, and felt apprehensive that some event was in agitation that might deprive him of his bride. The vampire had just concluded to follow her, when a heaviness he could neither resist or shake off, overpowered him and sealed his eyes in a deep sleep.

Margaret, in much perturbation and a beating heart, gained the way to the cave; but the interior was so dark that she was obliged to grope on her hands and knees to the magic well, and cast in the accustomed charm. The thunder rolled, and the storm commenced, but with not one quarter of the violence as on her preceding visit. The music followed in an harmonious strain, and the spirits of the storm and air soon stood before her. The beauty, the innocence, of the noble maid, her virtues and her benevolence, had interested these mystical beings in her behalf – yes, even the stern and oft obdurate Una felt for Margaret, and wished to save her. They could not alter the decree of fate, nor had they power over the vampires; the only thing that remained was to warn the enquirer, if possible, of her danger. For this purpose, they unfolded the curtain, and presented to her view, the real Ruthven on the field of battle, bleeding and a corpse. She heard his last sigh, saw his last convulsive motion – a grisly fleshless skeleton stood by his side, and at that moment entered his corpse, which sprung up reanimated! Margaret knew well the traditional tales of the vampires, and shuddered as she beheld one before her; for what could be more plain? No further vision was shown her – she was warned from the cave, and the fair one returned to the castle, dejected and spiritless. What did this mean? Ruthven, her adored Ruthven, could be no vampire – impossible – so accomplished, so clever, superior in most things to others of his rank. She passed the intervening hours in a very restless state, till they met at their morning repast in the small saloon. The vampire handed her to a chair; she remembered the scene in the cave, and shrank back with a feeling of disgust; but this was not lasting; the labours of the spirit of the storm and the air had not their intended effect; like advice given to young maidens that accords not with the inclination, it sank before the fascination of the object beloved, and she regarded what had been shown her as wayward spite in Una and Ariel; so ready are we to twist circumstances to act in conformity with our own inclination.

The dews of night, the chilling breeze, the damp of the magic cave of Fingal, joined to the fatigue and agitation of the noble maiden, caused a fever which confined her to her chamber several days, and again delayed the marriage. The vampire grew impatient, and before the Lady Margaret was scarce convalescent, he began to press for the nuptial ceremony, with what the good baron thought indecorous haste, though he made all possible allowance for repeated disappointments and youthful passions.

Robert, much better read than the warrior, his master, in the traditional tales of his country, and its popular superstitions, had not yet got the better of his shock at the reappearance of Ruthven in his native valley, when he felt convinced that Marsden’s earl died of his wounds on the field of battle at Flanders. ‘Aye, by the holy rood, he did,’ would the youth often mutter to himself. ‘May I never live to be married to my gentle Effie, and it wants but three days and three nights to that happy morn, if I did not see Ruthven’s eye-strings crack, and his heart’s veins burst assunder: this is a vampire, and this is the moon when those foul fiends pay their tribute, and now he is all impatience to wed my young mistress, forsooth – Yes, yes, ’tis plain enough: but what is the use of saying anything about it, my father and all the servants laugh at me; even my intended turns into ridicule, anything I advance on the subject, and calls me Robert, the vampire hunter: but I will not be deterred from doing my duty like an honest servant, let them jeer as they will. I am resolved to tell the baron all that I know, that is, all I think of his guest, and then he may please himself, and come what will, my conscience will be clear.’

Robert had courage to face a cannon, and never turned his back on the bravest foe, but he felt daunted at the disclosure he meant to make to Lord Ronald; the subject was awkward, and the vampire (if vampire he was) might take a summary revenge on him for his interference. Yet his resolution was not shaken, and seeking the cellar-man he procured a glass of cordial and a horn of ale to revive his spirits, and then, finding himself what he called his own man again, he sought the baron, whom he happened to find alone and taking his evening walk in the grounds, while Margaret and her lover were sitting at their music.

Robert told his tale with much hesitation and faltering, but the baron heard him with more patience than he expected, and made him recount every particular of his suspicions. ‘’Tis strange! ’tis marvellous strange!’ replied the good Lord Ronald; ‘for I have seen many persons from Flanders, and yet they never heard of the Earl of Marsden being saved by the peasants: one would have thought such news would have spread like wildfire.’

‘Neither does he go to mass or prayer,’ observed Robert, ‘as a Christian warrior ought to do; nor does he take salt on his trencher.fn1 And All-Hallow E’en is fast approaching,’ continued Robert: ‘this is the fatal moon, and my young mistress—’

‘Shall never be his,’ exclaimed the baron, ‘’till the moon sets, and the night, so tragic and pregnant of evil to many a spotless maid, is gone by; then if Ruthven is Marsden’s true earl, he may have my Margaret. She shall then be his, and I will turn all my fish ponds into bowls for whisky punch, and the great fountain in the forecourt shall flow with ale till not a Scot around can stand upon his legs, or he is no well-wisher to me or mine; but if he is an infernal vampire, his reign will be over. Faith, by St Andrew, I know not what to think, but I have had fearful dreams, portentous of evil to my ancient house.’

The baron dismissed Robert with a present, and many encomiums on his fidelity and zeal for him and the Lady Margaret. ‘My father,’ said the honest fellow, ‘has lived with you from youth to age: I was born within these walls, and my deceased mother suckled your amiable heiress; treachery in me would be double guilt: no, I would die to serve the house of Ronald!’

When the baron entered his daughter’s apartment, a group met his eyes, very ill calculated to give him pleasure in his present frame of mind full of supernatural ideas, and teeming with dread suspicions; Margaret had changed her robes of plaid silk for virgin white, her neck chain, bracelets and other ornaments of filigree silver, most exquisitely wrought. Ruthven was also dressed with elegance. The fair one’s attendants were also in their best. The steward and the physician of the household were present, and the chaplain stood with the sacred book in his hand.

‘We were waiting for you, my dear Lord Baron,’ said the vampire, Ruthven; ‘I have persuaded my lovely betrothed to be mine this very evening. We have been so very unfortunate, that I dread further delay, and think every hour teeming with evil till she is mine irrevocably.’

‘You have no rival,’ answered the baron, much alarmed and piqued: ‘you are secure in Margaret’s love and my consent. My friends and tenants will ill brook such privacy; they have been accustomed to see the daughters of the Lord of the Isles wedded in public pomp and magnificence, and to share in the festive and abundant hospitalities. No, by the shades of my ancestors, I will have no such doings.’

Ruthven pleaded hard, but the baron heeded not his arguments or eloquence, for the more he seemed bent on espousing Margaret then, the old lord thought more on Robert’s report and his own suspicions. Margaret, infatuated by the spell that cast an illusion over her senses, seemed to forget her proper dignity and the delicate decorum of her sex, and joined in the solicitations of her lover. ‘My dear father,’ said the beauteous maiden, ‘Ruthven and myself are in unison with each other’s sentiments; we seek not in pomp and glare for happiness; we place our prospects of future bliss in elegant retirement and domestic pleasures. Allow us to be now united, I entreat you, and you can afterwards treat your neighbours, retainers, and servants, as plenteously as you like, but I shrink from the idea of a public marriage.’

Ruthven took the hand of his betrothed, which she presented to him with the most endearing smiles, while her eyes modestly bent down and her cheeks covered with roseate blushes, and never did Lady Margaret look so irresistibly captivating as at that moment.

The baron, while she was speaking, trembled with emotion – Not for a single hour, said he, mentally, would I defer their happiness on account of bridal pomp, if I thought all was right; but I will not risk the sacrificing of so much loveliness, and that my only child, the image of my lost Cassandra, to a vampire; but he did not like to disclose the suspicions he had imbibed, for if they were founded in error, how grossly ridiculous would he appear, and he resolved to delay the nuptials, and stay the test of the moon. He therefore said, ‘It is my pleasure to give a full month to splendid preparation, ’tis but a short delay, and let me have the satisfaction to have the nuptials as I would wish them to be, in honour of Marsden’s earl and Ronald’s daughter.’

The baron observed the lover give a start at the words ‘a full month’, and his eyes shot forth a most malicious glance. He still held Margaret’s hand. ‘Nonsense! my good friend,’ said he, ‘this is not fair, from one warrior to another – Chaplain, begin the ceremony.’

The enraged baron flung off his guard, snatched the book from the hands of the priest, and bade Margaret retire with her maidens to another room, accusing Ruthven of being a vampire.

This was strongly resented by the accused, and, indeed, every one took his part, and laughed at the suggestion. This raised the baron’s passion so high that he was declared by the physician to be insane, and they coercively conveyed him to his chamber, and barred him in, where he was on the point of becoming frantic indeed, from the thoughts of his injunctions, for he was more convinced than ever of Ruthven being a supernatural imposter, or he would never have acted so uncourteous to a knight in his own castle.

Robert having heard from his father, the old steward, of the interruption of the marriage through the baron’s mania, in thinking the Earl of Marsden a vampire, and his lord’s confinement in the western turret, observed that he supposed the nuptials then were all off. His parent answered no, that the young people were not forced to obey such whims; that Lady Margaret was retired for an hour to regain her composure, and the chaplain would then perform the ceremony. ‘And who is to be the bride’s father?’ said Robert. – ‘I am to have that honour,’ replied the steward. – ‘And much good may it do you,’ said the son: ‘but if I was you, I’d cater better for the noble Lady Margaret than to give her to an evil spirit.’ – ‘Go to, for an ungracious bird,’ exclaimed Alexander; ‘you are as mad as your master; poor Effie will have but a crazy husband at the best of it.’ – ‘Better a crazy one, than a bloodthirsty vampire, father,’ observed Robert, who quitted the room, vexed at the loud peal of laughter, which was now set up against him.

Robert went out into the park, but returned privately into the castle by a bypath and a private door, of which he had a key, having procured it some time before he went to the wars, for he was then a rakish youth, and loved to steal out to the village dance or festival, after he was supposed to retire to rest for the night; but now he was contracted to the languishing blue-eyed Effie he was reformed, and voluntarily relinquished all such stolen delights. The key was now regarded by him as a treasure. ‘It helped me,’ said he to himself, ‘to sow my wild oats; it shall now aid me to perform a more laudable purpose. Little did I think to see the good Baron of the Isles a captive in his own castle; and for what, but that he is in too much possession of his senses to sacrifice his lovely virgin daughter to a vampire, for such, by the holy rood, is this fine Earl of Marsden. Why his face is the image of death itself, and his eyes glare; yet my Lady Margaret forsooth! thinks him very handsome, now she is under the influence of the wicked spell; the real Ruthven looked not so when he came to woo the noble fair one; but he says ’tis through his wounds in battle: I think by St Cuthbert, he has had time enough to get his complexion again, and he eats and drinks voraciously, it makes me sick to see him as I stand in waiting, and no salt – faugh!’

This long soliloquy, brought the faithful youth to the door of the baron’s prison; he drew the bolts and entered; his lord was pacing the chamber with unmeasured strides, and beating his forehead, while heavy sighs burst from his aged bosom. He started and stood still on Robert’s entrance.

‘Friend or foe?’ said he. – ‘Friend,’ replied Robert, ‘and when I prove otherwise to my most noble master and commander, may I be seized by the foul fiend and made food for vulture.’

‘I am not mad,’ said the good old veteran, ‘but I think I may say, I am distracted with grief.’

‘You are no more mad than I, my lord; I do not join in that absurd tale; but hasten and arm yourself. The marriage is to take place almost immediately – let us hasten and prevent it, ere it is too late.’

Lord Ronald was doubly shocked – his suspicions of the vampire were increased by this obstinate persisting in the nuptials against his command, and the want of tenderness and filial love testified by his daughter. How changed was Margaret! Did she choose for her bridal hours those of confinement to her sire – had she not supposed him insane, it is not to be thought she would have suffered him to be thus treated; this then was her season for connubial joys – the sudden insanity of her only surviving parent, he who had so ardently strove not only to fulfil his own duties, but to supply the place as far as possible of the late Lady Cassandra, his amiable wife, and he felt there was no sting so keen as a child’s ingratitude. The barbed arrow seemed to touch his very vitals, and for the first time in his life the brave Ronald shed tears.