полная версия

полная версияButterflies and Moths (British)

The front of the larva is generally the last portion to become dry, and when this is quite rigid the skin may be removed from the blowpipe. This is a matter that requires the greatest care; for the skin is so very thin and brittle that a little rough handling will break it to pieces. As a rule it may be easily pushed off the pipe by a slight pressure behind, or a gentle twisting motion will loosen its hold; but this latter method can hardly be applied to hairy larvæ without breaking off the hairs, now rendered very brittle by the heat.

If you find the slightest difficulty in detaching the skin of a valuable specimen, it is far better to damage the blowpipe than to risk spoiling the skin. Supposing your blowpipe is a glass one, you can easily break off the end of it after making a cut with a very small triangular file, and the portion thus removed may be left attached to the skin. Then, after softening the glass blowpipe in a gas flame or the flame of a spirit lamp, it can be drawn out thin again for future work. Those who can manipulate glass tubing in this way will find it far better to lay in a stock of suitable material, drawing it out when required, than to purchase blowpipes ready made at the naturalist's shop.

Very fine hollow stems, such as those of the bamboo cane, may be used instead of glass; and these possess the advantage of being easily cut with a sharp knife when there is any difficulty in removing the skin. Again, whether glass or fine stems are used, a little grease of any kind placed previously on the end will allow the dried skin to be slid off with less difficulty.

Preserved larvæ should preferably be mounted on small twigs or artificial imitations of the leaves of the proper food plants. A little coaguline applied to the claspers will fix them very firmly on these twigs or leaves, which are then secured in the cabinet by means of one or two small pins.

It is much to be regretted that the natural colours of many caterpillars cannot be preserved in the blown skins. Some are rendered much lighter in colour on account of the withdrawal of the contents, while others turn dark during the drying. In the smooth-skinned species the natural tints may be restored by painting or by staining with suitable aniline dyes, but these artificial imitations of the natural colours are always far less beautiful than the hues of the living larvæ.

Very few words need be said on the preservation of pupæ. Many of them do not alter much in form and colour, and therefore they require no special preparation.

If a pupa has to be killed for the purpose of adding to the value of the collection, simply plunge it into boiling water, and it is ready to be fixed in the cabinet as soon as it is quite dry.

The empty pupa cases, too, from which the perfect insects have emerged, are often worth preserving, especially if the damage done by the imago on forcing its way out is repaired with the aid of a little coaguline.

Let all larvæ and pupæ be preserved in their characteristic attitudes and positions as far as possible, so that each one tells some interesting feature of the life history of the living being it represents. Further, enrich your collection by numerous specimens of the various kinds of cocoons constructed by the larvæ, pinning each one beside its proper species; and never refuse a place to any object that relates something of the life history of the creatures you are studying.

CHAPTER XI

THE CABINET—ARRANGEMENT OF SPECIMENS

The selection of a cabinet or other storehouse for the rapidly increasing specimens of insect forms is often a matter of no small difficulty to a youthful entomologist. Indeed, there are very many points of considerable importance to be considered before any final decision is made. Freedom from dust, the exclusion of pests, the convenience of the collector, the depth of his pocket, and the general appearance of the storehouse must be considered, and it is impossible, therefore, to describe a form that is equally suitable to all.

If it is absolutely necessary that the cabinet (or its substitute) be of a very inexpensive character, and if, at the same time, the collector has not the mechanical skill necessary for its construction, then perhaps the best thing he can do is to procure a number of shallow (about an inch and a half deep) cardboard, glass-topped boxes, such as are to be obtained at drapers' shops. For the sake of uniformity and convenience in packing, have them all of one size. Glue in small slices of cork just where the insects are to be pinned, and see that each box is supplied with either camphor or naphthaline. All the boxes may be packed in a cupboard or in a case made specially to contain them; and a label on the front of each will enable you to select any one when required without disturbing the others.

It may be mentioned here that glass is not necessary, though it is certainly convenient at times, especially when you are exhibiting your specimens to admiring non-entomological friends, who have almost always a most alarming way of bringing the tip of the first finger dangerously near as they are pointing out their favourite colours. 'Isn't that one a beauty?' is a common remark, and therewith off snaps a wing of one of your choicest insects. When glass is used, however, see that the specimens are excluded from light, or the colours will soon lose their natural brilliancy.

Anyone who has a set of carpenter's tools and the ability to use them well will be able to construct for himself either a set of store boxes or a cabinet of many drawers in which to keep his natural treasures. In this case a few considerations are necessary before deciding on the form which the storehouse is to take.

A cabinet, if nicely made, forms a very sightly article of furniture; and, if space can be found for it, is the best and most convenient receptacle. One of about twelve to twenty drawers will be quite sufficient for a time; and the few following hints and suggestions may be useful.

The wood used should be well seasoned, and free from resin. The drawers should fit well, and slide without the least danger of shaking. Each one should be lined with sheet cork, about one-eighth of an inch thick, glued to the bottom, nicely levelled with sand paper, and then covered with thin, pure white paper, laid on with thin paste. It is also advisable to cover each with glass, inclosed in a light wood frame that fits so closely as to prevent the intrusion of mites.

The drawers may be arranged in a single vertical tier if the cabinet is to stand on the floor, or in two tiers if it is to be shorter for placing on the top of another piece of furniture; and glass doors, fastened by a lock and key, may be made to cover the front if such are desired as a matter of fancy, or as a precaution against the meddlesome habits of juvenile fingers.

Store boxes are sometimes chosen in preference to cabinets because they are more portable, and because they can be arranged on shelves – an important consideration when floor space is not available.

These boxes should be cork-lined and glazed like the cabinet drawers; and if they are made in two equal portions, lined with cork on both sides, and closing up like a book, they may be arranged on shelves like books, in which position they will collect but little dust.

Both store boxes and cabinets are always kept in stock by the dealers, the former ranging from a few shillings each, and the latter from fifteen shillings to a guinea per drawer. Knowing this, you can decide for yourself between the two alternatives – making and purchasing.

We have now to consider the manner in which our specimens should be arranged and labelled.

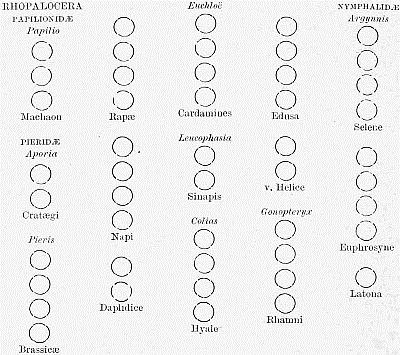

The table forming Appendix I contains the names of all the British butterflies and larger moths, and shows their division into Sections, Tribes, Families, and Genera. This table is the result of most careful study on the part of leading entomologists, and shows how, in their opinion, the insects can best be arranged to show their relation to one another; and you cannot do better than adopt the same order in your collection.

Complete label lists can be purchased, printed on one side of the paper only. These, when cut up, supply you with neat labels for your specimens.

If you intend to study the British Lepidoptera as completely as possible, you may as well start at once with a sufficiently extensive cabinet, and arrange all the labels of your list before you introduce the insects. You will thus have a place provided ready for each specimen as you acquire it, and the introduction of species obtained later on will not compel you to be continually moving and rearranging the drawers.

Probably the number of blank spaces will at first suggest an almost hopeless task, but a few years of careful searching and rearing will give you heart to continue your interesting work.

Arrange all the insects in perpendicular rows. Put the names of each section, tribe, family, and genus at the head of their respective divisions, and the names of the species below each insect or series of insects. The opposite plan, in which the circles represent the insects themselves, will make this clear.

Three or four specimens of each species are generally sufficient, except where variations in colouring are to be exhibited. Wherever differences exist in the form or markings of the sexes, both should appear; and one specimen of each species should be pinned so as to exhibit the under side.

Finally, each drawer or box should have a neat label outside giving the name or names of the divisions of insects that are represented within. This will enable you to find anything you may require without the necessity of opening drawer after drawer or box after box.

PART III

BRITISH BUTTERFLIES

We have now treated in detail of the changes through which butterflies and moths have to pass, and have studied the methods by which we may obtain and preserve the insects in their different stages. I shall now give such a brief description of individual species as will enable the reader to recognise them readily. We will begin with the butterflies.

CHAPTER XII

THE SWALLOW-TAIL AND THE 'WHITES'

Family – PapilionidæThe Swallow-tail (Papilio Machaon)Our first family (Papilionidæ) contains only one British species – the beautiful Swallow-tail (Papilio Machaon), distinguished at once from all other British butterflies by its superior size and the 'tails' projecting from the hind margin of the hind wings.

This beautiful insect is figured on Plate I, where its bold black markings on a yellow ground are so conspicuous as to render a written description superfluous. Attention may be called, however, to the yellow scales that dot the dark bands and blotches, making them look as if they had been powdered; also to the blue clouds that relieve the black bands of the hind wings, and the round reddish orange spot at the anal angle of each of the same wings.

It appears that this butterfly was once widely distributed throughout England, having been recorded as common in various counties, and has also been taken in Scotland and Ireland; but it is now almost exclusively confined to the fens of Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, and Norfolk. Occasionally we hear of the capture of single specimens quite outside these localities, sometimes even in most unlikely spots, where its food plant does not abound. But we know that Machaon is a general favourite with entomologists, and that it is sent in the pupal state, by post, to all parts of the kingdom; so that the occasional capture of the insect far beyond the borders of its haunts is probably the outcome of an escape from prison, or of the tender-heartedness of some lover of nature who could not bear to see such a beautiful creature deprived of its short but joyous, sunny flight.

You cannot hope to see this splendid butterfly on the wing unless you visit its haunts during its season – May to August; but the pupæ may be purchased for a few pence each from most of the entomological dealers; and if you obtain a few of these and watch them closely, you may be fortunate enough to see the perfect insect emerge from its case, and witness the gradual expansion of its beautiful wings.

The pupa (Plate VIII, fig. 7) itself is a most beautiful object. Its colour is a pale green, and it is fixed to its support by the tail, and further secured by a very strong silk band.

The larva (Plate VIII, fig. 1), too, is exceedingly beautiful. Its ground colour is a lovely green, and twelve velvety black rings mark the divisions between the segments. Between these are also black bars, all spotted with bright orange except the one on the second segment.

A remarkable feature of this larva is the possession of a forked, Y-shaped 'horn,' that is projected from the back, just behind the head, when the creature is alarmed. If it is gently pressed or irritated in any way, this horn is thrust out just as if it were an important weapon of defence. And perhaps it is, for it is the source of a powerful odour of fennel – one of the food plants of the caterpillar – that may possibly prove objectionable to some of its numerous enemies.

The food plants of Machaon are the milk parsley or hog's fennel (Peucedanum palustre), cow-parsnip (Heracleum sphondylium), and the wild angelica (Angelica sylvestris); but in confinement it will also partake of rue and carrot leaves.

The caterpillar of this species may be found in the fens during the greater part of the summer. It turns to a chrysalis in the autumn, and remains in this state throughout the winter, attached to the stems of reeds in the vicinity of its food plants. The perfect insect is first seen in May, and is more or less abundant from this time to the month of August.

Family – PieridæThis family, though known commonly as the 'Whites,' contains four British species that display beautiful tints of bright yellow or orange.

In many respects the Pieridæ resemble the last species. Thus the perfect insects have six fully developed legs; the caterpillars are devoid of bristles or spines; and the chrysalides are attached by means of silky webs at the 'tails,' and strong cords of the same material round the middle.

All the larvæ are also cylindrical or wormlike in shape; and their skins are either quite smooth, or are covered with very short and fine hairs, that sometimes impart a soft, velvety appearance.

The members of this family are remarkable for their partiality for certain of our cultivated plants and trees; and are, in some cases, so abundant and so voracious, that they are exceedingly destructive to certain crops.

The Black-veined White (Aporia Cratægi)This butterfly may now be regarded as one of our rarities. At one time it was rather abundant in certain localities in England, among which may be mentioned the neighbourhoods of Cardiff and Stroud, also parts of Kent, Sussex, Hampshire, Huntingdonshire, and the Isle of Thanet; but it is to be feared that this species is nearly or quite extinct in this country. It is well, however, not to give up the search for it, and if you happen to be in one of its favoured localities of former days, you might net all the doubtful 'Whites' of large size that arouse your suspicions, liberating them again if, on inspection, they do not answer to the description of the species 'wanted.' This course becomes absolutely necessary, since the Black-veined White is hardly to be distinguished from the Common Large White while on the wing.

If you examine a number of British butterflies you will observe that in nearly all species the wings are bordered by a fringe of hair, more or less distinct. But the case is different with Cratægi. Here they are bordered by a black nervure, without any trace of fringe, thus giving an amount of rigidity to the edges (see Plate I, fig. 2).

The wing rays, or nervures, are very distinct – a feature that gave rise to the popular name of the butterfly. In the male they are quite or nearly black, but those of the fore wings of the female are decidedly brown in colour. At the terminations of the wing rays there are triangular patches of dark scales, the bases of which unite on the outer margins of the wings.

Another peculiar feature of this insect is the scanty distribution of scales on the wings. This is particularly so in the case of the female, whose wings are semi-transparent in consequence.

The butterfly is on the wing during June and July, at which time its eggs are laid on the hawthorn (Cratægus Oxyacantha) or on fruit trees – apple, pear and plum.

A vigorous search of these trees in the proper localities may reveal to you a nest of the gregarious larvæ, all resting under the cover of a common web of silk. These remain thus under their silken tent throughout the hottest hours of the day, and venture out to feed only during the early morning and in the evening.

When the leaves begin to fall in the autumn, they construct a more substantial web to protect themselves from the dangers of the winter, and in this they hybernate till the buds burst in the following spring. They now venture out, at first during the mildest days only, and feed voraciously on the young leaves, returning to their homes to rest. Soon, however, they gradually lose their social tendencies, till at last, when about half or three-quarters fed, they become quite solitary in their habits.

In May they are fully grown, and change to the chrysalis state on the twigs of their food trees.

The larva is black above, with two reddish stripes. The sides and under surface are grey, the former being relieved by black spiracles.

The pupa (page 45) is greenish or yellowish white, striped with bright yellow, and spotted with black.

It is probable that the reader will never meet with this insect in any of its stages. But, though it may have left us, it is still very abundant on the Continent, where it does great damage to fruit trees; and the foreign pupæ may be purchased of English dealers.

The Large White (Pieris Brassicæ)We pass now from one of the rarest to one of the most abundant of British butterflies. Everybody has seen the 'Large White,' though we doubt whether everybody knows that this insect is not of the same species as the two other very common 'Whites.' The three – Large, Small, and Green-veined – are so much alike in general colour and markings, and so similar in their habits and in the selection of their food plants, that the non-entomological, not knowing that insects do not grow in their perfect state, may perhaps regard the larger and the smaller as older and younger members of the same species. But no – they are three distinct species, exhibiting to a careful observer many important marks by which each may be known from the other two.

On Plate I (fig. 3) will be seen a picture of the female Brassicæ, in which the following markings are depicted: On each fore wing – a blotch at the tip, a round spot near the centre, another round one nearer the inner margin, and a tapering spot on the inner margin with its point toward the base of the wing. On the hind wings there is only one spot, situated near the middle of the costal margin.

The male may be readily distinguished by the absence of the black markings on the fore wings, with the exception of those at the tips. He is also a trifle smaller than his mate.

This butterfly is double-brooded. The first brood appears in April and May, the second in July and August; and the former – the spring brood – which emerges from the chrysalides that have hybernated during the winter, have grey rather than black tips to the front wings.

The ova of Brassicæ may be found on the leaves of cabbages in every kitchen garden, also on the nasturtium, during May and July. They are pretty objects (see fig. 10), something like little bottles or sculptured vases standing on end, and are arranged either singly or in little groups.

As soon as the young larvæ are out – from ten to fifteen days after the eggs are deposited – having devoured their shells, they start feeding on the selfsame spot, and afterwards wander about, dealing out destruction as they go, till little remains of their food plant save the mere stumps and skeletons of the leaves.

The ground colour of the caterpillar is bluish green. It has a narrow yellow stripe down the middle of the back, and two similar but wider stripes along the sides; and the surface of the body is rendered somewhat rough by a number of small black warty projections, from each of which arises a short hair.

When fully grown, it creeps to some neighbouring wall or fence, up which it climbs till it reaches a sheltering ledge. Here it constructs its web and silken cord as already described (page 36), and then changes to a bluish-white chrysalis, dotted with black. The butterflies of the summer brood emerge shortly after, but the chrysalides of the next brood hybernate till the following spring.

It is remarkable that we are so plagued with 'Whites' seeing that they have so many enemies. Many of the insect-feeding birds commit fearful havoc among their larvæ, and often chase the perfect insects on the wing, but perhaps their greatest enemy is the ichneumon fly.

Look under the ledges of a wall of any kitchen garden, and you will see little clusters of oval bodies of a bright yellow colour. Most gardeners know that these are in some way or other connected with the caterpillars that do so much damage to their vegetables. They are often considered to be eggs laid by the larvæ, and are consequently killed out of pure revenge, or with a desire to save the crops from the future marauders.

No greater mistake could be made. These yellow bodies are the silken cocoons of the caterpillar's own foes. They contain the pupæ of the little flies whose larvæ have lived within the body of an unfortunate grub, and, having flourished to perfection at the expense of their host, left its almost empty and nearly lifeless carcase to die and drop to the ground just at the time when it ought to be working out its final changes. Often you may see the dying grub beside the cluster of cocoons just constructed by its deadly enemies. Should you wish to test the extent of the destructive work of these busy flies, go into your garden and collect a number of larvæ, and endeavour to rear them under cover. The probability is that only a small proportion will ever reach the final state, the others having been fatally 'stung' before you took them.

The Small White (P. Rapæ)This butterfly closely resembles the last species except in point of size. The male, represented on Plate I (fig. 4), has a dark grey blotch at the tip of each fore wing, a round spot of the same colour beyond the centre of that wing, and another on the costal margin of the hind wing. The female may be distinguished by an additional spot near the anal angle of the fore wing.

Although this and the two other common butterflies (Brassicæ and Napi) that frequent our kitchen gardens are usually spoken of as 'Whites,' a glance at a few specimens will show that they are not really white at all, but exhibit delicate shades of cream and yellow, inclining sometimes to buff. The under surfaces are particularly noticeable in this respect, for here the hind wings and the tips of the fore wings display a very rich yellow.

The species we are now considering is also very variable both in its ground colour and the markings of the wings. The former is in some cases a really brilliant yellow; and the latter are in some cases entirely wanting.

Rapæ is double-brooded, the first brood appearing in April and May, and the other in July and August.

During these months the eggs may be seen in plenty on its numerous food plants, which include the cabbages and horse-radish of our gardens, also water-cress (Nasturtium officinale), rape (Brassica Napus), wild mustard (B. Sinapis), wild mignonette (Reseda lutea), and nasturtium (Tropæolum majus).

The eggs are conical in form – something like a sugar loaf, with ridges running from apex to base, and very delicate lines from ridge to ridge transversely.