полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

It is difficult, in reviewing such a period as the last fifteen years have been in the history of Artillery in England – so full of improvements in every way – to single out any one of these as more worthy of mention than the rest; but when posterity comes to review it dispassionately, the improvement in equipment and mobility of our Field Artillery will most probably be considered the prominent feature of the time. And these are the very qualities which for centuries remained in England unimproved and stagnant. The eighteenth century saw Artillery conducted by drivers, not under military discipline, nor marked by distinctive costume; who not unfrequently fled with their horses during the action, leaving the gunners helpless, and the guns at the mercy of the enemy. In this year, 1872, our drivers go into action unarmed, it being considered that the possession of defensive weapons might distract their attention from their horses. But we do not commit the old error of using men not under martial law. A driver who, on an emergency, finds himself with his whip merely to defend him, may possibly feel aggrieved: but however far he may run away, he cannot escape the embrace of the Mutiny Act, and is as liable to punishment as the man who deserts before the enemy, after his country has sent him into the field armed from head to foot.

In the very earliest days of Artillery in England, the number of gunners borne on permanent pay on the books of the Ordnance bore a very small proportion to the artificers so borne. With the increasing use of cannon, an increase in the number of artillerymen took place, but by no means pari passu: and, as towns in England became gradually fortified, a small number of gunners in each was found to be necessary to protect and take care of the stores, and to fire the guns on high days and holidays. In 1344, although no fewer than 321 artificers and engineers were borne on the books of the Ordnance in time of peace, only twelve gunners and seven armourers appear. In 1415, at the Siege of Harfleur, there were present 120 miners, 130 carpenters, and 120 masons; but only 25 master, and 50 servitor gunners – the latter corresponding probably to the matrosses of a later date. At the Siege of Tongue, in 1417, no less than 1000 masons, carpenters, and labourers were present, but only a small number of gunners. At this time, the driving of the guns, the placing them in position, and shipping and unshipping them, devolved on the civil labourers of the trains, and there was a military guard to escort the guns on the march. The gunner's duty seems to have been a general supervision of gun and stores, and the laying and firing it when in action. He was the captain of the gun in war – its custodian in peace. After the fifteenth century there was a marked increase in the number of artillerymen in the trains, although still totally inadequate. For example, in the train ordered on service in France, in 1544, where the civil element was represented by 157 artificers, 100 pioneers, and 20 carters, there were no less than 2 master-gunners, 264 gunners, and a special detachment of 15 gunners, for the guns placed immediately round the King's tent. The principal officers of the Ordnance also accompanied the expedition.

There was a distinction between the gunners of garrisons and those of the trains, as regarded the source of their pay, or rather its channel. At first, both were paid from the Exchequer; but after the proper establishment of an Ordnance Department at the Tower, the gunners of the various trains were paid by it, the others receiving their salaries as before. The company of fee'd gunners at the Tower of London differed from the gunners of other garrisons in receiving their pay from the Ordnance directly. It must not be imagined, however, that the gunners of garrisons were beyond the control of the Board of Ordnance because their pay was not drawn on the Ordnance books. Not merely had the Master of the Ordnance the nomination of the gunners of garrisons, but the power also of weeding out the useless and superannuated. The instance given in the Introductory Chapter of this volume, shows how directly they were under the Board in matters of discipline; and although, as a matter of Treasury detail, their pay was drawn in a different department, a word from the Ordnance Office could stop its issue to any gunner in any garrison who was deemed by the Board to have forfeited his right to it in any way. It was not until 1771, long after the formation of the Royal Artillery, that these garrison gunners were incorporated into the invalid companies of the regiment; and at the present date they are represented by what is called the Coast Brigade of Artillery. The pay of the old gunners of garrisons depended on the fort in which they resided. Berwick, for example, as an important station, was also one in which the gunner's pay was higher. In the reign of Edward VI. we find the average pay of a master-gunner was 1s. a-day, and of the gunners, from 4d. to 1s. Later, the pay of the master-gunner was raised to 2s. a-day, and that of the gunners rarely fell below 1s. In time of war, the pay of the gunners of the trains far exceeded the above rates. The senior master-gunner was styled the Master-Gunner of England. From 2s. a-day, which was the pay of this official in the sixteenth century, it rose to 160l. per annum, and ultimately to 190l. His residence and duties lay originally in the Tower, and chiefly among the fee'd gunners at that station; but after Woolwich had attained its speciality for Artillery details, quarters were allotted to him there in the Manor House. Among the oldest Master-Gunners of England whose names are recorded may be enumerated Christopher Gould, Richard Webb, Anthony Feurutter3 or Fourutter,4 Stephen Bull, William Bull, William Hammond, John Reynold, and John Wornn – all of whom held their appointments in the sixteenth century, and the majority of them by letters patent from Elizabeth. From the fact that in the wording of their appointments two of the above are particularized as soldiers by profession, it would appear that the others were not so; and it is more probable that they were chosen for their knowledge of laboratory duties, and of the "making of pleasaunt and warlike fireworks."

The company of fee'd gunners at the Tower, which might be supposed to have had some military organization, really appears to have had little or none. Their number in Edward VI.'s reign was 58, with a master-gunner; but gradually it was increased to 100, which for many years was the normal establishment. They were supposed to parade twice a week, and learn the science of gunnery, under the Master-Gunner of England; but their attendance was so irregular, and their ignorance of their profession so deplorable, that a strong measure had to be adopted, to which allusion will be made in a later chapter. Colonel Miller, in his researches among the warrants appointing the gunners, found some venerable recruits – who can hardly have been of much value in the field – of ages varying from sixty-four to ninety-two. There is no doubt that these appointments were frequently sold, or given in return for personal or political services, without any regard to the capability of the recipient. The clerks at the Ordnance Office had their fees for preparing these men's warrants, whose wording of the duties expected of the nominee must have frequently read like a grotesque satire. The situations were desirable because they did not interfere with the holders continuing to work at their trades near the Tower; and if the gunners were ordered to Woolwich for the purpose of mounting guns, or shipping and unshipping stores, they received working pay in addition to their regular salaries. It was from their ranks that the vacancies among master-gunners and gunners of garrisons were almost invariably filled.

When a warlike expedition had been decided upon, the Master of the Ordnance was informed what size of a train of Artillery was required; but he was permitted to increase or decrease its internal proportions as he thought fit. To him also was left the appointment of all the officers and attendants of the train; and, with the exception of any belonging to the small permanent establishment, it was understood that the services of any so appointed were only required while the expedition lasted. This spasmodic method of organizing the Artillery forces of this country was sufficient to account for the want of progress in the science of gunnery, and the equipments of our trains, which is apparent until we reach the commencement of the eighteenth century. But it took centuries of stagnation, and of bitter and shameful experience, to teach the lesson that Artillery is a science which requires incessant study, that such study cannot be expected unless from men who can regard their profession as a permanent one, and the study as a means to an end; and that, even admitting the possibility of such study being carried on by men in the hope of occasional employment, it would be too theoretical, unless means of practice and testing were afforded, beyond the power of a private individual to obtain. Nor could habits of discipline be generated by occasional military expeditions, which, to an untrained man, are more likely to bring demoralization; it is during peace-service that the discipline is learnt which is to steady a man in the excitement and hardships of war.

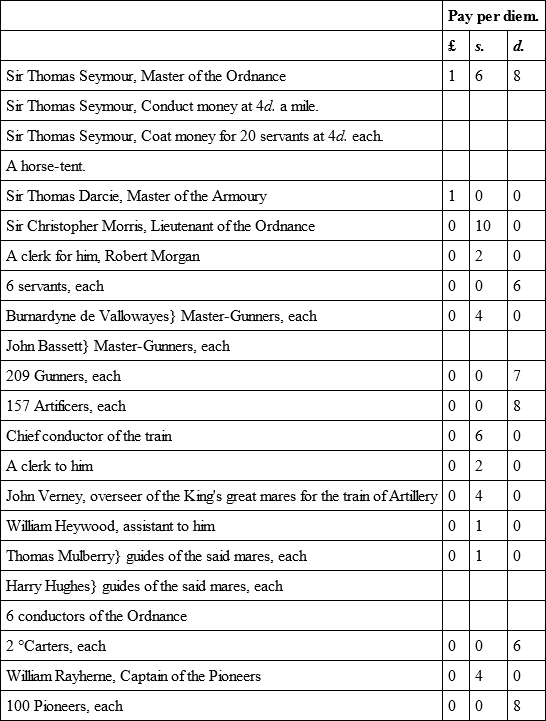

As samples of the trains of Artillery before the Restoration, the following, of various dates, may be taken: and an examination of the constituent parts will well repay the reader.

The first is a train in the year 1544, already alluded to, and which was commanded by the Master of the Ordnance himself, Sir Thomas Seymour.

1. Train of Artillery ordered on Service in 1544.

John Rogers, of the privy ordnance and weapons.

15 Gunners appointed to the brass pieces about the King's tent.

55 Gunners appointed to the shrympes, with two cases each.

4 carpenters.

4 wheelers.

3 armourers.

Charles Walman, an officer employed to choose the gunpowder.

N.B.– The pioneers received 2s. a piece transport money from Boulogne to Dover, and conduct money from Dover to their dwelling-places – 4d. a mile for the captain, and ½ d. for every pioneer.

Harl. MS. 5753.

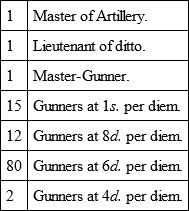

2. Establishment of a Small Train of Artillery in 1548.

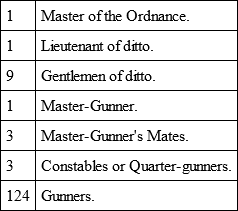

3. Establishment of a Train of Artillery in the year 1618.

4. Establishment of a Train of 22 pieces of Ordnance in the year 1620.

5. Establishment of a Train of 30 pieces in the year 1639.

It will be seen that in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5, the Artillery element is alone given. Nor are the proportions of the trains, and their constituent parts, such as to enable us to draw any fixed law from them. They are merely interesting – not very instructive. Table 1, on the other hand, is both interesting and instructive. The appearance of medical officers in the train of 1618, and of matrosses – a species of assistant-gunner – in that of 1639, will not have escaped the reader's notice.

In the next chapter we shall find that the presence of a man like Lord Dartmouth, and his predecessor, Sir William Compton, at the Ordnance, reveals itself in the greater method visible in the Artillery arrangements; and with the introduction of Continental artillerists, under William III., comes a greater experience of the value of Artillery, which nearly brought about, in 1698, that permanent establishment which was delayed by circumstances until 1716.

CHAPTER III.

The Restoration, and Revolution of 1688

The first step, of course, on the restoration of Charles II., was to undo everything in the Ordnance, and remove every official bearing the mark of the Protectorate. Having filled the vacant places with his own nominees, he seemed to consider his duty done, and, with one exception, the official history of the Ordnance for the next few years was a blank. The exception was the Company of Gunners at the Tower, which from 52, in 1661, rose to 90 in the following year, 98 in 1664, and then the old normal number 100.

But the work in the Department done by the Master-General, Sir William Compton, although not of a demonstrative character, was good and useful, and prepared the way for the reformations introduced by his more able successor, Lord Dartmouth. The Master-Gunners of England were now chosen from a higher social grade than before. In 166 °Colonel James Weymes held the appointment, followed in 1666 by Captain Valentine Pyne, and in 1677 by Captain Richard Leake. A new appointment was created for Captain Martin Beckman – that of Chief Firemaster. His skill in his department was rewarded by knighthood, and he held the appointment, not merely until the Revolution of 1688, but also under William III., having apparently overcome any scruples as to deserting his former masters. A Surveyor-General of the Ordnance, Jonas Moore by name, was appointed in 1669, who afterwards received permission to travel on the Continent to perfect himself in Artillery studies, for which purpose he received the sum of 100l. a year.

The names of the Ordnance in the various fortifications in England during the reign of Charles II. were as follows: —

Brass OrdnanceCannon of 8.

Cannon of 7.

Demi-cannon.

24 prs.

Culverings.

12 prs.

Demi-culverings.

8 prs.

6 prs.

Sakers.

Mynions.

3 prs.

Falcon.

Falconett.

Brass baces of 7 bores.

Inch and ¼ bore, and 7 other sizes.

Iron OrdnanceCannon of 7.

Demi-cannon.

24 prs.

Culverings.

12 prs.

Demi-culverings.

8 prs.

6 prs.

Sakers.

Mynions.

3 prs.

Falcon.

Falconett.

Rabonett.

Brass Mortar Pieces18½ in.5

16½ in.

13¼ in.

9 in.

8¾ in.

8 in.

7¾ in.

7¼ in.

6½ in.

6¼ in.

4½ in.

4¼ in.

Iron Mortar Pieces12½ in.

4¼ in.

Taken from Harl. MS. 4244.

The reader will observe the immense varieties of mortars, and the large calibres, compared with those of the present day. They were much used on board the bomb-vessels; but it is difficult to see the advantage of so many small mortars, varying so slightly in calibre.

From an account of some new ordnance made in 1671, we find that iron cannon of 7 were 10 feet long, and weighed on an average 63 cwt., or 9½ feet long, and weighing from 54 cwt. to 60 cwts. Iron culverings of 10 feet in length averaged 43 cwt. in weight, and demi-culverings of the same length averaged in weight about 35 cwt. Iron falconetts are mentioned 4 feet in length, and weighing from 300 to 312 lbs.

The King, having occasion to send a present to the Emperor of Morocco, not an unfrequent occurrence, selected on one occasion four iron demi-culverings, and three brass demi-cannon of 8½ feet long, with one brass culvering of 11½ feet. A more frequent present to that monarch was gunpowder, or a quantity of muskets.

The salutes in the Tower were fired from culverings and 8-pounders, and were in a very special manner under the command of the Master-General himself. As little liberty of thought was left to the subordinates at the Tower as possible. Warnings of preparation were forwarded often days before, followed at intervals by reminders that the salute was not to be fired until a positive order should reach the Tower from the Master-General.

The letter-books at the Tower teem with correspondence and orders on this subject, and the Master-General seemed to write as many letters to his loving friends at the Tower about a birthday salute, about which no mistake could well occur, as he did about a salute of another kind, albeit a birthday one, when on the 10th June, 1688, "it pleased Almighty God, about ten o'clock of the morning, to bless his Majesty and his Royal Consort, the Queen, with the birth of a hopefull son, and his Majesty's kingdom and dominions with a Prince: for which inestimable blessing" public rejoicing was invited. It was a false tale which the guns rang out from the Tower: – only a few months, and the hopeful babe was a fugitive with its ill-fated father, and remained an exile for his life.

"He was indeed the most unfortunate of Princes, destined to seventy-seven years of exile and wandering, of vain projects, of honours more galling than insults, and hopes such as make the heart sick."6

At this time, Woolwich was gradually increasing in importance as an Artillery Depôt, and in 1672 the beginning of the Laboratory was laid, 70 feet long, "for receiving fireworks."

In 1682 Lord Dartmouth was appointed Master-General, and from this date until the Revolution the student of the Ordnance MSS. recognizes the existence of a master-spirit, and a clear-headed man of business. In 1683 he obtained authority from the King to reorganize the whole department, and define the duties of every official – a task which he performed so well that his work remained as the standard rule for the Board until it ceased to exist. His physical activity was as great as his mental: not a garrison in the kingdom was safe from his personal inspection; and the results of his examination were so eminently unsatisfactory as to call forth orders which, while calculated to prevent, had the effect also of revealing to posterity abuses of the grossest description. Not merely was neglect discovered among the storekeepers and gunners of the various garrisons – not merely ignorance and incapacity – but it was ascertained to be not unusual for a Master-Gunner to omit reporting the death of his subordinates, while continuing however to draw their pay. Lord Dartmouth's measures comprised the weeding out of the incapable gunners; the issue of stern warnings to all; the bringing the Storekeepers (who had hitherto held their appointments by letters patent from the Exchequer) under the immediate jurisdiction of the Board of Ordnance; the increase of the more educated element among the few Artillerymen on the permanent establishment, by the appointment of Gentlemen of the Ordnance, "lest the ready effects of our Artillery in any respect may perhaps be wanting when occasion shall be offered;" the appointment of Engineers to superintend the fortifications, with salaries of 100l. a year, under a Chief Engineer, Sir Bernard de Gomme; the encouragement of foreign travel and study; and the creation of discipline among the gunners at the Tower. Among the various causes of regret which affected Lord Dartmouth after the Revolution, probably none were more felt than the sorrow that he had been unable to complete the reformation in the Ordnance which he had so thoroughly and ably commenced.

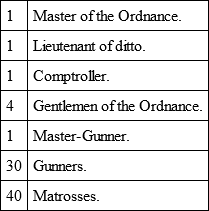

As a specimen of a train of Lord Dartmouth's time may be taken the one ordered to march on 21st June, 1685, to join Lord Feversham's force at Chippenham, and to proceed against the rebels. It consisted of

The guns used were brass Falcons and iron 3-pounders.

On examining the comparative pay of the various ranks, the Provost-Marshal seems to be well paid, ranking as he does in that respect with the Surgeon, and the Captain of the Pioneers. But if we may judge of the discipline of his train from one incident which has survived, his office can have been no sinecure. We find on the 23rd December, 1685, the King and Privy Council assembled at Whitehall, discussing gravely some conduct of certain members of the train, which had formed matter of complaint and petition from his Majesty's lieges. Four unhappy farmers had had a yoke of oxen pressed from each – the day after the rebels had been defeated – to bring off the carriages of the King's train of Artillery (then immovable, as might have been expected), and the animals had been made to travel as far as Devizes, forty miles from their home. One of the farmers, William Pope by name, had accompanied the train, in order that he might bring the oxen back. On applying for them at the end of the journey, the conductor "did abuse William Pope, one of the petitioners, by threatening to hang him for a rebel, as in the petition is more at large set forth." So the farmers now prayed to have their oxen, with the yokes and furniture, or their value, restored to them.

As the King in Council was graciously pleased to refer the complaint to Lord Dartmouth, with a view to justice being done, the reader need not doubt that the petitioners went away satisfied.

The details, contained in the Ordnance books, of the camp ordered by the King in 1686 to be formed at Hounslow, give the first intimation of that distribution of the Artillery of an Army, known as Battalion guns, a system which lasted in principle until 1871, although the guns ceased to be subdivided in such small divisions a good many years before. As, however, until 1871, the batteries had to accommodate themselves to the movements of the battalions near them, it may be said with truth that until then they were really Battalion guns. James II. ordered fourteen regiments to encamp at Hounslow with a view to overawing the disaffected part of the populace; but the effect was to reveal instead the unmistakable sympathy which existed between the troops and the people; so the camp was abruptly broken up. The Battalion guns were brass 3-pounders, under Gentlemen of the Ordnance, with a few other attendants, and escorted to their places by the Grenadiers of the various Regiments. Two demi-culverins of 10 feet in length, and six small mortar pieces, were also sent from the Tower to the camp.

In 1687, uneasiness was felt about Ireland, and large quantities of stores were assembled at Chester, for ready transit to that country if required. A large issue of mortars for that service was also made, the calibres being 14¼, 10, and 7 inches, and the diameters of the shells being respectively a quarter of an inch less. Among other guns which occur by name in the Ordnance lists of this year, and which have not yet been mentioned, are culverin drakes of 8 feet in length; saker-drakes of the same; and saker square guns also 8 feet long.

In the spring of 1688, his fatal year, King James was advised by Lord Dartmouth to send a young Gentleman of the Ordnance to Hungary to the Emperor's camp to improve himself in the art military, "to observe and take notice of their method of marching, encamping, embattling, exercising, ordering their trains of Artillery, their manner of approaching, besieging, or attacking any town, their mines, Batteries, lines of circumvallation and contravallation, their way of fortification, their foundries, instruments of war, engines, and what else may occur observable; and for his encouragement herein he was allowed the salary of 1l. per diem, besides such advance as was considered reasonable."

A long and difficult lesson was this which Richard Burton had to learn, and ere it should be mastered the Sovereign who encouraged him should be gone from Whitehall.

It was on the 15th of October, 1688, that undoubted advice reached the King that "a great and sudden invasion, with "an armed force of foreigners, was about to be made, in a hostile manner, upon his kingdom;" and although it is not contemplated to describe the campaigns of the pre-regimental days, a description of the train of Artillery with which he proposed to meet the invasion, and which was prepared for the purpose, cannot fail to be interesting. It is the most largely officered train which we have as yet met; and it was announced that, should the King accompany it at any time himself, it should be further increased by the presence of the Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, the Comptroller-General, the Principal Engineer, the Master-Gunner of England and his Clerks, the Chief Firemaster and his Mate, the Keepers and Makers of the Royal Tents and their Assistants. Exclusive of these, whose presence was conditional, the following was the personnel of