полная версия

полная версияButterflies and Moths (British)

You need have but little difficulty in finding a willing worker, for such caterpillars are extremely numerous. Take a few out of their self-made homes, place them on a sprig of the food plant, and you will soon have the pleasure of seeing one start its extraordinary work.

At first it spins a number of threads stretching from the edge of a leaf to about the middle of the surface. These threads are not tight by any means, and the leaf is, as yet, unchanged in position. But now the little mechanic exhibits a tact that almost seems to prove a knowledge of the principles of its art. Each thread in turn is pulled at right angles at its middle, and then fastened by means of the creature's spinneret. Each time this is done the edge of the leaf is bent round a little; and when at last the cylinder is completed, a number of other threads are stretched across from the scroll to the flat part of the leaf to secure it firmly in its place.

Many caterpillars are solitary in their habits: that is, they are always found singly, whether walking, resting, or feeding. But a large number of species are gregarious, living in dense clusters either throughout their larval state or, perhaps, only while young. In many such cases it is difficult or even impossible to find any reason for this gregarious tendency – to discover any advantage that the insects may derive from the habit. Many species, however, are true co-operators in the defence of their communities. The caterpillars of such live in clusters, sometimes several scores in each, and all help in the spinning of a complicated mass of silk fibres, which, with the leaves and twigs they join together, form a safe home in which they can rest, feed, or change to the chrysalis state. In early summer hundreds of such caterpillar 'nests' are to be seen in many of our hawthorn and other hedgerows.

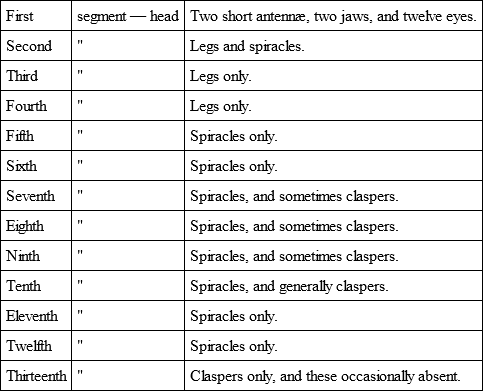

Before closing our general account of the caterpillar we must have a word to say about the breathing apparatus, more especially as in our future descriptions we shall frequently have to mention the colours and markings which surround the openings in its body through which the air supply is admitted.

If you examine the sides of the segments of a caterpillar, using a lens if the insect is a small one, you will observe some little round holes, often inclosed in a ring or a patch of some prominent colour. These are the spiracles or openings of a series of air tubes called tracheæ. These latter divide and subdivide within the body of the caterpillar, the branches of one often uniting with those of another, thus forming a really complicated arrangement of air pipes by which the supply of oxygen is distributed.

A microscopic examination of a portion of one of the tracheæ will show that its walls are supported by an elastic spiral of a firm substance. This arrangement serves to keep the air passages open, and secures for the caterpillar a free supply of air at times when a contraction of the segments would otherwise cause the tubes to collapse.

There are nine spiracles on each side of the caterpillar's body, and never more than one in the side of the same segment. The head, which we have been regarding as the first segment, has no spiracles. The second segment has a pair – one on each side. There are none in the third and fourth; but all the segments, from the fifth to the twelfth inclusive, have each a pair; the last (thirteenth) segment has none.

We have already observed the general arrangement of the caterpillar's limbs; but perhaps it may be interesting and even convenient to the reader to give here a little table that will show at a glance the disposition of both limbs and spiracles.

We must now watch the caterpillar through its later days, to see how it prepares for passing into the pupal stage, and to witness the various interesting changes that take place at this period.

When fully grown, it ceases to eat, and begins to wander about in search of a convenient spot for the coming event. Its colours fade, and the body becomes appreciably smaller, especially in length, as it ejects the whole contents of its digestive apparatus. According to some accounts, it even evacuates the lining of the intestines with their contents.

A great variety of situations are chosen by the different species at this time. Some will fix themselves on their own food plant, and there remain till they finally emerge in the perfect state, suspending themselves from a silken carpet, hiding themselves in a rolled leaf, or constructing a cocoon of some kind. A large number walk down the food plants, and undergo their changes in moss that happens to lie at the foot; or construct a cocoon on the surface of the ground, utilising for the purpose any decayed leaves, fragments of vegetable matter, or pieces of earth or small stones. Many seek a further protection than this, and burrow into the soil, where they either lie in a little oval cell that they prepare, or in a cocoon constructed by spinning together some particles of earth. Again, there are those caterpillars, chiefly of butterflies that frequent our gardens, which find their way to the nearest wall or fence, and there secure themselves in a sheltered nook. We will watch a few of these varied methods of procedure, taking as our first instance the caterpillar of the common Large White or Cabbage Butterfly.

When fully fed, this larva seeks out a sheltered spot, generally selecting the under surface of some object, or of the ledge of a wall or fence. Sometimes it will not even leave its food plant, though it generally walks some considerable distance before a suitable shelter is found. Having satisfied itself as to the site of the temporary abode, it sets to work at spinning a silken carpet. At first the threads spread over a rather wide area, and seem to be laid in a somewhat irregular and aimless manner; but after a little time its labours are concentrated on one small spot, where it spins several layers of silk fibres.

This done, it fixes the little hooks of the claspers firmly in its carpet bed, and then proceeds with a highly interesting movement. It is not satisfied with only the one mode of suspension. In fact, this alone would hardly be safe, for when it casts its skin, as it is shortly about to do, its claspers will all disappear; and although it afterwards secures itself by the 'tail,' it would be dangling in such a manner as to swing with every breeze – a very unsatisfactory state of affairs, especially with those that pupate late in the summer and remain in the pupal state throughout the winter storms.

Its next procedure, then, is to make a strong silk band round the middle of its body, so as to keep it close to the surface against which it rests. But how is this to be done? It bends its head round till the spinning organ can be applied to a point close beside the middle of its body. Here it fixes one end of a thread; and then, gradually twisting its body, brings its head round to the other side, still keeping it close to the same segment, and fastens the other end of the thread exactly opposite the point at which it started.

The head is now brought back to its former position, thus adding another thread to the band; and the process is repeated several times, till at last the caterpillar is satisfied with the thickness and strength of the cord formed.

Now it straightens out its body as if to rest from its labours; but the work is not yet complete. Soon it exhibits much restlessness. Its foremost segments are seen to shorten, and consequently become thicker. Then the skin splits, and the last moult of the caterpillar commences. The movements that follow are exactly similar to those we have already described in connection with one of the earlier moults: the alternate and successive contractions of all the segments gradually force back the old coat, and this is finally thrown entirely off by a somewhat vigorous wriggling of the 'tail.'

Then, for a moment, the creature is supported only by its silken cord. But this lasts only for a moment. For, as soon as it is quite free from the old garment, it applies its tail to the densest part of the carpet it had prepared at the start, and secures its hinder extremity by means of little hooks.

But what a change has now come over the creature! It is no longer a caterpillar. Its head is no longer distinct, although we can readily make out the positions of the eyes. Its mouth and jaws have quite disappeared, and the legs and claspers are apparently gone. The three segments that bore the legs are no longer distinctly separable, though in reality they still exist. The head and thorax are peculiarly shaped; and, instead of being cylindrical, are angled and ridged; but, beneath the soft greenish skin – the new garment – we can discern the outline of a pair of small wings, and see a proboscis and a pair of long antennæ. Also the six long legs of the future butterfly can be traced with care.

The abdomen is conical in form, coming to a sharp point at the end, and its segments are quite distinct.

No stranger to the metamorphoses of insects would connect the present form with that of a caterpillar; they are so very unlike. And yet the time occupied in the whole change, from the spinning of the carpet, does not occupy more than about thirty or thirty-five hours.

The apparent suddenness of this change is really surprising, but in reality the transformation is not nearly so sudden as it appears. Dissection of a caterpillar a few days before the final moult is due will show that the changes are already going on. In fact, a simple removal of the skin will prove that the organs of the future butterfly are developing. Still, in proportion to the short time occupied, the change is extremely great; and it may reasonably be inquired, Why so great a change within so short a space of time? – why is not the change continued steadily and equally through the larval existence? The reason has already been hinted at. Caterpillars are living eating machines, whose office is to remove excess of vegetable matter. Consequently they must have their jaws and bulky digestive apparatus in full development to the end. If these organs were to gradually disappear as the caterpillar reaches its non-eating stages, it would simply be starved to death. So the change from the larval to the pupal state, which we may regard as the final moult of the caterpillar, is a far greater change than any of the preceding ones, and occupies a proportionately longer time, although it is principally confined to the last few days of the caterpillar life.

A number of caterpillars, and especially those of the butterflies, suspend themselves when about to change; and the peculiarities of the modes adopted must be left for our descriptions of species in a future chapter; but we will find room here for one more interesting example, taking this time the larva of one of the commonest of the Vanessas (page 166) – the Small Tortoiseshell Butterfly.

The caterpillars of this insect are gregarious when young; and if ever you meet with one, you are almost sure to be able to obtain a hundred or so without much searching. But as they grow older they feed singly, yet generally without straying very far from their birthplace.

When full grown they sometimes stray to a neighbouring plant or fence to undergo the change to a chrysalis, but more commonly they are perfectly satisfied with the protection afforded by the leaves of their food plant. We will now watch one of these as we did the larva of the Large White Butterfly.

Of course the under side of the leaf is chosen. Here a silken carpet is spun as before described; but the caterpillar, instead of clinging with all its claspers, suspends itself in a vertical position by its hindermost pair only.

Here it hangs, head downwards, awaiting the coming events. The splitting and casting of the skin goes on just as in the case of the Large White, but there is this puzzle to be solved: how can the insect shuffle itself out of its old coat without falling to the ground, leaving the cast-off garments still hanging by the hooks of the claspers? This really seems a matter of impossibility, since the little hooks which alone suspend the insect are thrown off with the skin of the claspers.

The thing is managed in this way. As the skin slowly splits through the wrigglings of the apparently uncomfortable occupant, it is gradually pushed backward – that is, upward – till it is in a shrivelled condition, and the body of the insect is nearly free. But the chrysalis thus brought to light is provided with little hooks on the end of its 'tail' by which it can attach itself to the irregularities of the crumpled coat. Its conical abdomen is also very flexible, and it can, by bending this, seize hold of a ridge in the skin, holding it between the segments. Thus, although practically quite free from the old garb, it never falls to the ground.

There is now, however, another point to be attended to. The newly formed chrysalis desires to be entirely independent of its cast-off skin, and to suspend itself directly from the silky carpet it has prepared. To this end it works steadily for a time, alternately bending its supple abdomen from side to side, gripping the folds of the skin between the segments, pulling its body a little higher at each movement, and securing itself at each step by the little hooks at its extremity.

So it climbs, and at last it reaches the network of silk fibres, and thrusts the tip of its abdomen among them till some of the hooks have taken hold. Not satisfied with this, it turns its body round and round to get the little hooks so entangled between the silk fibres that a fall is impossible, and in so doing it frequently pushes the old skin out of its place so that it falls to the ground.

Although the caterpillars of this species do not show any great gregarious tendency when nearly full fed, yet it is not an uncommon thing to find several hanging from the under surface of one leaf, all being attached to the one common carpet at which all had worked. And when bred in confinement, a number will often spin in company in a corner of their cage. I have thus obtained a cluster of thirty-seven pupæ, all hanging by the 'tails' to the same mass of silk, which was so small that they formed quite a compact mass of beings with their tails close together.

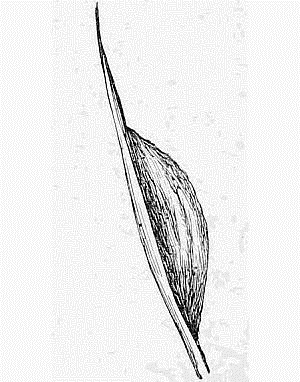

Fig. 28. – The Cocoon of the Emperor Moth.

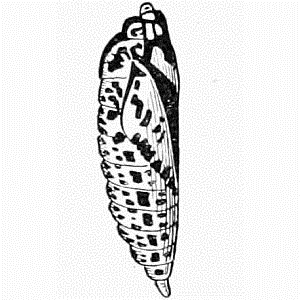

Fig. 29. – The Cocoon of the Six-spotted Burnet (Filipendulæ).

We have seen that the Large White Butterfly makes itself secure by a silk band round its middle, while the 'Tortoiseshell' is fixed only by its tail. But the extra provision for the safety of the former is not so necessary in the case of the latter, as it never spends more than two or three weeks in the pupal state. Here it is the perfect insect that braves the winter, and not the chrysalis.

There is a great variety in the means taken by the caterpillars of moths to protect themselves during their metamorphoses, but we shall have space for only a few illustrations.

A clever cocoon is spun by the larva of the Emperor Moth (Pavonia). It is pear-shaped, and composed of a brownish silk; and is so constructed that the newly emerged moth can easily walk out of the small end without breaking a fibre, while the entry of an insect enemy from without is impossible.

This is managed as follows. A number of rather stiff threads are made to project from the small end of the cocoon, and these converge as they pass outward so that the ends are all near together. The other portions of the cocoon are of compact silk, and any insect intruder that ventures to enter by what we may almost term the open end is met by a number of spikes, as it were, that play on it at every attempt. Many of these wonderful cocoons may be found during the winter months attached to the food plants of this insect.

Of the silken cocoons spun by various caterpillars some are so thin and light that the chrysalis can easily be seen through them, and others are so densely woven as to be quite opaque. A great difference is also to be observed in the adhesive power of the silk fibres. In some cases little threads of silk can be pulled off the cocoon; but some of them, that of the Oak Eggar (page 229) for example, look as if they had been constructed of paper rather than of silk, because, at the time of spinning, the moist silk fibres stuck so closely together.

An extreme case of this character is to be met with in the cocoon of the Puss Moth (page 235); for here the fluid from the spinneret of the caterpillar does not harden at once on exposure to air, and so the threads become thoroughly united together, thus forming a solid gluey cocoon.

When the Puss caterpillar is about to change, it descends the tree (poplar, willow, or sallow) till it is within a few feet of the ground. Then it commences gnawing away at the bark, at the same time cementing all the pieces together with the gluey substance from its spinning glands. In this way it surrounds itself with a very hard cocoon, which so closely resembles the surrounding bark in colour that detection is difficult indeed.

But how will the caterpillar proceed if it is removed from its native tree and has no bark to gnaw? That you can easily answer for yourself, or rather Puss will answer it for you. Go and search among the poplars, willows and sallows in the month of July. You may possibly come across a caterpillar that is just in the act of creeping down the bark in search of a resting place; but if not you may be successful in obtaining a few either by examining the twigs, or you may start them from their hiding places by smartly tapping the smaller branches with a strong stick.

Having secured one or more larvæ, take them home, and they will give some rather novel performances. If they are not fully grown, you must supply them with fresh leaves every day till they refuse to eat; and then is the time for your experiments. Shut one in a little wooden box, and you will have the pleasure of watching it construct a cocoon of chips of wood that it has bitten out with its powerful jaws, all joined together into a hard shell by means of transparent glue. Shut another Puss in a glass vessel – a tumbler, for instance – either by placing it under the inverted vessel, or by covering over the top. Perhaps it will not be superfluous to mention that, should you place it under an inverted vessel, this vessel should not stand on a polished table, for, whatever be the material, unless extremely hard, it is sure to be utilised in the manufacture of the cocoon.

Let us suppose, then, that the caterpillar is under an inverted tumbler that stands on a plate or saucer. Now it is for you to decide what material shall be used in the construction of the new home. Give Puss some fine strips of brightly coloured ribbon, and it will construct a very gaudy house by gluing them together. Or, provide it with sawdust, pieces of rag, glass beads, sand, paper, anything in fact; and the material will be 'made up' into a cocoon more or less ornamental according to the nature of the supply.

But what if you give it nothing with which to work, and so inclose it that nothing its jaws can pierce is within its reach? For instance, shut it in with tumbler and saucer as before, inverting the former on the latter, and give it no material whatever. What will it do now? We will watch and see.

At first it is very restless, and walks round and round the edge of the tumbler, evidently a little dissatisfied with the prospects. Then, after a little while, the events of nature transpiring in their fixed order regardless of trivial mishaps, the glutinous fluid begins to flow from the creature's spinning glands, and it moves about in a somewhat aimless fashion, applying the transparent adhesive matter both to tumbler and saucer.

It seems now to become a little more reconciled to its unnatural surroundings; and, making the best of bad matters, keeps its body in one place, and starts the construction of a ridge or barrier all round itself. By the continued application of the creature's spinneret this barrier is made gradually thicker and higher, till at last the overhanging sides meet and the caterpillar is inclosed in its self-constructed prison. But the walls of this prison are so transparent that every movement can be watched; and, after the insect has spent a few days in completing the cocoon, we can see it cast off its old skin, and appear in the new garb of a fine greenish chrysalis.

Its soft green skin soon hardens and turns to a rich dark brown colour, and it settles down for a long rest lasting till the following May or June.

When the whole operation of building is completed, lift up the tumbler, and up will come the saucer too. The two are firmly glued together by the substance secreted; and the power of this as a cementing material will be well illustrated if you endeavour by mere pulling force to separate the two articles.

The Puss is not the only caterpillar that works up a foreign material with the contents of the spinning organs. There are several others, in fact, that use for this purpose fragments of wood or other parts of the food plants; and a still larger number bind together leaves, fresh or dead, or particles of earth or other matter. Several such cocoons will be described in our accounts of individual species in another chapter. We shall now devote a little space to a few general remarks on the chrysalides and the final metamorphosis of butterflies and moths.

CHAPTER IV

THE PUPA OR CHRYSALIS

As soon as the last moult of the caterpillar is over, the chrysalis that had already been developing under the cover of the old skin is exposed to full view; and although the perfect insect is not to be liberated for some time to come, yet some of its parts are apparently fully formed.

Fig. 30. – The Pupa of the Privet Hawk (Ligustri).

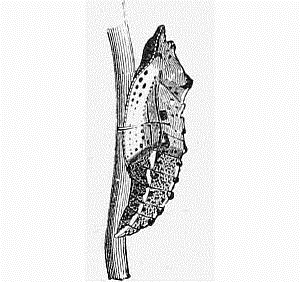

Fig. 31. – The Chrysalis of the Large White Butterfly (Brassicæ).

The newly exposed skin of the chrysalis is very soft and moist, but as it hardens it forms a membranous or horny covering that protects and holds firmly in place the trunk and the various limbs and appendages that are distinctly to be traced on the under surface.

If, however, you examine a chrysalis directly after the moult is over, you will often find that the wings, antennæ, proboscis, and legs of the future butterfly can be easily separated from the trunk of the body on which they lie by means of a blunt needle, and can be spread out so as to be quite free from that surface.

In form the chrysalides of butterflies and moths are as variable as the caterpillars. Many of the former are sharply angular like that of the 'Small Tortoiseshell' already mentioned; but some of the butterflies – the Skippers (page 197) – have smooth and tapering chrysalides, and so have most of the moths.

In colour they are equally variable. Some are beautifully tinted with delicate shades of green, some spotted on a light ground, some striped with bands more or less gaudy and distinct, but the prevailing tint, especially among the moths, is a reddish brown, often so deep that it is almost a black.

Fig. 32. – The Pupa of the Dark Green Fritillary (Aglaia).

Fig. 33. – The Pupa of the Black-veined White Butterfly (Cratægi).

As a rule there is no marked resemblance between the different stages of the same insect. Thus, a brilliantly coloured caterpillar may change to a dull and unattractive chrysalis, from which may emerge a butterfly or moth that partakes of the colours of neither. But in a few cases there are colours or other features that remain persistent throughout the three stages, or show themselves prominently in two.