полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall, Volume 3: Conflict and construction, 1800-1815

Other solicitors, however, were also put to work: among them the picturesque Mason Locke Weems, part Whitefield, part Villon, a delightful mingling of evangelist and vagabond, lecturer and politician, writer and musician.609 Weems had himself written a "Life of Washington" which had already sold extensively among the common people.610 He had long been a professional book agent with every trick of the trade at his fingers' ends, and was perfectly acquainted with the popular taste.

First, the parson-subscription agent hied himself to Baltimore. "I average 12 subs pr day. Thank God for that," he wrote to his employer. He is on fire with enthusiasm: "If the Work be done handsomely, you will sell at least 20,000," he brightly prophesies. Within a week Weems attacks the postmasters and insists that he be allowed to secure sub-agents from among the gentry: "The Mass of Riches and of Population in America lie in the Country. There is the wealthy Yeomanry; and there the ready Thousands who wd. instantly second you were they but duly stimulated."611

Almost immediately Weems discovered a popular distrust of Marshall's forthcoming volumes: "The People are very fearful that it will be prostituted to party purposes," he informs Wayne. "For Heaven's Sake, drop now and then a cautionary Hint to John Marshall Esq. Your all is at stake with respect to this work. If it be done in a generally acceptable manner you will make your fortune. Otherwise the work will fall an Abortion from the press."612

Weems's apprehension grew. Wayne had written that the cities would yield more subscribers than the country. "For a moment, admit it," argues Weems: "Does it follow that the Country is a mere blank, a cypher not worth your notice? Because there are 30,000 wealthy families in the City and but 20,000 in the Country, must nothing be tried to enlist 5000, at least of these 20,000??? If the Feds shd be disappointed, and the Demos disgusted with Genl. Marshals performance, will it not be very convenient to have 4 to 5000 good Rustic Blades to lighten your shelves & to shovel in the Dol$."613

The dean of book agents evidently was having a hard time, but his resourcefulness kept pace with his discouragement: "Patriotic Orations – Gazetter Puffs – Washingtonian Anecdotes, Sentimental, Moral Military and Wonderful – All shd be Tried," he advises Wayne.614 Again, he notes the failure of the postmasters to sell Marshall's now much-talked-of book. "In six months," he writes from Martinsburg, Virginia, "the P. Master here got 1. In ½ day. I thank God, I've got 13 subs."615

The outlook for subscriptions was even worse in New England. Throughout the whole land, there was, it seems, an amazing indifference to Washington's services to the Nation. "I am sorry to inform you," Wayne advised Marshall and his associate, "that the Prospect of an extensive Subscription is gloomy in N. England, particularly they argue it is too Expensive and wait for a cheaper Edition – 'tis like Americans, Mr. Wolcott and Mr. Pickering say they are loud in their professions, but attempt to touch their purses and they shut them in a moment."616

Writing from Fredericksburg, Virginia, Weems at last mingles cheer with warning: "Don't indulge a fear – let no sigh of thine arise. Give Old Washington fair play and all will be well. Let but the Interior of the Work be Liberal & the Exterior Elegant, and a Town House & a Country House, a Coach and Sideboard and Massy Plate shall be thine." Still, he declared, "I sicken when I think how much may be marrd."617

A week later found the reverend solicitor at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and here the influence of politics on the success of Marshall's undertaking again crops out: "The place had been represented to me," records Weems, "as a Nest of Anti Washingtonian Hornets who wd draw their Stings at mention of his name – and the Fed [torn] Lawyers are all gone to York – However, I dashd in among them and thank God have obtaind already 17 good names."618

By now even the slow-thinking Bushrod Washington had become suspicious of Jefferson's postmasters: "The postmasters being (I believe) Democrats.619 Are you sure they will feel a disposition to advance the work?"620 Later he writes: "I would not give one honest soliciting agent for 1250 quiescent postmasters."621

A year passed after the first subscriptions were made, and not even the first volume had appeared. Indeed, no part of the manuscript had been finished and sent to the publisher. Wayne was exasperated. "I am extremely anxious on this subject," he complains to Bushrod Washington, "as the Public evince dissatisfaction at the delay. Each hour I am questioned either verbally or by letter relative to it & its procrastination. The subscription seems to have received a check in consequence of an opinion that it is uncertain when the work will go to press. Twelve thousand dollars is the Total Cash yet reced– not quite 4,000 subscribers."622

By November, 1803, many disgusted subscribers are demanding a refund of the money, and Wayne wants the contract changed to the payment of a lump sum. The "Public [are] exclaiming against the price of 3 Dolls per vol.," and his sanguine expectations have evaporated: "I did hope that I should realize half the number of subscribers you contemplated, thirty thousand; … but altho' two active, and twelve hundred other agents have been employed 12 months, the list of names does not amount to one seventh of the contemplated number."623

Wayne insists on purchasing the copyright "for a moderate, specifick sum" so that he can save himself from loss and "that the Publick disgust may be removed." He has heard, he says, and quite directly, that the British rights have been sold "at two thousand dolls!!!" – and this in spite of the fact that, only the previous year, Marshall and Washington "expected Seventy Thousand."624

At last, more than three years after Marshall had decided to embark upon the uncertain sea of authorship, he finished the first of the five volumes. And such a mass of manuscript! "It will make at least Eight hundred pages!!!!" moaned the distraught publisher. At that rate, considering the small number of subscribers and the greatly increased cost of paper and labor,625 Wayne would be ruined. No title-page had been sent, and Marshall's son, who had brought the manuscript to Philadelphia, "astonished" Wayne by telling him "that his father's name was not to appear in the Title."626

When Marshall learned that the publisher demanded a title-page bearing his name, he insisted that this was unnecessary and not required by the copyright law. "I am unwilling," he hastened to write Wayne, "to be named in the book or in the clerk's office as the author of it, if it be avoidable." He cannot tell how many volumes there will be, or even examine, before some time in May, 1804, Washington's papers relating to the period of his two administrations. The first volume he wants "denominated an introduction." It is too long, he admits, and authorizes Wayne to split it, putting all after "the peace of 1763" into the second volume.627

Marshall objects again to appearing as the author: "My repugnance to permitting my name to appear in the title still continues, but it shall yield to your right to make the best use you can of the copy." He does not think that "the name of the author being given or withheld can produce any difference in the number of subscribers"; but, since he does not wish to leave Wayne "in the Opinion that a real injury has been sustained," he would "submit scruples" to Wayne and Washington, "only requesting that [his] name may not be given but on mature consideration and conviction of its propriety." In any case, Marshall declares: "I wish not my title in the judiciary of the United States to be annexed to it."

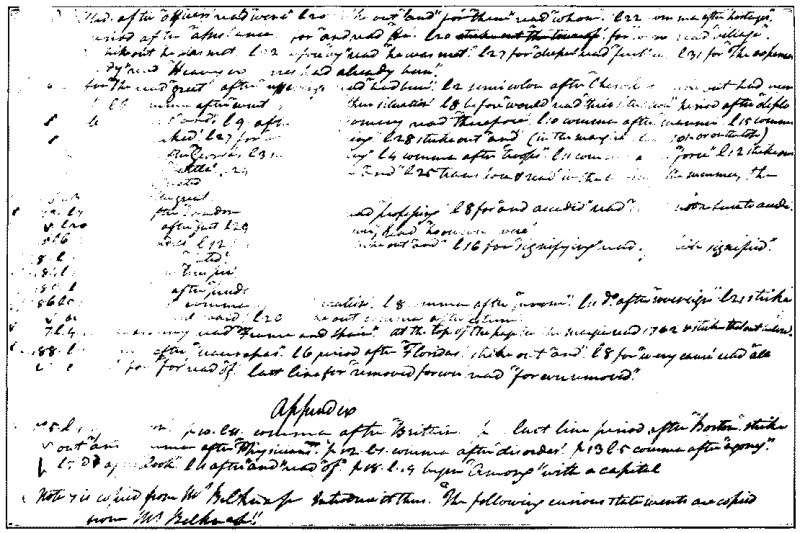

He writes at great length about punctuation, paragraphing, capital letters, and spelling, giving minute directions, but leaves much to Wayne's judgment. As to spelling: "In any doubtful case I woud decidedly prefer to follow Johnson."628 Two other long letters about details of printing the first volume followed. By the end of March, 1804, his second volume was ready.629

He now becomes worried about "the inaccuracies … the many and great defects in composition" of the first two volumes; but "the hurried manner in which it is pressd forward renders this inevitable." He begs Bushrod Washington to "censure and alter freely… You mistake me very much if you think I rank the corrections of a friend with the bitter sarcasms of a foe, or that I shoud feel either wounded or chagrined at my inattentions being pointed out by another."630

Once more the troubled author writes his associate, this time about the spelling of "Chesapeak" and "enterprise," the size of the second volume, and as to "the prospects of subscribers."631 Not until June, 1804, did Marshall give the proof-sheets of the first volume even "a hasty reading" because of "the pressure of … official business."632 Totally forgotten was the agreed plan to publish maps in a separate volume, although it was thus "stated in the prospectus."633 He blandly informs the exasperated publisher that he must wait a long time after publishing the volumes describing the Revolution and those on the Presidency of Washington before the manuscript of the last volume can be sent to press – this when many subscribers were clamoring for the return of the money they had paid, and the public was fast losing interest in the book. Large events had meanwhile filled the heavens of popular interest, and George Washington's heroic figure was already becoming dim and indistinct.

The proof-sheets of the second volume were now in Marshall's hands; but the toil of writing, "super-intending the copying," and various other avocations "absolutely disabled" him, he insists, from giving them any proper examination. He had no idea that he had been so careless in his writing and is anxious to revise the work for a second edition. He complains of his health and says he must spend the summer in the mountains, where, of course, he "cannot take the papers with [him] to prosecute the work." He will, however, read the pages of the first two volumes while on his vacation.

The manuscript of the third he had finished and sent to Bushrod Washington.634 When Wayne saw the length of it, his Quaker blood was heated to wrath. Did Marshall's prolixity know no limit? The first two volumes had already cost the publisher far more than the estimate – would not Washington persuade Marshall to be more concise?635

By midsummer of 1804 the first two volumes appeared. They were a dismal performance. Nevertheless, one or two Federalist papers praised them, and Marshall was as pleased as any youthful writer by a first compliment. He thanks Wayne for sending the reviews and comments on one of them: "The very handsome critique in the 'Political and Commercial Register' was new to me." He modestly admits: "I coud only regret that there was in it more of panuegyric than was merited. The editor … manifests himself to be master of a style of a very superior order and to be, of course, a very correct judge of the composition of Others."

A PART OF MARSHALL'S LIST OF CORRECTIONS FOR HIS LIFE OF WASHINGTON

Marshall is somewhat mollified that his parentage of the biography has been revealed: "Having, Heaven knows how reluctantly, consented against my judgement to be known as the author of the work in question I cannot be insensible to the opinions entertained of it. But, I am much more solicitous to hear the strictures upon it" – than commendation of it – because, he says, these would point out defects to be corrected. He asks Wayne, therefore, to send to him at Front Royal, Virginia, "every condemnatory criticism… I shall not attempt to polish every sentence; that woud require repeated readings & a long course of time; but I wish to correct obvious imperfections & the animadversions of others woud aid me very much in doing so."636

Within three weeks Marshall had read his first volume in the form in which it had been delivered to subscribers, and was "mortified beyond measure to find that it [had] been so carelessly written." He had not supposed that so many "inelegancies … coud have appeared in it," and regrets that he must require Wayne to reset the matter "so materially." He informs his publisher, nevertheless, that he is starting on his vacation in the Alleghanies; and he promises that when he returns he "will … review the corrections" he has made in the first volume, although he would "not have time to reperuse the whole volume."637

Not for long was the soul of the perturbed author to be soothed with praise. He had asked for "strictures"; he soon got them. Wayne promptly sent him a "Magazine638 containing a piece condemnatory of the work." Furthermore, the books were not going well; not a copy could the publisher sell that had not been ordered before publication. "I have all those on hand which I printed over the number of subscribers," Wayne sourly informs the author.

In response to Marshall's request for time for revision, Wayne is now willing that he shall take all he wishes, since "present prospects would not induce [him] to republish," but he cautions Marshall to "let the idea of a 2d edit. revised and corrected remain a secret"; if the public should get wind of such a purpose the stacks of volumes in Wayne's printing house would never be sold. He must have the manuscript of the "fourth vol. by the last of September at furthest… Can I have it? – or must I dismiss my people."

At the same time he begs Marshall to control his redundancy: "The first and second vols. have cost me (1500) fifteen hundred dollars more than calculated!"639

It was small wonder that Marshall's first two bulky books, published in the early summer of 1804, were not hailed with enthusiasm. In volume one the name of Washington was mentioned on only two minor occasions described toward the end.640 The reader had to make his way through more than one hundred thousand words without arriving even at the cradle of the hero. The voyages of discovery, the settlements and explorations of America, and the history of the Colonies until the Treaty of Paris in 1763, two years before the Stamp Act of 1765, were treated in dull and heavy fashion.

The author defends his plan in the preface: No one connected narrative tells the story of all the Colonies and "few would … search through the minute details"; yet this he held to be necessary to an understanding of the great events of Washington's life. So Marshall had gathered the accounts of the various authorities641 in parts of the country and in England, and from them made a continuous history. If there were defects in the book it was due to "the impatience … of subscribers" which had so hastened him.

The volume is poorly done; parts are inaccurate.642 To Bacon's Rebellion are given only four pages.643 The story of the Pilgrims is fairly well told.644 A page is devoted to Roger Williams and six sympathetic lines tell of his principles of liberty and toleration.645 The Salem witchcraft madness is well treated.646 The descriptions of military movements constitute the least disappointing parts of the volume. The beginnings of colonial opposition to British rule are tiresomely set out; and thus at last, the reader arrives within twelve years of Bunker Hill.

Marshall admits that every event of the Revolutionary War has been told by others who had examined Washington's "immensely voluminous correspondence," and that he had copied these authors, sometimes using their very language. Still, he promises the reader "a particular account of his [Washington's] own life."647

One page and three lines at the beginning of the second volume are all that Marshall gives of the ancestry, birth, environment, upbringing, education, and experiences of George Washington, up to the nineteenth year of his age. On the second page the hero, fully uniformed and accoutred, is plunged into the French and Indian Wars. Braddock's defeat, already described in the first volume, is repeated and elaborated.648 Six lines, closing the first chapter, disposes of Washington in marriage and describes the bride.649

About three pages are devoted to the Stamp Act speeches in the British Parliament; while but one short paragraph is given to the immortal resolutions of Patrick Henry and the passage of them by the Virginia House of Burgesses. Not a word describes the "most bloody" debate over them, and Henry's time-surviving speech is not even referred to.650 All mention of the fact that Washington was a fellow member with Henry and voted for the resolutions is omitted. Henry's second epoch-making speech at the outbreak of the Revolution is not so much as hinted at, nor is any place found for the Virginia Resolutions for Arming and Defense, which his unrivaled eloquence carried.

The name of the supreme orator of the Revolution is mentioned for the second time in describing the uprising against Lord Dunmore,651 and then Marshall adds this footnote: "The same gentleman who had introduced into the assembly of Virginia the original resolution against the stamp act."652

Marshall's account of the development of the idea of independence is scattered.653 He gives with unnecessary completeness certain local resolutions favoring it,654 while to the great Declaration less than two pages655 are assigned. It is termed "this important paper"; and a footnote disposes of the fact that "Mr. Jefferson, Mr. John Adams, Mr. Franklin, Mr. Sherman, and Mr. R. R. Livingston, were appointed to prepare this declaration; and the draft reported by the committee has been generally attributed to Mr. Jefferson."656 A report of the talk between Washington and Colonel Paterson of the British Army, concerning the title by which Washington insisted upon being addressed,657 is given one and one third times the space that is bestowed upon the Declaration of Independence.

Marshall is satisfactory only when dealing with military operations. He draws a faithful picture of the condition of the army;658 quotes Washington's remorseless condemnations of the militia,659 short enlistments, and the democratic spirit among men and officers.660 When writing upon such topics, Marshall is spirited; his pages are those of the soldier that, by nature, he was.

The earliest objection to Marshall's first two volumes came from American Tories, who complained of the use of the word "enemy" as applied to the British military forces. Wayne reluctantly calls Marshall's attention to this. Marshall replies: "You need make no apology for mentioning to me the criticism of the word 'enemy.' I will endeavor to avoid it where it can be avoided."661

Unoffended by such demands, Marshall was deeply chagrined by other and entirely just criticisms. Why, he asks, had not some one pointed out to him "some of those objections … to the plan of the work" before he wrote any part of it? He wishes "very sincerely" that this had been done. He "should very readily have relinquished [his own] opinion … if [he] had perceivd that the public taste required a different course." Thus, by implication, he blames Wayne or Bushrod Washington, for his own error of judgment.

Marshall also reproaches himself, but in doing so he saddles on the public most of the burden of his complaints: "I ought, indeed, to have foreseen that the same impatience which precipitated the publication woud require that the life and transactions of Mr. Washington should be immediately entered upon." Even if he had stuck to his original plans, still, he "ought to have departed from them so far as to have composed the introductory volume at leizure after the principal work was finished."

Marshall's "mortification" is, he says, also "increased on account of the careless manner in which the work has been executed." For the first time in his life he had been driven to sustained and arduous mental labor, and he found, to his surprise, that he "had to learn that under the pressure of constant application, the spring of the mind loses its elasticity… But regrets for the past are unavailing," he sighs. "There will be great difficulty in retrieving the reputation of the first volume… I have therefore some doubts whether it may not be as well to drop the first volume for the present – that is not to speak of a republication of it."

He assures Wayne that he need have no fears that he will mention a revised edition, and regrets that the third volume is also too long; his pen has run away with him. He would shorten it if he had the copy once more; but since that cannot be, perhaps Wayne might omit the last chapter. Brooding over the "strictures" he had so confidently asked for, he grows irritable. "Whatever might have been the execution, the work woud have experienced unmerited censure. We must endeavor to rescue what remains to be done from such [criticism] as is deserved. I wish you to consult Mr. Washington."662

Another very long letter from Front Royal quickly follows. Marshall again authorizes the publisher himself to cut the bulk of the third volume, in the hope that it "will not be so defective… It shall be my care to render the 4th more fit for the public eye." He promises Wayne that, in case of a second edition,663 he will shorten his interminable pages which shall also "receive very material corrections." But a corrected and improved edition! "On this subject … I remain silent… Perhaps a free expression of my thoughts … may add to the current which seems to set against it." Let the public take the first printing "before a second is spoken of."664

Washington drew on the publisher665 and wrote Wayne that "the disappointment will be very great if it is not paid." In December, 1804, Wayne sent the first royalty. It amounted to five thousand dollars.666

Our author needed money badly. "I do not wish to press you upon the subject of further remittances but they will be highly acceptable," Washington tells Wayne, "particularly to Mr. Marshall, whose arrangements I know are bottomed upon the expectation of the money he is to receive from you."667 In January, 1805, Wayne sent Washington another thousand dollars – "which I have paid," says Washington, "to Mr. Marshall as I shall also do of the next thousand you remit."668 Thus pressed, Wayne sends more money, and by January 1, 1805, Marshall and Washington have received the total sum of eight thousand seven hundred and sixty dollars.669

Toward the end of February, 1805, Marshall completed the manuscript of the fourth volume. He was then in Washington, and sent two copies from there to Philadelphia by Joseph Hopkinson, who had just finished his notable work in the Chase impeachment trial. "They are both in a rough state; too rough to be sent … but it was impossible to have them recopied," Marshall writes Wayne. He admits they are full of errors in capitalization, punctuation, and spelling, but adds, "it has absolutely been impossible to make corrections in these respects."670 This he "fears will produce considerable difficulty." Small wonder, with the Chase trial absorbing his every thought and depressing him with heavy anxiety.

Marshall's relief from the danger of impeachment is at once reflected in his correspondence with Wayne. Two weeks after the acquittal of Chase, he placidly informs his publisher that the fifth volume will not be ready until the spring of 1806 at the earliest. It is "not yet commenced," he says, "but I shall however set about it in a few days." He explains that there will be little time to work on the biography. "For the ensuing twelve months I shall scarcely have it in my power to be five in Richmond."671 Three months later he informs Wayne that it will be "absolutely impossible" to complete the final volume by the time mentioned. "I regret this very seriously but it is a calamity for which there is no remedy."

The cause of this irremediable calamity was "a tour of the mountains" – a journey to be made "for [his] own health and that of [his] family" from which he "cannot return till October." He still "laments sincerely that an introductory volume was written because [he] finds it almost impossible to compress the civil administration into a single volume. In doing it," he adds, "I shall be compelled to omit several interesting transactions & to mutilate others."672

At last Marshall's eyes are fully opened to what should have been plain to him from the first. Nobody wanted a tedious history of the discovery and settlement of America and of colonial development, certainly not from his pen. The subject had been dealt with by more competent authors.