полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

The reader will observe that in this train the Master-General is not included, even in the contingency of the King's accompanying it himself. Lord Dartmouth had another duty to perform. He had been appointed Admiral of the Fleet which was to engage, if possible, the immense number of vessels which accompanied William to England. The winds fought against Dartmouth. First, he was kept at the mouth of the Thames by the same east winds that wafted the enemy to their landing-place at Torbay; and when, at last, able with a fair wind to follow down the Channel in pursuit, just as he reached Portsmouth, the wind changed: he had to run into that harbour, and his opportunity was lost – an opportunity, too, which might have reversed the whole story of the Revolution, for there was more loyalty to the King in the navy than in the army, – a loyalty which was whetted, as Macaulay well points out, by old grudges between the English and Dutch seamen; and there was in James's Admiral an ability and an integrity which cannot be doubted. Had the engagement taken place, and the King's fleet been successful, it does not require much experience of the world's history to say that the Revolution would have been postponed for years, if not for ever, for it is marvellous how loyal waverers become to the side which has the first success. Nor is this the first or only case on which a kingdom, or something equally valuable, has hung upon a change of wind. How history would have to be re-written had James Watt but lived two centuries earlier than he did!

The Lieutenant-General who was to command the train was Sir Henry Shore, who had been appointed an Assistant and Deputy at the Board to Sir Henry Tichborne. The latter was, doubtless, the Lieutenant-General, whose presence would also have been required had the King in person accompanied the train.

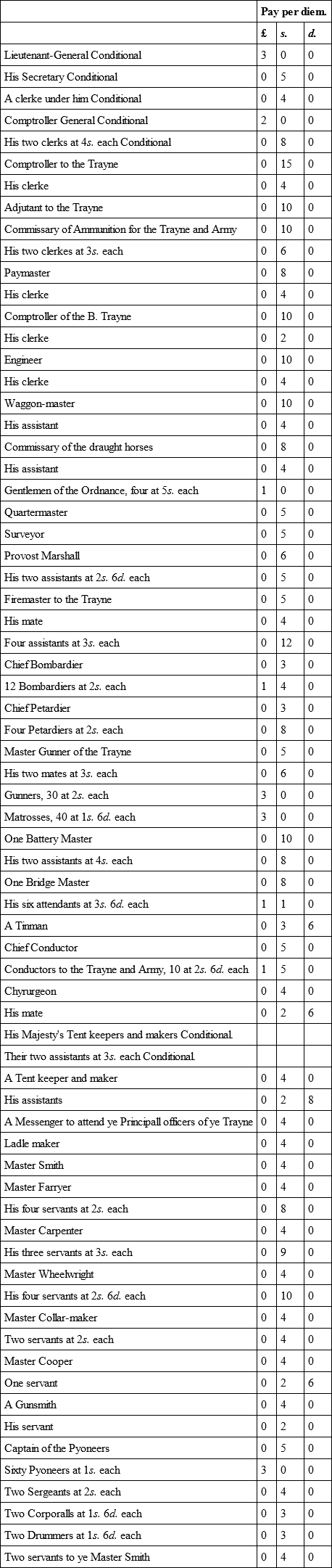

A List of the proper Persons, Ministers, and Attendants, of the Trayne of Artillery, viz. —

(Signed) Dartmouth.

The reader will observe that the position of the medical officers of a train was still a very degraded one, relatively speaking, in point of pay. The surgeon ranked with the ladle-maker, the chief artificers, and the messenger; while his assistant received the same remuneration for his services as did the servants of the master wheelwright and master cooper. The presence, in this train, of an Adjutant and a Battery Master, is worthy of note, and also the intimation that then, as now, on service, the Artillery had to take their share in the transport of the small-arm ammunition of the Army.

History moved rapidly now. After James's flight and a brief interregnum, the Ordnance Office moves on again with spirit under the new Master-General, the Duke de Schomberg. Judging from the vigorous conduct displayed by him during his brief career at the Board, one cannot but regret that it was so soon cut short. One little anecdote reveals the energy of the man's character, and enlists the sympathy of that part of posterity – and the name is Legion! – which has suffered from red tape and routine. There was naturally a strong feeling in Scotland against the new King. Presbyterianism itself could not dull the beating of the national heart, which was moved by the memories of the old line of Monarchs which had been given to England, whose gracious ways almost condoned their offences, and whose offences were easily forgotten in this their hour of tribulation.

Men, guns, ammunition, and transport were all required for Edinburgh and Berwick; but between the demand and the supply stood that national buffer which seems to be England's old man of the sea – a public department. For transport the Master-General had to consult the Admiralty, who, being consulted, began to coil the red tape round the Master's neck, and nothing more. He entreats, implores, and prays for even one ship to carry special engineers and messages to the Forth; but the Admiralty quietly pigeon-holes his prayers in a style worthy of two centuries later. The Duke will have none of it: he writes to the Board to give up this useless correspondence with a wooden-headed Department; to take his own private yacht, and carry out the King's service, without delay. Would that, to every wearied postulant, there were a private yacht to waft him out of the stagnant pool which officialism considers the perfection of Departmental Management, and in which he might drift away from the very memory of pigeon-holes and precedents!

As might be expected, volumes of warrants, at this time, reveal the changes made among the officials of the Ordnance. The preparing of a warrant implied a fee; it is not to be wondered at, therefore, that they were many. No office under the Ordnance was too low to escape the necessity of a warrant. There were chimney-sweeps to the Ordnance who have been made immortal by this necessity, paviours, druggists, messengers, and labourers. All must be made public characters, because all must pay. Sex is no protection. Candidates for Ordnance appointments who belong to the fair sex cannot plead shyness and modesty in bar of their warrants. So that Mary Pickering, who was reappointed cooper at the Fort of Upnor, near Chatham, and Mary Braybrooke, appointed turner at the same time, have come down to posterity for the fee of ten shillings, when fairer and nobler maidens have been forgotten.

There are many Dutch, German, and even French names among the new officials appointed for the Board's service. But reappointments are, by no means, rare, if the old incumbents would but change their allegiance. Among the changes introduced by the Duke de Schomberg was one by which not merely were there gentlemen of the Ordnance for the Tower and the various trains, but also "for the out parts: " and if there were no heavier duties for them to perform than those specified in their warrants, they must have had a very easy time of it, and earned their forty pounds a year without much labour. According to their warrants, their duty was to see that "all ye aprons, beds, and coynes belonging to their Majesties' Traynes of Artillery at ye outposts do remain upon the guns and carriages." If this were really all they had to do, the old gunners of garrisons might have done it quite as well for half the money.

The difficulty of getting arms for the troops which were being raised for service in Ireland alarmed the Board greatly. Very strong measures had to be taken: penalties were threatened on every one who kept arms concealed, or failed to bring them to the Board; and a house-to-house search was authorized. Gunsmiths were forbidden to sell to private individuals, and commanded to devote all their energies to manufacturing arms for the Board, and yet the need was sore. Horses, also, had to be bought, and could with difficulty be obtained; and such as were procured could not bear the test of examination. So bad were they, that at last the Master-General inspected in person not merely the horses bought for the Artillery, but also the persons who bought them. At his first inspection he found them all faulty – rejecting some because they were too slight, some because they were lame, and one because it was an old coach-horse. With the difficulty of getting horses came also the difficulty of procuring forage. The contract for the horses of the Traynes for Chester and Ireland reached the unprecedented sum of fifteen pence per horse for each day.

To add to the other troubles of the new Board, the Chief Firemaster and Engineer (Sir Martin Beckman), with all the keenness and zeal of a renegade, kept worrying it about the state of the various Forts and Barracks; whose defects, he assured the Board, he had repeatedly urged on the two preceding monarchs, but without avail, on account of the deficiency of funds. "Berwick," he begged to assure the Board, "is getting more defenceless every year, and will take 31,000l. to be spent at once to prevent the place from being safely insulted." For six years past he assured the Board that Hull had been going to ruin: the earthworks had been abused by the garrison, who had suffered all sorts of animals to tread down the facings, and had, in the night-time, driven in cattle, and made the people pay money before they released them; and when they turned the cattle and horses out, they drove them through the embrasures and portholes, and so destroyed the facings, that, without speedy repair and care, his Majesty would certainly be obliged to make new ones.

The bomb-vessels also occupied the attention of the Board. More practical Artillerymen were required than could be granted without greatly increasing the permanent establishment. So a compromise was made; and a number of men were hired and appointed practitioner bombardiers, at the same rate of pay as others of the same rank, viz. 2s. per diem, but with the condition that the moment their services were no longer required they would be dispensed with.

There were calls, also, from the West Indies on the sore-pressed Board. A train of brass Ordnance was sent there, to which were attached the following, among other officials: – A Firemaster, at 10s. a day; a Master-Gunner, at 5s.; Engineers, at various rates, but generally 10s., who were ordered to send home frequent reports and sketches; Bombardiers, at 2s. 6d.; and a proportion of Gunners and Matrosses, at 2s. and 1s. 6d. per diem respectively, whose employment was guaranteed to them for six months at least.

As if the Admiralty, the horsedealers, the West Indies, Scotland, Ireland, and unseasonable zeal were not enough, there must come upon the scene of the Board's deliberations that irrepressible being, the "old soldier." The first Board of William and Mary was generous in its dealings with its officials almost to a fault. This is a failing which soon reaches ears, however distant. Several miners absent in Scotland, hoping that in the confusion the vouchers had been mislaid, complained that they were in arrears of their pay, "whereby," said the scoundrels, "they were discouraged from performing their duties on this expedition." Enquiries were made by the Board, and in the emphatic language of their minute, it was found "that they lied, having been fully paid up."

When the time came for the Duke to shake off the immediate worries of the office, as he proceeded to Chester and to Ireland, his relief must have been great. With him he took the chief waggon-master to assist in the organization of the train in Ireland, leaving his deputy at the Tower to perform his duties. The suite of the Master-General on his ride to Chester included six sumpter mules with six sumpter men, clad in large grey coats, the sleeves faced with orange, and "the coats to be paid for out of their pay."

Only two more remarks remain to be made. The proportion of drivers to the horses of William's train of Artillery in Ireland may be gathered from an order still preserved directing a fresh lot of horses and men to be raised in the following proportions: one hundred and eighty horses; thirty-six carters, and thirty-six boys.

Next, the dress of the train can be learned from the following warrant, ordering: —

"That the gunners, matrosses, and tradesmen have coates of blew, with Brass Buttons, and lyned with orange bass, and hats with orange silk Galoome. The carters, grey coates lyned with the same. That order be given for the making of these cloaths forthwith, and the money to be deducted by equal proportions out of their paye by the Treasurer of the Trayne."

(Signed) "Schomberg."

From a marginal note, we learn that the number of gunners and matrosses with the train was 147, and of carters, 200; these being the numbers of suits of clothes respectively ordered.

It was with this train to Ireland that we find the first notice of the kettledrums and drummers ever taking the field.7

CHAPTER IV.

Landmarks

In the chaotic sea of warrants, correspondence, and orders which represents the old MSS. of the Board of Ordnance prior to the formation of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, there are two documents which stand out like landmarks, pointing to the gradual realization of the fact that a train of Artillery formed when wanted for service, and disbanded at the end of the campaign, was not the best way of making use of this arm; and that the science of gunnery, and the technical details attending the movement of Artillery in the field, were not to be acquired intuitively, nor without careful study and practice during time of peace.

The first relates to the company of a hundred fee'd gunners at the Tower of London, whose knowledge of artillery has already been described as most inadequate, and whose discipline was a sham. By a Royal Warrant dated 22nd August, 1682, this company was reduced to sixty in number by weeding out the most incapable; the pay, which had up to this time averaged sixpence a day to each man, was increased to twelve-pence; but in return for this augmentation, strict military discipline was to be enforced; in addition to their ordinary duties at the Tower, they were to be constantly exercised once a week in winter, and twice a week in summer by the Master-Gunner of England; they were to be dismissed if at any time found unfit for their duties; and a blow was struck at the custom of men holding these appointments, and also working at their trades near the Tower, by its being distinctly laid down that they were liable for duty not merely in that Fortress, but also "in whatever other place or places our Master-General of the Ordnance shall think fit."

This was the first landmark, proclaiming that a nucleus and a permanent one of a trained and disciplined Artillery force was a necessity. Money was not plentiful at the Ordnance Board under the Stuarts, as has already been stated; so as time went on, and it was found necessary to increase the educated element, – the fireworkers, petardiers, and bombardiers, – it was done first by reducing the number of gunners, and, at last, in 1686, by a grudgingly small increase to the establishment.

In 1697, after the Peace of Ryswick, there was in the English service a considerable number of comparatively trained artillerymen, whose services during the war entitled them to a little consideration. This fact, coupled with the gradual growth in the minds of the military and Ordnance authorities of the sense of the dangers that lay in the spasmodic system, and the desirability of having some proportion of artillerymen always ready and trained for service and emergency, brought about the first – albeit short-lived – permanent establishment, in a regimental form, of artillery in England. The cost of the new regiment amounted to 4482l. 10s. per annum, in addition to the pay which some of them drew as being part of the old Ordnance permanent establishment. But before a year had passed, the regiment was broken up, and a very small provision made for the officers. Some of the engineers, gentlemen of the Ordnance, bombardiers, and gunners were added to the Tower establishment, and seventeen years passed before this premature birth was succeeded by that of the Royal Regiment of Artillery.

But this landmark is a remarkable one; and in a history like the present deserves special notice. Some of the officers afterwards joined the Royal Artillery; most of them fought under Marlborough; and all had served in William's continental campaign either by sea or land. Two of the captains of companies, Jonas Watson and William Bousfield, had served in the train in Flanders in 1694, and Albert Borgard, its adjutant, was afterwards the first Colonel of the Royal Artillery.

The staff of the little regiment consisted of a Colonel, Jacob Richards, a Lieutenant-Colonel, George Browne, a Major, John Sigismund Schmidt, an Adjutant, Albert Borgard, and a Comptroller: of these the first four had been serving on active service in Flanders. There were four companies, very weak, certainly, and containing men paid both on the old and new establishments. Each contained 1 captain, 1 first-lieutenant, 1 second-lieutenant, 2 gentlemen of the Ordnance, 2 sergeants, and 30 gunners. Of these the gentlemen of the Ordnance and 15 gunners per company were on the old Tower establishment. The names of the captains not mentioned above were Edward Gibbon, and Edmund Williamson.

There were also in the Regiment six engineers, four sub-engineers, two firemasters, twelve fireworkers, and twelve bombardiers.

When the regiment was reduced, the captains received 60l. per annum, the first and second lieutenants 50l. and 40l. per annum, the firemasters 60l., and the fireworkers 40l. These officers were described as belonging to the new establishment, in contradistinction to the old.

The time had now come when there was to be an establishment of Artillery in addition to these, whose school and arena were the campaigns of a great master of war, one who was to be the means, after a victorious career, of placing the stamp of permanence on what had as yet had but an ephemeral existence, – the regimental character as applied to Artillery forces in England.

CHAPTER V.

Marlborough's Trains

Although the description of campaigns which occurred before the regimental birth of the Royal Artillery is beyond the purpose and province of this history, yet so many of the officers and men who fought under the great Duke of Marlborough, or served in the various trains equipped by his orders for Gibraltar, Minorca, and Nova Scotia, afterwards were embodied in the regiment, that the reader must greet with pleasure any notice of the constitution of these Trains, as being in all probability typical of what the early companies of the Regiment would be when attached to Ordnance for service in the field.

The Duke of Marlborough was appointed Master-General of the Ordnance almost immediately after the accession of Queen Anne, and until the day of his death he evinced the warmest and most intelligent interest in everything connected with the Artillery Service.

The reader will remember that one of the first acts of Queen Anne was to declare war against France, with her allies the Emperor of Germany and the States-General. The declaration of war was not formally made until the 4th May, 1702, but preparations had been going on for a couple of months before with a view to commencing hostilities. On the 14th March, 1702, the warrant for the Train of Artillery required for the opening campaign was issued to the Earl of Romney, then Master-General. The number of pieces of Ordnance required was fixed at 34, including 14 sakers, 16 3-pounders, and 4 howitzers: and the personnel considered adequate to the management of these guns consisted of two companies of gunners, one of pioneers, and one of pontoon men, in addition to the requisite staff, and a number of artificers. Each company consisted of a captain, a lieutenant, a gentleman of the Ordnance, six non-commissioned officers, twenty-five gunners, and an equal number of matrosses. At this time the fireworkers and bombardiers were not on the strength of the companies as was afterwards the case. Two fireworkers and eight bombardiers accompanied this train.

The pioneers were twenty in number, with two sergeants, and there was the same number of pontoon men, with two corporals, the whole being under a Bridge-master. The staff of the train consisted of a colonel, a lieutenant-colonel, a major, a comptroller, a paymaster with his assistant, an adjutant, a quartermaster, a chaplain, a commissary of horse, a surgeon and assistant-surgeon, and a provost-marshal. The kettledrummer and his coachman accompanied the train. There were also present with this train a commissary of stores with an assistant, two clerks, twelve conductors, eight carpenters, four wheelwrights, three smiths, and two tinmen.

The rates of pay of the various attendants are again worthy of note. The master carpenter, smith, and wheelwright got a shilling daily more than the assistant-surgeon, who had to be happy on 3s. per diem; the provost-marshal and the tinman each got 2s. 6d.; the clerks and the gentlemen of the Ordnance were equally paid 4s.; the chaplain, adjutant, and quartermaster received 6s. each; a lieutenant received the same, and a fireworker 2s. less. The pay of the higher ranks was as follows: – Colonel, 1l. 5s.; lieutenant-colonel and comptroller, each 1l.; major, 15s.; and paymaster, 10s. The gunners received 1s. 6d.; matrosses, pioneers, and pontoon-men, each, 1s..

It was the month of June, 1702, before this train landed in Holland, and on the 30th of that month it joined the Allied Army at Grevenbrouck, having had an addition made to it of four guns before leaving England. The pay of the train amounted to 9289l. 5s. per annum; and the ammunition with which they commenced the campaign consisted of 3600 rounds, of which 3000 were round shot, and 600 canister or case. They also carried 31 boxes of small hand-grenades, and 754 grenades of a larger description. The conduct in the field of this train was admirable. During the whole campaign of 1702, their fire is described as having been carried on with "as much order, despatch, and success as ever before was seen."

And then, in the luxurious way in which war was made in those days, the army went into winter quarters.

For the campaign of 1703, it was decided to augment the train of Artillery, and a warrant to that effect was issued to the Ordnance on the 8th February, 1703. The only difference in the personnel of the train was the addition of five gunners to each company, they now outnumbering the matrosses for the first time. The addition to the guns consisted of six demi-culverins.

In March of this year, the Board of Ordnance was also called upon to fit out two bomb-vessels for service in the Channel; and as the bomb-service remained long after the Regiment existed, it may be interesting to the reader to learn the armament of these vessels. It consisted of three 13-inch brass sea-service mortars, one vessel carrying two. For ammunition they carried 1200 shells and 40 carcasses, – besides 248 barrels of powder. The Artillerymen on board were represented by three fireworkers, six bombardiers, and two artificers; but as provision was made for ten, not eleven, "small flock bedds, bolsters, ruggs, and blankets," it is to be presumed either that one of the number was above the necessity of sleep, or that a certain socialism existed in the matter of beds, which admitted of the individual on duty adjourning to the bed vacated by the man who relieved him.

In a later warrant of the same year, when a larger number of these vessels was ordered to the Mediterranean, a Firemaster at 8s. per diem was placed over the fireworkers, and a few conductors of stores were added.

A further addition was made in 1704 to the train in Holland, showing the increased appreciation of the services of the Artillery. It consisted of six brass culverins and four 3-pounders, with two gentlemen of the Ordnance, sixteen gunners, and sixty of their assistants, the matrosses. Two more artificers were also added.

An idea of the Artillery train under Marlborough's own command can be obtained from the above dry details, and when compared with the proportions of Artillery in the armies of more recent times, Marlborough's train excites a smile. The value of Artillery in the field had not yet been learned, while the cumbrous nature of its equipment was painfully present to every General. Not until Napoleon came on the scene did Artillery assume its proper place in European armies; not until the Franco-German War of 1870 did it assume its proper place in European opinion.

But equally interesting with the details of the train which Marlborough commanded are those of the trains, which, as Master-General of the Ordnance, he prepared for expeditions and services under other commanders, in the stormy time which was hushed to rest by the Peace of Utrecht.

When the expedition to Portugal, ordered in 1703, but which did not take place till the following year, was decided on, the armament selected consisted merely of five brass sakers, and one 5¼-pounder.