Полная версия

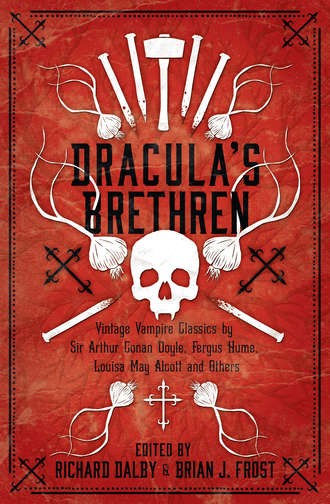

Dracula’s Brethren

At that moment the old cook’s assistant, a peasant woman, not yet past middle age, a terrible coquette, who always found something to pin to her cap – a bit of ribbon, a pink, or even a scrap of coloured paper, if she had nothing better – passed by, in a tightly girt apron, which displayed her round, sturdy figure.

‘Good day, Homa!’ she said, seeing the philosopher. ‘Aie, aie, aie! what’s the matter with you?’ she shrieked, clasping her hands.

‘Why, what is it, silly woman?’

‘Oh, my goodness! Why, you’ve gone quite grey!’

‘Aha! why, she’s right!’ Spirid pronounced, looking attentively at the philosopher. ‘Why, you have really gone as grey as our old Yavtuh.’

The philosopher, hearing this, ran headlong to the kitchen, where he had noticed on the wall a fly-blown triangular bit of looking-glass before which were stuck forget-me-nots, periwinkles and even wreaths of marigolds, testifying to its importance for the toilet of the finery-loving coquette. With horror he saw the truth of their words: half of his hair had in fact turned white.

Homa Brut hung his head and abandoned himself to reflection. ‘I will go to the master,’ he said at last. ‘I’ll tell him all about it and explain that I cannot go on reading. Let him send me back to Kiev straight away.’

With these thoughts in his mind he bent his steps towards the porch of the house.

The sotnik was sitting almost motionless in his parlour. The same hopeless grief which the philosopher had seen in his face before was still apparent. Only his cheeks were more sunken. It was evident that he had taken very little food, or perhaps had not eaten at all. The extraordinary pallor of his face gave it a look of stony immobility.

‘Good day!’ he pronounced on seeing Homa, who stood, cap in hand, at the door. ‘Well, how goes it with you? All satisfactory?’

‘It’s satisfactory, all right; such devilish doings, that one can but pick up one’s cap and take to one’s heels.’

‘How’s that?’

‘Why, your daughter, your honour … Looking at it reasonably, she is, to be sure, of noble birth, nobody is going to gainsay it; only, saving your presence, God rest her soul …’

‘What of my daughter?’

‘She had dealings with Satan. She gives one such horrors that there’s no reading scripture at all.’

‘Read away! read away! She did well to send for you; she took much care, poor darling, about her soul and tried to drive away all evil thoughts with prayers.’

‘That’s as you like to say, your honour; upon my soul, I cannot go on with it!’

‘Read away!’ the sotnik persisted in the same persuasive voice, ‘you have only one night left; you will do a Christian deed and I will reward you.’

‘But whatever rewards … Do as you please, your honour, but I will not read!’ Homa declared resolutely.

‘Listen, philosopher!’ said the sotnik, and his voice grew firm and menacing. ‘I don’t like these pranks. You can behave like that in your seminary; but with me it is different. When I flog, it’s not the same as your rector’s flogging. Do you know what good leather whips are like?’

‘I should think I do!’ said the philosopher, dropping his voice; ‘everybody knows what leather whips are like: in a large dose, it’s quite unendurable.’

‘Yes, but you don’t know yet how my lads can lay them on!’ said the sotnik, menacingly, rising to his feet, and his face assumed an imperious and ferocious expression that betrayed the unbridled violence of his character, only subdued for the time by sorrow.

‘Here they first give a sound flogging, then sprinkle with vodka, and begin over again. Go along, go along, finish your task! If you don’t – you’ll never get up again. If you do – a thousand gold pieces!’

‘Oho, ho! he’s a stiff one!’ thought the philosopher as he went out: ‘he’s not to be trifled with. Wait a bit, friend; I’ll cut and run, so that you and your hounds will never catch me.’

And Homa made up his mind to run away. He only waited for the hour after dinner when all the servants were accustomed to lie about in the hay in the barns and to give vent to such snores and wheezing that the backyard sounded like a factory.

The time came at last. Even Yavtuh closed his eyes as he lay stretched out in the sun. With fear and trembling, the philosopher stealthily made his way into the pleasure garden, from which he fancied he could more easily escape into the open country without being observed. As is usual with such gardens, it was dreadfully neglected and overgrown, and so made an extremely suitable setting for any secret enterprise. Except for one little path, trodden by the servants on their tasks, it was entirely hidden in a dense thicket of cherry-trees, elders and burdock, which thrust up their tall stems covered with clinging pinkish burs. A network of wild hop was flung over this medley of trees and bushes of varied hues, forming a roof over them, clinging to the fence and falling, mingled with wild bell-flowers, from it in coiling snakes. Beyond the fence, which formed the boundary of the garden, there came a perfect forest of rank grass and weeds, which looked as though no one cared to peep enviously into it, and as though any scythe would be broken to bits trying to mow down the stout stubbly stalks.

When the philosopher tried to get over the fence, his teeth chattered and his heart beat so violently that he was frightened at it. The skirts of his long coat seemed to stick to the ground as though someone had nailed them down. As he climbed over, he fancied he heard a voice shout in his ears with a deafening hiss: ‘Where are you off to?’ The philosopher dived into the long grass and fell to running, frequently stumbling over old roots and trampling upon moles. He saw that when he came out of the rank weeds he would have to cross a field, and that beyond it lay a dark thicket of blackthorn, in which he thought he would be safe. He expected after making his way through it to find the road leading straight to Kiev. He ran across the field at once and found himself in the thicket.

He crawled through the prickly bushes, paying a toll of rags from his coat on every thorn, and came out into a little hollow. A willow with spreading branches bent down almost to the earth. A little brook sparkled pure as silver. The first thing the philosopher did was to lie down and drink, for he was insufferably thirsty. ‘Good water!’ he said, wiping his lips; ‘I might rest here!’

‘No, we had better go straight ahead; they’ll be coming to look for you!’

These words rang out above his ears. He looked round – before him was standing Yavtuh. ‘Curse Yavtuh!’ the philosopher thought in his wrath; ‘I could take you and fling you … And I could batter in your ugly face and all of you with an oak post.’

‘You needn’t have gone such a long way round,’ Yavtuh went on, ‘you’d have done better to keep to the road I have come by, straight by the stable. And it’s a pity about your coat. It’s good cloth. What did you pay a yard for it? But we’ve walked far enough; it’s time to go home.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.