Полная версия

Favourite Dog Stories: Shadow, Cool! and Born to Run

Michael Morpurgo

Favourite Dog Stories:

Shadow, Cool! and Born to Run

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Shadow

Cool!

Born to Run

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Michael Morpurgo

Copyright

About the Publisher

For Juliet, Hugh, Gabriel, Ros and Tommo

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Preface

When the Stars Begin to Fall

“And They Keep Kids in There?”

We Want You Back

Shadow

Bamiyan

“Dirty Dog! Dirty Foreign Dog!”

“You Must Come to England.”

“Walk Tall, Aman.”

Somehow

Counting the Stars

Polly

“Quite a Hero”

Silver, Like a Star

“The Whole Story, I Need the Whole Story.”

“God is Good.”

The Little Red Train

All Brothers and Sisters Together

“It’s Where We Belong Now.”

Locked Up

“We’re Going To Do It!”

Shooting Stars

“Just Two of Them And a Dog.”

Singing in the Rain

Time To Go Home

Postscript

Introduction

So many have helped in the genesis of Shadow. First of all, Natasha Walter, Juliet Stevenson and all involved in the writing and performing of Motherland, the powerful and deeply disturbing play that first brought to my attention the plight of the asylum-seeking families locked up in Yarl’s Wood. Then there were two remarkable and unforgettable films, that inspired and informed the Afghan part of this story: The Boy who Plays on the Buddhas of Bamiyan, directed by Phil Grabsky, and Michael Winterbottom’s In This World. And my thanks also to Clare Morpurgo, Jane Feaver, Ann-Janine Murtagh, Nick Lake, Livia Firth, and so many others for all they have done.

Michael Morpurgo August 2010

Preface

This story has touched the lives of many people, and changed their lives too, for ever. It is told by three of these people: Matt, his grandfather and Aman. They were there. They lived it. So it’s best they tell it themselves, in their own words.

When the Stars Begin to Fall

Matt

None of it would ever have happened if it hadn’t been for Grandma’s tree. And that’s a fact. Ever since Grandma died – that was about three years ago now – Grandpa had always come to spend the summer holidays at home with us up in Manchester. But this summer he said he couldn’t come, because he was worried about Grandma’s tree.

We’d all planted that tree together, the whole family, in his garden in Cambridge. A cherry tree it was, because Grandma especially loved the white blossoms in the spring. Each of us had passed around the jug and poured a little water on it, to give it a good start.

“It’s one of the family now,” Grandpa had said, “and that’s how I’m going to look after it always, like family.”

That was why, a few weeks ago, when Mum rang up and asked him if he was coming to stay this summer, he said he couldn’t because of the drought. There had been no rain for a month, and he was worried Grandma’s tree would die. He couldn’t let that happen. He had to stay at home, he said, to water the tree. Mum did her best to persuade him. “Someone else could do that, surely,” she told him. It was no good. Then she let me have a try, to see if I could do any better.

That was when Grandpa said, “I can’t come to you, Matt, but you could come to me. Bring your Monopoly. Bring your bike. What about it?”

So that’s how I found myself on my first night at Grandpa’s house, sitting out in the garden with him beside Grandma’s tree, and looking up at the stars. We’d watered the tree, had supper, fed Dog, who was sitting at my feet, which I always love.

Dog is Grandpa’s little brown and white spaniel, with a permanently panting tongue. He dribbles a lot, but he’s lovely. It was me that named him Dog, apparently, because when I was very little, Grandpa and Grandma had a cat called Mog. The story goes that I chose the name because I liked the sound of Dog and Mog together. So he never got a proper name, poor Dog.

Anyway, Grandpa and me, we’d had our first game of Monopoly, which I’d won, and we’d talked and talked. But now, for a while, we were silent together, simply stargazing.

Grandpa started to hum, then to sing. “When the stars begin to fall… Can’t remember the rest,” he said. “It’s from a song Grandma used to love. I know she’s up there, Matt, right now, looking down on us. On nights like these the stars seem so close you could almost reach out and touch them.”

I could hear the tears in his voice. I didn’t know what to say, so I said nothing for a while. Then I remembered something. It was almost like an echo in my mind.

“Aman said that to me once,” I told him, “about the stars being so close, I mean. We were on a school trip down on a farm in Devon, and we snuck out at night-time, just the two of us, went for a midnight walk, and there were all these stars up there, zillions of them. We lay down in a field and just watched them. We saw Orion, the Plough, and the Milky Way that goes on for ever. He said he had never felt so free as he did at that moment. He told me then, that when he was little, when he first came to live in Manchester, he didn’t think we had stars in England at all. And it’s true, Grandpa, you can’t see them nearly so well at home in Manchester – on account of the street lights, I suppose. Back in Afghanistan they filled the whole sky, he said, and they felt so close, like a ceiling painted with stars.”

“Who’s Aman?” Grandpa asked me. I’d told him before about Aman – he’d even met him once or twice – but he was inclined to forget things these days.

“You know, Grandpa, my best friend,” I said. “We’re both fourteen. We were even born on the same day, April 22nd, me in Manchester, him in Afghanistan. But they’re sending him back, back to Afghanistan. He’s been to the house when you were there, I know he has.”

“I remember him now,” he said. “Short fellow, big smile. What do you mean, sending him back? Who is?”

So I told him again – I was sure I’d told him it all before – about how Aman had come into the country as an asylum seeker six years before, and how he couldn’t speak a word of English when he first came to school.

“He learned really fast too, Grandpa,” I said. “Aman and me, we were always in the same class in junior school and now at Belmont Academy. And you’re right, Grandpa, he is small. But he can run like the wind, and he plays football like a wizard. He never talks much about Afghanistan, always says it was another life, and not a life he wants to remember. So I don’t ask. But when Grandma died, I found that Aman was the only one I could talk to. Maybe because I knew he was the only one who would understand.”

“Good to have a friend like that,” said Grandpa.

“Anyway,” I went on, “he’s been in this prison place, him and his mum, for over three weeks now. I was there when they came and took him away, like he was a criminal or something. They’re keeping them locked up in there until they send them back to Afghanistan. We’ve written letters from school, to the Prime Minister, to the Queen, to all kinds of people, asking them to let Aman stay. They don’t even bother to write back. And I’ve written to Aman too, lots of times. He wrote back only once, just after he got there, saying that one of the worst things about being locked up in this prison place is that he can’t go out at night and look at the stars.”

“Prison place, what d’you mean, prison place?” Grandpa asked.

“Yarl’s— something or other,” I said, trying to picture the address I’d written to. “Yarl’s Wood, that’s it.’

“That’s near here, I know it is. Not far anyway,” said Grandpa. “Maybe you could visit him.”

“It’s no good. They don’t let kids in,” I said. “We asked. Mum rang up, and they said it wasn’t allowed. I was too young. And anyway, I don’t even know if he’s still in there. Like I said, he hasn’t written back for a while now.”

Grandpa and I didn’t talk for some time. We were just stargazing again, and that was when I first had the idea. Sometimes I think that’s where the idea must have come from. The stars.

“And They Keep Kids in There?”

Matt

I was worried about how Grandpa might react, but it was worth a try, I thought.

“Grandpa?” I said. “I’ve been thinking about Aman. I mean, maybe we could find out. Maybe you could ring up, or something, and see if he’s still there. And if he is, then you could go, Grandpa. You could go and see Aman instead of me, couldn’t you?”

“But I hardly know him, do I?” Grandpa replied. “What would I say?”

I could tell he didn’t much like the idea. So I didn’t push it. You couldn’t push Grandpa, everyone in the family knew that. As Mum often said, he could be a stubborn old cuss. So we sat there in silence, but all the time I knew he was thinking it over.

Grandpa said nothing more about it that night, nor at breakfast the next morning. I thought that either he’d forgotten all about it, or he’d already made up his mind he didn’t want to do it. Either way, I didn’t feel I could mention it again. And anyway, by now I think I had almost given up on the idea myself.

It was part of Grandpa’s daily routine, whatever the weather, to get up early and take Dog for a walk along the river meadows to Grantchester – his ‘constitutional’, he called it. And I know he always liked me to come with him when I was staying. I didn’t much like getting up early, but once I was out there, I loved the walks, especially on misty mornings like this one.

There was no one about, except a rowing boat or two, and ducks, lots of ducks. There were cows in the meadows, so I had to keep Dog on the lead. I was having a bit of a struggle hanging on to him. There was always some rabbit hole he just had to stay behind to investigate, or some molehill he insisted he must make friends with. He was pulling all the time.

“Funny coincidence though,” Grandpa said suddenly.

“What is?” I asked.

“That Yarl’s Wood place you were talking about last night. I think that could be the detention centre place Grandma used to visit, years ago, before she got ill. My memory’s not what it was, but I think it was called Yarl’s Wood – that’s probably how I knew about it. She was a sort of befriender there.”

“A befriender?”

“Yes,” Grandpa said. “She’d go in and talk to the people in there – you know, the asylum seekers, to cheer them up a bit, because they were going through hard times. She did that a lot in prisons all her life. But she never said much about it, said it upset her too much to talk about it. Once a week or so, she’d go off and make someone a little happier for a while. She was like that. She always said I should do it too, that I’d be good at it. But I never had her courage. It’s the idea of being locked up, I suppose, even if you know you can leave whenever you want to. How silly is that?”

“Do you know what Aman wrote in his letter, Grandpa?” I said. “He told me there’s six locked doors and a barbed wire fence, between him and the world outside. He counted them.”

That was the moment we turned and looked at one another, and I knew then that Grandpa had made up his mind he was going to do it. We never got to Grantchester. We turned round at once and went home, and Dog did not like that one bit.

Grandpa had been a journalist before he retired, so he knew how to find out about these things. As soon as we got back into the house, he was on the phone. He discovered that in order to visit Mrs Khan and Aman in Yarl’s Wood, he had to write a formal letter, asking permission. It took a few days before the reply came back.

The good news was that they were still there, and the people at Yarl’s Wood said that Grandpa could come on Wednesday, in two days’ time it was, and that visiting times were between two and five in the afternoon. I wrote Aman a letter at once telling him Grandpa was coming to visit him. I hoped he’d write back or phone. But he didn’t, and I couldn’t understand that at all.

All the way there I could see Grandpa was a bit nervous. He kept saying how he wished he had never agreed to do it in the first place. Dog was in the back seat, leaning his head on Grandpa’s shoulder watching the road in front, as he always did. “I think Dog would drive this car himself if you let him,” I said, trying to cheer Grandpa up a bit.

“I wish you could come in with me, Matt,” he said.

“Me too,” I told him. “But you’ll be fine, Grandpa. Just go for it. And you’ll like Aman. He’ll remember you, I know he will. And you’ve got the Monopoly, haven’t you? He’ll beat you, Grandpa. But don’t worry about that. He beats everyone. And tell him to write to me, will you? Or text, or phone?”

We were driving up a long straight hill. It seemed to lead to nowhere but the sky. Only when we reached the top of the rise did we see the gates, and then the barbed wire fence all around.

“And they keep kids in there?” Grandpa breathed.

We Want You Back

Grandpa

I left Matt and Dog in the car, and walked up towards the gates. I wasn’t looking forward to this at all. I had that same sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach that I remember from my first day at school.

An unsmiling security guard was opening the gate. He suited the place. If Matt hadn’t been there watching me from the car as I knew he must be, I’d have turned round at that point, got back in the car and gone home. But I couldn’t shame myself, I couldn’t let him down.

I turned round, and saw that Matt was already out of the car and taking Dog for a walk, as he’d said he would. We gave each other a wave, and then I was inside the gates. There was no going back now.

As I walked down the road towards the detention centre building, I tried to keep my courage up by thinking about Matt. Ever since I’ve been on my own these last two years, Matt has been to stay a lot. I love to watch him playing with Dog.

Dog is getting on these days, like me, but he is like a puppy when Matt comes. Matt keeps him young, keeps me young too. I only have to think of them both together, and they make me smile. They cheer me up. And that’s good for me. I’ve been rather down in the dumps just recently. Matt and I, we’re not just grandfather and grandson any more, we’ve become the best of friends.

But as I joined some other visitors making their way in, I was wondering what was the point of visiting Aman. After all, weren’t these asylum seekers about to be deported and sent back to where they’d come from? So what was the point? I mean, what could I do? What could I say that could make any difference?

But Matt wanted me to do it for Aman. So there I was, inside the place now, doors locking behind me, the Monopoly set under my arm. I could hear the sound of children crying.

Like all the other visitors, I was being processed. The Monopoly set had to be handed over to be checked by Security, and I got a stern ticking-off for bringing it with me in the first place. It was against the rules, but they might let me have it later, they said grudgingly.

Everywhere there were more of those unsmiling security guards. The pat-down search was done brusquely, and in hostile silence. Everything about the place seemed to me to be hateful: the bleak locker room where visitors had to leave their coats and bags, the institutional smell, the sound of keys turning in locks, the sad plastic flowers in the visitors’ meeting room, and always the sound of some child crying.

Then I saw them, the only ones still without a visitor. I recognised Aman at once, and I could tell he knew me too, as Matt had said he would. Aman and his mother were sitting there at the table, waiting for me, looking up at me, vacantly. There were no smiles. Neither of them seemed that pleased to see me. It was all too set up, too formal, too stiff. Like everyone else in the room, we had to sit facing one another on either side of a table. And there were officers everywhere, in their black and white uniforms, keys dangling from their belts, watching us.

Aman’s mother sat there, shoulders slumped, stony-faced, sad and silent. She had deep, dark rings under her eyes, and seemed locked inside herself. As for Aman, he was even smaller than I remembered, and pinched and thin like a whippet. His eyes were pools of loneliness and despair.

I kept trying to tell myself, don’t pity them. They don’t want that, they don’t need that, and they’ll know it at once if you do. They’re not victims, they’re people. Try to find something in common. Do what Matt said in the car. Just go for it. And pray the Monopoly arrives.

“How is Matt?” Aman said.

“He’s outside,” I told him. “They won’t let him in.”

Aman smiled wanly at that. “Strange,” he said. “We want to get out, and they won’t let us. And he wants to get in, but they won’t let him.”

I tried, again and again, to make some small talk with his mother. The trouble was that she spoke very little English, so Aman always had to translate for her. Aman only became animated at all, I noticed, when we talked about Matt, and even then I found myself asking all the questions. I think we’d have all sat there in silence if I hadn’t. Any question not about Matt, he’d just divert to his mother, and translate her replies, which were mostly ‘yes’ or ‘no’. However hard I tried, I just could not seem to get a proper conversation going between the three of us.

So when Aman spoke up for himself suddenly, I was taken a little by surprise. “My mother is not well,” he said. “She had one of her panic attacks this morning. The doctor gave her some medicine, and this makes her quite sleepy.” He spoke very correctly, and with hardly a trace of an accent.

“Why did she have a panic attack?” I asked, regretting my question at once. It seemed too intrusive, too personal.

“It is this place. It is being shut in here,” he replied. “She was in prison once in Afghanistan. She does not talk about it much. But I know they beat her. The police. She hates the police. She hates to be locked in. She has bad dreams of the prison in Afghanistan, you understand? So sometimes when she wakes up in here, and she sees she is in prison again, and she sees the guards, she has a panic attack.”

That was when the security guard suddenly arrived with the Monopoly game.

“You’re lucky,” he said. “Just this once, right?” And he walked away.

Miserable git, I thought. But I knew it was best to keep my feelings to myself. Now I’d got it, I didn’t want him to take it away.

“Monopoly,” I said. “Matt says you like it, that you play quite well.”

His whole face lit up. “Monopoly! Look, Mother, you remember where we played it first?” Then he turned to me. “I used to play it a lot with Matt. I never lose,” he said. “Never.”

He opened the board at once, and set it all up, rubbing his hands with delight when it was done. Then he started to laugh, and couldn’t seem to stop. “You see what it says here?” he cried, his finger stabbing at the board. “It says, ‘Go to Jail’. Go to jail! That is very funny, isn’t it? If I land here I will go to jail, in a jail. And so will you!”

His laughter was infectious, and very soon the two of us were almost hysterical.

That was when I saw another officer coming over towards us, a woman this time, but no less officious. “You’re disturbing people. Keep it down,” she said. “I won’t tell you again. Any more of that and I’ll end the visit, understand?”

She was being unnecessarily offensive, and I did not like it one bit. This time, I did not try to hide my feelings. “So we’re not allowed to laugh in here, is that right?” I protested. “People can cry, but they can’t laugh, is that it?”

The officer gave me a long, hard look, but in the end she just turned round and walked away. It was a little victory, but I could see from the smile on Aman’s face that he thought it was a lot more than that.

“Nice one,” he whispered, giving me a secretive thumbs up.

Shadow

Grandpa

Matt had been right about Aman’s prowess at Monopoly. Within an hour he owned just about all of London, and had left me bankrupt, and in jail.

“You see?” he said, punching the air with both fists in triumph. “I am very good in business, like my father was. He was a farmer. Where we used to live in Bamiyan, in Afghanistan. He had sheep, many sheep, the best sheep in the valley. And he grew apples too, big green ones. I love apples.”

“I’ve got some nice ones in my garden at home,” I told him. “Lovely pink ones. James Grieve, they’re called. I’ll bring you some next time I come.”

“They won’t let you,” he said, ruefully.

“I can try,” I told him. “I got the Monopoly game in, didn’t I?”

He smiled at that. Then, leaning forward suddenly, and ignoring his mother, he began asking me all sorts of questions, some about where I lived, what job I did, about what football team I supported – I could tell that Matt had told him a fair bit about me already, and that pleased me a lot. But Aman wanted to talk mostly about Matt, about how he’d got all his letters, and how after a while he decided he couldn’t write back, because he knew he wouldn’t be seeing Matt again, and it only made him sad.

“You mustn’t say that,” I told him. “You don’t know you won’t be seeing him again.”

“Yes I do,” he said. I knew he was right, of course, but I suppose I thought I should give him some hope.

“You never know,” I said. “You never know.”

It was then that I remembered the family photo I’d brought in with me from home, at the last moment – another of Matt’s ideas, and a good one too, I’d thought. I took it out of my jacket pocket and was about to hand it over.

Suddenly there was a guard yelling at us. Then she was striding across the room to our table – the same woman who had ticked me off before. Everyone in the room was looking at us. “It’s not allowed!” She was standing right over us by now, still shouting. “Are you just trying to make a nuisance of yourself, or what?”

Now I was properly angry, and I let her know it. “For goodness’ sake, it’s just a family photo.” I held it up to show her. “Look,” I said. She took it from me, and examined it sullenly, taking her time before giving it back to me.

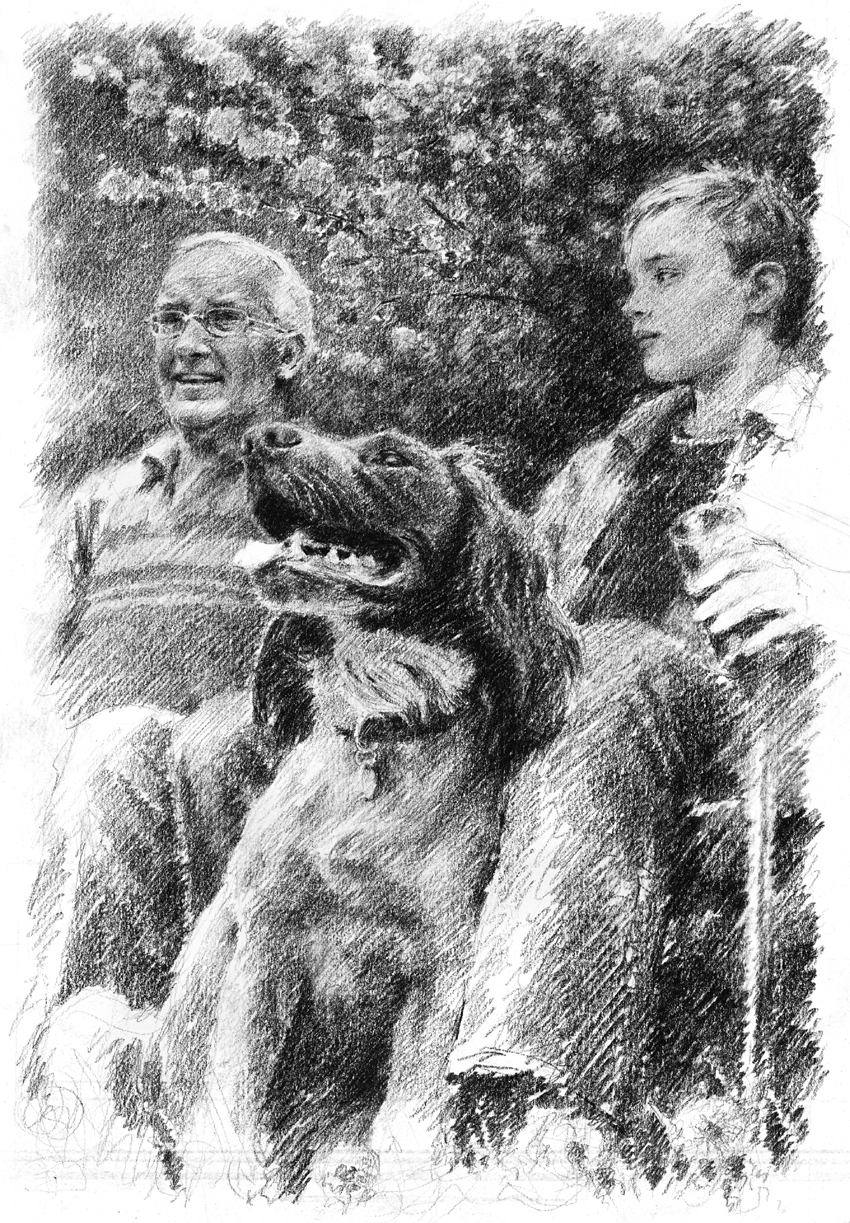

“In future,” she told me, “everything has to be passed by Security. Everything.”

I just nodded, buttoning my lip till she was gone. I hated myself for doing it, for not arguing back. But I knew that to have a stand-up row with her would be pointless – if I wanted Aman to see the photo. I waited till she’d gone away, winked triumphantly at Aman, slid the photo across the table, and then began pointing out who everyone was. “That’s the family in the garden, last summer. There’s the apple tree. And Matt, kneeling down beside Dog. Yes, I know. Not a very imaginative name for a dog, is it? I think he must be about the same age as Matt, same age as you. That’s pretty old for a dog.”