полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall, Volume 3: Conflict and construction, 1800-1815

On April 10, 1805, Burr left Philadelphia on horseback for Pittsburgh, where he arrived after a nineteen days' journey. Before starting he had talked over his plans with several friends, among them former Senator Jonathan Dayton of New Jersey, who thereafter was a partner and fellow "conspirator."794

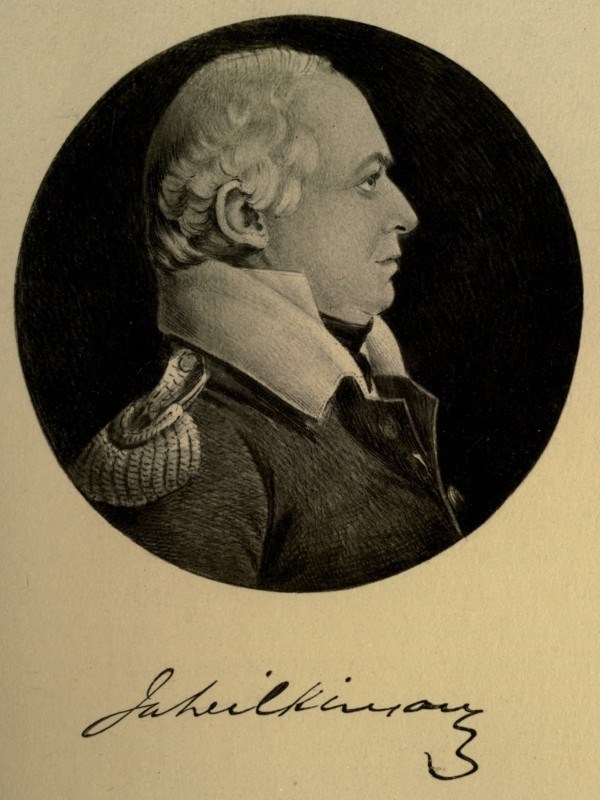

Another man with whom Burr had conferred was General James Wilkinson. Burr expected to meet him at Pittsburgh, but the General was delayed and the meeting was deferred. Wilkinson had just been appointed Governor of Upper Louisiana – one of the favors granted Burr during the Chase impeachment – and was the intimate associate of the fallen politician in his Mexican plan until, in a welter of falsehood and corruption, he betrayed him. Indeed, it was Wilkinson who, during the winter of 1804-05, when Burr was considering his future, proposed to him the invasion of Mexico and thus gave new life to Burr's old but never abandoned hope.795

On May 2, Burr started down the Ohio. When he reached Marietta, Ohio, he was heartily welcomed. He next stopped at an island owned by Harman Blennerhassett, who happened to be away. While inspecting the grounds Burr was invited by Mrs. Blennerhassett to remain for dinner. Thus did chance lay the foundations for that acquaintance which, later, led to a partnership in the enterprise that was ended so disastrously for both.

At Cincinnati, then a town of some fifteen hundred inhabitants, the attentions of the leading citizens were markedly cordial. There Burr was the guest of John Smith, then a Senator from Ohio, who had become attached to Burr while the latter was Vice-President, and who was now one of his associates in the plans under consideration. At Smith's house he met Dayton, and with these friends and partners he held a long conversation on the various schemes they were developing.796

A week later found him at the "unhealthy and inconsiderable village"797 of Louisville and from there he traveled by horseback to Frankfort and Lexington. While in Kentucky he conferred with General John Adair, then a member of the National Senate, who, like Smith and Dayton, had in Washington formed a strong friendship for Burr, and was his confidant.798 Another eminent man with whom he consulted was John Brown, then a member of the United States Senate from Kentucky, also an admirer of Burr.

It would appear that the wanderer was then seriously considering the proposal, previously made by Matthew Lyon, now a Representative in Congress from Kentucky, that Burr should try to go to the National House from Tennessee,799 for Burr asked and received from Senator Brown letters to friends in that State who could help to accomplish that design. But not one word did Burr speak to General Adair, to Senator Brown, or to any one else of his purpose to dismember the Nation.

Burr arrived at Nashville at the end of the month. The popular greeting had grown warmer with each stage of his journey, and at the Tennessee Capital it rose to noisy enthusiasm. Andrew Jackson, then Major-General of the State Militia, was especially fervent and entertained Burr at his great log house. A "magnificent parade" was organized in his honor. From miles around the pioneers thronged into the frontier Capital. Flags waved, fifes shrilled, drums rolled, cannon thundered. A great feast was spread and Burr addressed the picturesque gathering.800 Never in the brightest days of his political success had he been so acclaimed. Jackson, nine years before, when pleading with Congress to admit Tennessee into the Union, had met and liked Burr, who had then advocated statehood for that vigorous and aggressive Southern Territory. Jackson's gratitude for Burr's services to the State in championing its admission,801 together with his admiration for the man, now ripened into an ardent friendship.

His support of Burr well reflected that of the people among whom the latter now found himself. Accounts of Burr's conduct as presiding officer at the trial of Chase had crept through the wilderness; the frontier newspapers were just printing Burr's farewell speech to the Senate, and descriptions of the effect of it upon the great men in Washington were passing from tongue to tongue. All this gilded the story of Burr's encounter with Hamilton, which, from the beginning, had been applauded by the people of the West and South.

Burr was now in a land of fighting men, where dueling was considered a matter of honor rather than disgrace. He was in a rugged democracy which regarded as a badge of distinction, instead of shame, the killing in fair fight of the man it had been taught to believe to be democracy's greatest foe. Here, said these sturdy frontiersmen, was the captain so long sought for, who could lead them in the winning of Texas and Mexico for America; and this Burr now declared himself ready to do – a purpose which added the final influence toward the conquest of the mind and heart of Andrew Jackson.

Floating down the Cumberland River in a boat provided by Jackson, Burr encountered nothing but friendliness and encouragement. At Fort Massac he was the guest of Wilkinson, with whom he remained for four days, talking over the Mexican project. Soon afterward he was on his way down the Mississippi from St. Louis in a larger boat with colored sails, manned by six soldiers – all furnished by Wilkinson. After Burr's departure Wilkinson wrote to Adair, with whom he had served in the Indian wars, that "we must have a peep at the unknown world beyond me."

On June 25, 1805, Burr landed at New Orleans, then the largest city west of the Alleghanies. There the ovation to the "hero" surpassed even the demonstration at Nashville. Again came dinners, balls, fêtes, and every form of public and private favor. So perfervid was the welcome to him that the Sisters of the largest nunnery in Louisiana invited Burr to visit their convent, and this he did, under the conduct of the bishop.802 Wilkinson had given him a letter of introduction to Daniel Clark, the leading merchant of the city and the most influential man in Louisiana. The letter contained this cryptic sentence: "To him [Burr] I refer you for many things improper to letter, and which he will not say to any other."803

The notables of the city were eager to befriend Burr and to enter into his plans. Among them were John Watkins, Mayor of New Orleans, and James Workman, Judge of the Court of Orleans County. These men were also the leading members of the Mexican Association, a body of three hundred Americans devoted to effecting the "liberation" of Mexico – a design in which they accurately expressed the general sentiment of Louisiana. The invasion of Mexico had become Burr's overmastering purpose, and it gathered strength the farther he journeyed among the people of the West and South. To effect it, definite plans were now made.804

The Catholic authorities of New Orleans approved Burr's project, and appointed three priests to act as agents for the revolutionists in Mexico.805 Burr's vision of Spanish conquest seemed likely of realization. The invasion of Mexico was in every heart, on every tongue. All that was yet lacking to make it certain was war between Spain and the United States, and every Western or Southern man believed that war was at hand.

Late in July, Burr, with justifiably high hope, left New Orleans by the overland route for Nashville, riding on horses supplied by Daniel Clark. Everywhere he found the pioneers eager for hostilities. At Natchez the people were demonstrative. By August 6, Burr was again with Andrew Jackson, having ridden over Indian trails four hundred and fifty miles through the swampy wilderness.806

The citizens of Nashville surpassed even their first welcome. At the largest public dinner ever given in the West up to that time, Burr entered the hall on Jackson's arm and was received with cheers. Men and women vied with one another in doing him honor. The news Burr brought from New Orleans of the headway that was being made regarding the projected descent upon the Spanish possessions, thrilled Jackson; and his devotion to the man whom all Westerners and Southerners had now come to look upon as their leader knew no bounds.807 For days Jackson and Burr talked of the war with Spain which the bellicose Tennessee militia general passionately desired, and of the invasion of Mexico which Burr would lead when hostilities began.808 At Lexington, at Frankfort, everywhere, Burr was received in similar fashion. While in Kentucky he met Henry Clay, who at once yielded to his fascination.

But soon strange, dark rumors, starting from Natchez, were sent flying over the route Burr had just traveled with such acclaim. They were set on foot by an American, one Stephen Minor, who was a paid spy of Spain.809 Burr, it was said, was about to raise the standard of revolution in the Western and Southern States. Daniel Clark wished to advise Burr of these reports and of the origin of them, but did not know where to reach him. So he hastened to write Wilkinson that Burr might be informed of the Spanish canard: "Kentucky, Tennessee, the State of Ohio, … with part of Georgia and Carolina, are to be bribed with the plunder of the Spanish countries west of us, to separate from the Union." And Clark added: "Amuse Mr. Burr with an account of it."810

Wilkinson himself had long contemplated the idea of dismembering the Nation; he had even sounded some of his officers upon that subject.811 As we have seen, he had been the leader of the secession movement in Kentucky in 1796. But if Burr ever really considered, as a practical matter, the separation of the Western country from the Union, his intimate contact with the people of that region had driven such a scheme from his mind and had renewed and strengthened his long-cherished wish to invade Mexico. For throughout his travels he had heard loud demands for the expulsion of Spanish rule from America; but never, except perhaps at New Orleans, a hint of secession. And if, during his journey, Burr so much as intimated to anybody the dismemberment of the Republic, no evidence of it ever has been produced.812

Ignorant of the sinister reports now on their way behind him, Burr reached the little frontier town of St. Louis early in September and again conferred with Wilkinson, assuring him that the whole South and West were impatient to attack the Spaniards, and that in a short time an army could be raised to invade Mexico.813 According to the story which the General told nearly two years afterward, Burr informed him that the South and West were ripe for secession, and that Wilkinson responded that Burr was sadly mistaken because "the Western people … are bigoted to Jefferson and democracy."814

Whatever the truth of this may be, it is certain that the rumors put forth by his fellow Spanish agent had shaken Wilkinson's nerve for proceeding further with the enterprise which he himself had suggested to Burr. Also, as we shall see, the avaricious General had begun to doubt the financial wisdom of giving up his profitable connection with the Spanish Government. At all events, he there and then began to lay plans to desert his associate. Accordingly, he gave Burr a letter of introduction to William Henry Harrison, Governor of Indiana Territory, in which he urged Harrison to have Burr sent to Congress from Indiana, since upon this "perhaps … the Union may much depend."815

Mythical accounts of Burr's doings and intentions had now sprung up in the East. The universally known wish of New England Federalist leaders for a division of the country, the common talk east of the Alleghanies that this was inevitable, the vivid memory of a like sentiment formerly prevailing in Kentucky, and the belief in the seaboard States that it still continued – all rendered probable, to those, living in that section, the schemes now attributed to Burr.

Of these tales the Eastern newspapers made sensations. A separate government, they said, was to be set up by Burr in the Western States; the public lands were to be taken over and divided among Burr's followers; bounties, in the form of broad acres, were to be offered as inducements for young men to leave the Atlantic section of the country for the land of promise toward the sunset; Burr's new government was to repudiate its share of the public debt; with the aid of British ships and gold Burr was to conquer Mexico and establish a vast empire by uniting that imperial domain to the revolutionized Western and Southern States.816 The Western press truthfully denied that any secession sentiment now existed among the pioneers.

The rumors from the South and West met those from the North and East midway; but Burr having departed for Washington, they subsided for the time being. The brushwood, however, had been gathered – to burst into a raging conflagration a year later, when lighted by the torch of Executive authority in the hands of Thomas Jefferson.

During these months the Spanish officials in Mexico and in the Floridas, who had long known of the hostility of American feeling toward them, learned of Burr's plan to seize the Spanish possessions, and magnified the accounts they received of the preparations he was making.817

The British Minister in Washington was also in spasms of nervous anxiety.818 When Burr reached the Capital he at once called on that slow-witted diplomat and repeated his overtures. But Pitt had died; the prospect of British financial assistance had ended;819 and Burr sent Dayton to the Spanish Minister with a weird tale820 in order to induce that diplomat to furnish money.

Almost at the same time the South American adventurer, Miranda, again arrived in America, his zeal more fiery than ever, for the "liberation" of Venezuela. He was welcomed by the Administration, and Secretary of State Madison gave him a dinner. Jefferson himself invited the revolutionist to dine at the Executive Mansion. Burr's hopes were strengthened, since he intended doing in Mexico precisely what Miranda was setting out to do in Venezuela.

In February, 1806, Miranda sailed from New York upon his Venezuelan undertaking. His openly avowed purpose of forcibly expelling the Spanish Government from that country had been explained to Jefferson and Madison by the revolutionist personally. Before his departure, the Spanish filibuster wrote to Madison, cautioning him to keep "in the deepest secret" the "important matters" which he (Miranda) had laid before him.821 The object of his expedition was a matter of public notoriety. In New York, in the full light of day, he had bought arms and provisions and had enlisted men for his enterprise.

Excepting for Burr's failure to secure funds from the British Government, events seemed propitious for the execution of his grand design. He had written to Blennerhassett a polite and suggestive letter, not inviting him, however, to engage in the adventure;822 the eager Irishman promptly responded, begging to be admitted as a partner in Burr's enterprises, and pledging the services of himself and his friends.823 Burr, to his surprise, was cordially received by Jefferson at the White House where he had a private conference of two hours with the President.

The West openly demanded war with Spain; the whole country was aroused; in the House, Randolph offered a resolution to declare hostilities; everywhere the President was denounced for weakness and delay.824 If only Jefferson would act – if only the people's earnest desire for war with Spain were granted – Burr could go forward. But the President would make no hostile move – instead, he proposed to buy the Floridas. Burr, lacking funds, thought for a moment of abandoning his plans against Mexico, and actually asked Jefferson for a diplomatic appointment, which was, of course, refused.825

The rumor had reached Spain that the Americans had actually begun war. On the other hand, the report now came to Washington that the Spaniards had invaded American soil. The Secretary of War ordered General Wilkinson to drive the Spaniards back. The demand for war throughout the country grew louder. If ever Burr's plan of Mexican conquest was to be carried out, the moment had come to strike the blow. His confederate, Wilkinson, in command of the American Army and in direct contact with the Spaniards, had only to act.

The swirl of intrigue continued. Burr tried to get the support of men disaffected toward the Administration. Among them were Commodore Truxtun, Commodore Stephen Decatur, and "General"826 William Eaton. Truxtun and Decatur were writhing under that shameful treatment by which each of these heroes had been separated, in effect removed, from the Navy. Eaton was cursing the Administration for deserting him in his African exploits, and even more for refusing to pay several thousand dollars which he claimed to have expended in his Barbary transactions.827

Truxtun and Burr were intimate friends, and the Commodore was fully told of the design to invade Mexico in the event of war with Spain; should that not come to pass, Burr advised Truxtun that he meant to settle lands he had arranged to purchase beyond the Mississippi. He tried to induce Truxtun to join him, suggesting that he would be put in command of a naval force to capture Havana, Vera Cruz, and Cartagena. When Burr "positively" informed him that the President was not a party to his enterprise, Truxtun declined to associate himself with it. Not an intimation did Burr give Truxtun of any purpose hostile to the United States. The two agreed in their contemptuous opinion of Jefferson and his Administration.828 To Commodore Decatur, Burr talked in similar fashion, using substantially the same language.

But to "General" Eaton, whom he had never before met, Burr unfolded plans more far-reaching and bloody, according to the Barbary hero's account of the revelations.829 At first Burr had made to Eaton the same statements he had detailed to Truxtun and Decatur, with the notable difference that he had assured Eaton that the proposed expedition was "under the authority of the general government." Notwithstanding his familiarity with intrigue, the suddenly guileless Eaton agreed to lead a division of the invading army under Wilkinson who, Burr assured him, would be "Chief in Command."

But after a while Eaton's sleeping perception was aroused. Becoming as sly as a detective, he resolved to "draw Burr out," and "listened with seeming acquiescence" while the villain "unveiled himself" by confidences which grew ever wilder and more irrational: Burr would establish an empire in Mexico and divide the Union; he even "meditated overthrowing the present Government" – if he could secure Truxtun, Decatur, and others, he "would turn Congress neck and heels out of doors, assassinate the President, seize the treasury and Navy; and declare himself the protector of an energetic government."

Eaton at last was "shocked" and "dropped the mask," declaring that the one word, "Usurper, would destroy" Burr. Thereupon Eaton went to Jefferson and urged the President to appoint Burr American Minister to some European government and thus get him out of the country, declaring that "if Burr were not in some way disposed of we should within eighteen months have an insurrection if not a revolution on the waters of the Mississippi." The President was not perturbed – he had too much confidence in the Western people, he said, "to admit an apprehension of that kind." But of the horrid details of the murderous and treasonable villain's plans, never a word said Eaton to Jefferson.830

However, the African hero did "detail the whole projects of Mr. Burr" to certain members of Congress.831 "They believed Col. Burr capable of anything – and agreed that the fellow ought to be hanged"; but they refused to be alarmed – Burr's schemes were "too chimerical and his circumstances too desperate to … merit of serious consideration."832 So for twelve long months Eaton said nothing more about Burr's proposed deviltry. During this time he continued alternately to belabor Congress and the Administration for the payment of the expenses of his Barbary exploits.833

Andrew Jackson, while entertaining Burr on his first Western journey, had become the most promising, in practical support, of all who avowed themselves ready to follow Burr's invading standard into Mexico; and with Jackson he had freely consulted about that adventure. From Washington, Burr now wrote the Tennessee leader of the beclouding of their mutually cherished prospects of war with Spain.

But hope of war was not dead, wrote Burr – indeed, Miranda's armed expedition "composed of American citizens, and openly fitted out in an American port," made it probable. Jackson ought to be attending to something more than his militia offices, Burr admonished him: "Your country is full of fine materials for an army, and I have often said a brigade could be raised in West Tennessee which would drive double their number of Frenchmen off the earth." From such men let Jackson make out and send to Burr "a list of officers from colonel down to ensign for one or two regiments, composed of fellows fit for business, and with whom you would trust your life and your honor." Burr himself would, "in case troops should be called for, recommend it to the Department of War"; he had "reason to believe that on such an occasion" that department would listen to his advice.834

At last Burr, oblivious to the danger that Eaton might disclose the deadly secrets which he had so imprudently confided to a dissipated stranger, resolved to act and set out on his fateful journey. Before doing so, he sent two copies of a cipher letter to Wilkinson. This was in answer to a letter which Burr had just received from Wilkinson, dated May 13, 1806, the contents of which never have been revealed. Burr chose, as the messenger to carry overland one of the copies, Samuel Swartwout, a youth then twenty-two years of age, and brother of Colonel John Swartwout whom Jefferson had removed from the office of United States Marshal for the District of New York largely because of the Colonel's lifelong friendship for Burr. The other copy was sent by sea to New Orleans by Dr. Justus Erich Bollmann.835

No thought had Burr that Wilkinson, his ancient army friend and the arch conspirator of the whole plot, would reveal his dispatch. He and Wilkinson were united too deeply in the adventure for that to be thinkable. Moreover, the imminence of war appeared to make it certain that when the General received Burr's cipher, the two men would be comrades in arms against Spain in a war which, it cannot be too often repeated, it was believed Wilkinson could bring on at any moment.

Nevertheless, Burr and Dayton had misgivings that the timorous General might not attack the Spaniards. They bolstered him up by hopeful letters, appealing to his cupidity, his ambition, his vanity, his fear. Dayton wrote that Jefferson was about to displace him and appoint another head of the army; let Wilkinson, therefore, precipitate hostilities – "You know the rest… Are you ready? Are your numerous associates ready? Wealth and glory! Louisiana and Mexico!"836

In his cipher dispatch to Wilkinson, Burr went to even greater lengths and with reason, for the impatient General had written him another letter, urging him to hurry: "I fancy Miranda has taken the bread out of your mouth; and I shall be ready for the grand expedition before you are."837 Burr then assured Wilkinson that he was not only ready but on his way, and tried to strengthen the resolution of the shifty General by falsehood. He told of tremendous aid secured in far-off Washington and New York, and intimated that England would help. He was coming himself with money and men, and details were given. Bombastic sentences – entirely unlike any language appearing in Burr's voluminous correspondence and papers – were well chosen for their effect on Wilkinson's vainglorious mind: "The gods invite us to glory and fortune; it remains to be seen whether we deserve the boon… Burr guarantees the result with his life and honor, with the lives and honor and the fortunes of hundreds, the best blood of our country."838

Fatal error! The sending of that dispatch was to give Wilkinson his opportunity to save himself by assuming the disguise of patriotism and of fealty to Jefferson, and, clad in these habiliments, to denounce his associates in the Mexican adventure as traitors to America. Soon, very soon, Wilkinson was to use Burr's letter in a fashion to bring his friend and many honest men to the very edge of execution – a fate from which only the fearlessness and penetrating mind of John Marshall was to save them.