Полная версия

Favourite Dog Stories: Shadow, Cool! and Born to Run

“Bamiyan,” I said. “She came to our home. It was months ago, nearly a year maybe.”

“Bamiyan?” The interpreter was amazed. They both were. “Sergeant Brodie says that is impossible,” said the Afghan soldier. “Bamiyan is hundreds of miles away, up north. This whole thing is impossible.”

As the interpreter was talking, the soldier seemed suddenly to be looking about him nervously. “Sergeant Brodie says we can’t stand here chatting out in the open,” the interpreter went on. “The Taliban could be watching us. They have eyes everywhere. They have ambushed us on this road before. But he has to find out more about all this, about you and Polly. We must go into the village, he says. We can be safer there.”

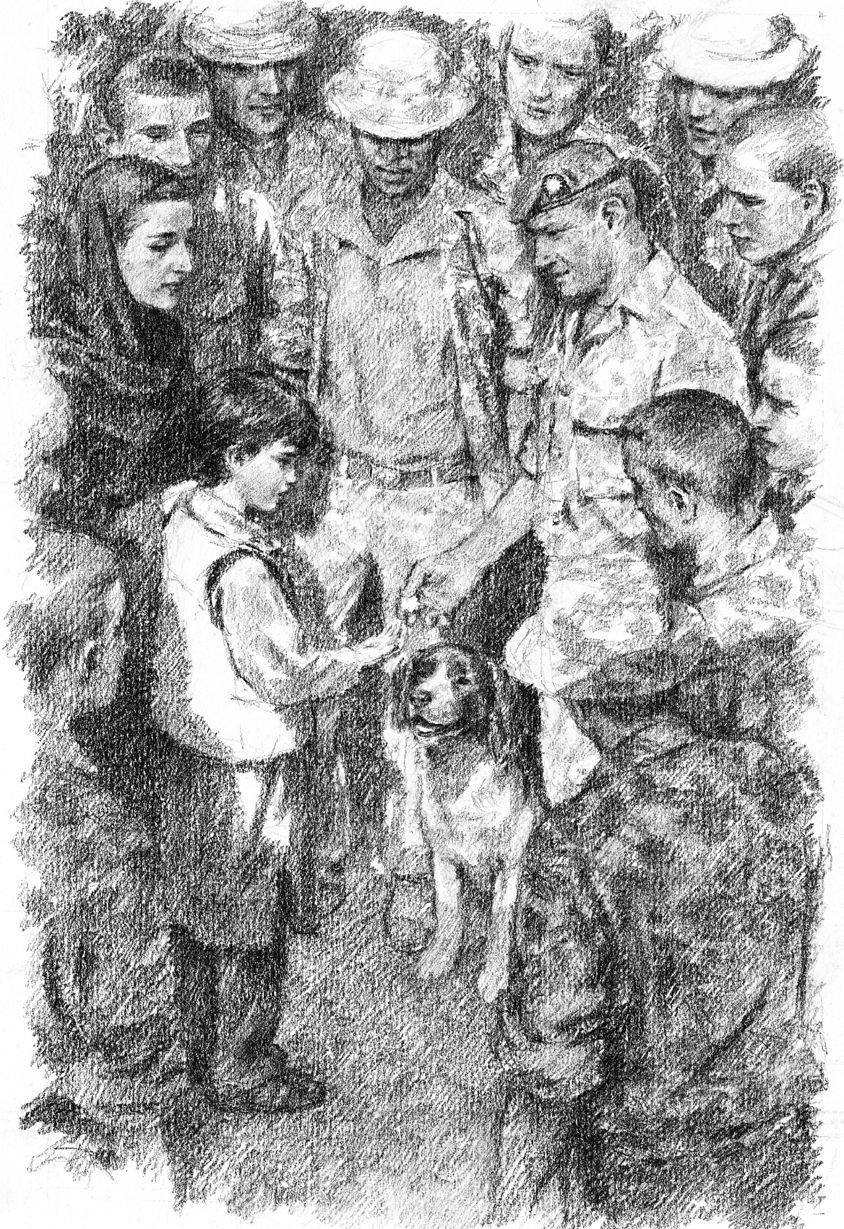

So with Sergeant Brodie holding my hand, the soldiers behind us, and Shadow running on ahead, showing us the way as usual, we walked back into the village, the village children all around us.

“Quite a Hero”

Aman

So that’s how we all found ourselves a few minutes later sitting inside a house in the village, changed into dry clothes the villagers had found for Mother and me, and sipping glasses of tea, with the whole room crowded with people, villagers and soldiers, the interpreter and this Sergeant Brodie, all of them listening, as I told them about how Shadow had wandered into our cave all those months before, more than a year ago, and how she’d been hurt in the leg somehow and was starving, how she’d got better, and that we were now on our way to England to live in Manchester, with my Uncle Mir, who had once shaken hands with David Beckham.

The soldiers laughed at that. It turned out that one or two of them supported Manchester United, and that David Beckham was their hero too. So I knew then I was amongst friends.

All this time Shadow lay beside me, her head on my feet, eyeing everyone in the room.

When I had finished, Sergeant Brodie was the first to say anything. He spoke through his interpreter again.

“The sergeant says he’s got something to tell you about this dog,” he began. The interpreter spoke Dari with an accent I wasn’t used to, but Mother and I understood enough. “He says you’re going to find it difficult to believe this. He finds it difficult to believe it himself, but it really is true. He’s asked all the soldiers who were here a year or so ago, and they all agree. There is no doubt about it. We all know this dog. That dog, she is called Polly, and she’s sniffed out more roadside bombs – the army calls them IEDs, Improvised Explosive Devices – than any other dog in the whole army. Seventy-five. Today was the seventy-sixth. And that dog disappeared, the sergeant says, about fourteen months ago now. He was there when it happened. And so was I.

“We were out on patrol, just like today. Sergeant Brodie was with us on that patrol too. He was Polly’s handler. Polly lived with him and his family when they were back home in England. The sergeant was the one who trained her up, looked after her and lived with her on the base. The best sniffer dog he’d ever known, he says. Everyone said so. Anyway, there we were, out on patrol, Sergeant Brodie and Polly going on ahead of us, checking the roadsides for bombs as usual. When we saw Polly was on to something, we all stopped. And that’s when the Taliban ambushed us.

“The fire-fight that followed went on for an hour or so, and when it was over we found we had one man wounded, Corporal Banford it was, and Polly wasn’t there. She was nowhere to be seen. She had disappeared. We called her and we called her, but we couldn’t hang about looking for her. It was too dangerous.

“We brought in a helicopter to get Corporal Banford out of there, and off to hospital as quick as we could. Sadly, it wasn’t quick enough. He died on the way to hospital. We came back to look for Polly the next day, and told every patrol that went out after that to keep an eye out for her. But no one ever saw her again. So we all thought she’d been killed. We’d lost two soldiers that day. That’s how we thought of her, as one of us.”

The interpreter had to wait a few moments for the sergeant to begin again.

“Sergeant Brodie is saying,” he went on, “that the Taliban target our sniffer dogs if they can – they know how valuable they are to us, how many soldiers’ lives they save. That’s what he thought had happened to her. That’s what everyone thought. We put up a little memorial for her back at the base. Then, we come out here today, fourteen months later, and there you are waving us down to warn us, and there she is sniffing out a bomb just like she was when we last saw her. It’s incredible. And if I’ve understood it right, that dog wandered hundreds of miles north before she found you in Bamiyan, and then hundreds of miles back. I know it sounds silly, but I reckon she knew where she was going. She had to find someone to look after her, and that was you, and then she knew she had to come back where she belonged. Somehow she must have known the way home, sort of like a swallow does.”

When he told me that last bit about Shadow knowing the way home, I was sure he had to be right. Wherever we had been since we left Bamiyan, Shadow always seemed to know the way to go. It was us, Mother and me, who had followed her, not the other way around. And so much else was making sense to me now, how Shadow was always running on ahead of us, nose to the ground, sniffing the roadside. This was what she’d been trained to do. She was an army sniffer dog, just like that driver in the lorry had told us.

“Believe me, when they hear about this back at base,” the interpreter said, “the sergeant says you are going to be quite a hero for our lads. After all, it was you who warned us about the bomb. And it was you who rescued Polly, looked after her, and brought her back to us. They are going to be ‘over the moon’, as they say in English – and so is his daughter back home in England. She loved that dog to bits. The whole family did, the sergeant himself most of all. Yes, you’re going to be quite a hero.”

Silver, Like a Star

Aman

As we set off again, Sergeant Brodie saw that I was limping, and Mother told him through the interpreter about my bad foot. So I got a lift, a piggy-back ride on Sergeant Brodie’s back, all the way to the base. No one had done that for me since Father died. It felt so good.

And the sergeant was right. At the base, they did make a real fuss of me, of all of us, particularly Shadow. Nothing was too much trouble. We slept in a warm bed, ate all we wanted, had a shower whenever we liked. And they had a doctor there too who had a look at my blister. She said it was infected, that I’d have to stay on the base for a while, and not walk on it, not until it had healed up. They even let Mother telephone Uncle Mir in England.

So Mother and Shadow and me, we stayed there on the base – it must have been for nearly a week, I think. They gave us a little room of our own and Mother slept a lot, and when my foot was better I played football with the soldiers.

That was when I first learned to play Monopoly too. It was Sergeant Brodie who taught me. I learned to say my first words in English, and he learned some Dari too. Sergeant Brodie and me and Shadow, we’d spend a lot of time together, when he wasn’t busy, when he wasn’t out on patrol. Like all the other soldiers, he kept wanting to take photos of Shadow and me to send home on his phone.

Once, he showed me a live video of his daughter and his wife, taken on their phone. They were waving at me all the way from England, and shouting thank you to me for saving Polly. I should have been happy, but I wasn’t. There was something that was troubling me. And it was troubling Shadow too, I could tell.

I knew by now we’d have to be leaving soon, as soon as my heel was better, and somehow she seemed to know it too. As the days went by Shadow wanted more and more to stay with us. But I could see she loved being with the soldiers too, particularly with Sergeant Brodie. He had even kept her favourite ball to remember her, the one she’d always liked to play with. The soldiers would throw it for her, and she’d chase it right across the compound, bringing it back, but not letting it go, till she was given something to eat in return.

But she never played with them for too long. Always she came back to sit near me, and I’d catch her looking at me, and we’d both know what it was we were thinking. Is she Polly? Is she Shadow? Would she be coming with us when we left?

I knew the answer. She knew the answer. I think we both kept hoping that both of us were wrong. I could feel she was becoming theirs again, an army dog, Sergeant Brodie’s dog. Polly, not Shadow. She still slept with us in our room, often came to lie down beside me with her head on my foot. I still hoped she would be coming with us, but I knew already deep down that it wasn’t going to happen, that she would be staying on the base with the soldiers, that she was back with Sergeant Brodie where she belonged.

She knew it too, and was as sad about it as I was, and as Mother was too – she often told me later that she could never have imagined that she could become so fond of a dog.

I think all the soldiers could see my sadness. The soldiers may have been exhausted when they came back into the base after a patrol, with their rifles and their helmets, but they always had a smile for me. They all knew by now why we were on the road, what we were running away from, all about how Mother had been treated by the police, about how Grandmother had died.

Sergeant Brodie came in to see us on the evening before we left, with the interpreter, who told us that the soldiers had collected some money to help us on our way, a whip-round, he called it. I think I knew what was coming next from the sad expression on his face. He said it all through the interpreter. He could hardly look at me.

“About Polly. I’m sorry, Aman, but she has to stay here. She’s an army dog. Maybe you can come and see her again, when you get to England, I mean. How’d that be?” He was only trying to soften the blow, I realised that. But who knew if we would ever even make it to England, without Shadow to lead us there?

I cried when he’d gone out. I couldn’t stop myself. Mother said it was for the best, that we’d be fine on our own from now on, God willing. And this time, she said, we were going to look after our money. That was why, with Shadow beside me on the bed, I spent most of our last night on the base hollowing out the heels of our shoes, the best place we could think to hide our money. Shadow watched me all the time. She knew for sure these would be our last few hours together.

I could hardly bear to look at her.

When we left the next morning, the soldiers were there to see us off, and so was Shadow. Sergeant Brodie called for three cheers, and when it was over he stepped forward to say goodbye to us. He pressed something into my hand. The interpreter was there to help him as usual. “Our regimental badge, Aman,” he was telling me. “The sergeant says you’ve earned it. He says he hopes you get to England all right. And when you do, and you ever need any help, let him know. He’ll be there. And if you want to see Polly again, just ask. You can always get in touch with him through the regiment. And he says to thank you, for bringing Polly back to him, for saving the lives of his men, that he’ll never forget what you did for us, for all the lads, for the regiment.”

I crouched down to say my last goodbyes to Shadow, stroked the dome of her head, and ruffled her ears. But I couldn’t say anything. If I spoke, I knew I would cry, and I didn’t want to do that, not in front of the soldiers.

As they drove us off out of the base, I longed for Shadow to jump up and come with us. But I knew she wouldn’t, that she couldn’t.

That was the last I saw of her.

They drove us to the nearest town, and put us on a bus. I sat there clutching my badge. I looked down at it for the first time. It was silver, like a star, with what looked like a picture of castle walls on it. And there was some writing below that I couldn’t read then.

(It said Royal Anglian. I’ve still got it. I take it with me everywhere.)

We were on our way again, to England, to Uncle Mir and Manchester. Sitting there on the bus, I remember I tried hard to think of David Beckham, to stop me feeling so sad about leaving Shadow. But it didn’t work. Then I looked down at my star, and squeezed it tight. It made me feel better. That silver star always has, ever since.

“The Whole Story, I Need the Whole Story.”

Grandpa

All this time, as Aman was telling his story, he had hardly looked up at me. It seemed to me that as he was telling it, he needed to relive his memories without any kind of distraction. He spoke so softly that he could almost have been talking to himself, his voice often barely a whisper. Sometimes I had to lean right forward to hear what he was saying. But throughout it all, his voice had been steady, until the very last bit, the moment he’d had to leave Shadow behind. I could hear then that he was fighting back the tears.

When he got up suddenly and rushed out of the visiting room, I was sure it must be because he did not want me to see him crying. I knew too that he might not come back, that he might be too proud to have to face me again after that. But I waited there anyway, because somehow I felt there was at least a chance he would come back. After all, he’d come back before, hadn’t he?

Sitting alone at the table I wished more than anything that Matt could be with me. Aman wouldn’t have run off like that if Matt had been there. They were friends, best friends. Matt would have been able to talk him round somehow.

It was then, with Aman’s story still fresh in my head, that I first began to consider seriously whether there really might be something that could be done to help Aman and his mother – besides just visiting them, I mean.

The longer I sat there, and thought about the poverty of their lives in Bamiyan, of the suffering the whole family had lived through, of their determination to get out of Afghanistan and come to England, the more I hated to think of them locked up like criminals in this place. There was a terrible injustice going on here. Aman’s story had awoken the journalist in me. I wanted to know more.

I wanted to know everything.

When Aman did come back a few minutes later, his mother was with him again. I hadn’t expected this at all. There was so much I still had to find out about. I’d been hoping that when he came back, he would be able just to pick up his story where he’d left off. But I knew Aman was much more shy and reserved with his mother around, so I wasn’t at all hopeful he would talk as easily or as freely as he had before. I could see his mother had been crying, and was still very overwrought. She was rocking back and forth, clutching a handkerchief in both hands.

His mother spoke up then, but only to Aman, and in her own language. When she had finished, he translated for her. “Mother says she had to come and tell you herself that we cannot go back to Afghanistan, that the police would torture her again. She says the Taliban are not defeated, they are everywhere, in the police, everywhere. They will kill her, just like they killed Father. She says we have been living in England for six years now. This is our home. She says our lawyer cannot help us any more, that the government won’t even let us appeal. She has prayed to God that you will be able to help us. Her dream tells her you will, but she has come to ask you herself, to beg you to make her dream come true.”

I didn’t know what to say, only that I had to say something, and something encouraging too, but without making promises I could not keep.

“Tell her I can do my best, and I will,” I told him. “But she must understand, and so must you, Aman, that I am not a lawyer. I’m not sure what I can do, what anyone can do. But I do know that for me to be able to do anything at all, I will need you to tell me your whole story, from the time you left Shadow behind, and got on the bus that day, until now, until today. I mean, how did you manage to get all the way to England? How have you been living, and what exactly happened when they brought you in here? The more I know, the better. I need to know everything.”

Aman talked to his mother for a few moments, to explain things. She was calmer now, more composed. Then he turned back to me, took a deep breath, and began again, reluctantly though, almost as if he did not want to remind himself at all of the rest of the story, as if he was dreading having to live through it again.

“God is Good.”

Aman

All right, if you think it will help, I’ll go on then. The bus. We were on the bus. It was a comfortable bus, the most comfortable I’d ever been on. I was missing Shadow, of course I was; but apart from that, I was feeling really up. I think I imagined this bus would take us all the way to England. I was only eight then, remember. I hadn’t any real idea where England was, nor how far it was away, nor how long it would take us to get there.

I think if we had known what a long and terrible journey it was going to be, then I’d never have got on to that bus in the first place. As it turned out, that bus journey was the last time we were going to be comfortable, or happy, for a very long time.

Mother was sick with worry when we came to the frontier with Iran, I could see that. She told me we were going to play a game. If the soldiers came on board to check us, we had to pretend we were asleep. So that’s what we did. I heard them coming down the bus, but they passed by us without stopping. I only dared to open my eyes when the bus was on its way again. We were through.

“You see, Aman,” she whispered to me, “God is good. God is helping us.”

She told me then that she had telephoned from the army base to Uncle Mir’s contact in Teheran, the next big city, and he would be there waiting to meet us when we arrived, that he would take care of everything. So we had nothing more to worry about. I think I must have slept almost all the way, because I don’t remember much about that journey, only that it seemed endless.

Uncle Mir’s friend was there to meet us, as Mother had said. He walked us through the streets, warning us not to talk to anyone, and not to look anyone in the eye, particularly policemen. He told us that if we got caught they would put us in prison, or send us back to Afghanistan. So of course we did what he said. He took us first to one man, who took some money off Mother, then to another who Uncle Mir’s friend called ‘the fixer’, who took even more money off her.

I didn’t like any of these people. I didn’t trust them either. They treated us as if we were dirt. I felt lost in a strange and hostile world, with no Shadow to guide us any more. But I had my silver star. I kept it hidden in my pocket. I never took it out in case someone saw it. I’d squeeze on it tight whenever I was frightened, which was a lot of the time, and always before I went to sleep at night. It was my talisman, my lucky charm.

Uncle Mir’s friend kept telling us everything would be all right, that we would be looked after now all the way to England. Travel, food, we’d have everything we needed. There would be no problems, he said, no problems at all.

We believed him. We trusted him. We had to. We didn’t have a choice, did we? But it turned out to be the beginning of a nightmare. They took us down into a cellar, and said we’d have to stay there till everything was arranged. We were there for days on end. They gave us food and water, but they wouldn’t let us out, except to go to the toilet. Mother said it was like being back in the police cell in Afghanistan.

Then they came for us one night, took us out into a dark alleyway and shoved us into the back of a pick-up truck. I remember looking out of the back and seeing all the bright lights of the city. Once, when we were waiting at traffic lights, I said to Mother that we should climb out and make a run for it, that we were better off on our own. But then the truck moved off, and the chance to escape was gone.

We never had another one.

Somewhere on the edge of the city, the pick-up stopped. There were people waiting for us. They made us get out and climb up into the inside of a huge lorry. It looked empty at first, but it wasn’t. At the back, there was a large metal container, its doors wide open. They pushed us in, threw us a couple of blankets, told us we had to be quiet and just left us. It was pitch black in there, and cold. We sat huddled in the corner, Mother telling me all the time it was going to be all right, that Uncle Mir knew what he was doing, that these were good people who were looking after us, and that everything would turn out fine, God willing.

Hours later, when we heard the sound of voices outside, and when the lorry started up and moved off, I began to believe she was right, right about everything, that maybe the worst was over. I kept telling myself that we would soon be in England with Uncle Mir, and we would have a warm place to sleep, running water, television, and I could go to see Manchester United play and see David Beckham. I might even meet him.

But it wasn’t only those thoughts that kept me going, it was my silver star, and the memory I had in my head of Shadow, always trotting on ahead of us, her tail waving us on, how she’d stop to look back at us from time to time to make sure we were coming, her eyes telling us that all we had to do was to keep going like she did. I just had to think about her, picture her in my mind, and, however hungry or cold or frightened I was, it made me feel a little better, for a while, but not for long.

I was half asleep by the time the lorry stopped again. We heard footsteps from inside the lorry, then voices right outside our container. “Police,” Mother whispered. “It’s the police. They’ve found us. Please God, no. Please God, no.” She had her arms around me, holding me tight, kissing me and kissing me, as if it was for the last time.

The Little Red Train

Aman

The door of the container opened. The daylight blinded us. We could not see who it was at first.

It was not the police.

It turned out to be the fixer man, and his gang, the same people who had put us in there. They said we could get out if we wanted and stretch our legs, that we were waiting for some other people to join us.

We were in a kind of loading bay with lorries all around, but not many people. We should have run off there and then, but one of the fixer’s gang always seemed to be watching us, so we didn’t dare.

Only a few minutes later, it was too late.

The other refugees arrived, and we were all herded back into the same container, given some more blankets, a little fruit, and a bottle or two of water. They slammed the doors shut on us again and the fixer shouted at us, that no matter what, we mustn’t call out, or we’d all be caught and taken to prison. We could hear the lorry being loaded up around us.

It was a while, I remember, before my eyes became accustomed to the dark again, and I could see the others.

As the lorry drove off we sat there in silence for a while, just looking at one another. I counted twelve of us in all, mostly from Iran, and a family – mother, father and a little boy – from Pakistan, and beside us an old couple from Afghanistan, from Kabul.

It was Ahmed, the little boy from Pakistan, who got us talking. He came over to me to show me his toy train, because I was the only other kid there, because he knew he could trust me, I think – it was plastic and bright red, I remember, and he was very proud of it.

He knelt down to show me how it worked on the floor, telling everyone about how his grandpa worked on the trains in Pakistan. And, in secret, I showed him the silver-star badge Sergeant Brodie had given me. Ahmed loved looking at it. He was full of questions about it, about everything. He liked me, he said, because I had a name that sounded like his. It wasn’t long before we were all telling one another our stories. To begin with, Ahmed and me, we laughed a lot, and played about, and that cheered everyone up. But it didn’t last. I think our laughter lasted about as long as the fruit and water.