полная версия

полная версияThe Notting Hill Mystery

5. —Extracts from Dr. Marsden's Diary21

MAY 23rd. – Madame R**, nausea, vomiting, tendency to diarrhoea, profuse perspiration, and general debility. Pulse low, 100. Spirits depressed. Burning pain in stomach – abdomen tender on pressure. Tongue discoloured.

26th. – Madame R** slightly better – less nausea and pain.

30th. – Madame R**. Improvement continues.

JUNE 2nd. – Madame R** improving.

6th. – Ditto.

9th. – Recurrence of symptoms on Saturday evening.22 Increased nausea, vomited matter yellow with bile. Pulse low, 105. Throat sore, and slight constriction. Tongue foul.

13th. – Symptoms slightly ameliorated. Treatment continued.

16th. – Ditto. Tongue slightly clearer. Pulse 100.

20th. – Improvement continued. Pulse slightly firmer.

23rd. – Ditto.

24th. – Special visit. Return of symptoms last night. Great increase of nausea and vomiting – very yellow with bile. Throat sore and tongue foul. Abdomen very tender on pressure. Slight diarrhoea. Tingling sensation in limbs.

27th. – Slight improvement.

30th. – Continued, but slight. Pulse firmer.

JULY 3rd. – Improvement continued, especially in throat. Perspiration still distressing. Less tingling in limbs.

6th. – Improvement continued. Pulse somewhat firmer, 110.

(10th to 20th. – Absent in Gloucestershire.)

20th. – A slight rally. Baron says attack shortly after last visit, but recovery for time more rapid.

24th. – Improvement continues, but less rapid. Pulse 110.

27th. – Recurrence yesterday. Vomiting, purging amounting to diarrhoea. Soreness and aphthous state of mouth and throat. Perspiration. Pain in abdomen. Complains of taste in mouth like lead. Pulse low, 115. Qy. antimony? Speak, Baron.

31st. – Analysis – satisfactory. Symptoms slightly abated.

AUGUST 3rd. – Improvement continued. Pulse 112, firmer.

7th. – Same.

10th. – Return of vomiting and purging. General aggravation of symptoms. Much prostrated.

24th, 28th, 31st. – Slight improvement.

SEPTEMBER 4th. – Improvement continued, but slight.

7th. – Return of severe symptoms. Vomiting, extremely yellow, much bile. Diarrhoea. Pulse low and fluttering, 120. Violent perspiration. Slight wandering. Extreme soreness and constriction of throat. Slight convulsive twitchings in limbs. Great exhaustion and prostration.

10th, 14th, 18th. – Very slight abatement of symptoms.

21st. – Violence of symptoms increased. Pulse 125. Great prostration.

25th, 28th. – Very slight amelioration. Pulse 125. Wandering.

OCTOBER 1st, 4th, 8th. – Symptoms slightly less severe.

11th. – Aggravation of all symptoms. Pulse 132, low and fluttering. Face flushed and pale. Much convulsive twitching in limbs. Power of speech quite gone. Entire prostration. Can hardly live through night.

12th, 13th, 14th. – Special visits. No perceptible change.

15th. – Pulse a shade firmer, 136.

N.B. – From this date recovery slow but steady.

6. —Memorandum by Mr. Henderson.

From the very vague nature of the foregoing evidence, so far as dates are concerned, it was, as you will at once perceive, no very easy task to determine the precise day of Madame R**'s first attack. To the view of the case, however, which I was even then inclined to adopt this was a matter of the last importance, and I determined to spare no effort to elucidate it if possible from the very loose data furnished by the depositions. In this I have, I think, been successful; but, as the process has been somewhat complicated, I must ask you to follow me through it step by step.

The difficulty of tracing the truth seemed at first sight not a little augmented by the fact that no one had been in the house but Mrs. Brown herself, whose memory, even had it afforded any clue, could not have been relied on. On further consideration, however, I began to fancy myself mistaken in this respect, and finally conceived a hope that this very fact might, if properly handled, prove an assistance instead of an obstacle to my investigation. The following was the course of reasoning I pursued.

There are only two points on which Mrs. Brown appears to be certain; her son's presence in England, and her being herself alone in the house on the actual day in question. The only chances of success therefore seemed to be: – First, in ascertaining precisely the limit of time within which such a combination was possible; and, second, in determining by a process of elimination the actual day or days on which such a combination could fall.

The result has been far more complete than at the outset of the investigation I could venture to hope.

1st. For the period of time to which our researches should be directed.

This was obviously limited by the residence of Richard Brown in England, and my first efforts were therefore directed towards determining the exact dates of his arrival and departure.

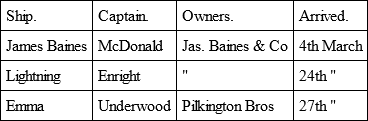

1. On inquiry at Liverpool, I found that the only vessels which had arrived from Melbourne during the month of March, 1856, were as follows:

Of these the James Baines left Melbourne on the 28th November, and the Lightning on the 28th December. The exact date of sailing of the Emma I have not been able to ascertain, but it is immaterial to the case.

The fragment of newspaper preserved by Mrs. Brown has no date, nor could I at first find any clue by which it might be determined. The last paragraph, however, commences as follows:

SEASONABLE WEATHER! – The thermometer has, for the last four days, never been lower than eighty degrees in the shade. We wonder what our friends in England would say to singing their Ch… rols in such a…

The remainder is torn off, but the missing syllables are clearly Christmas Carols, and this shows clearly that the paper must have been published after the departure of the James Baines on the 28th November. Richard Brown must therefore have come home either in the Lightning or the Emma, the earliest of which reached Liverpool on the evening of the 24th March. The 25th of March therefore is the earliest date from which our examination need commence.

2. From Mrs. Troubridge, mother of the young woman to whom Richard Brown was married during his stay in England, I learned that the young couple sailed for Sydney in the Maria Somes. Mrs. Brown was unable to give me the date of this vessel's departure, but a search through the file of the Times for April, 1856, shows that she left Gravesend on the 23rd of that month. The period to be analysed is therefore confined to the interval between the 25th March and the 25th April, 1856.

3. During this period, as we learn from Mrs. Brown's statement, Richard Brown was at home every day except Saturdays and Sundays. These were respectively, 29th and 30th of March, and 5th, 6th, 12th, 13th, 19th, and 20th of April.

4. Dr. Marsden, in his evidence, states most distinctly that he did not see Madame R** until at least "one clear day" had elapsed after her attack. Dr. Marsden's visits take place on the Monday and Friday of each week. Madame R**'s seizure therefore did not occur on a Sunday. This reduces the days on which it may have happened to the 29th March and 5th, 12th, and 19th April.

5. From Mrs. Troubridge's evidence we learn that Mrs. Brown and the whole party slept at Gravesend on the Saturday night previous to the sailing of the Maria Somes. Mrs. Brown was therefore absent from town on the 19th April. The issue is thus narrowed to the 29th March and the 5th and 12th April.

6. From Mrs. Brown's statement we learn that on the Saturday and Sunday preceding the wedding her son's friend Aldridge slept at the house. The wedding took place on the 14th April. On the 12th April, therefore, Mrs. Brown was not alone. The only days, therefore, on which the occurrence, as described, could have taken place are the 29th March and 5th April.

At this point I feared for some time that my clue was at an end. This would, however, have been most unsatisfactory, as the possible error of a week in point of date would have seriously detracted from the trustworthiness of the entire case. The only possible chance of determining the point seemed to lie in ascertaining the precise date of the servant's dismissal, and it at length occurred to me that this might be accomplished by means of the police records of the court before which she was carried. From them I found —

7. That the offence for which she was discharged was committed on Sunday, the 30th of April. On the 29th, therefore, she was still in Mrs. Brown's house. The only day, therefore, on which Madame R**'s first seizure could have taken place as stated during Richard Brown's stay in England, and on a night when Mrs. Brown was alone in the house, was the 5th of April.

The importance of this date, thus fixed, you will, I think, at once perceive.

SECTION VI

1. —Memorandum by Mr. Henderson.

We have now arrived at a point in this extraordinary case at which I must again direct your attention to the will of the late Mr. Boleton. By this will 25,000l. was, as we have seen, bequeathed to Miss Boleton (afterwards Mrs. Anderton), with a life interest, after her death, to her husband. At his decease, and failing children by his marriage with Miss Boleton, the money passed to the second sister, whom, as I have before said, we may, I think, be justified in identifying with the late Madame R**. It seems, at all events, clear, both from the circumstances attending the marriage of the Baron, and from the observation made by him at Bognor to Dr. Marsden relative to the pecuniary loss he would have sustained by the death of his wife, that the Baron himself believed and was prepared to maintain this relationship, and that the various policies of assurance effected on the life of Madame R** – to the gross amount of 25,000l., the exact sum in question, – were intended to cover any risk of her death before that of her sister. This is all that we need at present require. What import should be attached to the degree of mystery with which the whole affair both of the marriage and of the assurance seems to have been so carefully surrounded will, of course, be matter for consideration when reviewing the whole circumstances of the case. It is enough for our present purpose that the Baron clearly looked upon his wife as the sister of Mrs. Anderton, and calculated upon participation, through her, in the legacy of Mr. Boleton. The lives of Mr. and Mrs. Anderton thus alone intervened between this legacy and the Baron's family, and we have thus established, on his part, a direct interest in their decease.

On the death of Mrs. Anderton, under the circumstances detailed in an earlier portion of the case, the life of her husband only now stood in the way of Baron R**'s succession, and it is important to bear this in mind in considering, as we are now about to do, the various circumstances attendant on the death of that gentleman.

The chain of evidence on which hangs, as I have so often said, the sole hypothesis by which I can account for the mysterious occurrences that form the subject of our inquiry, is not only of a purely circumstantial character, but also of a nature at once so delicate and so complicated that the failure of a single link would render the remainder altogether worthless. Unless the case can be made to stand out clearly, step by step, in all its details, from the commencement to the end, its isolated portions become at once a mere chaos of coincidences, singular indeed in many respects, but not necessarily involving any considerable element of suspicion. It is for this reason that I have, as before stated, endeavoured to lay before you in a distinct and separate form each particular portion of the subject. Hitherto our attention has been entirely occupied with the death of Mrs. Anderton, and with various attendant circumstances, the bearing of which upon that occurrence will be more clearly shown hereafter. We have now to consider the very singular circumstances attending the lapse of the second life – that of Mr. Anderton – intervening, as we have seen, between Mr. Boleton's legacy and Madame R**.

For the purpose of this inquiry, I propose adducing pretty much the same evidence as that given at the inquests held on the bodies of Mrs. and Mr. Anderton. The final result of the former of these inquests was, as you are aware, a verdict of "Died from natural causes," though the case was at first adjourned for a fortnight in order to admit of a more searching examination of the body, during which time Mr. Anderton remained in custody in his own house. In the latter case the jury, after some hesitation, returned a verdict of "Temporary insanity, brought on by extreme distress of mind at the death of his wife, and suspicions respecting it which subsequently proved to have been unfounded." Our present concern, however, being with the conduct of the Baron rather than with that of Mr. Anderton, I have omitted portions not directly bearing upon this part in the matter, and have endeavoured to procure such additions to the evidence of Doctor Dodsworth and others as might serve to further elucidate the subject of our inquiry.

I now therefore lay before you this portion of the case with especial reference to its bearing upon the proceedings of Baron R**.

2. —Doctor Dodsworth's Statement.

I was in attendance on the late Mrs. Anderton during the illness which terminated fatally on the 12th October, 1856. I was first sent for by Mr. Anderton, on the night of the 5th of April23 in that year. I found her suffering apparently from a slight attack of English cholera, but was unable to ascertain any cause to which it might be attributed. There was nothing to lead to any suspicion of poisoning, indeed this seemed to be rendered almost impossible by the length of time that had elapsed since the last time of taking food and that at which the attack commenced. This was at least three or four hours; whereas, had the symptoms arisen from the action of any poisonous substance, they would have shown themselves much earlier. This is only my impression from after consideration. No idea of poison occurred to me at the time, nor should I now entertain any were I called in to a similar case. I prescribed the usual remedies for the complaint under which I supposed Mrs. Anderton to be suffering. They appeared to have their effect, though not so rapidly as I should have expected. The symptoms appeared rather to wear themselves out. I visited her several times, as the debility which ensued seemed greater than, under ordinary circumstances, should have followed on such an attack. About a fortnight later she had a fresh seizure, of a very similar kind. This time, however, the symptoms were aggravated, and accompanied by others of a more alarming character. Of these the most conspicuous were nausea, vomiting, violent perspiration, and increasing tendency to diarrhoea. The patient also complained of great sinking of the heart, and of a terrible lowness of spirits, almost amounting to a conviction that death was at hand. In the course of another fortnight or three weeks there was a fresh recurrence of the symptoms. The tongue, which in the former attacks had been clammy and dry, was now covered thickly with dirty mucus, and there was a greatly increased flow of saliva. The condition of the tongue became greatly aggravated as the disease progressed, the mouth and throat becoming ultimately very sore, with great constriction of the latter. The abdomen was distended, and very tender to the touch, the liver also being very full and tender. Pulse low and rapid, decreasing in fulness as the disease progressed, and reaching finally to 130 or 140; and the depression of spirits and sinking at the heart considerably increased. The patient appeared to be daily losing strength, and at each attack, which seemed to return periodically at intervals of about a fortnight, the same symptoms appeared more severely than before. Mr. Anderton seemed to be in the deepest distress. From the time when the symptoms first became serious, he hardly ever left her side, administering both food and medicine with his own hand. So far as I am aware, Mrs. Anderton took nothing of any kind from any other person throughout the greater portion of her illness. I have heard her say this herself, in his presence, shortly before her death. For the last few weeks she took scarcely any nourishment, and could with difficulty swallow her medicine. The principal cause of this difficulty lay in the extreme nausea which followed any attempt to swallow, but it was greatly increased by the painful and constricted state of the throat, which was extremely rough and raw, and rendered swallowing very painful. As the disease progressed the vomited matter became strongly coloured with bile, and was of a strong yellow colour. The opression on the heart also increased, until at length respiration was almost impeded. The heart and pulses also gradually lost power, and latterly the lower portion of the body was almost paralysed, the limbs being stiff, and the whole frame, from the waist downward, very heavy and cold. The patient also suffered from severe cold perspirations, as well as from heat and irritation of the upper portion of the body, and from entire inability to sleep. A very remarkable feature in the case was, that notwithstanding this general sleeplessness, each fresh attack of the malady was preceded by a sound slumber of some hours duration, from which she appeared to be aroused by the return of the more active symptoms of the disorder. I tried all the usual remedies indicated by such symptoms, but without any permanent effect, and I was a good deal perplexed by the anomalous appearance of the case, and especially by its intermittent character, the symptoms recurring, as I have said, with increased severity, at regular intervals of about a fortnight. I mentioned my difficulty to Mr. Anderton, and asked if he would wish further advice. At his urgent request I consented, though with some hesitation, to meet Baron R**, who holds, as I was given to understand, a regular diploma from several of the foreign Universities, but whose practice has been of a somewhat irregular character. I first consulted with him on the 12th July.24

[Dr. Dodsworth here details at some length how he became convinced of the Baron's great skill and knowledge of chemistry, and was finally persuaded to meet him in consultation.]

After examination of the patient, however, and some conversation as to the nature of the symptoms and of the remedies employed, I had some difficulty in drawing from him (the Baron) any expression of opinion. He appeared, however, to agree entirely in the course hitherto pursued, and after some further conversation we separated. The consultation took place in Mrs. Anderton's dressing-room, and in passing by the wash-hand stand on his way out, the Baron suddenly took up a small bottle which was standing there, and turning sharply upon me, asked "if I had tried that?" On taking it from his hand, I found that it contained tincture of tannin, a preparation much used for the teeth. I was somewhat startled by the suddenness of the question, and replied in the negative, on which the subject dropped. On my way home, however, I was again struck by the peculiarity of the Baron's manner in putting the question; and on thinking the matter over, the idea suddenly flashed across me that tannic acid was the antidote to antimony, and that the symptoms of poisoning by tartarised antimony, to which attention had just been drawn by Professor Taylor, in the case of the Rugely murder, closely resembled in many respects those under which Mrs. Anderton was then suffering. At the first moment this supposition seemed to account for all the mysterious part of the case; but on reflection the difficulty returned, for it seemed impossible that the poison could have been administered by any one but Mr. Anderton himself, and I felt it still more impossible to suspect him of such an act, in face of the evident and extreme affection existing between them. On mature reflection, however, I determined on trying, at all events for a time, the course suggested by the Baron, and accordingly exhibited large doses of Peruvian bark, together with other medicines of the same kind. My suspicions were at first increased by the improvement apparently effected by these remedies, and I took occasion to ask Mr. Anderton, in a casual way, in presence of the nurse and one of the servants, whether he had any emetic tartar or antimonial wine in the house. The manner of his reply entirely removed from my mind any idea that either of those present at least had any knowledge of such an attempt as seemed implied by the Baron, and on seeing that gentleman a day or two after, I questioned him as to the true bearing of his suggestion. He disclaimed, however, any such meaning as I had been disposed to attribute to his words, stating, in a general way, that he had before known great benefit to accrue from the exhibition of such medicines in similar cases, and expressing a hope that they might be successful in the present instance. Something, however, in his manner, and especially the great stress laid upon careful watching of the patient's diet while under this course of treatment, led me still to fancy that he was not so entirely without doubt as he wished me to believe; but that, on the contrary, his suspicions pointed towards Mr. Anderton, his friendship for whom made him desirous of concealing them. This opinion was confirmed by the recollection of another apparent instance of suspicion on the part of the Baron, to which, a few days previously, however, I had not at the time attached any importance. I accordingly continued the bark treatment, determining, should any fresh attack occur, to take measures for investigating the matter; for which purpose I gave private orders to the nurse, on whom I knew that I could thoroughly depend, to allow nothing to be removed from the room until I had myself seen the patient. The beneficial effects of the bark continued for about ten or twelve days, at the end of which period I was sent for hurriedly in the middle of the night, the disease having returned with greater violence than at any previous attack. Having done what was in my power to alleviate the immediate pressure of the symptoms, I took an opportunity of privately securing portions of the vomited and other matters, which I immediately had submitted to a searching chemical analysis. No trace, however, of antimony, arsenic, or any similar poison, could be detected, and as the tannic acid appeared now to have lost its remedial power, I came finally to the conclusion that its apparent efficacy had been due to some other unknown cause, and that the suspicions of the Baron were altogether without foundation. I continued the former treatment, varied from time to time as experience suggested, but without being able to arrest the progress of the disease, which I am inclined to think must have been constitutional in its character, and probably hereditary, as I learned from Mr. Anderton that the patient's mother had also died of some internal disease, the exact symptoms of which, however, he was unable to call to mind. Towards the close of the case the patient was almost constantly delirious from debility, and the immediate cause of death was entire prostration and exhaustion of the system. I wished Mr. Anderton to allow a post mortem examination, with a view to discovering the true nature of the disorder, but he seemed so extremely sensitive on the subject, and was in such a state of nervous depression, that I forbore to press the point. The Baron also seemed to discourage him from such an idea. Subsequently an order came for an inquest, and I then assisted at the analysis which followed, and which was performed by Mr. Prendergast. We found no traces of antimony in any part of the body or its contents. The report of Mr. Prendergast, in which I fully concurred, will show the result of the analysis. Looking at that, and at all the circumstances of the case, I was, and still am, convinced that Mr. Anderton was perfectly innocent of the crime imputed.

In answer to the queries forwarded at various times by Mr. Henderson, Dr. Dodsworth gives the following replies:

1. In questioning the Baron as to his suggestion respecting the tincture of tannin, I put it plainly to him whether he had been led to make it by any suspicion of poison. This he disclaimed with equal directness, but with such hesitation as convinced me that the suspicion was really in his mind.