полная версия

полная версияThe Notting Hill Mystery

3. —Extracts from Mrs. Anderton's Journal– Continued.

Jan. 20, 1855. – At last I get back once more to my old brown friend.[3] Dear old thing, how pleasant its old face seems! Very little to-day though; only a word or two, just to say it is done. Oh, how it tries one!

Jan. 25. – My own dear husband's birthday; and, thank Heaven! I am once more able to sit with him. Oh! how kind he has been through all these weary weeks, when I have been so fretful and impatient. Why should suffering make one cross? God knows, I have suffered. I never thought to live through that terrible night. It makes me shudder to think of it. And, then, that horrid, deathlike, leaden taste – that was worst of all. Well, thank God! I am better now, but so weak. I am quite tired with writing even these few lines…

Feb. 12. – How weak I still am! Walked out to-day with dear William for the first time upon the pier, but had scarcely got to the end of it, when I felt so tired I was obliged to sit down while poor William went to fetch a chair to take me home.

Feb. 13. I have been quite startled to-day. I was talking to Dr. Watson about my being so tired yesterday, and about how very weak I still was, and how ill I had been – and, at last, he let slip that, at the time, he thought I had been poisoned. It gave me quite a turn, and then he tried to make us talk of something else, but I could not get it out of my head, and kept coming back and back to it, and wondering who could have had any possible interest in poisoning poor me. And so we went on talking; and, at last, Dr. Watson said something which let out that at first he had suspected – William! my own William! my precious, precious husband! Oh! I thought I should have choked on the spot. I don't know what I said, but I do know I could not have said too much, and poor William tried to laugh it off, and said: "Who else would have gained anything by it? Would he not have had that miserable 25,000l.? and besides him, there was no one but the Charities in India, and they could not have done it, because they would not exist till we were gone;" but I could see how he winced at the idea, and I felt as though my blood were really boiling in my veins. And then that man – oh! how thankful I shall be when we can get away from him – tried to persuade me that he had not really thought it. I should think not, indeed! and that he soon saw it was impossible, and all that; and at last, I fairly burst out crying with passion, and ran out of the room. And – and – I could cry now to think of my poor dear Willie being – and I shall, too, if I go on thinking about it any longer, so I will write no more to-night.

Feb. 15. – No journal yesterday, I really could not trust myself to write. And poor Willie, though he tried to laugh at it, I could see how bitterly he felt the imputation. Good Heaven! think if that wretched man had really charged him with it. It would have killed him. I know it would, and he would rather have died a thousand times. Well, I must not think of it any more. Only, once more, thank Heaven! we shall soon be going away.

April 7. – Back once more at home, thank Heaven! But how slow, how very slow this convalescence, as they call it, is. Oh! shall I ever be well again, as I was last year before that horrid day at Dover!

May 3. – So we are to leave England for a time, and try the German baths. I am almost thankful for it. I have grown very fond, too, of this dear little luxurious house, though I could hardly say why. It is like my wonderful fancy for Rosalie. Ah, poor Rosalie! I wonder where she is now, and when they will return. I cannot help thinking she might do me some good. But, as I was saying; fond as I am of this dear little house, I shall be really glad to leave it for a time, and see what change of air will do for me. If I could only get rid of those terrible night perspirations. It is they that pull me down so, and make me so weak and miserable. Oh! what would I not give to be well once more, if it were only to get rid of the memory of that time.

July 7. – Safe at Baden Baden; and too early as yet for the majority of the English pleasure-seekers. What a delicious place it is; I declare I quite feel myself better already…

Sept. 11. – Really almost well again. Quite a comfortable talk to-day with dear Willie about that foolish Dr. Watson; the first time the subject has been mentioned between us, since that day when I got into such a passion about it. Poor man, he was hardly worth going into a rage about. We heard to-day of his having made some terrible blunder in the new place he has gone to, and lost all his practice by killing some poor old woman through it. It was this made us talk of his poisoning notion, and oh! how glad I was to see that dear Willie had quite got over his nervousness about it. We had quite a long talk; and, at last, he promised me faithfully never to say a word more about it to any one.

Oct. 10. – Home again at last, and in our own dear little house. And really I feel once more as well and strong as this time last year. Dear William, too, how happy he is; the shadow seems quite to have passed away. God grant it may not return.

Oct. 30. – An eventful day. All the morning at the Crystal Palace, and just as we returned who should walk in but the Baron R**! It was just a year since he left us, but he had not altered in the very least. I do not think that short, square figure, with the impenetrable rosy face, and the large white hands, and those wonderful great green eyes that you can so rarely catch, and when you have caught, so invariably wish you had let alone, can ever change. I am afraid I was not very cordial to him. I ought to be, for he has done great things for me; and yet somehow when I saw him, I felt quite a cold shudder run all through me. Dear William saw it, and asked if I was ill, and when I laughed and said, "No, it was only some one walking over my grave," I could not help fancying that for a moment the Baron's lips seemed to turn quite white, and I just caught one glance from those awful eyes that seemed as if it would read me through and through. And yet after all it may have been only fancy, for the next moment he was talking in his rich, quiet voice as though nothing could ever disturb him. So Rosalie is gone. That is clear at all events, though what has exactly become of her I cannot quite so well understand. From all I can make out, she seems, poor girl, to have married very foolishly, and it was that that was the matter between them when they went away last year. The Baron seemed indeed to hint at something even worse, but he would not speak out plainly, and I would defy any one to make that man say one word more than he may choose. Poor Rosalie, I hope she has not come to any harm.

Nov. 1. – Another visit from the Baron, to say good-bye before his return to – his wife! How strange that we should never have heard of her before, and even now I cannot make out whether he has married since he left us or whether he was always so. Certainly that man is a mystery, and just now it pleases him to talk especially in enigmas. He does not seem disposed, however, to put up with vague information on our part. I thought he would never have done questioning poor William and me about my illness, and at last he drew it out of me – not out of William, dear fellow – what that foolish Dr. Watson had said. After all I am not sorry I told him, for it was quite a relief to hear him speak so strongly of the absurdity of such an idea, and I am sure it was a comfort to poor William. He – the Baron – spoke very strongly too about the danger of setting such ideas about, and particularly cautioned dear Willie not to mention it to any one. I knew he would not have done so any way, but this will make him more comfortable.

April 3. – Such a delightful day and so tired. I never saw Richmond look so lovely, and how dear Willie and I did enjoy ourselves in that lovely park. But oh! I am so sleepy. Not a word more.

April 5. – Another lovely day – strolling about Lord Holland's Park all the morning, and this evening some music in our own dear little drawing-room. How happy – how very happy – good Heaven, what is this? That old horrible leaden taste: and oh, so deadly sick…

April 6. – Thank Heaven the attack seems to have passed away. Oh, how it frightened me. Thank Heaven, too, I was able to keep the worst from dear William, and he did not know how like it was to that other dreadful time.

April 20. – Again that horrible sickness, and worse – oh, far worse – still, that awful deadly leaden taste. Worse this time, too, than the last. In bed all day yesterday. Poor Willie terribly anxious. Pray Heaven it may not come again.

May 6. – Another attack. God help me! if this should go on, I do not know what will become of me. Already I am beginning to feel weaker and weaker. Poor Willie! – these last three days have been terrible ones for him. However, the doctor says it will all pass off. Pray Heaven it may!

May 25. – More sickness, more derangement, more of that horrible leaden taste. The doctor himself is beginning to look uncomfortable, and I can see that poor Willie's mind is reverting to that terrible suggestion a year ago. Thank Heaven I have as yet managed to conceal from him and from Dr. Dodsworth that horrid deadly taste which made such an impression on Dr. Watson. Oh, when will this end!

June 10. – A horrible suspicion is taking possession of me. What can this mean? I look back through my journal, and it is every fortnight that this fearful attack returns. The 5th and 18th of April – 3rd and 21st of May – and now again the 7th of this month. And that terrible leaden taste which is now almost constantly in my mouth; and with every attack my strength failing – failing – O God, what can it be?

June 26. – Another fortnight – another attack. There must be foul play somewhere. And yet who could – who would do such a thing? Thank Heaven I have still concealed from my poor William that worst symptom of all, the horrible leaden taste which is now never out of my mouth. My precious Willie, how kind, how good he is to me…

July 12. – I cannot hold out much longer now. Each time the attack returns I lose something of the little, the very little strength that is left. God help me, I feel now that I must go… The Baron came to-day, and for a moment my poor boy's face lighted up with hope again. They had a long discussion before the doctor would consent to consult with him, but after that, they seemed to change the medicines. But something must have gone wrong, for I have never seen Dr. Dodsworth look so grave.

Aug. 1. – I think the end is drawing very near now. This last attack has weakened me more than ever, and I write this in my bed. I shall never rise from it again. My poor, poor Willie… Three days I have been in bed now, but I have taken nothing from any hand but his.

Aug. 17. – This is, I think, almost the last entry I shall make. Another fortnight and I shall be too weak to hold the pen – if, indeed, I am still here.

Sept. 5. – Another attack. Strange how this weary body bears up against all this pain. Would that it were over; and yet my poor, poor boy… He too, is almost worn out; night and day he never leaves me… I take the things from his hand, but I cannot taste them now – nothing but lead…

Sept. 27.11– Farewell my husband – my darling – my own precious Willie. Think of me – come soon to me. God bless you – God comfort you – my darling – my own.

In the hand of Mr. Anderton.This day my darling died.

Oct. 12th, 1856.

W. A.

SECTION IV

1. —Memorandum by Mr. Henderson.

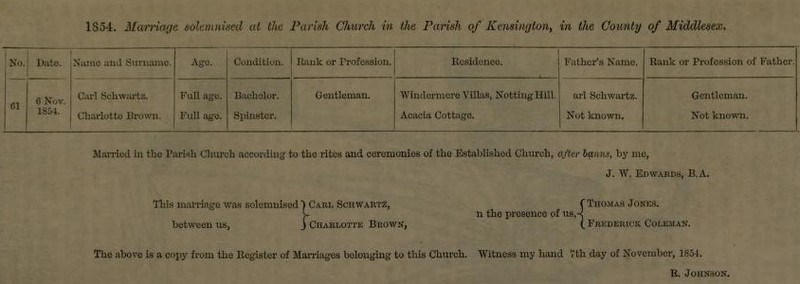

In the following certificate12 you will perceive that the lady is described as of "Acacia Cottage, Kensington." The identity of the name with that given by both Julie and Leopoldo, as the proper designation of the Baron's "medium," confirmed my suspicion that it was in fact to the girl Rosalie that the Baron was married under that name, notwithstanding the strong opinion of Julie as to the impossibility of such being the case. Still, however, it was possible that this might, after all, be a mere coincidence; and I therefore proceeded to make such inquiries as seemed most likely to elucidate the point. I had considerable difficulty in finding the house, which two or three years back was included in the regular numbering of the row of similar tenements in which it stands; but I at last succeeded in identifying it. I found the landlady a very deaf old person, whose memory was evidently failing, and was at first unable to extract from her any kind of information on the subject, except that "she had had a great many lodgers, and couldn't be expected to know all about all of them." In the course of a second visit, however, I succeeded in persuading her to favour me with a sight of her books, and looking back to October and November, 1854, I found the sum of 2l. 5s., entered as payment from Miss C. Brown of three weeks' rent, from the 18th October to the 8th November.13 On further examining the books, I found that at this time, while the other lodger was charged sundry sums for fire, Miss Brown, though occupying the principal sitting-room, had no fire at all during the whole time of her tenancy, though the commencement of November in that year was unusually cold. There were also sundry other little charges invariable in the other cases, but omitted in the case of Miss Brown; and at length, on these things being pointed out to her, the old lady managed to remember that the rooms had been taken by a gentleman for a lady who was to give lessons in drawing. The gentleman had paid the three weeks' rent in advance, and had specially requested that they might be kept vacant for her, as the time of her arrival was uncertain. He had also begged that any letters or messages received for her should be sent to a certain address immediately. After a great deal of searching, this address was at length found, and proved to be the square glazed card which I enclose.

2. Letters or messages for Miss Brown to be forwarded immediately to care of

Baron R**,

Post Office, Notting Hill.The old lady further stated that she never saw the gentleman again, and that she had never seen the lady at all. In fact, after payment of the money, nothing further had been heard of either of the parties concerned; and as no inquiries had been made for Miss Brown, the subject had altogether passed from her mind.

Being thus pretty well satisfied of the identity of Madame R**, my next care was to trace the proceedings of the Baron between the time of his marriage and the death of his wife, which took place, as you are aware, in London, about two years and a half subsequently; the insurances having, as you well know, been effected at about the middle of this period. The information afforded me by Dr. Jones, the medical man who signed the certificate to your office in connection with the policy on the life of Madame R**, first gave me the required clue, and you will, I think, find in the depositions immediately following, sufficient, at all events, to justify, if not entirely to corroborate, the suspicions which first gave rise to my inquiries. It is certainly unfortunate that here, too – as in the case of Mr. Aldridge, whose letter first aroused these suspicions – the witness on whose evidence the principal stress must be laid, is not one whose testimony would probably carry much weight with a jury. Such, however, as it is, I have felt it my duty to lay it before you; and I will now leave it, with such other as I have been able to collect, to tell its own tale.

3.– Statement of Mrs. Whitworth.

My name is Jane Whitworth. I am a widow, and gain my living by letting furnished apartments at Bognor, Sussex. The principal season at Bognor is during the Goodwood races, and there are very few visitors there in the autumn and winter. On the 6th October, 1854, I let the whole upper part of my house to a lady and gentleman, who arrived there late that evening. They gave some foreign name; I forget what. It was some long German name. They did not give the name at first. Not till I asked for it. I don't know that the gentleman was particularly unwilling. I said I wanted it for my bill; and he laughed, and said it did not matter, – anything would do. Then I said, if letters came, and he said: – "Oh! there won't be any letters," and went on reading the paper. I went down stairs, and as I was going down he rang, and I went back, and he told me of his own accord. That was at the end of the first week when I was making out my bill. They said they intended remaining for some weeks. It was the gentleman who said this. The lady took no part in the business, and seemed out of spirits, and very much afraid of her husband. He settled with me to take the apartments at thirty shillings a week. He was to remain as long as he liked. Not beyond the next race week, of course. We never let over the race week. He also made an agreement with me about board. I was to find for him and the lady, and the servant, for 2l. 15s. a week. That was without wine, beer, or spirits. It is not a usual arrangement. We do it sometimes – not often. The gentleman said it was because his wife was not well, and could not be troubled. The servant was his. It was a maid. She did not come with them. The gentleman hired her at Brighton. That is not a usual arrangement. Certainly not. I never made such a one before, and I told him so. He said it was because he was so particular about his servants. He said he never would live where the servants were not under his own hand – where he could not turn them away. I said I did not like it, it was not the custom. He said he was sorry, but he could not take the apartments without it, and then I gave way. Afterwards he followed me down stairs, and gave me to understand it was something about his wife. At first, I thought she was not quite right in her head. That was from what he told me. I said I should be afraid to have her in the house, but he laughed, and said it was not that. I then supposed it must be temper. He was very pleasant about it. He was always very pleasant to me. I don't know what he may have been to other people. I always had my money to the day, and he was always pleasant. I can't say better than that. He got a servant a few days after they came. I did not turn away my own. I had none at the time. The season being over, it was a great chance whether I let again, and I sent my servant away, and did for myself. A charwoman did for the gentleman till he got a servant. He got one from Brighton. I recommended two or three in Bognor, but they did not suit. The one he got was a girl about twenty. Her name was Sarah Something. I did not think much of her. I used sometimes to think my tea and sugar went very fast. I never caught her taking anything. She was very quiet and civil-spoken. She stayed with the gentleman about a month; not quite. She was sent away for giving the lady a dose of physic in her arrow-root to make her sick. The lady was very bad indeed. We thought she would have died. She was dreadfully sick, and had the cholera awfully bad. This was the 9th of December.14 I know it from my books. The gentleman sent out for brandy and several things, and they are down in my book. On the following morning he sent for some stuff from the chemist.15 Before that he had given her some medicine himself. I don't know what it was. He had a lot of chemicals and things. He kept them in a back room. The lady had a doctor. Not at first. Not till the Monday after she was ill. I asked him to send for one, but he said he was a doctor himself. She continued very ill, and on the Sunday night I asked him again. He said if she was not better next morning, he would. I wanted him to send for Dr. Pesketh or Dr. Thompson, but he would not. He said they were no good. I have always heard them very highly spoken of. Dr. Pesketh I have always heard of as a first-rate doctor. He is since dead. Dr. Thompson is a very good doctor, too; but Dr. Pesketh, perhaps, had most practice. I don't think the gentleman knew anything about either of them. He sent for a Doctor Jones, who was in lodgings in the Steyne. I believe he lived in London. He prescribed for the lady while he stayed in Bognor. He went away the week after. He was only there a fortnight. The gentleman heard of him through a friend of mine in the Steyne. He asked me to find out whether there was no London doctor in the place. He would not have any one who belonged to the place. He said country doctors were no good. The lady got better, but very slowly. She was ill several weeks. When she was strong enough they went away. He was very attentive to her. Never left her alone for a minute hardly. She did not seem very fond of him. I think she was afraid of him, but I don't know why. He was very kind to her, and always particularly civil. Sometimes she seemed quite put out like by his civility. I thought sometimes she would have flown out at him. She never did fly out. He always seemed able to stop her. I don't know how he did it. He never said anything; only looked at her; but it was quite enough. I thought she must have been doing something wrong, and he had brought her to Bognor to be out of the way. I do not know exactly what made me think so. It was the way they went on, and what he said to me. He never told me so. It was from things he said. I did not talk much to the lady. I thought her very ungrateful when he was so kind. Then she was hardly ever alone. Only once when the gentleman went out for something. Then she was left about an hour. She was writing part of the time. She borrowed writing materials of me. There were none in the sitting-room. There usually were, but the gentleman had sent the inkstand downstairs. He said it was sure to be upset. I lent the lady the things, and she gave me two letters for the post. She did not say anything to me; only asked me to post them immediately. One was addressed to Notting Hill. I noticed that because I have a sister living there; the other was to some theatre. I forget where. It struck me, because I thought it odd that a lady should write to a theatre. I didn't think it was right. I would rather not say what I thought. Well, it was that she was connected with some one there. Improperly, of course. The letter was not addressed to a man. It was "Miss Somebody," but that might be a blind. I thought this might account for her behaviour to her husband. I was very angry. A woman has no business to go on so. It is particularly bad when she has such a good husband. I did not say this to her. I did not notice the address till I got down-stairs. I kept the letters, and told the gentleman when he came in. He seemed very much vexed. He took the letters, and was very much obliged to me. He put the letter to the theatre into the fire without opening it. The other he said he would post himself. I don't know whether he did post it, or not. I suppose so, of course. I think he spoke to the lady about it. I am sure he did, for that night when I went up, I could see she had been crying, and she would never speak to me again. She spoke English quite well. The letters were addressed in English. When she spoke to the gentleman it was generally in some foreign language, but she could speak English perfectly. I do not know what became of the girl, Sarah. I think she went into service again at Brighton. I know the gentleman gave her a character. He was very kind to her. He was always very kind. He was the pleasantest and most civil-spoken gentleman I ever met, and I think his wife behaved very bad to him.

4. Statement of Dr. Jones, of Gower Street, Bedford Square.16

I am a physician, residing in Gower Street, Bedford Square. In the beginning of December, 1854, I was suffering from a severe cold, and being unable to shake it off, went for a fortnight to the sea for change of air. I selected Bognor, because I had been in the habit of spending my holidays there for two or three years. I was lodging in the Steyne. Some few days after my arrival, I received a message requesting me to call and see a lady who was dangerously ill at a lodging in another part of the town. At first I declined to go, not wishing to interfere with the established practitioners of the place. A gentleman then called upon me, who gave the name of the Baron R**. He informed me that the lady in question was his wife, and that she was dangerously ill from the effects of a considerable quantity of emetic tartar, administered to her by the maid. He was very urgent with me to attend, saying that he was in the greatest anxiety about his wife, and that he could not in such a case sufficiently rely upon the skill of any country doctor. He pressed me so strongly, that I at length consented to accompany him to his lodgings. I found the patient in a very exhausted condition, and evidently suffering from the effects of some irritant poison. From what the Baron told me, the symptoms were much abated, but the purging still continued, accompanied with severe griping pains and profuse perspirations. I learned from the Baron that, being himself a good amateur chemist, and having accidentally discovered at the outset the origin of his wife's illness, he had so far treated her himself, rather than trust to the chance of a country physician. He described his treatment, which appeared to me perfectly correct. On becoming satisfied of the cause of the disturbance, he first promoted vomiting as much as possible by the exhibition of tepid water, and afterwards of warm water, with a small quantity of mustard. When no more food appeared to be left in the stomach, he then administered large quantities of a saturated infusion of green tea, of which he had a few pounds at hand for his own drinking, and, finally, at the time of my arrival was exhibiting considerable doses of decoction of Peruvian bark: both which remedies are recommended by Professor Taylor in cases of antimonial poisoning. Their action left no doubt on my mind as to the origin of the symptoms; but by desire of the Baron I proceeded to analyse with him portions of the vomited and excreted matter, as also a portion of the arrow-root in which the tartarised antimony was supposed to have been administered. To all of these we together applied the usual tests, – viz., nitric acid, ferrocyanide of potassium, and hydrosulphuret of ammonia, – and succeeded in ascertaining beyond doubt the presence of antimony in all three. The quantity, however, appears to have been small. So far as we could ascertain, there could not have been more than one, or at the most two grains of tartarised antimony in the arrow-root, of which not much more than three parts was eaten. I cannot account for the violent action of so small a quantity. I have frequently administered much larger doses in cases of inflammation of the lungs without ill effect. Two grains is by no means an unusual dose when intended to act as an emetic; but the action of antimony varies greatly with different constitutions. Having certified ourselves of the presence of the suspected poison, the question was, as to the person by whom it had been administered. The Baron said he had no doubt that it was a trick on the part of the servant maid, between whom and her mistress there had been some dispute a few days since. We therefore determined on taxing her with it; but before doing so, proceeded to examine a bottle of prepared tartar emetic, which, as the Baron informed me, he kept for his own use, being subject to digestive derangement. He was, I believe, addicted to the pleasures of the table, and was in the habit of taking an occasional emetic. The bottle was not in its usual place, but was standing on the table at the side of the dressing-case in which it was usually kept. It was labelled, "The emetic. One tea-spoonful to be taken as directed." I remarked that it should be labelled "poison," and the Baron quite agreed with me, and immediately wrote the word in large characters on a piece of paper and gummed it round the bottle. We then weighed the contents of the bottle, from which three doses only had been taken by the Baron, and, on comparing the results, we found that a quantity equivalent to about one grain and a-half of the tartarised antimony had been abstracted in excess of this amount. The servant maid was the only person besides the Baron who usually had access to the apartment; and we at once sent for her and taxed her with having administered it to Madame R** in the arrow-root before mentioned. My own counsel was to give her immediately in charge, but the Baron pointed out, very justly, that there was nothing to show the girl that she was doing anything that could possibly affect life; and that, in the absence of any motive for such a crime, it was only fair to conclude that nothing was intended beyond a foolish practical joke. He said the same to the girl, and spoke to her very kindly indeed. At first she altogether denied it, and pretended to be quite astonished at such an imputation. The Baron, however, looked steadily at her and said, "Take care, Sarah! Remember what I said to you only three days ago." She did not attempt then to deny it any longer, but said she was very sorry, but she hoped the Baron would forgive her. The Baron said he could not possibly retain her in his service, and she then begged of him not to send her away without a character. At this time I interfered, and said he would be very wrong to send her into any other family after playing such a trick. She again protested she had meant no harm, and the subject then dropped, the Baron saying he would take time to consider of it. From that time I attended Madame R** until my return to London, when she was clearly recovering. I did not enter into any conversation with her, as she seemed very reserved and of an unsociable disposition. The Baron seemed an unusually attentive husband. Talking over the subject of the seizure a day or two afterwards, he informed me that the death of his wife would also have been a severe loss in a pecuniary point of view, as if she lived she would inherit a considerable fortune. I asked him why he did not insure her life, and he said he should now certainly do so, but had not before thought of it. He called upon me about two months later, in passing through town, and informed me that he intended to travel abroad for some months. I recommended the German baths, and on his objecting to the crowds of English there, suggested Griesbach or Rippoldsau, in the Black Forest, where Englishmen are rarely to be encountered. It was too early for either place at that time, and I recommended the south of France until the season was sufficiently advanced. I did not see him again till October, 1855, when he again called upon me with Madame R**, who seemed perfectly restored, and of whom I had no difficulty in reporting most favourably to the – Life Assurance Association, as also some weeks later to the – Life Office of Dublin, when applied to for my professional opinion. I think Madame R**'s was an excellent life, and there could be no better proof of it than her entire recovery in the course of a very few months, or indeed weeks, from so severe an illness. The sensitiveness to antimony would not affect this opinion. Indeed Professor Taylor, in his work on poisons, points out distinctly the "idiosyncratic" action of antimony and other medicinals on certain constitutions, as "conferring on an ordinary medicinal dose a poisonous instead of a curative action." I have a copy of his work now before me, in which he says that "daily experience teaches us that some persons are more powerfully affected than others by an ordinary dose of opium, arsenic, antimony, and other substances;" and again, in considering the probable amount of the "fatal dose," he speaks of "that ever-varying condition of idiosyncracy, in which, as it is well known, there is a state of constitution more liable to be affected by antimonial compounds than other individuals apparently in the same conditions as to health, age," &c. I did not, therefore, nor do I now, consider the sensitiveness of Madame R**'s constitution to that medicine any objection to her life, especially in view of the immense vitality shown by her recovery. With regard to the sleep-walking, I have had no hint from the Baron of such a propensity on the part of Madame R**. Certainly it was never suggested that she could have poisoned herself in that way. Indeed the servant girl admitted the act. The mode of Madame R**'s death does not in any degree shake my confidence in my former opinion, as such an occurrence might have happened, though by no means likely to do so, to any one in the habit of walking in their sleep, a propensity which in Madame R**'s case I had no means of ascertaining. I have been enabled to be thus precise in my statement, from the fact that the interesting nature of the case led me to make a special memorandum of it in my diary, from which the above is taken. I shall therefore have no difficulty in confirming any portion of it upon oath.