Полная версия

Dracula’s Brethren

Stories about vampires of the non-human kind were also popular during the final decade of the nineteenth century. For instance, in H. G. Wells’ ‘The Flowering of the Strange Orchid’ (1894), a collector of exotic plants is attacked by a bloodsucking orchid growing in his hothouse; while in Fred M. White’s ‘The Purple Terror’ (1899) a group of explorers are menaced by vampire-vines in the Cuban jungle. Even more loathsome is the vampire-like monstrosity in Erckmann-Chatrian’s ‘The Crab Spider’ (1893), in which animals and people who enter a cave at a German health resort are attacked and have their bodies drained of blood by a giant arachnid. In another fascinating story, Sidney Bertram’s ‘With the Vampires’ (1899), explorers journeying up the Amazon encounter cave-dwelling vampire bats. The same geographical location is also the setting for Phil Robinson’s ‘The Last of the Vampires’ (1893), in which a German trader comes across a huge vampire-pterodactyl, to which human sacrifices are made.

A psychic detective whose cases sometimes involved vampire-like phenomena is Flaxman Low, who appeared in a series of allegedly real ghost stories in Pearson’s Magazine between 1898 and 1899 under the byline of E. & H. Heron, a pseudonym used by the mother-and-son writing team Kate and Hesketh Prichard. In ‘The Story of Baelbrow,’ for instance, Low investigates mysterious deaths at a reputedly haunted house, and discovers that a previously ineffectual spirit-vampire has become a deadly killer by activating an Egyptian mummy in his client’s private museum. In another exploit, ‘The Story of the Moor Road,’ a malevolent elemental becomes palpable after absorbing an invalid’s vitality; and, in ‘The Story of the Grey House,’ guests staying at a secluded country house are strangled and drained of blood by a demoniacal creeper growing in the shrubbery.

The 1890s was also a productive decade for vampire novels, but apart from a select few most are forgotten today. Towering above them all is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which, since its launch in 1897, has gone on to sell millions of copies around the world and is undoubtedly the most influential vampire novel ever written. Surviving changes in fashion and numerous indignities at the hands of clumsy editors, it has, over time, earned itself a unique place in the vampire canon, and has deservedly achieved the status of a classic of English literature. The enduring appeal of this novel is primarily due to its sensational plot and Stoker’s spellbinding narrative power, but it is also noteworthy for two other reasons. Firstly, it has systemised the rules of literary and cinematic vampirology for all time, and secondly we have in Count Dracula the definitive incarnation of the human bloodsucker.

The only novel from the 1890s to rival Stoker’s magnum opus in popularity is H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), which was the first novel to feature alien vampires. For the benefit of those who haven’t read Wells’ classic, or are only familiar with the plot through watching adulterated film versions, the vampires are the invading Martians, who, we learn, turned to vampirism after their digestive tracts atrophied almost completely, making them solely reliant on blood for sustenance. Initially they preyed on their fellow Martians, but when supplies of the life-giving fluid became exhausted they were forced to look beyond their own planet for survival, and found just what they needed on neighbouring Earth.

J. Maclaren Cobban’s Master of His Fate (1890), which was strongly influenced by Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, concerns the tragic fate of a scientist who has discovered a formula that enables him to renew his youth by absorbing energy from other people merely by touching them. However, as the necessity to absorb larger amounts of energy arises, he is forced to commit suicide to prevent the deaths of his ‘donors,’ who include the woman he loves. Another novel probably inspired by Stevenson’s split-personality classic is Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). While not usually thought of as a vampire, Gray can quite legitimately be likened to one in view of his destructive, self-indulgent lifestyle, an essential part of which is the consumption of other people’s life-energy in order to gain eternal youth. Vampirism of a similar nature is practised in H. J. Chaytor’s The Light of the Eye (1897) and L. T. Meade’s The Desire of Men: An Impossibility (1899). In the former, a man’s eyes have the power to suck out people’s vitality, while Meade’s thriller revolves around weird experiments in a strange house, where the aged regain their lost youth at the expense of the young. Other novels from the 1890s with vampirism as the main or subsidiary theme are: The Soul of Countess Adrian (1891), by Mrs Campbell Praed; The Strange Story of Dr Senex (1891), by E. E. Baldwin; Sardia: A Story of Love (1891), by Cora Linn Daniels; The Fair Abigail (1894), by Paul Heyse; The Lost Stradivarius (1895), by J. Meade Falkner; Lilith (1895), by George MacDonald; The Blood of the Vampire (1897), by Florence Marryat; In Quest of Life (1898), by Thaddeus W. Williams; and The Enchanter (1899), by U. L. Silberrad.

The only vampire novels from the first decade of the twentieth century of any significance are In the Dwellings of the Wilderness (1904), by C. Bryson Taylor; The Woman in Black (1906), by M. Y. Halidom; and The House of the Vampire (1907), by George Sylvester Viereck. In the first of these, a party of American archaeologists is attacked vampirically by the revivified mummy of an Egyptian princess; while the novel by the pseudonymous M. Y. Halidom features a glamorous seductress who has retained her beauty and youthful appearance for centuries by sucking the blood of her lovers. In contrast, the vampire in Viereck’s novel – an arrogant, self-centred writer – acts like a psychic sponge, stealing the most creative thoughts of his protégés and passing them off as his own.

A short story from the turn of the century which has remained popular over the years is F. G. Loring’s ‘The Tomb of Sarah.’ First published in the December 1900 issue of Pall Mall Magazine, it centres on the nocturnal activities of an undead witch who has been accidentally released from the confinement of her tomb during renovations to a church. For a while her nightly forays in search of blood cause great concern among the local community, but she is eventually caught and permanently laid to rest by the time-honoured ritual of driving a stake through her heart. A much more sensational story from this period, Richard Marsh’s ‘The Mask’ (Marvels and Mysteries, 1900), is about a homicidal madwoman adept in the art of mask-making who transforms herself into a raving beauty and tries to suck the blood of the story’s hero. Female vampires are also featured in two stories in Hume Nisbet’s collection Stories Weird and Wonderful (1900). In ‘The Vampire Maid’ a weary traveller finds lodgings at an isolated cottage on the Westmorland moors, only to be preyed on during the night by the landlady’s vampire daughter; and in ‘The Old Portrait’ a woman depicted in a painting comes to life and tries to suck out the vitality of the picture’s owner with a long, lingering kiss. Offering more substantial fare, Phil Robinson’s ‘Medusa,’ a well-crafted story from Tales by Three Brothers (1902), is about a seductive femme fatale who feeds on the life force of her male admirers. A more subtle threat is posed in Mary E. Wilkins Freeman’s ‘Luella Miller’ (1902), the title character of which unconsciously absorbs the vitality of her nearest and dearest, causing them to languish while she blooms. On more traditional lines is F. Marion Crawford’s vampire classic ‘For the Blood is the Life’ (1905), in which a gypsy girl returns from the dead to vampirize the man who had spurned her love. In another first-rate story, R. Murray Gilchrist’s ‘The Lover’s Ordeal’ (1905), a young woman challenges her fiancé to pass through an ordeal before she will consent to marry him. This involves spending the night at a haunted house; but, unbeknown to the couple, a beautiful vampiress is lurking in one of the rooms, waiting patiently for her next victim to come along. An inconsequential piece, by comparison, is ‘The Vampire,’ by Hugh McCrae, which was originally published under the pseudonym ‘W. W. Lamble’ when it appeared in the November 1901 edition of The Bulletin.

One of the Edwardian era’s finest vampire stories is ‘Count Magnus,’ by M. R. James, which has been anthologised many times since its debut in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904). Among this author’s spookiest tales, it chronicles the events leading up to the gruesome death of an English scholar, who becomes a doomed man after delving too deeply into suppressed legends about a notorious seventeenth-century Swedish nobleman. A minor story, ‘The Vampire’ (1902), by Basil Tozer, has seemingly sunk into oblivion, a fate that may well have befallen Frank Norris’s ‘Grettir at Thorhall-stead’ (1903) had it not been rescued from obscurity by fantasy historian Sam Moskowitz, who reprinted it in his 1971 anthology Horrors Unknown. Not entirely original, Norris’s story is a retelling of an episode in Grettir’s Saga, in which the legendary Icelandic hero has a fateful encounter with a vampire. Coincidentally, the same episode also provided the inspiration for Sabine Baring-Gould’s ‘Glámr,’ which was included in his A Book of Ghosts (1904). Another vampire story from this collection is ‘A Dead Finger,’ in which the hapless protagonist is preyed on by the disembodied spirit of a dead man, which is gradually stealing his vitality in an attempt to create a new body for itself. On similar lines to this story are Luigi Capuana’s ‘A Vampire’ (1907), which describes how the disembodied spirit of a woman’s deceased husband attempts to suck the blood of her infant child; and Lionel Sparrow’s ‘The Vengeance of the Dead’ (1910), in which a thoroughly evil man has, since his demise, existed in a state of life-in-death by stealing vitality from the living and transferring it to his corpse. More ambitiously, the unscrupulous scientist in C. Langton Clarke’s ‘The Elixir of Life’ (1903) has isolated the vitic force and found a way to transfer it from others to himself, thereby attaining a kind of immortality. More conventional in their treatment of the vampire theme are ‘The Vampire Nemesis’ (1905), by ‘Dolly,’ and ‘The Singular Death of Morton’ (1910), by Algernon Blackwood. In the former story a suicide is reincarnated as a giant vampire bat; and, in the latter, two men holidaying in France encounter a sinister woman, who lures one of them to a cemetery and sucks all the blood from his body.

Some of the best stories from the Edwardian era feature vampires in unusual guises. In Morley Roberts’ ‘The Blood Fetish’ (1909), for example, a severed hand lives on as an independent entity by absorbing the blood of both animal and human victims. In another morbid tale, Horacio Quiroga’s ‘The Feather Pillow’ (1907), a young woman has all the blood gradually sucked out of her by a monstrous insect secreted inside the pillow on her bed; and in F. H. Power’s ‘The Electric Vampire’ (1910) a mad scientist creates a giant, electrically-charged insect which feeds on blood. Even more bizarre is Louise J. Strong’s ‘An Unscientific Story’ (1903), in which a professor who has succeeded in breeding the ‘life-germ’ in his laboratory soon realises the folly of his experiments when his creation grows at a fantastic rate and within a short time forms itself into a humanoid creature which exhibits a craving for blood.

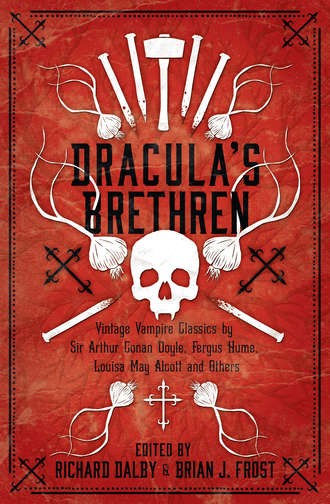

The first anthology to gather together a sizeable number of stories from this golden age of vampire fiction was Richard Dalby’s Dracula’s Brood (1987), which contained twenty-three rare stories written by friends and contemporaries of Bram Stoker. Then, after years of searching through dusty old books and defunct magazines, Richard and fellow vampire enthusiast Robert Eighteen-Bisang compiled an even rarer collection of stories for their 2011 anthology Vintage Vampire Stories. Now, after more diligent searching, Richard and I have put together this stunning new collection of stories, nearly all of which have been unavailable for many years, and include several forgotten gems whose resurrection from an undeserved obscurity should finally bring them the recognition they deserve.

BRIAN J. FROST

THE BRIDE OF THE ISLES

A Tale Founded on the Popular Legend of the Vampire

Anonymous

When this story, which is based on James Robinson Planché’s play The Vampire; or, The Bride of the Isles, received its first publication in 1820, the publisher, J. Charles of Dublin, took the liberty of falsely attributing it to Lord Byron, and the real author is unknown. Nevertheless, it is an excellent example of the bluebook or ‘Shilling Shocker,’ which were the terms usually used to describe short Gothic tales published in booklet form during the early 19th century. Retailing between sixpence and a shilling, they were about four by seven inches in size, and their closely printed pages were stitched into a cover made of flimsy blue paper. These luridly illustrated publications were especially popular with members of the lower classes, many of whom craved the thrill of reading stories revolving around shocking, mysterious and horrid incidents, but couldn’t afford to buy expensive Gothic novels, which were often published in three volumes. A copy of the rare 1820 first edition, complete with its coloured frontispiece, fetched £2000 at auction three years ago.

‘THOUGH the cheek be pale, and glared the eye, such is the wondrous art the hapless victim blind adores, and drops into their grasp like birds when gazed on by a basilisk.’

THERE IS A popular superstition still extant in the southern isles of Scotland, but not with the force as it was a century since, that the souls of persons, whose actions in the mortal state were so wickedly atrocious as to deny all possibility of happiness in that of the next; were doomed to everlasting perdition, but had the power given them by infernal spirits to be for a while the scourge of the living.

This was done by allowing the wicked spirit to enter the body of another person at the moment their own soul had winged its flight from earth; the corpse was thus reanimated – the same look, the same voice, the same expression of countenance, with physical powers to eat and drink, and partake of human enjoyments, but with the most wicked propensities, and in this state they were called vampires. This second existence as it may not improperly be termed, is held on a tenure of the most horrid and diabolical nature. Every All-Hallow E’en, he must wed a lovely virgin, and slay her, which done, he is to catch her warm blood and drink it, and from this draught he is renovated for another year, and free to take another shape, and pursue his Satanic course; but if he failed in procuring a wife at the appointed time, or had not opportunity to make the sacrifice before the moon set, the vampire was no more – he did not turn into a skeleton, but literally vanished into air and nothingness.

One of these demoniac sprites, Oscar Montcalm, of infamous notoriety in the Scotch annals of crime and murder (who was decapitated by the hands of the common executioner), was a most successful vampire, and many were the poor unfortunate maidens who had been sacrificed to support his supernatural career, roving from place to place, and every year changing his shape as opportunity presented itself, but always chosing to enter the corpse of some man of rank and power, as by that means his voracious appetite for luxury was gratified.

Oscar Montcalm had seen, and distantly adored in his mortal state, the superior beauty of the Lady Margaret, daughter of the Baron of the Isles, the good Lord Ronald; but, such was his situation, he had not dared to address her; however, he did not forget her in his vampire state, but marked her out for one of his victims, in revenge for the scorn with which he had been treated by her father.

Lady Margaret, though lovely and well proportioned, entered her twentieth year unmarried, nor had she ever been addressed by a suitor whom she could regard with the least partiality, and with much anxiety she sought to know whether she should ever enter into wedlock, and what sort of person her future lord would be. With credulity pardonable to the times in which she lived, and the narrow education then given to females, even of rank, she consulted Sage, Seer and Witch, as to this important event; but it is not to be wondered at that she met with many contradictions, everyone telling a different tale. At length urged on by the irresistible desire to pry into futurity, she repaired with her two maidens, Effie and Constance, to the Cave of Fingal, where, cutting off a lock of her hair, and joining it to a ring from her finger, she cast it into the well, according to the directions she had received from Merna, the Hag of the mountains, who had instructed the fair one as to this expedition.

No sooner was the ring flung into the well than a dreadful storm arose; the torches, which the attendant maidens had borne, were extinguished, and the immense cave was in utter darkness: loud and dreadful was the thunder, accompanied by a horrid confusion of sounds, which beggars description.

Margaret and her companions sunk on their knees; but they were too stupefied with horror to pray, or to endeavour to retrace their way out of this den of horrors. Of a sudden, the cave was brilliantly illuminated, but with no visible means of light, for there were neither torch, lamp, or candle. Solemn music was heard, slow and awfully grand, and in a few minutes two figures appeared, one heavy, morose in countenance, and clad in dark robes, who announced herself as Una, the spirit of the storm, and touching a sable curtain, discovered to the view of Margaret the figure of a noble young warrior, Ruthven, Earl of Marsden, who had accompanied her father to the wars. Again the storm resounded, the curtain closed, and the cave resumed its darkness; but this was only transient – the brilliant light returned – Una was gone, and the light figure, dressed in transparent robes, sprinkled over with spangles remained. With her wand she pulled aside the curtain, and a young man of interesting appearance was visible, but his person was a stranger to the fair one. Ariel, the spirit of the Air, then waved her hand to the entrance of the cave, as a signal for them to depart, and bowing low, they withdrew, amid strains of heart-thrilling harmony, rejoiced to find themselves once more in an open space, and they happily returned in safety to the baron’s castle. The Lady Margaret was well pleased with what she had seen, as promising her two husbands, though she was somewhat puzzled by calling to mind a couplet that Ariel had repeated three or four times, while the curtain remained undrawn.

‘But once fair maid, will you be wed,

You’ll know no second bridal bed.’

What could this mean? Surely she would never stoop to illicit desires or intrigue? She thought she knew her own heart too well.

The vampire had seen into the designs of Margaret to visit the Cave of Fingal, and he sought out Ariel and Una, to whom, by virtue of his supernatural rights, he had easy access. The spirit of the air would not befriend him, but the spirit of the storm assisted him to pry into futurity; and to suit his views, she presented the figure of Ruthven, Earl of Marsden. In the meantime, Marsden had the good fortune to save Lord Ronald’s life in the battle, and the wars being ended, or at least suspended for a time, he invited the gallant youth home with him to his castle, to pass a few months amid the social rites of hospitality and the pleasure of the chase.

The Lady Margaret received her father with dutiful affection, and gratitude to providence for his safe return, and she beheld young Marsden with secret delight; but when informed that he had preserved the baron from overpowering enemies, her gratitude knew no bounds, and she looked so beautiful and engaging, while returning her thankful effusions for the service he had rendered her father, that the earl could not resist the impulse, and from that hour became deeply enamoured of the lovely fair one.

Marsden’s rank and birth were unexceptionable but his fortune was very inadequate to support a title, which made him (added to the love of military glory) enter into the profession of arms, of which he was an ornament.

Margaret was the only child, and her father abounding in wealth and honours; it might therefore be presumed that an ambition might lead him to form very exalted views for the aggrandisement of his heiress; and so he had, but perceiving how high his preserver stood in the good graces of his darling child, and that the passion was becoming mutual, he resolved not to give any interruption to their happiness, but if Marsden could win Margaret to let him have her, as a rich reward for the service he had performed amid the clang of arms.

Parties were daily formed by the baron for the chase, hawking, or fishing, while the evening was given to the festive dance, or the minstrels tuned their harps in the great hall, and sang the deeds of Scottish chiefs, long since departed, amongst whom the heroic Wallace was not forgot.

The love of Ruthven and Lady Margaret were now generally known throughout the islands and congratulations poured in from every quarter.

A day was fixed for the nuptials, and magnificent preparations were made at the castle for the celebration of the ceremony, when the sudden and severe illness of the baron caused a delay. He wished them not to defer their marriage on his account; but the young people, in this instance would not obey him, declaring their joys would be incomplete without his revered presence.

The baron blessed them for this instance of love and filial duty, but he still felt a strong desire to have the marriage concluded.

The baron was scarce recovered, when he and Ruthven were summoned to the field of battle, a war having broken out in Flanders, and the marriage was deferred till their return; and taking a most affectionate leave of the Lady Margaret, the father and lover left the castle, and the fair one in the charge of old Alexander, the faithful steward, with many commands and cautions respecting the edifice and the lady, whom they both regarded as a gem of inestimable value, with whom they were loath to part, but imperious duty and the calls of honour allowed no alternative.

Robert, the old steward’s son, attended the baron abroad; and Marsden took his own servant the faithful Gilbert. They were successful in several skirmishes with the enemy, but in the final engagement Ruthven lost his life, dying in the arms of the Lord of the Isles, who mourned over him as for a beloved son, and he ordered Robert and Gilbert, who were on the spot, to convey the body to a place beyond the carnage, that when the battle was over he might see it (if he himself survived) and have the valued remains interred in a manner that became an earl and a soldier, dying in defending his country’s cause.

The battle ended, for the glory and success of Great Britain, and the good Baron of the Isles was unhurt, so was Robert, but Gilbert was amongst the slain.

Lord Ronald, fatigued with the sharp action of the day, in which he had borne his part with a vigour surprising to his time of life, for his head was now silvered over with the honourable badge of age, repaired to his tent to take some refreshment and an hour’s rest on his couch, to invigorate his frame. The couch eased his weary limbs, but his eyes closed not, and all his thoughts were on Ruthven, and the distress the sad news would give to his dear child. He arose, and with trembling fingers penned a letter to her, describing the melancholy event, and exhorting her, for the sake of her father, to support this trial with resignation and patience, and bow to the dispensations of Providence, who orders all things eventually for the best, however severe and distressing they seem at the time. He ended his letter by observing that he should return to the castle of the Isles without delay, being anxious to fold her in his arms, and that he should bring the corpse of the brave Marsden to his native land.