полная версия

полная версияButterflies and Moths (British)

What a marvellously acute sense this must be, that thus enables the insects to scent out, as it were, their mates at considerable distances, even when doubly surrounded by a wooden box and the material of a coat pocket! You would naturally expect that entomologists have turned this wonderful power to account. Many a box has been filled with the beautiful Kentish Glories of the male kind, who had been led into the snare by the attractions of a virgin Glory that they were never to behold. Many an Emperor has also been decoyed from his throne to the place of his execution, beguiled by the imaginary charms of an Empress on whom he was never to cast one passing glance. And these and other similar captures have been made in places where, without the employment of the innocent enchantress, perhaps not a single male could have been found, even after the most diligent search.

Speaking of this surprising sense, I am again tempted to revert to the antennæ; for it is a remarkable fact that the males of those species of moths which exhibit the power of thus searching out their mates, are just those that are also remarkable for their very broad and deeply pectinated antennæ – a fact that has led to the supposition that the power in question is located in the antennæ, and is also proportional to the amount of surface displayed by these organs.

Up to the present time we have been considering the butterfly and moth in their perfect forms, but everybody knows that the former is not always a butterfly, nor is the latter always a moth; but that they both pass through certain preparatory stages before they attain their final winged state.

We shall now notice briefly what these earlier stages are, leaving the detailed descriptions of each for the following chapters.

The life of the perfect butterfly or moth is of very short duration, often only a few days, nearly the whole of its existence having been spent in preparing itself for the brief term to be enjoyed

… in fields of light,And where the flowers of Paradise unfold.It may be interesting to consider of what use the metamorphoses of insects are, and to what extent these metamorphoses render them fit for the work they have to do.

It is certain that the chief work of insects, taken as a whole, is to remove from the earth the excess of animal and vegetable matter. If they are to do this work effectually, it is clear that they must be very voracious feeders, and also be capable of multiplying their species prodigiously. Now each of these powers requires the special development of a certain set of organs, and an abnormal development of one set must necessarily be produced at the expense of the other. Hence we find insects existing in two distinct stages, with or without an intermediate quiescent state, during the first of which the digestive apparatus is enormously developed, while the reproductive organs occupy but very little space; then, during the other stage, the digestive apparatus is of the simplest possible description, and the organs of reproduction are in a perfect state of development.

Allowing, then, that the chief work of the insect is the removal of surplus organic matter, we can see that a large share of its life should be spent in the larval or grub stage, and that the perfect state need not occupy any more time than is necessary for the fertilisation of the eggs that almost completely fill the body of the female at the time of her emergence from the chrysalis shell.

Many insects undergo their metamorphoses by slow degrees, but the Lepidoptera, after existing for some considerable period without any important visible change in structure, pass by a rapid transition into the next state. Thus, a caterpillar, that has not altered in general form for several weeks, changes into a chrysalis within the course of a few days; and again, after a period of quiescence that may extend throughout the whole of the colder months, becomes a perfect butterfly or moth within twenty minutes of the moment of its emergence.

But this suddenness is more apparent than real, as may easily be proved by internal examinations of the insect at various stages of growth; showing that we are led astray by the rapidity of external changes – the mere moultings or castings of the skin – while the gradual transformations proceeding within are not so readily observed.

We have already said that the life of the perfect butterfly or moth is short. A few days after emergence from the chrysalis case, the female deposits her eggs on the leaves or stems of the plant that is to sustain the larvæ. Her work is now accomplished, and the few days more allowed her are spent in frolicking among the flowers, and sucking the sweet juices they provide. But males and females alike – bedecked with the most gorgeous colours and overflowing with sportive mirth when first they take to the wing – soon show the symptoms of a fast approaching end. Their colours begin to fade, and the beauty-making scales of the wings gradually disappear through friction against the petals of hundreds of flowers visited and the merry dances with scores and scores of playful companions. At last, one bright afternoon, while the sun is still high in the heavens, a butterfly, more weary than usual, with heavy and laborious flight, seeks a place of rest for the approaching night. Here, on a waving stalk, it is soon lulled to sleep by a gentle breeze.

Next morning, a few hours before noon, the blazing sun calls it out for its usual frolics. But its body now seems too heavy to be supported by the feeble and ragged wings, and, after one or two weak attempts at play, incited by the approach of a younger and merrier companion, it settles down in its final resting place. On the following morning a dead butterfly is seen, still clinging by its claws to a swinging stem, from which it is eventually thrown during a storm.

The tale of the perfect moth is very similar to the above, except that it is generally summoned to activity by the approach of darkness.

We see, then, that butterflies and moths exhibit none of that quality which we term parental affection. Their duty ends with the deposition of the eggs, and the parents are dead before the young larvæ have penetrated the shell that surrounds them.

Yet it is wonderful to see how unmistakably the females generally lay their eggs on the very plants that provide the necessary food for their progeny, as if they were not only conscious of and careful concerning the exact requirements of their offspring, but also possessed such a knowledge of botanical science as enabled them to discriminate between the plant required and all others.

Has the perfect insect any selfish motive in this apparently careful selection of a plant on which to lay its eggs? Does the female herself derive any benefit from the particular plant chosen for this purpose? In most cases, certainly not. For it often happens that the blossom of this plant is not by any means one of those that supply the sweets which insects love, and still more frequently does it occur that the eggs are deposited either before the flowers have appeared or after they have faded.

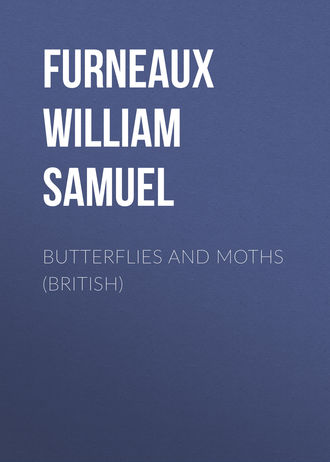

Fig. 10. – The Four Stages of the Large White Butterfly (Pieris Brassicæ).

a, larva; b, pupa; c, imago; d, egg.

Neither can we easily impute to the insect an acquired knowledge of the nature and wants of her offspring, or an acquaintance with botany sufficient to enable her to distinguish plant forms. Our only solution of the problem (which is really no solution at all) is to attribute the whole thing to that inexplicable quality which we are pleased to term natural instinct. It is to be observed, however, that it is not all butterflies and moths that display this unerring power. Some few seem to deposit their eggs indiscriminately on all kinds of herbage. But, I believe, the larvæ of these species are generally grass feeders, and would seldom have to travel far from any spot without meeting with an acceptable morsel.

But we must now pass on to a brief consideration of the other stages of the insect's existence. After a time, varying from a few days to several months, the young caterpillars or larvæ make their appearance. They soon commence feeding in right earnest. Their period of existence in this state varies from a few weeks to several months, and even, in some cases, to years. During this time their growth is generally very rapid, and they undergo a series of moults or changes of skin, of which we shall have more to say in a future chapter. Then, when fully grown, they prepare for an apparently quiescent form, which we speak of as the pupa or chrysalis, and in which they again spend a very variable period, extending over a few days, weeks, or months. Now, inclosed in a protective case, each pupa is undergoing a remarkable change. Some of its old organs are disappearing, and others are developing; and, after all the parts of the future insect have been developed as far as its narrow shell will permit, it bursts forth into the world as a perfect insect or imago.

Its wings at first are small, shapeless, and crumpled in a most unsightly fashion; but it is not long before they assume their full size, beautiful form, and gorgeous colouring. Then, in about another hour or two, the wings, at first soft and flaccid, have become sufficiently dry and stiff to bear their owner rapidly through the air.

We have thus observed some of the more striking features in the structure of the butterfly and moth in its most perfect state; and alluded in a very brief manner to the various stages through which these creatures must necessarily pass before finally reaching this stage. But now we must study these earlier stages more closely, and watch the insects during the marvellous transitions they are destined to undergo. This we shall do in the following chapters.

CHAPTER II

THE EGG

I suppose you are all acquainted with the general structure of the hen's egg, having dissected several, in your own way, many a time.

Its outer covering, which you speak of as the 'shell,' you have observed is hard and brittle. It is composed of a calcareous or limy substance, known chemically as carbonate of lime. If you put some pieces of it into an egg cup, and throw over them a little vinegar or any other liquid acid, you will see them gradually dissolve away, and small bubbles of carbonic acid gas will rise into the air. Then again, if you take a long and narrow strip of the shell, and hold one end of it in a gas or lamp flame, after a short time that end will become softer, and will glow brightly in the flame, for it is converted into lime – the same substance that is used by the builders for making their mortar – and the bright glow is really a miniature lime light, such as is always produced when a piece of lime is made intensely hot.

Just inside this shell you have seen a thin membrane or skin that is easily peeled off the substance of the egg itself. Next to this comes the 'white' of the egg, which is really colourless while liquid, but turns white and more or less solid in the cooking. Last of all, in the centre of this, you have noticed the oval yellow mass that is termed the 'yoke' or 'yolk,' and which contains the embryo of the future chick.

Now if you imagine this egg to be reduced in size till two or three dozen of them would be required to form a single line about one inch long, the outer calcareous shell to be entirely removed, the skin or membrane to be converted into a firmer substance of a horny nature, and, finally, the yolk to be absent and the whole internal space to be filled with the 'white,' you will then have some idea of the nature of the egg of a butterfly or moth.

To put the matter more briefly, then, we will say that the eggs of these insects are simply little liquid masses, usually of a colourless substance, surrounded by a horny and flexible covering.

Such a description may certainly give you some idea of the nature of the eggs of insects, but no amount of book reading will serve the purpose so well or be so pleasant as the examination of the eggs themselves. During the summer months very little difficulty will be experienced in finding some eggs in your own garden. Turn over some leaves and examine their under surfaces, choosing especially those plants which show, by their partially eaten leaves, that they are favourites with the insect world. Or you may amuse yourself by catching a number of butterflies – common 'Whites' are as good for the purpose as any – and temporarily confine them in a wooden or cardboard box, containing a number of leaves from various plants, and covered with gauze. In this way you are sure to obtain a few females that have not yet laid all their eggs; and if you watch your prisoners you will soon see them carefully depositing the eggs on the under surfaces of leaves, bending their abdomens round the edges if there is not sufficient room to get themselves completely under. And then, when you are satisfied with the number of eggs thus obtained for your examination, you can have the pleasure of seeing all your liberated captives flying joyfully in the free air.

In giving these simple instructions I have assumed that the reader has not yet learnt any of the characters by which female butterflies are to be distinguished from their lords and masters; but I hope that he will know soon, at least with regard to a good many species, from which individuals he may most reasonably expect to obtain eggs, and so be able to avoid the imprisonment, even though only temporary, of insects which cannot satisfy his wants.

Again, it is not necessary, after all, that butterflies should be captured for the purpose of obtaining eggs. Watch them as they hover about among your flowers. Some, you will observe, are intent on nothing but idle frolicking; and you may conclude at once that these have no immediate duty to perform. Others are flying without hesitation from flower to flower, gorging themselves with the sweets of life: these are not the objects of your search. But you will descry certain others, flying round about the beds and borders with a steadier and more matronly air, taking little or no notice of their more frivolous companions, and paying not the slightest heed to the bright nectar-producing cups of the numerous flowers. These are seriously engaged with family affairs only. Watch one of them carefully, and as soon as she has settled herself on a leaf, walk steadily towards her till you are near enough to observe her movements. She will not move unless you approach too closely, for, like busy folk generally, she has no time to worry about petty annoyances. You will now actually witness the deposition of the eggs exactly as carried on in the perfect freedom of nature; and the eggs themselves may be taken either for examination or for the rearing of the caterpillars.

Some species of Lepidoptera lay some hundreds of eggs, and it is seldom that the number laid by one female is much below a hundred.

As already stated, the under surfaces of leaves are generally chosen for the deposit of eggs, but a few of the insects we are considering always select the upper surface for this purpose. Thus the Puss Moth (page 235), and two or three others resembling it, though much smaller, known as the Kittens (page 234), invariably lay them on the upper surface. And this is the more surprising since the eggs of these moths are brown or black, and consequently so conspicuous on the green leaves as to be in danger of being sighted by the numerous enemies of insects.

The Hairstreak Butterflies (page 183) afford another exception to the general rule, for their eggs are deposited on the bark of the trees and shrubs (birch, sloe, elm, oak, and bramble) on which their larvæ feed.

At the moment each egg is laid it is covered with a liquid sticky substance, so that it is immediately glued to the leaf or stem as soon as it is deposited. The sticky substance soon dries, causing the egg to be so firmly fastened in its place that it is often impossible to force it off without destroying it completely.

Some of the Lepidoptera deposit their eggs singly, or in small irregular clusters; but by far the larger number set them very regularly side by side, in so compact a mass that it would be impossible to place them on a smaller area without piling one on top of another. This is not accomplished with the aid of the sight, for the insect performing her task with such precision often has her head on one side of a leaf or stem while arranging her eggs on the other. If you take the trouble to watch her, you will see that she carefully feels out a place for each egg by means of the tip of her abdomen immediately before laying it.

The eggs are laid by moths and butterflies at various seasons of the year. In some cases they are deposited early in the spring, even before the buds of the food plants have burst; and the young larvæ, hatched a few weeks later, commence to feed on the young and tender leaves. Then, throughout the late spring, the whole of the summer and autumn, and even till the winter frosts set in, the eggs of various species are being laid.

Those deposited during the warm weather are often hatched in a few days, but those laid toward the autumn remain unchanged until the following spring.

In this latter case the frosts of the most severe winter are not capable of destroying the vitality of the eggs. In many instances the perfect insect or the larva would be killed by the temperature of an average winter day, but the vitality of the eggs is such that they have been subjected to a temperature, artificially produced, of fifty degrees below the freezing point, and even after this the young larvæ walked out of their cradles at their appointed time just as if nothing unusual had occurred.

Experiments have also been performed on the eggs with a view of determining how far their vitality is influenced by high temperatures. We know that the scorching midsummer sun has no destructive influence on them, but these experiments prove that they are not influenced by a temperature only twenty degrees below the boiling point – actually a considerably higher temperature than is necessary to properly cook a hen's egg.

Let us now examine a number of eggs of different species, that we may note some of the many variations in form and colour.

With regard to colour, we have already observed that the eggs of a few species are black; but more commonly they are much lighter – pearly white, green, yellow, and grey being of frequent occurrence.

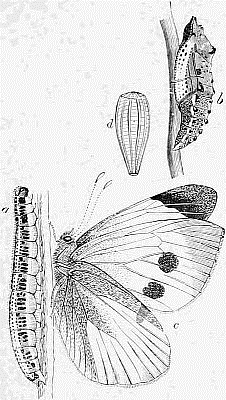

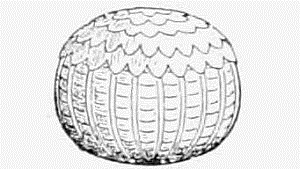

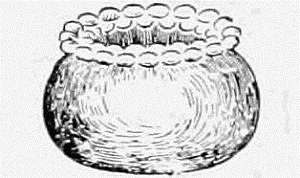

The great variety of form, however, will provide a vast amount of enjoyment to anyone who possesses a good magnifying lens or a small compound microscope. Some are globular, others oval; while many others represent cups, basins, and domes. Then we have miniature vases, flasks, bottles with short necks, and numerous figures that must remind a juvenile admirer of the sweet cakes and ornamental jellies that have so often gladdened his longing eyes.

Again, the beautifully sculptured surfaces of a large number are even more striking than their general shapes. Some are regularly ribbed from top to bottom with parallel or radiating ridges, and at the same time marked with delicate transverse lines. Others are beautifully pitted or honeycombed, some ornamented with the most faithful representation of fine wicker-work, while a few are provided with a cap, more or less ornamental, that is raised by the young larva when about to see the world for the first time. A few of these beautiful forms are here illustrated and named, and another has already appeared on page 14, but an enthusiastic young naturalist may easily secure a variety of others for his own examination.

Fig. 11. – Egg of the Meadow Brown Butterfly.

Fig. 12. – Egg of the Speckled Wood Butterfly.

Fig. 13. – Egg of the Vapourer Moth.

It may be surmised from the accompanying illustrations that the form of the egg is always the same for any one species. This is really the case, and consequently an experienced entomologist can often decide on the name of the butterfly or moth that deposited a cluster of eggs he happens to find in his rambles and searchings; but in such decisions he is always greatly assisted by a knowledge of the food plants of the various insects, and sometimes also by the manner in which the eggs are arranged.

We have seen that the period during which the Lepidoptera remain in the egg stage is very variable, and depends largely on the season in which they were laid; but it is often possible to tell when to expect the young larvæ by certain changes which take place in the appearance of the egg. As the horny covering of the egg is transparent, the gradual development of the caterpillar from the clear fluid can be watched to a certain extent; but if you have a microscope, and would like to witness this development to perfection, proceed as follows.

Arrange that some butterflies and moths shall lay their eggs on strips of glass of convenient dimensions for microscopic work – three inches long by one wide is the usual size for this kind of work. This is easily accomplished by placing a proper selection of female insects in a rather small box temporarily lined with such 'slips.' When a few eggs have thus been secured, all you have to do is to examine them at intervals with your microscope, always using the reflector so as to direct a strong light through the eggs from below.

But even without such an arrangement some interesting changes are to be observed. As a rule, the colour of the egg turns darker as the time for the arrival of the infant larva approaches, and you will often be able to see a little brown or black head moving slightly within the 'shell.' You may know then that the hatching is close at hand, and the movements of the tiny creature are well worth careful watching. Soon a small hole appears in the side of the case, and a little green or dark cap begins to show itself. Then, with a magnifier of some kind, you may see a pair of tiny jaws, working horizontally, and not with an up-and-down motion like our own, gradually gnawing away at the cradle, till at last the little creature is perfectly free to ramble in search of food.

Strange to say, the young larva does not waste a particle of the horny substance that must necessarily be removed in securing its liberty, but devours it with an apparent relish. Indeed, it appreciates the flavour of this viand so highly that it often disposes of the whole of its little home, with the exception of the small circular patch by which it was cemented to the plant. When the whole brood have thus dispensed with their empty cradles, there remains on the stem or leaf a glittering patch of little pearly plates.

After the performance of this feat the young caterpillar starts off in life on its own account with as much briskness and confidence as if it had previously spent a term in the world under the same conditions; but we must reserve an account of its doings and sufferings for our next chapter.

CHAPTER III

THE LARVA

In almost every case the young caterpillar, on quitting the 'shell' of the egg, finds itself standing on and surrounded by its natural food, and immediately commences to do justice to the abundant supply. It will either nibble away at the surface of the leaf, removing the soft cellular substance, so that the leaf exhibits a number of semi-transparent patches when held up to the light, or it will make straight for the edge, and, closing its horizontal jaws on either side, bite the leaf completely through, and thus remove a small piece each time.

Fig. 14. – The Caterpillar of the Clouded Yellow Butterfly.

Several naturalists have amused themselves by performing experiments and making calculations on the efficiency of the masticating and digesting powers of the caterpillar. The illustrious Réaumur, for example, proved that some of the cabbage eaters disposed of more than twice their own weight of food in twenty-four hours, during which time their weight increased one-tenth. Let us see what this would be equivalent to in human beings: A man weighing eleven stone would devour over three hundred pounds of food in a day, and at the end of that day weigh about fifteen pounds more than he did at the beginning!