полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

The arming of all men-of-war belonged to the Ordnance; indeed, the office was created for the Navy, although, in course of time, Army details almost entirely monopolized it. Although obliged to act on the requisitions of the Lord High Admiral, their control in their own details, and over the gunners of the ship as regarded their stores, was unfettered. The repairing of the ships, and to a considerable extent their internal fittings, were part of the Board's duties; but it is to be hoped that the technical knowledge of some of their officials exceeded that possessed by the Masters-General. A letter is extant from one of these distinguished individuals, written on board the 'Katherine' yacht, in 1682, to his loving friends, the principal officers of the Ordnance. "I desire" he wrote, "you would give Mr. Young notice to proceed no further in making ye hangings for ye great bedstead in ye lower room in ye Katherine yacht, till ye have directions from me."

But the Naval branch of the Board's duties is beyond the province of the present work. Of the Military branch much will be better described in the chapters concerning the old Artillery trains, the Royal Military Academy, and in the general narrative of the Royal Artillery's existence as a regiment. A few words, however, may be said here with reference to their civil duties, once of vast importance, but, with the naval branch, swallowed up, like the fat kine of Pharaoh's dream, by the military demands which were constantly on the increase, and were fostered by the military predilections of the Masters and Lieutenants-General.

The civil duties have been well and clearly defined by Clode in his 'Military Forces of the Crown,' vol. ii. He divides into duties – 1. As to Stores; 2. As Landowners; 3. As to the Survey of the United Kingdom; 4. As to Defensive Works; 5. As to Contracts; and 6. As to Manufacturing Establishments.

Of the first of these it may be said that their system was excellent. Periodical remains were taken (the oldest extant being dated April, 1559), and a system of issues and receipts was in force which could hardly be improved upon.

In their capacity as Landowners, the members of the Board were good and cautious stewards; but as buyers of land, their characteristic crops up of thinking but little of other men's feelings or convenience. Perhaps their line of action in this respect can be best illustrated by an anecdote which comes down over many years in the shape of an indignant and yet pitiful remonstrance. It was in good Queen Anne's time, and the Board had formed a scheme for fortifying Portsmouth. They appointed Commissioners to arrange the situation of the various works, and to come to terms with the landowners. These gentlemen did their duty; and, among others, one James Dixon was warned that some land on which he had recently built a brewhouse would be required for the Board's purposes. A jury was empanelled, and assessed the value of the whole at 4000l. When James Dixon built his brewhouse, he had borrowed money on mortgage: the interest would, he believed, be easily paid, and the principal of the debt gradually reduced by the earnings of the brewery. But after the jury sat, not a drop of beer was brewed: no orders could be taken, with the fear hanging over him that he must turn out at any moment; nor could he introduce additional improvements or fixtures after the assessment had been made, as he would never receive a farthing for them over the first valuation. Little knowing the admirable system of official management in which an English department excels, he sat waiting for the purchase-money. One month passed after another: Christmas came, and yet another, and another, and the only knocks at James Dixon's door were from the angry creditor demanding his money. At last, after waiting four years, – the grey hairs thickening on the unhappy brewer's head, – the knock of a lawyer's writ came; and before the Master of the Rolls his miserable presence and story were alike demanded. The narrative ends abruptly with a petition from him for six months' grace. Even then hope was not dead in him; and he babbled in his prayer that "he was in hopes by this time "to have redeemed it out of the 4000l. agreed to be paid yr Petitioner as aforesaid."

In the course of our story we shall find many such lives crushed beneath the wheels of an official Juggernaut. Alas! that Juggernaut is still a god!

'The Survey of the United Kingdom' will be the most honourable vehicle for transmitting to posterity the story of the Board's existence; for, although not yet completed, to the Board is due the credit of originating a work whose national value can hardly be over-estimated. The defensive works erected under the Ordnance already live almost in history, so rapidly has the science of fortification had to move to keep pace with the strength of attack. Their contracts showed but little favouritism, and, on the whole, were just: they included everything, from the building of forts to the manufacture of gunpowder and small arms; and, in peace and war, they reached nearly over the whole civilized world. With this extensive area came the necessity for representatives of the Board at the various stations, – who were first, and wisely, civilians, three in number; afterwards, most foolishly, owing to the increasing military element at the Board, two soldiers, the commanding officers of Artillery and Engineers, and one civilian. And as no man can serve two masters, it was soon apparent that the military members could not always serve their local General and their absent Board; discipline was not unfrequently strained; jealousy and ill-will supervened; and when the death of the Board sounded the knell of the Respective officers, as they were termed, there can be no doubt that it removed an anomaly which was also a danger. Under the new and existing system, the commanding officers of Artillery and Engineers occupy their proper places: they are now the advisers of their General, not his critics: and the door is opened for the entry of the officers of the scientific corps upon an arena where civilian traditions are unknown or powerless.

Of the manufacturing departments of the Ordnance, what has to be said will come better in its place in the course of the narrative.

In summing up, not so much the contents of this Chapter, which is necessarily brief, as the study of the Board's history, the following are the ideas presented to the student's mind: – The Board of Ordnance formed a standard of political excellence, – which it endeavoured to follow when circumstances permitted, – of financial and economical excellence, which it planted everywhere among its subordinates for worship, but which was not allowed the same adoration in its own offices in the Tower. It saved money to the country legitimately by an admirable system of check and audit – illegitimately too often by a false economy, which in the end proved no economy at all; it obstructed our Generals in war, and hampered them in peace: it was extravagant on its own members and immediate retainers to an extent which can only be realized by those who study the evidence given before the Parliamentary Commission of 1810-11. Jobbery existed, but rarely secret or underhand; and its extensive patronage was, on the whole, well and fairly exercised. And although every day shows more clearly the wisdom of removing from under the control of a Board that part of our army, the importance of which is made more apparent by every war which occurs, yet the Artilleryman must always remember with kindly interest that it was to this board and its great Master (Marlborough) that his Regiment owes its existence, that to it we owe a nurture which was sometimes too detailed and careful, but under which we earned a reputation in many wars; and that, after a long peace, it placed in the Crimea, for one of the greatest and most difficult sieges in history, – difficult for other reasons than mere military, – the finest siege-train of Artillery that the world has ever seen. In command of the English Army, during this war, the Board's last Master died; and in the list which preceded him, and with which this chapter closes, will be found names which would almost atone for the worst offences ever committed by the Board over which their owners presided.

List of the Masters-General of the OrdnanceThe most recent list of these distinguished officials is that published in Kane's 'List of Officers of the Royal Artillery.' In it all the Masters before the reign of Henry VIII. are ignored, as being merely commanders of the Artillery on expeditions or in districts. But this seems somewhat stern ruling. Undoubtedly Henry VIII. reorganized the Ordnance Department, and defined the position of the Master, as never had been done before, and the sequence of the Masters from his reign is clear and intelligible. But before his time there were not merely Masters of the Ordnance on particular expeditions, but also for life; and there were certainly Offices of the Ordnance in the Tower. It has, therefore, been thought advisable in the following list to prefix a few names, which seem deserving of being included, although omitted in 'Kane's List.'

The earliest of whom there is any record is

Rauf Bigod, who was appointed on 2nd June, 1483, "for life." His life does not, however, seem to have been a very long one, for we find

Sir Richard Gyleford, who was appointed in 1485.

Sir Sampson Norton was undoubtedly Master of the Ordnance, appointed in 1513, as has been proved by extant MSS.

The next one about whom there is any certainty would appear to be the one who heads 'Kane's List' —

Sir Thomas Seymour, who was appointed about 1537. Other lists show Sir Christopher Morris as Master at this time; but there seems little doubt that he was merely Lieutenant of the Ordnance, although a distinguished soldier, and frequently in command of the Artillery on service.

If one may credit 'Dugdale's Baronage,' the next in order was

Sir Thomas Darcie (afterwards Baron Darcie), appointed in 1545: but if so, he merely held it for a short time, for we find him succeeded by

Sir Philip Hoby, who was appointed in 1548.

'Grose's List' and others interpolate Sir Francis Fleming, as having been appointed in 1547; but this is undoubtedly an error, and his name wisely rejected by the author of 'Kane's List,' where it is placed, as it should be, in the list of Lieutenants of the Ordnance. There is a folio of Ordnance accounts still in existence, extending over the period between 29th March, 1547, and the last day of June, 1553, signed by Sir Francis Fleming, as Lieutenant of the Ordnance.

The next in rotation in the best lists is

Sir Richard Southwell, Knight, shown by 'Kane's List' as appointed in February, 1554, and, by certain indentures and Ordnance accounts which are still extant, as being Master of the Ordnance, certainly in 1557 and 1558.

The next Master held the appointment for many years. He was

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick, and can be proved from indentures in the possession of the late Craven Ord, Esq., which are probably still in existence, and from which extracts were made in 1820 by the compiler of a manuscript now in the Royal Artillery Library, to have been appointed on the 19th February, 1559, and to have held the office until 21st February, 1589, over thirty years.

Possibly owing to the difficulty of finding any one ready to undertake the duties of one who had had so much experience – a difficulty which occurred more than once again – the office was placed in commission after 1589, probably until 1596. From 'Burghleigh's State Papers' we learn that the Commissioners were, the Lord Treasurer, the Lord High Admiral, the Lord Chamberlain, and Vice-Chamberlain Sir J. Fortescue.

On 19th March, 1596, Robert, Earl of Essex, was appointed Master of the Ordnance, and held the appointment until removed by Elizabeth, in 1600. No record of a successor occurs until the 10th September, 1603, when

Charles, Earl of Devonshire, was appointed. He died in 1606, and was succeeded by

Lord Carew, appointed Master-General throughout England, for life, in 1608. He was created Earl of Totnes in 1625, and died in 1629. From a number of Ordnance warrants and letters still extant, there can be no doubt that he held the office until his death. For a year after, until 5th March, 1630, we learn, from the Harleian Manuscripts, that there was no Master-General. On that date

Howard Lord Vere was appointed, and held office until the 2nd September, 1634, when

Mountjoy, Earl of Newport, was appointed.

Then came the troubles in England – the Revolution, the Commonwealth, and at last the Restoration. Lord Newport seems to have remained Master-General the whole time; for on Charles II. coming to the throne, he issued directions specifying, "Forasmuch as the Earl of Newport may, by Letters Patent from our Royal Father, pretend to the office of our Ordnance, We, for weighty reasons, think fit to suspend him from said charge, or anything belonging thereto; and Our Will is that you prepare the usual Bill for his suspension."

On the 22nd January, 1660, a most able Master-General was appointed, whose place the King afterwards found it most difficult to fill. He was

Sir William Compton, Knight, and he remained in office until his death. By letters patent, on the 21st October, 1664, specifying that he had not determined with himself to supply the place of office of his Master of the Ordnance, then void by the death of Sir William Compton, and considering the importance of his affairs at that time to have that service well provided for, the King appointed as Commissioners to execute the office of Master of the Ordnance

John, Lord Berkly of Stratton, }

Sir John Duncombe, Knight, and }

Thomas Chicheley. }

This Commission lasted until the 4th June, 1670, when the last-named Commissioner (now Sir Thomas Chicheley, Knight), was appointed Master of the Ordnance, and in the warrant for his appointment, which is now in the Tower Library, there is a recapitulation of the names of previous Masters, which includes one – placed between Sir Richard Southwell and the Earl of Essex – which does not appear in any other list, but which one would gladly see included —

Sir Philip Sidney.

After the death of Sir Thomas Chicheley, the office was again placed in Commission, the incumbents being

Sir John Chicheley, son of the late Master,

Sir William Hickman, and

Sir Christopher Musgrave, the last-named of whom afterwards became Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance. This Commission lasted from 1679 to 8th January, 1682, when the celebrated

"George, Lord Dartmouth," became Master, having held the office of Lieutenant-General under the Commission from 1st July, 1679, as plain Colonel George Legge. He remained in office until after the Revolution of 1688, when he forfeited it for his adherence to the King. His successor, appointed by William III. in 1689, and afterwards killed at the Battle of the Boyne, rejoiced in the following sounding titles:

Frederick, Duke de Schomberg, Marquis of Harwich, Earl of Brentford, Baron of Teys, General of their Majesties' Forces, Master-General of their Majesties' Ordnance, Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, Grandee of Portugal, General of the Duke of Brandenburg's forces, and Stadtholder of Prussia.

After his death, the Master-Generalship remained vacant until July, 1693, when it was conferred upon

Henry, Viscount Sidney, afterwards Earl of Romney, who held it until 1702. He was succeeded, almost immediately on Queen Anne's accession, by her favourite, the great

John, Earl of Marlborough, who held the appointment until he fell into disgrace with the Queen, when he resigned it, with his other appointments, on 30th December, 1711. He was succeeded by

Richard, Earl Rivers, who, after six months, was followed, on 29th August, 1712, according to the British Chronologist, or on the 1st July, 1712, according to Kane's List, by

James, Duke of Hamilton, who was killed in a duel in November of the same year.

For two years the appointment remained vacant, but in 1714 it was again conferred upon

John, now Duke of Marlborough, who held it until his death, in 1722. He was succeeded, as follows, by

William, Earl of Cadogan, on 22nd June, 1722, and by

John, Duke of Argyle and Greenwich, on 3rd June 1725.

At this period there is an unaccountable confusion among the various authorities. The 'British Chronologist' and the 'Biographia Britannica' make the list run as follows: – The Duke of Argyle and Greenwich was succeeded, in 1740, by John, Duke of Montague, and resumed office again, for three weeks, in 1742, when, for the last time, he resigned all his appointments, being again succeeded by the same Duke of Montague, who continued to hold the office until 1749, when he died.

'Grose's List,' on the other hand, makes the Duke of Argyle's tenure of office expire in 1730, instead of 1740, and makes no allusion to his brief resumption of the appointment in 1742, and 'Kane's List' has followed this. It is possible that for the brief period that he was in office the second time, no letters patent were issued for his appointment, which would account for its omission in most lists; but the difference of ten years in the duration of the first appointment is more difficult to account for. There is no doubt that, in 1740, the Duke of Argyle resigned all his appointments for the first time, but it is not stated whether the Master-Generalship was one, although it has been assumed. On the other hand, he might have been away during these ten years to a great extent, or allowed his officers of the Ordnance to sign warrants, thus giving an impression to the casual student that he no longer held office. The manuscript in the Royal Artillery Library, already referred to, bears marks of such careful research, that one is disposed to adopt its reading of the difficulty, which is different from that taken by Grose's and Kane's Lists, and agrees with the other works mentioned above.

After the death of the Duke of Montague, the office remained vacant until the end of 1755, when it was conferred upon

Charles, Duke of Marlborough, who held it until his death, on 20th October, 1758.

During the vacancy immediately preceding the appointment of the last-named Master-General, Sir J. Ligonier had been appointed Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, and for four years had performed the duties of both appointments, – acted as Colonel of the Royal Artillery, and Captain of the Cadet Company. A few months after the death of the Duke of Marlborough – namely, on the 3rd July, 1759 – he was appointed Master-General, being by this time

Field-Marshal Viscount Ligonier. He was succeeded, on the 14th May, 1763, by

John, Marquis Granby, who held it until 17th January, 1770, when we find that he resigned all his appointments, except the command of the Blues. For nearly two years the office remained vacant, and on the 1st October, 1772, it was conferred upon

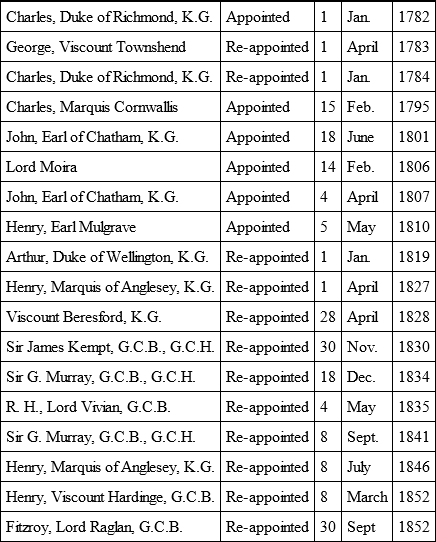

George, Viscount Townshend, whose tenure of office extended over nearly the whole of that anxious period in the history of England which included such episodes as the American War of Independence and the great Siege of Gibraltar. The sequence of the remaining Masters may be taken from Kane's List, and is as follows: —

On the abolition of the Board of Ordnance, the command of the Royal Artillery was given to the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces at that time,

Field-Marshal Viscount Hardinge, G.C.B. His successor (appointed Colonel of the Royal Artillery on the 10th May, 1861, and at this date holding that office) was

H.R.H. the Duke of Cambridge, K.G., &c. &c., now Field-Marshal Commanding-in-Chief.

CHAPTER II.

The Infancy of Artillery in England

The term Ordnance was in use in England before cannon were employed; and it included every description of warlike weapon. The artificers employed in the various permanent military duties were called officers of the Ordnance.

The first record of cannon having been used in the field dates from Henry III.; and with the increasing skill of the founders the use of cannon speedily became more general. But the moral influence of the guns was far beyond their deserts. They were served in the rudest way, and their movements in the field and in garrison were most uncertain, yet they were regarded with superstitious awe, and received special names, such as "John Evangelist," the "Red Gun," the "Seven Sisters," "Mons Meg," &c. In proportion to the awe which they inspired was the inadequate moral effect produced on an army by the loss of its artillery, or by the capture of its enemy's guns.

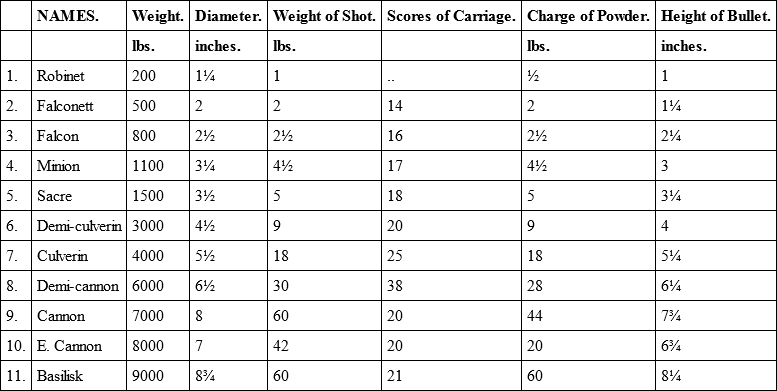

In the earliest days cannon were made of the rudest materials, – of wood, leather, iron bars, and hoops; but as time went on guns of superior construction were imported from France and Holland. The first mention of the casting in England of "great brass cannon and culverins" is in the year 1521, when one John Owen began to make them, "the first Englishman that ever made that kind of Artillery in England." The first iron guns cast in this country were made by three foreigners at Buckstead in Sussex, in the year 1543. In this same year, the first shells were cast, for mortars of eleven inches calibre, described as "certain hollow shot of cast iron, to be stuffed with fireworks, whereof the bigger sort had screws of iron to receive a match, and carry fire to break in small pieces the same hollow shot, whereof the smallest piece hitting a man would kill or spoil him." The following table2 gives the names, weights, and charges of the guns which were in general use in the year 1574. There were, in addition to these, guns called Curtals or Curtaux, Demicurtaux, and Bombards: —

Among the earliest occasions recorded of the use of Artillery by the English, were the campaigns in Scotland of Edward II. and Edward III.; the capture of Berwick by the latter monarch in 1333; his campaigns in Flanders and France in 1338-39-40; his siege of Vannes in 1343; his successful raid in Normandy in 1346; the battle of Cressy on the 26th August in that year, when the fire of his few pieces of cannon is said to have struck a panic into the enemy; the expedition to Ireland in 1398; Henry IV.'s defeat of the French in Wales, in 1400; another successful siege of Berwick in 1405; the capture of Harfleur in 1415; and the battle of Agincourt on the 25th October of that year; the sieges of Tongue and Caen in 1417; of Falaise and other towns in Normandy in 1418; concluding with the capitulation of Cherbourg and Rouen after protracted sieges, stone projectiles being thrown from the cannon with great success; the engagements between Edward IV. and Warwick, when Artillery was used on both sides; the expedition to France in 1474, and to Scotland in 1482, when yet another successful siege of Berwick took place, successful mainly owing to the Artillery employed by the besieging force; the capture of Sluis, in Flanders; and the attack on Calais and Boulogne in 1491. In the sixteenth century may be enumerated the expedition to Flanders in 1511, in aid of the Duchess of Savoy; the Siege of Térouenne and Battle of the Spurs in 1513; the Siege of Tournay; the Battle of Flodden Field, where the superior accuracy of the English Artillery rendered that of the Scotch useless; the descent on the coast of France and capture of Morlies in 1523; the Siege of Bray and Montedier in 1524; the siege of Boulogne in 1544; the expedition to Cadiz under the Earl of Essex in 1596, and that to the Azores in 1597. In the next century, daring the Civil War, and in all Cromwell's expeditions, the use of Artillery was universal; and the part of the century after the Restoration will be alluded to in a subsequent chapter.

The use, therefore, of Artillery by the English has existed for centuries; but, – regarding it with modern eyes, its application would better deserve the term abuse. Nothing strikes the student so much as the absence of the scientific Artillery element in the early trains; and this feeling is followed by one of wonder at the patience with which our military leaders tolerated the almost total want of mobility which characterized them. Not until the last decade of the eighteenth century was the necessity of mobility officially recognized, by the establishment of the Royal Horse Artillery; and it took half a century more to impress upon our authorities that a Field Battery might not unreasonably be expected to move occasionally faster than a walk.