полная версия

полная версияA History of Chinese Literature

“There is in the universe an Aura which permeates all things and makes them what they are. Below, it shapes forth land and water; above, the sun and the stars. In man it is called spirit; and there is nowhere where it is not.

“In times of national tranquillity this spirit lies perdu in the harmony which prevails; only at some great crisis is it manifested widely abroad.”

[Here follow ten historical instances of devotion and heroism.]

“Such is this grand and glorious spirit which endureth for all generations, and which, linked with the sun and the moon, knows neither beginning nor end. The foundation of all that is great and good in heaven and earth, it is itself born from the everlasting obligations which are due by man to man.

“Alas! the fates were against me. I was without resource. Bound with fetters, hurried away towards the north, death would have been sweet indeed; but that boon was refused.

“My dungeon is lighted by the will-o’-the-wisp alone; no breath of spring cheers the murky solitude in which I dwell. The ox and the barb herd together in one stall, the rooster and the phœnix feed together from one dish. Exposed to mist and dew, I had many times thought to die; and yet, through the seasons of two revolving years, disease hovered round me in vain. The dank, unhealthy soil to me became paradise itself. For there was that within me which misfortune could not steal away. And so I remained firm, gazing at the white clouds floating over my head, and bearing in my heart a sorrow boundless as the sky.

“The sun of those dead heroes has long since set, but their record is before me still. And, while the wind whistles under the eaves, I open my books and read; and lo! in their presence my heart glows with a borrowed fire.”

“I myself,” adds the famous commentator, Lin Hsi-chung, of the seventeenth century, “in consequence of the rebellion in Fuhkien, lay in prison for two years, while deadly disease raged around. Daily I recited this poem several times over, and happily escaped; from which it is clear that the supremest efforts in literature move even the gods, and that it is not the verses of Tu Fu alone which can prevail against malarial fever.”

At the final examination for his degree in 1256, Wên T’ien-hsiang had been placed seventh on the list. However, the then Emperor, on looking over the papers of the candidates before the result was announced, was immensely struck by his work, and sent for the grand examiner to reconsider the order of merit. “This essay,” said his Majesty, “shows us the moral code of the ancients as in a mirror; it betokens a loyalty enduring as iron and stone.” The grand examiner readily admitted the justice of the Emperor’s criticism, and when the list was published, the name of Wên T’ien-hsiang stood first. The fame of that examiner, Wang Ying-lin (1223-1296), is likely to last for a long time to come. Not because of his association with one of China’s greatest patriots, nor because of his voluminous contributions to classical literature, including an extensive encyclopædia, a rare copy of which is to be seen in the University of Leyden, but because of a small primer for schoolboys, which, by almost universal consent, is attributed to his pen. For six hundred years this primer has been, and is still at this moment, the first book put into the hand of every child throughout the empire. It is an epitome of all knowledge, dealing with philosophy, classical literature, history, biography, and common objects. It has been called a sleeve edition of the Mirror of History. Written in lines of three characters to each, and being in doggerel rhyme, it is easily committed to memory, and is known by heart by every Chinaman who has learnt to read. This Three Character Classic, as it is called, has been imitated by Christian missionaries, Protestant and Catholic; and even the T’ai-p’ing rebels, alive to its far-reaching influence, published an imitation of their own. Here are a few specimen lines, rhymed to match the original: —

“Men, one and all, in infancyAre virtuous at heart;Their moral tendencies the same,Their practice wide apart.Without instruction’s kindly aidMan’s nature grows less fair;In teaching, thoroughness should beA never-ceasing care.”It may be added that the meaning of the Three Character Classic is not explained to the child at the time. All that the latter has to do is to learn the sounds and formation of the 560 different characters of which the book is composed.

LIU YIN

A clever boy, who attracted much attention by the filial piety which he displayed towards his stepfather, was Liu Yin (1241-1293). He obtained office, but resigned in order to tend his sick mother; and when again appointed, his health broke down and he went into seclusion. The following extract is from his pen: —

“When God made man, He gave him powers to cope with the exigencies of his environment, and resources within himself, so that he need not be dependent upon external circumstances.

“Thus, in districts where poisons abound, antidotes abound also; and in others, where malaria prevails, we find such correctives as ginger, nutmegs, and dogwood. Again, fish, terrapins, and clams are the most wholesome articles of diet in excessively damp climates, though themselves denizens of the water; and musk and deer-horns are excellent prophylactics in earthy climates, where in fact they are produced. For if these things were unable to prevail against their surroundings, they could not possibly thrive where they do, while the fact that they do so thrive is proof positive that they were ordained as specifics against those surroundings.

“Chu Hsi said, ‘When God is about to send down calamities upon us, He first raises up the hero whose genius shall finally prevail against those calamities.’ From this point of view there can be no living man without his appointed use, nor any state of society which man should be unable to put right.”

The theory that every man plays his allotted part in the cosmos is a favourite one with the Chinese; and the process by which the tares are separated from the wheat, exemplifying the use of adversity, has been curiously stated by a Buddhist priest of this date: —

“If one is a man, the mills of heaven and earth grind him to perfection; if not, to destruction.”

A considerable amount of poetry was produced under the Mongol sway, though not so much proportionately, nor of such a high order, as under the great native dynasties. The Emperor Ch’ien Lung published in 1787 a collection of specimens of the poetry of this Yüan dynasty. They fill eight large volumes, but are not much read.

LIU CHI

One of the best known poets of this period is Liu Chi (A.D. 1311-1375), who was also deeply read in the Classics and also a student of astrology. He lived into the Ming dynasty, which he helped to establish, and was for some years the trusted adviser of its first ruler. He lost favour, however, and was poisoned by a rival, it is said, with the Emperor’s connivance. The following lines, referring to an early visit to a mountain monastery, reveal a certain sympathy with Buddhism: —

“I mounted when the cock had just begun,And reached the convent ere the bells were done;A gentle zephyr whispered o’er the lawn;Behind the wood the moon gave way to dawn.And in this pure sweet solitude I lay,Stretching my limbs out to await the day,No sound along the willow pathway dimSave the soft echo of the bonzes’ hymn.”Here too is an oft-quoted stanza, to be found in any poetry primer: —

“A centenarian ’mongst menIs rare; and if one comes, what then?The mightiest heroes of the pastUpon the hillside sleep at last.”The prose writings of Liu Chi are much admired for their pure style, which has been said to “smell of antiquity.” One piece tells how a certain noble who had lost all by the fall of the Ch’in dynasty, B.C. 206, and was forced to grow melons for a living, had recourse to divination, and went to consult a famous augur on his prospects.

“Alas!” cried the augur, “what is there that Heaven can bestow save that which virtue can obtain? Where is the efficacy of spiritual beings beyond that with which man has endowed them? The divining plant is but a dead stalk; the tortoise-shell a dry bone. They are but matter like ourselves. And man, the divinest of all things, why does he not seek wisdom from within, rather than from these grosser stuffs?

“Besides, sir, why not reflect upon the past – that past which gave birth to this present? Your cracked roof and crumbling walls of to-day are but the complement of yesterday’s lofty towers and spacious halls. The straggling bramble is but the complement of the shapely garden tree. The grasshopper and the cicada are but the complement of organs and flutes; the will-o’-the-wisp and firefly, of gilded lamps and painted candles. Your endive and watercresses are but the complement of the elephant-sinews and camel’s hump of days bygone; the maple-leaf and the rush, of your once rich robes and fine attire. Do not repine that those who had not such luxuries then enjoy them now. Do not be dissatisfied that you, who enjoyed them then, have them now no more. In the space of a day and night the flower blooms and dies. Between spring and autumn things perish and are renewed. Beneath the roaring cascade a deep pool is found; dark valleys lie at the foot of high hills. These things you know; what more can divination teach you?”

Another piece is entitled “Outsides,” and is a light satire on the corruption of his day: —

“At Hangchow there lived a costermonger who understood how to keep oranges a whole year without letting them spoil. His fruit was always fresh-looking, firm as jade, and of a beautiful golden hue; but inside – dry as an old cocoon.

“One day I asked him, saying, ‘Are your oranges for altar or sacrificial purposes, or for show at banquets? Or do you make this outside display merely to cheat the foolish? as cheat them you most outrageously do.’ ‘Sir,’ replied the orangeman, ‘I have carried on this trade now for many years. It is my source of livelihood. I sell; the world buys. And I have yet to learn that you are the only honest man about, and that I am the only cheat. Perhaps it never struck you in this light. The bâton-bearers of to-day, seated on their tiger skins, pose as the martial guardians of the State; but what are they compared with the captains of old? The broad-brimmed, long-robed Ministers of to-day pose as pillars of the constitution; but have they the wisdom of our ancient counsellors? Evil-doers arise, and none can subdue them. The people are in misery, and none can relieve them. Clerks are corrupt, and none can restrain them. Laws decay, and none can renew them. Our officials eat the bread of the State and know no shame. They sit in lofty halls, ride fine steeds, drink themselves drunk with wine, and batten on the richest fare. Which of them but puts on an awe-inspiring look, a dignified mien? – all gold and gems without, but dry cocoons within. You pay, sir, no heed to these things, while you are very particular about my oranges.’

“I had no answer to make. Was he really out of conceit with the age, or only quizzing me in defence of his fruit?”

CHAPTER II

THE DRAMA

THE DRAMA

If the Mongol dynasty added little of permanent value to the already vast masses of poetry, of general literature, and of classical exegesis, it will ever be remembered in connection with two important departures in the literary history of the nation. Within the century covered by Mongol rule the Drama and the Novel may be said to have come into existence. Going back to pre-Confucian or legendary days, we find that from time immemorial the Chinese have danced set dances in time to music on solemn or festive occasions of sacrifice or ceremony. Thus we read in the Odes: —

“Lightly, sprightly,To the dance I go,The sun shining brightlyIn the court below.”The movements of the dancers were methodical, slow, and dignified. Long feathers and flutes were held in the hand and were waved to and fro as the performers moved right or left. Words to be sung were added, and then gradually the music and singing prevailed over the dance, gesture being substituted. The result was rather an operatic than a dramatic performance, and the words sung were more of the nature of songs than of musical plays. In the Tso Chuan, under B.C. 545, we read of an amateur attempt of the kind, organised by stable-boys, which frightened their horses and caused a stampede. Confucius, too, mentions the arrogance of a noble who employed in his ancestral temple the number of singers reserved for the Son of Heaven alone. It is hardly necessary to allude to the exorcism of evil spirits, carried out three times a year by officials dressed up in bearskins and armed with spear and shield, who made a house to house visitation surrounded by a shouting and excited populace. It is only mentioned here because some writers have associated this practice with the origin of the drama in China. All we really know is that in very early ages music and song and dance formed an ordinary accompaniment to religious and other ceremonies, and that this continued for many centuries.

Towards the middle of the eighth century, A.D., the Emperor Ming Huang of the T’ang dynasty, being exceedingly fond of music, established a College, known as the Pear-Garden, for training some three hundred young people of both sexes. There is a legend that this College was the outcome of a visit paid by his Majesty to the moon, where he was much impressed by a troup of skilled performers attached to the Palace of Jade which he found there. It was apparently an institution to provide instrumentalists, vocalists, and possibly dancers, for Court entertainments, although some have held that the “youths of the Pear-Garden” were really actors, and the term is still applied to the dramatic fraternity. Nothing, however, which can be truly identified with the actor’s art seems to have been known until the thirteenth century, when suddenly the Drama, as seen in the modern Chinese stage-play, sprang into being. In the present limited state of our knowledge on the subject, it is impossible to say how or why this came about. We cannot trace step by step the development of the drama in China from a purely choral performance, as in Greece. We are simply confronted with the accomplished fact.

At the same time we hear of dramatic performances among the Tartars at a somewhat earlier date. In 1031 K’ung Tao-fu, a descendant of Confucius in the forty-fifth degree, was sent as envoy to the Kitans, and was received at a banquet with much honour. But at a theatrical entertainment which followed, a piece was played in which his sacred ancestor, Confucius, was introduced as the low-comedy man; and this so disgusted him that he got up and withdrew, the Kitans being forced to apologise. Altogether, it would seem that the drama is not indigenous to China, but may well have been introduced from Tartar sources. However this may be, it is certain that the drama as known under the Mongols is to all intents and purposes the drama of to-day, and a few general remarks may not be out of place.

Plays are acted in the large cities of China at public theatres all the year round, except during one month at the New Year, and during the period of mourning for a deceased Emperor. There is no charge for admission, but all visitors must take some refreshment. The various Trade-Guilds have raised stages upon their premises, and give periodical performances free to all who will stand in an open-air courtyard to watch them. Mandarins and wealthy persons often engage actors to perform in their private houses, generally while a dinner-party is going on. In the country, performances are provided by public subscription, and take place at temples or on temporary stages put up in the roadway. These stages are always essentially the same. There is no curtain, there are no wings, and no flies. At the back of the stage are two doors, one for entrance and one for exit. The actors who are to perform the first piece come in by the entrance door all together. When the piece is over, and as they are filing out through the exit door, those who are cast for the second piece pass in through the other door. There is no interval, and the musicians, who sit on the stage, make no pause; hence many persons have stated that Chinese plays are ridiculously long, the fact being that half-an-hour to an hour would be about an average length for the plays usually performed, though much longer specimens, such as would last from three to five hours, are to be found in books. Eight or ten plays are often performed at an ordinary dinner-party, a list of perhaps forty being handed round for the chief guests to choose from.

The actors undergo a very severe physical training, usually between the ages of nine and fourteen. They have to learn all kinds of acrobatic feats, these being introduced freely into “military” plays. They also have to practise walking on feet bound up in imitation of women’s feet, no woman having been allowed on the stage since the days of the Emperor Ch’ien Lung (A.D. 1736-1796), whose mother had been an actress. They have further to walk about in the open air for an hour or so every day, the head thrown back and the mouth wide open in order to strengthen the voice; and finally, their diet is carefully regulated according to a fixed system of training. Fifty-six actors make up a full company, each of whom must know perfectly from 100 to 200 plays, there being no prompter. These do not include the four- or five-act plays as found in books, but either acting editions of these, cut down to suit the requirements of the stage, or short farces specially written. The actors are ranged under five classes according to their capabilities, and consequently every one knows what part he is expected to take in any given play. Far from being an important personage, as in ancient Greece, the actor is under a social ban; and for three generations his descendants may not compete at the public examinations. Yet he must possess considerable ability in a certain line; for inasmuch as there are no properties and no realism, he is wholly dependent for success upon his own powers of idealisation. There he is indeed supreme. He will gallop across the stage on horseback, dismount, and pass his horse on to a groom. He will wander down a street, and stop at an open shop-window to flirt with a pretty girl. He will hide in a forest, or fight from behind a battlemented wall. He conjures up by histrionic skill the whole paraphernalia of a scene which in Western countries is grossly laid out by supers before the curtain goes up. The general absence of properties is made up to some extent by the dresses of the actors, which are of the most gorgeous character, robes for Emperors and grandees running into figures which would stagger even a West-end manager.

It is obvious that the actor must be a good contortionist, and excel in gesture. He must have a good voice, his part consisting of song and “spoken” in about equal proportions. To show how utterly the Chinese disregard realism, it need only be stated that dead men get up and walk off the stage; sometimes they will even act the part of bearers and make movements as though carrying themselves away. Or a servant will step across to a leading performer and hand him a cup of tea to clear his voice.

The merit of the plays performed is not on a level with the skill of the performer. A Chinese audience does not go to hear the play, but to see the actor. In 1678, at a certain market-town, there was a play performed which represented the execution of the patriot, General Yo Fei (A.D. 1141), brought about by the treachery of a rival, Ch’in Kuei, who forged an order for that purpose. The actor who played Ch’in Kuei (a term since used contemptuously for a spittoon) produced a profound sensation; so much so, that one of the spectators, losing all self-control, leapt upon the stage and stabbed the unfortunate man to death.

Most Chinese plays are simple in construction and weak in plot. They are divided into “military” and “civil,” which terms have often been wrongly taken in the senses of tragedy and comedy, tragedy proper being quite unknown in China. The former usually deal with historical episodes and heroic or filial acts by historical characters; and Emperors and Generals and small armies rush wildly about the stage, sometimes engaged in single combat, sometimes in turning head over heels. Battles are fought and rivals or traitors executed before the very eyes of the audience. The “civil” plays are concerned with the entanglements of every-day life, and are usually of a farcical character. As they stand in classical collections or in acting editions, Chinese plays are as unobjectionable as Chinese poetry and general literature. On the stage, however, actors are allowed great license in gagging, and the direction which their gag takes is chiefly the reason which keeps respectable women away from the public play-house.

It must therefore always be remembered that there is the play as it can be read in the library, and again as it appears in the acting edition to be learnt, and finally as it is interpreted by the actor. These three are often very different one from the other.

The following abstract will give a fair idea of the pieces to be found on the play-bill of any Chinese theatre: —

The Three Suspicions.

At the close of the Ming dynasty, a certain well-known General was occupied day and night in camp with preparations for resisting the advance of the rebel army which ultimately captured Peking. While thus temporarily absent from home, the tutor engaged for his son fell ill with severe shivering fits, and the boy, anxious to do something to relieve the sufferer, went to his mother’s room and borrowed a thick quilt. Late that night, the General unexpectedly returned home, and heard from a slave-girl in attendance of the tutor’s illness and of the loan of the quilt. Thereupon, he proceeded straight to the sick-room, to see how the tutor was getting on, but found him fast asleep. As he was about to retire, he espied on the ground a pair of women’s slippers, which had been accidentally brought in with the quilt, and at once recognised to whom they belonged. Hastily quitting the still sleeping tutor, and arming himself with a sharp scimitar, he burst into his wife’s apartment. He seized the terrified woman by the hair, and told her that she must die; producing, in reply to her protestations, the fatal pair of slippers. He yielded, however, to the entreaties of the assembled slave-girls, and deferred his vengeance until he had put the following test. He sent a slave-girl to the tutor’s room, himself following close behind with his naked weapon ready for use, bearing a message from her mistress to say she was awaiting him in her own room; in response to which invitation the voice of the tutor was heard from within, saying, “What! at this hour of the night? Go away, you bad girl, or I will tell the master when he comes back!” Still unconvinced, the jealous General bade his trembling wife go herself and summon her paramour; resolving that if the latter but put foot over the threshold, his life should pay the penalty. But there was no occasion for murderous violence. The tutor again answered from within the bolted door, “Madam, I may not be a saint, but I would at least seek to emulate the virtuous Chao Wên-hua (the Joseph of China). Go, and leave me in peace.” The General now changes his tone; and the injured wife, she too changes hers. She attempts to commit suicide, and is only dissuaded by an abject apology on the part of her husband; in the middle of which, as the latter is on his knees, a slave-girl creates roars of laughter by bringing her master, in mistake for wine, a brimming goblet of vinegar, the Chinese emblem of connubial jealousy.

The following is a translation of the acting edition of a short play, as commonly performed, illustrating, but not to exaggeration, the slender and insufficient literary art which satisfies the Chinese public, the verses of the original being quite as much doggerel as those of the English version: —

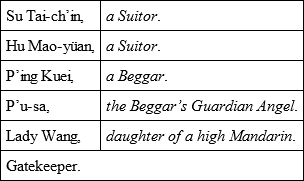

THE FLOWERY BALLDramatis Personæ:

Even the longer and more elaborate plays are proportionately wanting in all that makes the drama piquant to a European, and are very seldom, if ever, produced as they stand in print. Many collections of these have been published, not to mention the acting editions of each play, which can be bought at any bookstall for something like three a penny. One of the best of such collections is the Yüan ch’ü hsüan tsa chi, or Miscellaneous Selection of Mongol Plays, bound up in eight thick volumes. It contains one hundred plays in all, with an illustration to each, according to the edition of 1615. A large proportion of these cannot be assigned to any author, and are therefore marked “anonymous.” Even when the authors’ names are given, they represent men altogether unknown in what the Chinese call literature, from which the drama is rigorously excluded.