полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall, Volume 3: Conflict and construction, 1800-1815

"The sufferings inflicted on endeavors to vindicate the rights of humanity are related with all the frigid insensibility with which a monk would have contemplated the victims of an auto da fé. Let no man believe that Gen. Washington ever intended that his papers should be used for the suicide of the cause, for which he had lived, and for which there never was a moment in which he would not have died."

Marshall's "abuse of these materials," Jefferson charges, "is chiefly however manifested in the history of the period immediately following the establishment of the present constitution; and nearly with that my memorandums [the "Anas"] begin. Were a reader of this period to form his idea of it from this history alone, he would suppose the republican party (who were in truth endeavoring to keep the government within the line of the Constitution, and prevent it's being monarchised in practice) were a mere set of grumblers, and disorganisers, satisfied with no government, without fixed principles of any, and, like a British parliamentary opposition, gaping after loaves and fishes, and ready to change principles, as well as position, at any time, with their adversaries."735

Jefferson denounces Hamilton and his followers as "monarchists," "corruptionists," and other favorite Jeffersonian epithets, and Marshall is again assailed: "The horrors of the French revolution, then raging, aided them mainly, and using that as a raw head and bloody bones they were enabled by their stratagems of X. Y. Z. in which this historian was a leading mountebank, their tales of tub-plots, Ocean massacres, bloody buoys, and pulpit lyings, and slanderings, and maniacal ravings of their Gardiners, their Osgoods and Parishes, to spread alarm into all but the firmest breasts."736

Criticisms of Marshall's "Life of Washington" were not, however, confined to Jefferson and the Republicans. Plumer thought the plan of the work "preposterous."737 The Reverend Samuel Cooper Thatcher of Boston reviewed the biography through three numbers of the Monthly Anthology.738 "Every reader is surprized to find," writes Mr. Thatcher, "the history of North America, instead of the life of an individual… He [Washington] is always presented … in the pomp of the military or civil costume, and never in the ease and undress of private life." However, he considers Marshall's fifth volume excellent. "We have not heard of a single denial of his fidelity… In this respect … his work [is] unique in the annals of political history."

Thatcher concludes that Marshall's just and balanced treatment of his subject is not due to a care for his own reputation: "We are all so full of agitation and effervescence on political topicks, that a man, who keeps his temper, can hardly gain a hearing." Indeed, he complains of Marshall's fairness: he writes as a spectator, instead of as "one, who has himself descended into the arena … and is yet red with the wounds which he gave, and smarting with those which his enemies inflicted in return"; but the reviewer charges that these volumes are full of "barbarisms" and "grammatical impurities," "newspaper slang," and "unmeaning verbiage."

The Reverend Timothy Flint thought that Marshall's work displayed more intellect and labor than "eloquence and interest."739 George Bancroft, reviewing Sparks's "Washington," declared that "all that is contained in Marshall is meagre and incomplete in comparison."740 Even the British critics were not so harsh as the New York Evening Post, which pronounced the judgment that if the biography "bears any traces of its author's uncommon powers of mind, it is in the depths of dulness which he explored."741

The British critics were, of course, unsparing. The Edinburgh Review called Marshall's work "unpardonably deficient in all that constitutes the soul and charm of biography… We look in vain, through these stiff and countless pages, for any sketch or anecdote that might fix a distinguishing feature of private character in the memory… What seemed to pass with him for dignity, will, by his reader, be pronounced dullness and frigidity."742 Blackwood's Magazine asserted that Marshall's "Life of Washington" was "a great, heavy book… One gets tired and sick of the very name of Washington before he gets half through these … prodigious … octavos."743

Marshall was somewhat compensated for the criticisms of his work by an event which soon followed the publication of his last volume. On August 29, 1809, he was elected a corresponding member of the Massachusetts Historical Society. In a singularly graceful letter to John Eliot, corresponding secretary of the Society at that time, Marshall expresses his thanks and appreciation.744

As long as he lived, Marshall worried over his biography of Washington. When anybody praised it, he was as appreciative as a child. In 1827, Archibald D. Murphey eulogized Marshall's volumes in an oration, a copy of which he sent to the Chief Justice, who thanks Murphey, and adds: "That work was hurried into a world with too much precipitation, but I have lately given it a careful examination and correction. Should another edition appear, it will be less fatiguing, and more worthy of the character which the biographer of Washington ought to sustain."745

Toilsomely he kept at his self-imposed task of revision. In 1816, Bushrod Washington wrote Wayne to send Marshall "the last three volumes in sheets (the two first he has) that he may devote this winter to their correction."746

When, five years later, the Chief Justice learned that Wayne was actually considering the risk of bringing out a new edition, Marshall's delight was unbounded. "It is one of the most desirable objects I have in this life to publish a corrected edition of that work. I would not on any terms, could I prevent it, consent that one other set of the first edition should be published."747

Finally, in 1832, the revised biography was published. Marshall clung to the first volume, which was issued separately under the title "History of the American Colonies." The remaining four volumes were, seemingly, reduced to two; but they were so closely printed and in such comparatively small type that the real condensation was far less than it appeared to be. The work was greatly improved, however, and is to this day the fullest and most trustworthy treatment of that period, from the conservative point of view.748

Fortunately for Marshall, the work required of him on the Bench gave him ample leisure to devote to his literary venture. During the years he consumed in writing his "Life of Washington" he wrote fifty-six opinions in cases decided in the Circuit Court at Richmond, and in twenty-seven cases determined by the Supreme Court. Only four of them749 are of more than casual interest, and but three of them750 are of any historical consequence. All the others deal with commercial law, practice, rules of evidence, and other familiar legal questions. In only one case, that of Marbury vs. Madison, was he called upon to deliver an opinion that affected the institutions and development of the Nation.

CHAPTER VI

THE BURR CONSPIRACY

My views are such as every man of honor and every good citizen must approve. (Aaron Burr.)

His guilt is placed beyond question. (Jefferson.)

I never believed him to be a Fool. But he must be an Idiot or a Lunatic if he has really planned and attempted to execute such a Project as is imputed to him. But if his guilt is as clear as the Noonday Sun, the first Magistrate ought not to have pronounced it so before a Jury had tryed him. (John Adams.)

On March 2, 1805, not long after the hour of noon, every Senator of the United States was in his seat in the Senate Chamber. All of them were emotionally affected – some were weeping.751 Aaron Burr had just finished his brief extemporaneous address752 of farewell. He had spoken with that grave earnestness so characteristic of him.753 His remarks produced a curious impression upon the seasoned politicians and statesmen, over whose deliberations he had presided for four years. The explanation is found in Burr's personality quite as much as in the substance of his speech. From the unprecedented scene in the Senate Chamber when the Vice-President closed, a stranger would have judged that this gifted personage held in his hands the certainty of a great and brilliant career. Yet from the moment he left the Capital, Aaron Burr marched steadily toward his doom.

An understanding of the trial of Aaron Burr and of the proceedings against his agents, Bollmann and Swartwout, is impossible without a knowledge of the events that led up to them; while the opinions and rulings of Chief Justice Marshall in those memorable controversies are robbed of their color and much of their meaning when considered apart from the picturesque circumstances that produced them. This chapter, therefore, is an attempt to narrate and condense the facts of the Burr conspiracy in the light of present knowledge of them.

Although in a biography of John Marshall it seems a far cry to give so much space to that episode, the import of the greatest criminal trial in American history is not to be fully grasped without a summary of the events preceding it. Moreover, the fact that in the Burr trial Marshall destroyed the law of "constructive treason" requires that the circumstances of the Burr adventure, as they appeared to Marshall, be here set forth.

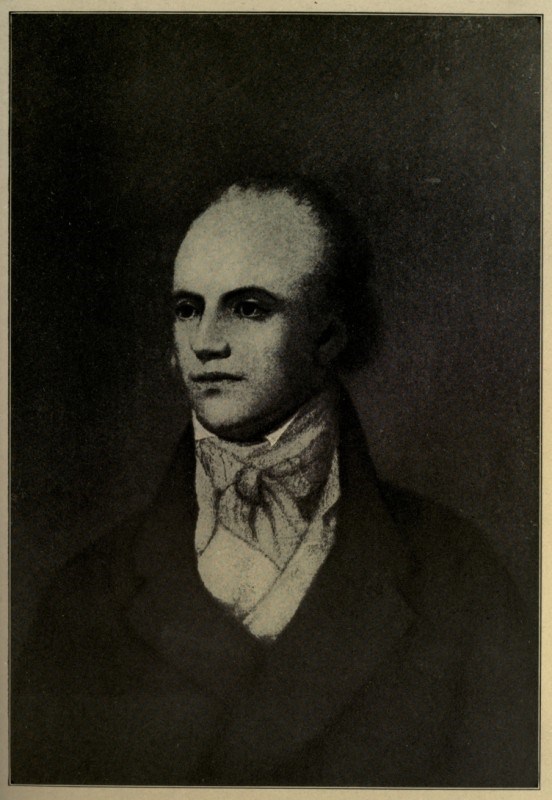

AARON BURR

A strong, brave man who, until then, had served his country well, Aaron Burr was in desperate plight when on the afternoon of March 2 he walked along the muddy Washington streets toward his lodging. He was a ruined man, financially, politically, and in reputation. Fourteen years of politics had destroyed his once extensive law practice and plunged him hopelessly into debt. The very men whose political victory he had secured had combined to drive him from the Republican Party.

The result of his encounter with Hamilton had been as fatal to his standing with the Federalists, who had but recently fawned upon him, as it was to the physical being of his antagonist. What now followed was as if Aaron Burr had been the predestined victim of some sinister astrology, so utterly did the destruction of his fortunes appear to be the purpose of a malign fate.

His fine ancestry now counted for nothing with the reigning politicians of either party. None of them cared that he came of a family which, on both sides, was among the worthiest in all the country.754 His superb education went for naught. His brilliant services as one of the youngest Revolutionary officers were no longer considered – his heroism at Quebec, his resourcefulness on Putnam's staff, his valor at Monmouth, his daring and tireless efficiency at West Point and on the Westchester lines, were, to these men, as if no such record had ever been written.

Nor, with those then in power, did Burr's notable public services in civil life weigh so much as a feather in his behalf. They no longer remembered that only a few years earlier he had been the leader of his party in the National Senate, and that his appointment to the then critically important post of Minister to France had been urged by the unanimous caucus of his political associates in Congress. None of the notable honors that admirers had asserted to be his due, nor yet his effective work for his party, were now recalled. The years of provocation755 which had led, in an age of dueling,756 to a challenge of his remorseless personal, professional, and political enemy were now unconsidered in the hue and cry raised when his shot, instead of that of his foe, proved mortal.

Yet his spirit was not broken. His personal friends stood true; his strange charm was as potent as ever over most of those whom he met face to face; and throughout the country there were thousands who still admired and believed in Aaron Burr. Particularly in the West and in the South the general sentiment was cordial to him; many Western Senators were strongly attached to him; and most of his brother officers of the Revolution who had settled beyond the Alleghanies were his friends.757 Also, he was still in vigorous middle life, and though delicate of frame and slight of stature, was capable of greater physical exertion than most men of fewer years.

What now should the dethroned political leader do? Events answered that question for him, and, beckoned forward by an untimely ambition, he followed the path that ended amid dramatic scenes in Richmond, Virginia, where John Marshall presided over the Circuit Court of the United States.

Although at the time Jefferson had praised what he called Burr's "honorable and decisive conduct"758 during the Presidential contest in the House in February of 1801, he had never forgiven his associate for having received the votes of the Federalists, nor for having missed, by the merest chance, election as Chief Magistrate.759 Notwithstanding that Burr's course as Vice-President had won the admiration even of enemies,760 his political fall was decreed from the moment he cast his vote on the Judiciary Bill in disregard of the rigid party discipline that Jefferson and the Republican leaders then exacted.761

Even before this, the constantly increasing frigidity of the President toward him, and the refusal of the Administration to recognize by appointment any one recommended by him for office in New York,762 had made it plain to all that the most Burr could expect was Jefferson's passive hostility. Under these circumstances, and soon after his judiciary vote, the spirited Vice-President committed another imprudence. He attended a banquet given by the Federalists in honor of Washington's birthday. There he proposed this impolitic toast: "To the union of all honest men." Everybody considered this a blow at Jefferson. It was even more offensive to the Administration than his judiciary vote had been.763

From that moment all those peculiar weapons which politicians so well know how to use for the ruin of an opponent were employed for the destruction of Aaron Burr. Moreover, Jefferson had decided not only that Burr should not again be Vice-President, but that his bitterest enemy from his own State, George Clinton, should be the Republican candidate for that office; and, in view of Burr's strength and resourcefulness, this made necessary the latter's political annihilation.764 "Never in the history of the United States did so powerful a combination of rival politicians unite to break down a single man as that which arrayed itself against Burr."765

Nevertheless, Burr, who "was not a vindictive man,"766 did not retaliate for a long time.767 But at last to retrieve himself,768 he determined to appeal to the people – at whose hands he had never suffered defeat – and, in 1804, he became a candidate for the office of Governor of New York. The New York Federalists, now reduced to a little more than a strong faction, wished to support him, and were urged to do so by many Federalist leaders of other States. Undoubtedly Burr would have been elected but for the attacks of Hamilton.

At this period the idea of secession was stirring in the minds of the New England Federalist leaders. Such men as Timothy Pickering, Roger Griswold, Uriah Tracy, and James Hillhouse had even avowed separation from the Union to be desirable and certain; and talk of it was general.769 All these men were warm and insistent in their support of Burr for Governor, and at least two of them, Pickering and Griswold, had a conference with him in New York while the campaign was in progress.

Plumer notes in his diary that during the winter of 1804, at a dinner given in Washington attended by himself, Pickering, Hillhouse, Burr, and other public men, Hillhouse "unequivocally declared that … the United States would soon form two distinct and separate governments."770 More than nine months before, certain of the most distinguished New England Federalists had gone to the extreme length of laying their object of national dismemberment before the British Minister, Anthony Merry, and had asked and received his promise to aid them in their project of secession.771

There was nothing new in the idea of dismembering the Union. Indeed, no one subject was more familiar to all parts of the country. Since before the adoption of the Constitution, it had been rife in the settlements west of the Alleghanies.772 The very year the National Government was organized under the Constitution, the settlers beyond the Alleghanies were much inclined to withdraw from the Union because the Mississippi River had not been secured to them.773 For many years this disunion sentiment grew in strength. When, however, the Louisiana Purchase gave the pioneers on the Ohio and the Mississippi a free water-way to the Gulf and the markets of the world, the Western secessionist tendency disappeared. But after the happy accident that bestowed upon us most of the great West as well as the mouth of the Mississippi, there was in the Eastern States a widely accepted opinion that this very fact made necessary the partitioning of the Republic.

Even Jefferson, as late as 1803, did not think that outcome unlikely, and he was prepared to accept it with his blessing: "If they see their interest in separation, why should we take sides with our Atlantic rather than our Mississippi descendants? It is the elder and the younger brother differing. God bless them both, and keep them in union, if it be for their good, but separate them, if it be better."774

Neither Spain nor Great Britain had ever given over the hope of dividing the young Republic and of acquiring for themselves portions of its territory. The Spanish especially had been active and unceasing in their intrigues to this end, their efforts being directed, of course, to the acquisition of the lands adjacent to them and bordering on the Mississippi and the Ohio.775 In this work more than one American was in their pay. Chief of these Spanish agents was James Wilkinson, who had been a pensioner of Spain from 1787,776 and so continued until at least 1807, the bribe money coming into his hands for several years after he had been placed in command of the armies of the United States.777

None of these plots influenced the pioneers to wish to become Spanish subjects; the most that they ever desired, even at the height of their dissatisfaction with the American Government, was independence from what they felt to be the domination of the East. In 1796 this feeling reached its climax in the Kentucky secession movement, one of its most active leaders being Wilkinson, who declared his purpose of becoming "the Washington of the West."778

By 1805, however, the allegiance of the pioneers to the Nation was as firm as that of any other part of the Republic. They had become exasperated to the point of violence against Spanish officials, Spanish soldiers, and the Spanish Government. They regarded the Spanish provinces of the Floridas and of Mexico as mere satrapies of a hated foreign autocracy; and this indeed was the case. Everywhere west of the Alleghanies the feeling was universal that these lands on the south and southwest, held in subjection by an ancient despotism, should be "revolutionized" and "liberated"; and this feeling was shared by great numbers of people of the Eastern States.

Moreover, that spirit of expansion – of taking and occupying the unused and misused lands upon our borders – which has been so marked through American history, was then burning fiercely in every Western breast. The depredations of the Spaniards had finally lashed almost to a frenzy the resentment which had for years been increasing in the States bordering upon the Mississippi. All were anxious to descend with fire and sword upon the offending Spaniards.

Indeed, all over the Nation the conviction was strong that war with Spain was inevitable. Even the ultra-pacific Jefferson was driven to this conclusion; and, in less than ten months after Aaron Burr ceased to be Vice-President, and while he was making his first journey through the West and Southwest, the President, in two Messages to Congress, scathingly arraigned Spanish misdeeds and all but avowed that a state of war actually existed.779

Such, in broad outline, was the general state of things when Aaron Burr, his political and personal fortunes wrecked, cast about for a place to go and for work to do. He could not return to his practice in New York; there his enemies were in absolute control and he was under indictment for having challenged Hamilton. The coroner's jury also returned an inquest of murder against Burr and two of his friends, and warrants for their arrest were issued. In New Jersey, too, an indictment for murder hung over him.780

Only in the fresh and undeveloped West did a new life and a new career seem possible. Many projects filled his mind – everything was possible in that inviting region beyond the mountains. He thought of forming a company to dig a canal around the falls of the Ohio and to build a bridge over that river, connecting Louisville with the Indiana shore. He considered settling lands in the vast dominions beyond the Mississippi which the Nation had newly acquired from Spain. A return to public life as Representative in Congress from Tennessee passed through his mind.

But one plan in particular fitted the situation which the apparently certain war with Spain created. Nearly ten years earlier,781 Hamilton had conceived the idea of the conquest of the Spanish possessions adjacent to us, and he had sought to enlist the Government in support of the project of Miranda to revolutionize Venezuela.782 Aaron Burr had proposed the invasion and capture of the Floridas, Louisiana, and Mexico two years before Hamilton embraced the project,783 and the desire to carry out the plan continued strong within him. Circumstances seemed to make the accomplishment of it feasible. At all events, a journey through the West would enlighten him, as well as make clearer the practicability of his other schemes.

Now occurred the most unfortunate and disgraceful incident of Burr's life. In order to get money for his Mexican adventure, Burr played upon the British Minister's hostile feelings toward America and, in doing so, used downright falsehood. Although it was unknown at the time and not out of keeping with the unwritten rules of the game called diplomacy as then played, and although it had no effect upon the thrilling events that brought Burr before Marshall, so inextricably has this shameful circumstance been woven into the story of the Burr conspiracy, that mention of it must be made. It was the first thoroughly dishonorable act of Burr's tempestuous career.784

Five months after Pickering, Griswold, and other New England Federalists had approached Anthony Merry with their plan to divide the Union, Burr prepared to follow their example. He first sounded that diplomat through a British officer, one Colonel Charles Williamson. The object of the New England Senators and Representatives had been to separate their own and other Northern States from the Union; the proposition that Williamson now made to the British Minister was that Burr might do the same thing for the Western States.785 It was well known that the break-up of the Republic was expected and hoped for by the British Government, as well as by the Spaniards, and Williamson was not surprised when he found Merry as favorably disposed toward a scheme for separation of the States beyond the Alleghanies as he had been hospitable to the plan for the secession of New England.

Of the results of this conference Burr was advised; and when he had finished his preparations for his journey down the Ohio, he personally called upon Merry. This time a part of his real purpose was revealed; it was to secure funds.786 Burr asked that half a million dollars be supplied him787 for the revolutionizing of the Western States, but he did not tell of his dream about Mexico, for the realization of which the money was probably to be employed. In short, Burr lied; and in order to persuade Merry to secure for him financial aid he proposed to commit treason. Henry Adams declares that, so far as the proposal of treason was concerned, there was no difference between the moral delinquency of Pickering, Griswold, Hillhouse, and other Federalists and that of Aaron Burr.788

The eager and credulous British diplomat promised to do his best and sent Colonel Williamson on a special mission to London to induce Pitt's Ministry to make the investment.789 It should be repeated that Burr's consultations with the shallow and easily deceived Merry were not known at the time. Indeed, they never were fully revealed until more than three quarters of a century afterward.790 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that they had little or no bearing upon the adventure which Burr finally tried to carry out.791 He was, as has been said, audaciously and dishonestly playing upon Merry's well-known hostility to this country in order to extract money from the British Treasury.792 This attempt and the later one upon the Spanish Minister, who was equally antagonistic to the United States, were revolting exhibitions of that base cunning and duplicity which, at that period, formed so large a part of secret international intrigue.793