полная версия

полная версияStudies in the Theory of Descent, Volume II

“We are thus compelled to seek another possibility in mimicry, by which foes would be deceived by deceptive resemblance. But what is the object imitated? Dead insects overgrown by fungi are often found on leaves, the whitish or yellowish fungi growing from their bodies in various fantastic forms. Such insects of course no longer serve as tempting morsels. The processes of the pupa of Eueides suggest such fungoid growths, although I certainly cannot assert that to our eyes in broad daylight the resemblance is very striking. But the pupæ hang among the shadows of the leaves, and a less perfect imitation may deceive foes that are not so sharp-sighted; protective resemblance must commence moreover with an imperfect degree of imitation.”

EXPLANATION OF THE PLATES

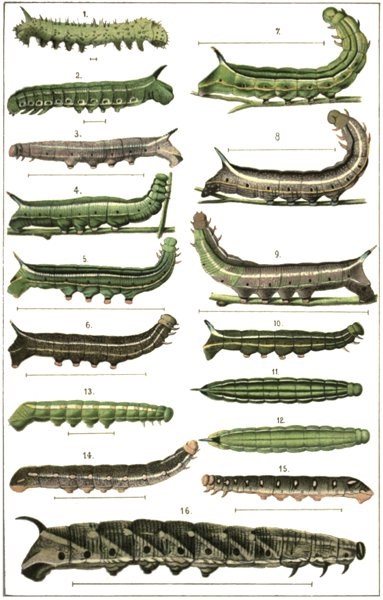

Plate IIIFigs. 1–12 represent larvæ of Macroglossa Stellatarum, all bred from one batch of eggs. Most of the figures are enlarged, but sometimes to a very small extent only; the lines show the natural length.

Fig. 1. Stage I.; a caterpillar immediately after hatching. Natural length, 0.2 centim.

Fig. 2. Stage II.; shortly after the first moult. Natural length, 0.7 centim.

Figs. 3–12. Stage V.; the chief colour-varieties.

Fig. 3. The only lilac-coloured specimen in the whole brood. Natural length, 3.8 centim.

Fig. 4. Light-green form (rare) with subdorsal shading off beneath.

Fig. 5. Green form (rare) with strongly-pronounced dark markings (dorsal and subdorsal lines). Natural length, 4.9 centim.

Fig. 6. Dark-brown form (common). Natural length, 4 centim. In this figure the fine shagreening of the skin is indicated by white dots; in the other figures these are partially or entirely omitted, being represented only in Figs. 8 and 10.

Fig. 7. Light-green form (common). Natural length, 4 centim.

Fig. 8. Light-brown form (common). Natural length, 3.5 centim.

Plate III.

Aug. Weismann pinx.

Lith. J. A. Hofmann, Würzburg.

Plate IV.

Aug. Weismann pinx.

Lith. J. A. Hofmann, Würzburg.

Plate V.

Aug. Weismann pinx.

Lith. J. A. Hofmann, Würzburg.

Plate VI.

Aug. Weismann pinx.

Lith. J. A. Hofmann, Würzburg.

Fig. 9. Parti-coloured specimen, the only one out of the whole brood. Natural length, 5.5 centim.

Fig. 10. Grey-brown form (rare).

Fig. 11. One of the forms intermediate between the dark-brown and green varieties, dorsal aspect.

Fig. 12. Light-green form with very feeble dorsal line (shown too strongly in the figure), dorsal aspect.

Figs. 13–15. Deilephila Vespertilio.

Fig. 13. Stage III.(?); the subdorsal bearing yellow spots. Natural length, 1.5 centim.

Fig. 14. Stage IV.; the subdorsal interrupted throughout by complete ring-spots, the white “mirrors” of which are bordered with black, and contain in their centres a reddish nucleus. Natural length, 3 centim.

Fig. 15. Stage V.; shortly after the fourth moult. Subdorsal line completely vanished; ring-spots somewhat irregular, with broad black borders; natural length, 3.5 centim.

Fig. 16. Sphinx Convolvuli, Stage V., brown form. Subdorsal line retained on segments 1–3, on the other segments present only in small remnants; at the points where the (imaginary) subdorsal crosses the oblique stripes there are large bright spots; natural length, 7.8 centim.

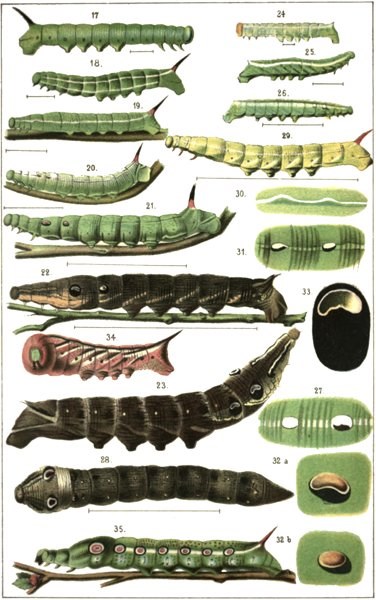

Plate IVFigs. 17–22. Development of the markings in Chærocampa Elpenor.

Fig. 17. Stage I.; larva one day after hatching. Natural length, 7.5 millim.

Fig. 18. Stage II.; larva after first moult. Length, 9 millim.

Fig. 19. Stage II.; immediately before the second moult (Fig. 30 belongs here). Length, 13 millim.

Fig. 20. Stage III.; after second moult. Length, 20 millim.

Fig. 21. Stage IV.; after third moult (Figs. 32 and 33 belong here). Length, 4 centim.

Fig. 22. Stage V.; after fourth moult. A feeble indication of an eye-spot can be seen on the third segment besides those on the fourth and fifth. Ocelli absent on segments 6–10.

Fig. 23. Stage VI.; after fifth moult. The subdorsal line is feebly present on segments 6–10, and very distinctly on segments 11 and 1–3. Ocelli repeated as irregular black spots above and below the subdorsal line on segments 6–11; a small light spot near the posterior border of segments 5–10 (dorsal spots) and higher than the subdorsal line. Larva adult.

Figs. 24–28. Development of the markings of Chærocampa Porcellus.

Fig. 24. Stage I.; immediately after emergence from the egg. Length, 3.5 millim.

Fig. 25. Stage II.; after first moult. Length, 10 millim.

Fig. 26. Stage III.; after second moult. Length, 2.6 centim.

Fig. 27. Eye-spots at this last stage; subdorsal much faded, especially on segment 4. Position the same as in last Fig.; magnified.

Fig. 28. Stage IV.; after third moult; corresponds exactly with Stage VI. of C. Elpenor. Dorsal view, with front segments partly retracted (attitude of alarm). Ocelli on segment 5 less developed than in Elpenor; repetitions of ocelli as diffused black spots on all the following segments to the 11th; two light spots on each segment from the 5th to the 11th, exactly as in Elpenor; subdorsal line visible only on segments 1–3. Length, 4.3 centim.

Fig. 29. Chærocampa Syriaca. From a blown specimen in Lederer’s collection, now in the possession of Dr. Staudinger. Length, 5.3 centim.

Fig. 30. First rudiments of the eye-spots of Chærocampa Elpenor, Stage II. (corresponding also with Fig. 19 in position, the head of the caterpillar being to the left). Subdorsal line slightly curved on segments 4 and 5.

Fig. 31. Eye-spots at Stage III. of the larva Fig. 20 somewhat further developed (larva immediately before third moult). Position as in Fig. 20.

Fig. 32. Eye-spots at Stage IV. corresponding to Fig. 21, A being the eye-spot of the fourth and B that of the fifth segment.

Fig. 33. Eye-spot at Stage V. of the larva of C. Elpenor; fourth segment.

Figs. 30–33 are free-hand drawings from magnified specimens.

Fig. 34. Darapsa Chærilus from N. America. Adult larva with front segments retracted. Copied from Abbot and Smith.

Fig. 35. Chærocampa Tersa, from N. America. Adult larva copied from Abbot and Smith.

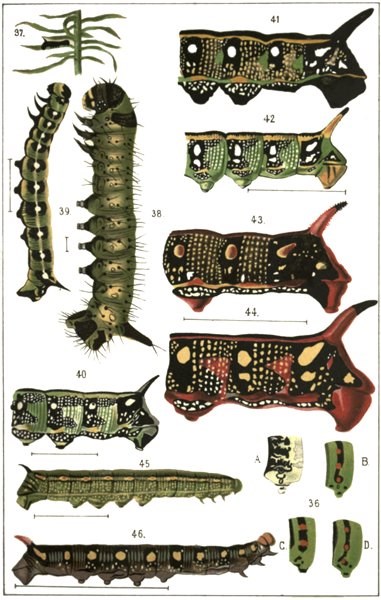

Plate VFig. 36. Sixth segment of adult Papilio-larvæ; A, P. Hospiton, Corsica; B, P. Alexanor, South France; C, P. Machaon, Germany; D, P. Zolicaon, California.

Figs. 37–44. Development of the markings of Deilephila Euphorbiæ.

Fig. 37. Stage I.; young caterpillar shortly after emergence. Natural length, 5 millim.

Fig. 38. Similar to the last, more strongly magnified. Natural length, 4 millim.

Fig. 39. Stage II.; larva immediately after first moult. The row of spots distinctly connected by a light stripe (residue of the subdorsal line). Natural length, 17 millim.

Fig. 40. Stage III.; after second moult; magnified drawing of the last five segments. Only one row of large white spots on a black ground (ring-spots); subdorsal completely vanished; the shagreen-dots formerly absent now appear in vertical rows interrupted only by the ring-spots. Below the latter are some enlarged shagreen-dots which subsequently become the second ring-spots. Natural length of the entire caterpillar, 21 millim.

Fig. 41. Stage IV.; the same larva after the third moult. Transformation of the ground-colour from green to black, owing to the spread of the black patches proceeding from the ring-spots in Fig. 40 in such a manner as to leave between them only a narrow green triangle. The shagreen dots below the ring-spots have increased in size, but have not yet coalesced.

Fig. 42. Stage III.; larva, same age as Fig. 40, but with two rows of ring-spots. Natural length of the whole caterpillar, 32 millim.

Fig. 43. Stage V.; larva from Kaiserstuhl. Variety with only one row of ring-spots, and with red nuclei in the mirror-spots. Natural length, 5 centim.

Fig. 44. Stage V.; larva from Kaiserstuhl (like the three preceding). The green triangles on the posterior edges of the segments in Fig. 42 have become changed into red. Natural length, 7.5 centim.

Fig. 45. Deilephila Galii; Stage IV. Subdorsal with open ring-spots. Natural length, 3.4 centim.

Fig. 46. D. Galii; adult larva; Stage V. Brown variety with feeble shagreening; subdorsal completely vanished. Natural length, 6 centim.

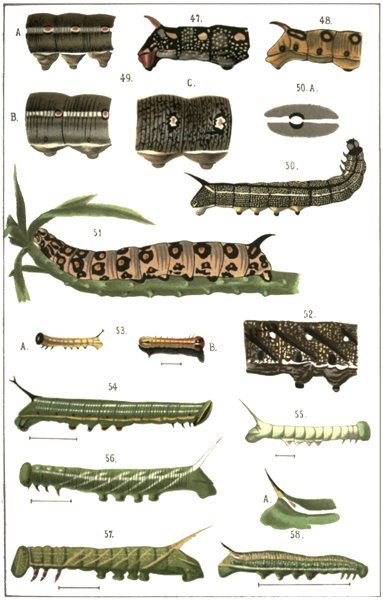

Plate VIFig. 47. The same species at the same stage. Black variety strongly shagreened; similar to Deil. Euphorbiæ.

Fig. 48. Similar to the last. Yellow var. without any trace of shagreening.

Fig. 49. Deilephila Vespertilio. Three stages in the life of the species, representing three phyletic stages of the genus. A, life-stage III.=phyletic stage 3 (subdorsal with open ring-spots); B, life-stage IV.=phyletic stage 4 (subdorsal with closed ring-spots); C, life-stage V.=phyletic stage 5 (subdorsal vanished, only one row of ring-spots).

Fig. 50. Deilephila Zygophylli, from S. Russia; stage V. From a blown specimen in Staudinger’s collection. In this specimen the ring-spots are difficult to distinguish on account of the extremely dark ground-colour; they are nevertheless present, and would probably be more distinct in the living insect. A, open ring-spot from another specimen of this species in the same collection.

Fig. 51. Deilephila Nicæa, from South France; Stage V. Copied from Duponchel.

Fig. 52. Sphinx Convolvuli; Stage V., segments 10–8. Brown variety, with distinct white spots at the points of intercrossing of the vanished subdorsal with the oblique stripes.

Fig. 53. Anceyrx Pinastri; A and B, larvæ immediately after hatching. Natural length, 6 millim.

Fig. 54. Same species; Stage II. Subdorsal, supra- and infra-spiracular lines developed. Natural length, 15 millim.

Fig. 55. Smerinthus Populi; Stage I. Immediately after hatching; free from all marking. Length, 6 millim.

Fig. 56. Same species at the end of first stage; lateral aspect. Length, 1.3 centim.

Fig. 57. Same species; Stage II. Subdorsal indistinct; the first and last oblique stripes more pronounced than the others. Length, 1.4 centim.

Fig. 58. Deilephila Hippophaës; Stage III. Subdorsal with open ring-spot on the 11th segment. A, segment 11 somewhat enlarged. Length, 3 centim.

Plate VIIFig. 59. Deilephila Hippophaës; Stage V. Secondary ring-spots on six segments (10–5).

Fig. 60. Same species; Stage V. One or two red shagreen dots on segments 10–4 in the position of the ring-spots of Fig. 59. Length, 6.5 centim.

Fig. 61. Same species; Stage V. Segments 9–6 of another specimen, more strongly magnified. A ring-spot on segments 9 and 8 showing its origin from two shagreen-dots; two red shagreen-dots on segment 7, on segment 6 only one.

Fig. 62. Deilephila Livornica (Europe) in the last stage. Green form. Copied from Boisduval.

Fig. 63. Pterogon Œnotheræ; Stage IV. Length, 3.7 centim.

Fig. 64. The same species at the same stage; dorsal view of the last segment.

Fig. 65. The same segment in Stage V. Eye-spot completely developed.

Fig. 66. Saturnia Carpini, larva from Freiburg; Stage III. Natural length, 15 millim.

Fig. 67. Same species; larva from Genoa; Stage IV. Length, 20 millim.

Fig. 68. Same species; larva from Freiburg; Stage III. Segments 8 and 9 in dorsal aspect. Length, 15 millim.

Fig. 69. The same caterpillar; lateral view of segment 8.

Fig. 70. Smerinthus Ocellatus; adult larva with distinct subdorsal on the six foremost segments. The shagreening is only shown in the contour, elsewhere omitted. Length, 7 centim.

Plate VII.

Aug. Weismann pinx.

Lith. J. A. Hofmann, Würzburg.

Plate VIII.

Aug. Weismann pinx.

Lith. J. A. Hofmann, Würzburg.

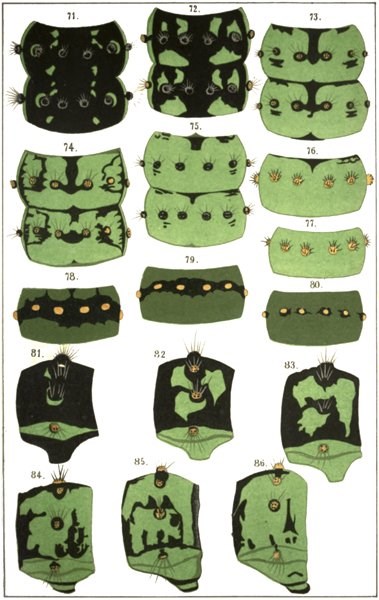

Plate VIII

Figs. 71–75 represent segments 8 and 9 of the larva of Saturnia Carpini (German form) in dorsal aspect, all at the fourth stage. The head of the caterpillar is supposed to be above, so that the top segment is the eighth.

Fig. 71. Saturnia Carpini. Darkest variety.

Fig. 72. Lighter variety.

Fig. 73. Still lighter variety.

Fig. 74. One of the lightest varieties; the black extends further on segments 9 and 10 than on the 8th.

Fig. 75. Lightest variety.

Figs. 76–80 are only represented on a smaller scale than the remaining Figs. in order to save space; were they enlarged to the same scale they would be larger than the other figures.

Fig. 76. Saturnia Carpini (Ligurian form); Segment 8; Stage V.

Fig. 77. Same form; same segment in stage VI.

Figs. 78, 79, and 80. Saturnia Carpini (German form); dorsal aspect of 8th segment in Stage V. (the last of this form).

Fig. 78. Darkest variety.

Fig. 79. Lighter variety.

Fig. 80. Lightest variety.

Figs. 81–86. Saturnia Carpini (German form); Stage IV. Side view of the 8th segment in six different varieties. Fig. 81 shows only two small green spots at the bases of the upper warts besides the green spiracular stripes. Fig. 82 shows the spots enlarged and increased by a third behind the warts; the pro-legs have also become green.

Fig. 83. Two of the three green spots, which have become still more enlarged, are coalescent.

Fig. 84. All three spots coalescent; but here, as also in

Fig. 85, various residues of the original black colour are left as boundary-marks.

Fig. 86. Lightest variety.

END OF PART IIPart III. ON THE FINAL CAUSES OF TRANSFORMATION

III. THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE MEXICAN AXOLOTL INTO AMBLYSTOMA

INTRODUCTION

Since the time when Duméril made known the transformation of a number of Axolotls into the so-called Amblystoma form, this Mexican Amphibian has been bred in many European aquaria, chiefly with the view to establish the conditions under which this transformation occurred, so as to be enabled to draw further conclusions as to the true causes of this exceptional and enigmatical metamorphosis.

Although the Amphibians propagated freely, the cases in which transformation occurred remained extremely rare, and it was not once possible to reply to the main question, viz. whether this metamorphosis was determined by external conditions or by purely internal causes; to say nothing of the possibility of there perhaps being discoverable certain definite external influences by means of which the metamorphosis could have been induced with certainty. But while these points are undecided all attempted theoretical interpretations of the phenomenon must be devoid of a solid basis.

It appeared to me from the first that the history of this transformation of the Axolotl was of special theoretical value; indeed I believed that it might possibly furnish a special case for deciding the truth of those ground-principles, according to which the origin of this species is represented by the two conflicting schools as a case of transformation or as one of heterogenesis. I therefore determined to make some experiments with the Axolotl myself, in the hopes of being fortunate enough to be able to throw some light upon the subject.

In the year 1872 Prof. v. Kölliker was so good as to leave with me five specimens of his Axolotls, bred in Würzburg, and these furnished a numerous progeny in the following year. With these I carried out the idea, the theoretical bearing of which will be shown subsequently, whether it would not be possible to force all the larvæ, or at any rate, the greater majority, to undergo transformation by exposing them to conditions of life which made the use of gills difficult, and that of lungs more easy; in other words, by compelling them to live partly on land at a certain stage of life.

During that year indeed I obtained no results, most of the larvæ perishing before the time for such an experiment had arrived, and the few survivors did not undergo transformation, but lived on to the following spring and then also died one after the other. Through long absence from Freiburg, necessitated by other labours, I had evidently left them without sufficient care and attention. I was thus led to the conviction, which was more fully confirmed subsequently, that no results can be obtained without the greatest care and attention in rearing, towards which single object all one’s interest should be concentrated, and it must not be considered irksome to have to devote daily for many months a large amount of time to this experiment. As it was evident that I could not afford this time without calling in other aid, I hailed with pleasure an opportunity of witnessing the experiment performed by other hands.

A lady living here (Freiburg), Fräulein v. Chauvin, undertook to rear a number of my larvæ of the following year which had just hatched, and in accordance with my idea to make the experiment of forcibly compelling them to adopt the Amblystoma form. How completely this was accomplished will be seen from the following notes by the lady herself, and it will no less appear that these results were only obtained by that care in treatment and delicacy of observation which she devoted to the experiments.

EXPERIMENTS

“I began the experiments on June 12th, 1874, with five larvæ about eight days old, these being the only survivors out of twelve. Owing to the extraordinary delicacy of these creatures, the quality and temperature of the water, and the nature and quantity of their food exerts the greatest influence, especially in early life, and one cannot be too cautious in their treatment.

“The specimens were kept in a glass globe of about thirty centimeters in diameter, the temperature of the water being regulated; as food at first Daphnids, and afterwards larger aquatic animals were introduced in large numbers. By this means all the five larvæ throve excellently. At the end of June the rudiments of the front legs appeared in the most vigorous specimens, and on the 9th of July the hind legs also became visible. At the end of November I noticed that one Axolotl remained constantly at the surface of the water, and this led me to suppose that the right period had now arrived for effecting the transformation into Amblystoma. For brevity I shall designate this as No. I., and the succeeding specimens by corresponding Roman numerals.

“In order to bring about this metamorphosis, on December 1st, 1874, No. I. was placed in a large-sized glass vessel containing earth arranged in such a manner that, when the vessel was filled with water, only one portion of the surface of the earth was entirely covered by the liquid, and the creature in the course of its frequent perigrinations was thus more or less exposed to the air. The water was gradually diminished on the following days, during which period the first changes made their appearance in the Amphibian —the gills commenced to shrivel up, and at the same time the creature showed a tendency to seek the shallowest spots. On December 4th, it took entirely to the land, and concealed itself among some damp moss which I had placed on a heap of sand on the highest portion of the earth in the glass vessel. At this period the first ecdysis occurred. Within the four days from the 1st to the 4th of December, a striking change took place in the external appearance of No. I., the gill-tufts shrivelled up almost entirely, the dorsal crest completely disappeared, and the tail, which had hitherto been broad, became rounded and similarly formed to that of a land salamander. The grey-brown colour of the body changed gradually into a blackish hue; isolated spots, at first of a dull white, made their appearance and these in time increased in intensity.

“When the Axolotl left the water on December 4th the gill-clefts were still open, but these closed gradually, and after about eight days were overgrown with skin and no longer to be seen.

“Of the other larvæ three appeared at the end of November (i. e. at the same time when No. I. came to the surface of the water) to have kept pace in development with No. I., an indication that for these also the right period had arrived for accelerating the developmental processes. They were therefore submitted to the same treatment as No. I. No. II. became transformed at the same time and exactly in the same manner as the latter; its gill-tufts were complete when it was first placed in the shallow water, but after four days these had almost entirely disappeared; in the course of about ten days after it took to the land, the overgrowth of skin on the gill-clefts and the complete assumption of the salamander form occurred. During this last period the creature took food, but only when urged to do so.

“In Nos. III. and IV. the development proceeded more slowly. Neither of these so frequently sought the shallow spots, nor did they as a rule remain so long exposed to the air, so that the greater part of January had expired before they took entirely to the land. Nevertheless the dessication of the gill-tufts did not take a longer time than in Nos. I. and II. as the first ecdysis occurred as soon as they took to the land.

“No. V. showed still more striking deviations in its transformation than Nos. III. and IV., but as this specimen appeared much weaker than the others from the beginning and was retarded in growth to a most notable extent, this is by no means surprising. It took fourteen instead of four days before the transformation had advanced far enough to enable it to leave the water. It was especially interesting to observe the behaviour of this specimen during this period. Its weak and delicate constitution evidently made it much more susceptible to all external influences than the others. If exposed to the air for too long a time it acquired a light colour, and when annoyed or alarmed it emitted a peculiar odour, similar to that of a salamander. As soon as these phenomena were observed it was at once placed in deeper water, into which it immediately plunged and gradually recovered itself, the gills always becoming again expanded. The same experiment was repeated several times and always led to the same result, from which we may venture to conclude that by accelerating the transformation too energetically, the process may come to a standstill, and even by continued compulsion may end in death.

“It yet remains to be mentioned with respect to Axolotl No. V. that this specimen, unlike all the others, did not emerge from the water at the first ecdysis, but at the time of the fourth.

“All the Axolotls are now (July, 1875) living, and are healthy and vigorous, so that with respect to their state of nourishment there is nothing to prevent their propagating. Of the first four the largest is fifteen centim. long; Axolotl No. V. measures twelve centim.

“The preceding statements appear to demonstrate the correctness of the views advanced in the Introduction: – Axolotl larvæ generally but not always complete their metamorphosis if, in the first place, they emerge sound from the egg and are properly fed; and if, in the next place, they are submitted to the necessary treatment for changing aquatic into aërial respiration. It is obvious that this treatment must only be applied very gradually, and in such a manner as not to overtax the vital energy of the Amphibian.”

* * * * *To the foregoing remarks of Fräulein v. Chauvin I may add that in all five cases the transformation was complete, and not to be confounded with that change which occurs more or less in all Axolotls in the course of time when confined in small glass vessels. In this last case there frequently appear changes in the direction of the Amblystoma form without the latter being actually reached. In the five adult Axolotls which I possessed for a short time, and of which two were at least four years old, the gills were much shrivelled, but the aquatic tail and dorsal crest were unchanged. The crest may, however, also disappear, and the tail become shortened without these changes being due to a transformation into Amblystoma, as will be shown further on.