полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

The six or eight thousand years which the various interpreters of the Biblical record assign for the creation of the world and the duration of man upon the earth, allow little enough space for the development of his civilization – a civilization which documental evidence carries almost to the verge of the limit – for the expansion and divergence of stocks, or the obliteration of the branches connecting them.

But, fortunately, we are no more compelled to fetter our belief within such limits as regards man than to suppose that his appearance on the globe was coeval with or immediately successive to its own creation at that late date. For while geological science, on the one hand, carries back the creation of the world and the appearance of life upon its surface to a period so remote that it is impossible to estimate it, and difficult even to faintly approximate to it, so, upon the other, the researches of palæontologists have successively traced back the existence of man to periods variously estimated at from thirty thousand to one million years – to periods when he co-existed with animals which have long since become extinct, and which even excelled in magnitude and ferocity most of those which in savage countries dispute his empire at the present day. Is it not reasonable to suppose that his combats with these would form the most important topic of conversation, of tradition, and of primitive song, and that graphic accounts of such struggles, and of the terrible nature of the foes encountered, would be handed down from father to son, with a fidelity of description and an accuracy of memory unsuspected by us, who, being acquainted with reading and writing, are led to depend upon their artificial assistance, and thus in a measure fail to cultivate a faculty which, in common with those of keenness of vision and hearing, are essential to the existence of man in a savage or semi-savage condition?30

The illiterate backwoodsman or trapper (and hence by inference the savage or semi-civilized man), whose mind is occupied merely by his surroundings, and whose range of thought, in place of being diffused over an illimitable horizon, is confined within very moderate limits, develops remarkable powers of observation and an accuracy of memory in regard to localities, and the details of his daily life, surprising to the scholar who has mentally to travel over so much more ground, and, receiving daily so many and so far more complex ideas, can naturally grasp each less firmly, and is apt to lose them entirely in the haze of a period of time which would still leave those of the uneducated man distinguishable or even prominent landmarks.31 Variations in traditions must, of course, occur in time, and the same histories, radiating in all directions from centres, vary from the original ones by increments dependent on proportionately altered phases of temperament and character, induced by change of climate, associations and conditions of life; so that the early written history of every country reproduces under its own garb, and with a claim to originality, attenuated, enriched, or deformed versions of traditions common in their origin to many or all.32

Stories of divine progenitors, demigods, heroes, mighty hunters, slayers of monsters, giants, dwarfs, gigantic serpents, dragons, frightful beasts of prey, supernatural beings, and myths of all kinds, appear to have been carried into all corners of the world with as much fidelity as the sacred Ark of the Israelites, acquiring a moulding – graceful, weird or uncouth – according to the genius of the people or their capacity for superstitious belief; and these would appear to have been materially affected by the varied nature of their respective countries. For example, the long-continuing dwellers in the open plains of a semi-tropical region, relieved to a great extent from the cares of watchfulness, and nurtured in the grateful rays of a genial but not oppressive sun, must have a more buoyant disposition and more open temperament than those inhabiting vast forests, the matted overgrowth of which rarely allows the passage of a single ray, bathes all in gloom, and leaves on every side undiscovered depths, filled with shapeless shadows, objects of vigilant dread, from which some ferocious monster may emerge at any moment. Again, on the one hand, the nomad roaming in isolation over vast solitudes, having much leisure for contemplative reflection, and on the other, the hardy dwellers on storm-beaten coasts, by turns fishermen, mariners, and pirates, must equally develop traits which affect their religion, polity, and customs, and stamp their influences on mythology and tradition.

The Greek, the Celt, and the Viking, descended from the same Aryan ancestors, though all drawing from the same sources their inspirations of religious belief and tradition, quickly diverged, and respectively settled into a generous martial race – martial in support of their independence rather than from any lust of conquest – polite, skilled, and learned; one brave but irritable, suspicious, haughty, impatient of control; and the last, the berserker, with a ruling passion for maritime adventure, piracy, and hand-to-hand heroic struggles, to be terminated in due course by a hero’s death and a welcome to the banqueting halls of Odin in Walhalla.

The beautiful mythology of the Greek nation, comprising a pantheon of gods and demigods, benign for the most part, and often interesting themselves directly in the welfare of individual men, was surely due to, or at least greatly induced by, the plastic influences of a delicious climate, a semi-insular position in a sea comparatively free from stormy weather, and an open mountainous country, moderately fertile. Again, the gloomy and sanguinary religion of the Druids was doubtless moulded by the depressing influences of the seclusion, twilight haze, and dangers of the dense forests in which they hid themselves – forests which, as we know from Cæsar, spread over the greater part of Gaul, Britain, and Spain; while the Viking, having from the chance or choice of his ancestors, inherited a rugged seaboard, lashed by tempestuous waves and swept by howling winds, a seaboard with only a rugged country shrouded with unsubdued forests at its back, exposed during the major portion of the year to great severity of climate, and yielding at the best but a niggard and precarious harvest, became perforce a bold and skilful mariner, and, translating his belief into a language symbolic of his new surroundings, believed that he saw and heard Thor in the midst of the howling tempests, revealed majestic and terrible through rents in the storm-cloud. Pursuing our consideration of the effects produced by climatic conditions, may we not assume, for example, that some at least of the Chaldæans, inhabiting a pastoral country, and being descended from ancestors who had pursued, for hundreds or thousands of years, a nomadic existence in the vast open steppes in the highlands of Central Asia, were indebted to those circumstances for the advance which they are credited with having made in astronomy and kindred sciences. Is it not possible that their acquaintance with climatology was as exact or even more so than our own? The habit of solitude would induce reflection, the subject of which would naturally be the causes influencing the vicissitudes of weather. The possibilities of rain or sunshine, wind or storm, would be with them a prominent object of solicitude; and the necessity, in an unfenced country, of extending their watch over their flocks and herds throughout the night, would perforce more or less rivet their attention upon the glorious constellations of the heavens above, and lead to habits of observation which, systematized and long continued by the priesthood, might have produced deductions accurate in the result even if faulty in the process.

The vast treasures of ancient knowledge tombed in the ruins of Babylon and Assyria, of which the recovery and deciphering is as yet only initiated, may, to our surprise, reveal that certain secrets of philosophy were known to the ancients equally with ourselves, but lost through intervening ages by the destruction of the empire, and the fact of their conservancy having been entrusted to a privileged and limited order, with which it perished.33

We hail as a new discovery the knowledge of the existence of the so-called spots upon the surface of the sun, and scientists, from long-continued observations, profess to distinguish a connection between the character of these and atmospheric phenomena; they even venture to predict floods and droughts, and that for some years in anticipation; while pestilences or some great disturbance are supposed to be likely to follow the period when three or four planets attain their apogee within one year, a supposition based on the observations extended over numerous years, that similar events had accompanied the occurrence of even one only of those positions at previous periods.

May we not speculate on the possibility of similar or parallel knowledge having been possessed by the old Chaldæan and Egyptian priesthood; and may not Joseph have been able, by superior ability in its exercise, to have anticipated the seven years’ drought, or Noah, from an acquaintance with meteorological science, to have made an accurate forecast of the great disturbances which resulted in the Deluge and the destruction of a large portion of mankind?34

Without further digression in a path which opens the most pleasing speculations, and could be pursued into endless ramifications, I will merely, in conclusion, suggest that the same influences which, as I have shown above, affect so largely the very nature of a people, must similarly affect its traditions and myths, and that due consideration will have to be given to such influences, in the case of some at least of the remarkable animals which I propose to discuss in this and future volumes.

Chronological List of some Authors writing on, and Works relating to Natural History, to which References are made in the present Volume; extracted to a great extent, as to the Western Authors, from Knight’s “Cyclopædia of Biography.”

The Shan Hai King– According to the commentator Kwoh P’oh (A.D. 276-324), this work was compiled three thousand years before this time, or at seven dynasties’ distance. Yang Sun of the Ming dynasty (commencing A.D. 1368), states that it was compiled by Kung Chia (and Chung Ku?) from engravings on nine urns made by the Emperor Yü, B.C. 2255. Chung Ku was an historiographer, and at the time of the last Emperor of the Hia dynasty (B.C. 1818), fearing that the Emperor might destroy the books treating of the ancient and present time, carried them in flight to Yin.

The ’Rh Ya– Initiated according to tradition, by Chow Kung; uncle of Wu Wang, the first Emperor of the Chow dynasty, B.C. 1122. Ascribed also to Tsze Hea, the disciple of Confucius.

The Bamboo Books– Containing the Ancient Annals of China, said to have been found A.D. 279, on opening the grave of King Seang of Wei [died B.C. 295]. Age prior to last date, undetermined. Authenticity disputed, favoured by Legge.

Confucius– Author of Spring and Autumn Classics, &c., B.C. (551-479).

Ctesias– Historian, physician to Artaxerxes, B.C. 401.

Herodotus– B.C. 484.

Aristotle– B.C. 384.

Megasthenes– About B.C. 300. In time of Seleucus Nicator. His work entitled Indica is only known by extracts in those of Strabo, Arrian, and Ælian.

Eratosthenes– Born B.C. 276. Mathematician, Astronomer, and Geographer.

Posidonius– Born about B.C. 140. Besides philosophical treatises, wrote works on geography, history, and astronomy, fragments of which are preserved in the works of Cicero, Strabo, and others.

Nicander– About B.C. 135. Wrote the Theriaca, a poem of 1,000 lines, in hexameter, on the wounds caused by venomous animals, and the treatment. Is followed in many of his errors by Pliny. Plutarch says the Theriaca cannot be called a poem, because there is in it nothing of fable or falsehood.

Strabo– Just before the Christian era. Geographer.

Cicero– Born B.C. 106.

Propertius (Sextus Aurelius) – Born probably about B.C. 56.

Diodorus Siculus– Wrote the Bibliotheca Historica (in Greek), after the death of Julius Cæsar (B.C. 44). Of the 40 books composing it only 15 remain, viz. Books 1 to 5 and 11 to 20.

Juba– Died A.D. 17. Son of Juba I., King of Numidia. Wrote on Natural History.

Pliny– Born A.D. 23.

Lucan– A.D. 38. The only work of his extant is the Pharsalia, a poem on the civil war between Cæsar and Pompey.

Ignatius– Either an early Patriarch, A.D. 50, or Patriarch of Constantinople, 799.

Isidorus– Isidorus of Charaux lived probably in the first century of our era. He wrote an account of the Parthian empire.

Arrian– Born about A.D. 100. His work on the Natural History, &c. of India is founded on the authority of Eratosthenes and Megasthenes.

Pausanias– Author of the Description or Itinerary of Greece. In the 2nd century.

Philostratus– Born about A.D. 182.

Solinus, Caius Julius– Did not write in the Augustan age, for his work entitled Polyhistor is merely a compilation from Pliny’s Natural History. According to Salmasius, he lived about two hundred years after Pliny.

Ælian– Probably middle of the 3rd century A.D. De Naturâ Animalium. In Greek.

Ammianus Marcellinus– Lived in 4th century.

Cardan, Jerome A.– About the end of 4th century A.D.

Printing invented in China, according to Du Halde, A.D. 924. Block-printing used in A.D. 593.

Marco Polo– Reached the Court of Kublai Khan in A.D. 1275.

Mandeville, Sir John de– Travelled for thirty-three years in Asia dating from A.D. 1327. As he resided for three years in Peking, it is probable that many of his fables are derived from Chinese sources.

Printing invented in Europe by John Koster of Haarlem, A.D. 1438.

Scaliger, Julius Cæsar– Born April 23rd, 1484. Wrote Aristotelis Hist. Anim. liber decimus cum vers. et comment. 8vo. Lyon, 1584, &c.

Gesner– Born 1516. Historiæ Animalium, &c.

Ambrose Paré– Born 1517. Surgeon.

Belon, Pierre– Born 1518. Zoologist, Geographer, &c.

Aldrovandus– Born 1552. Naturalist.

Tavernier, J. B.– Born 1605.

Păn Ts’ao Kang Muh– By Li Shê-chin of the Ming dynasty (A.D. 1368-1628).

Yuen Kien Léi Han– A.D. 1718.

CHAPTER I.

ON SOME REMARKABLE ANIMAL FORMS

The reasoning upon the question whether dragons, winged snakes, sea-serpents, unicorns, and other so-called fabulous monsters have in reality existed, and at dates coeval with man, diverges in several independent directions.

We have to consider: —

1. – Whether the characters attributed to these creatures are or are not so abnormal in comparison with those of known types, as to render a belief in their existence impossible or the reverse.

2. – Whether it is rational to suppose that creatures so formidable, and apparently so capable of self-protection, should disappear entirely, while much more defenceless species continue to survive them.

3. – The myths, traditions, and historical allusions from which their reality may be inferred require to be classified and annotated, and full weight given to the evidence which has accumulated of the presence of man upon the earth during ages long prior to the historic period, and which may have been ages of slowly progressive civilization, or perhaps cycles of alternate light and darkness, of knowledge and barbarism.

4. – Lastly, some inquiry may be made into the geographical conditions obtaining at the time of their possible existence.

It is immaterial which of these investigations is first entered upon, and it will, in fact, be more convenient to defer a portion of them until we arrive at the sections of this volume treating specifically of the different objects to which it is devoted, and to confine our attention for the present to those subjects which, from their nature, are common and in a sense prefatory to the whole subject.

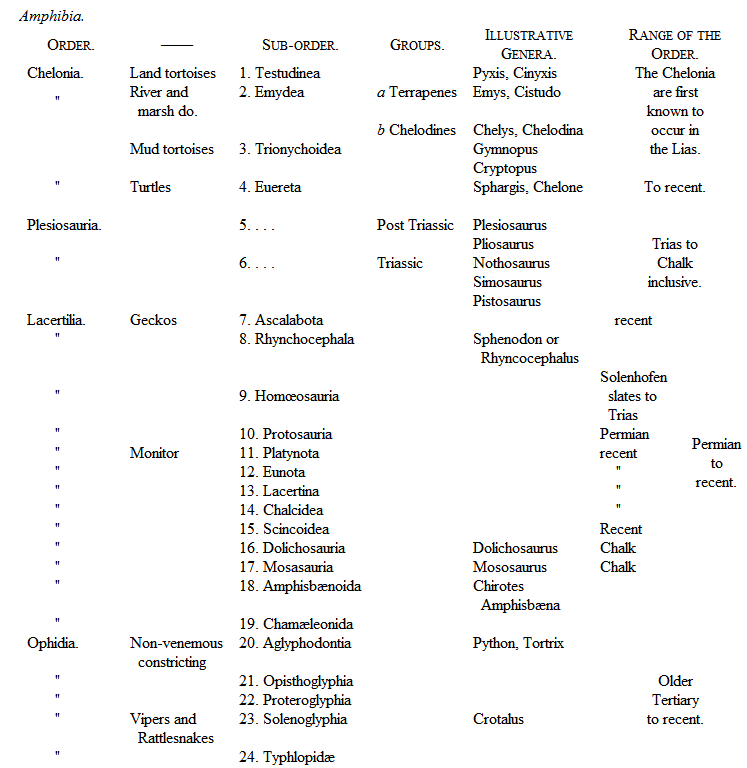

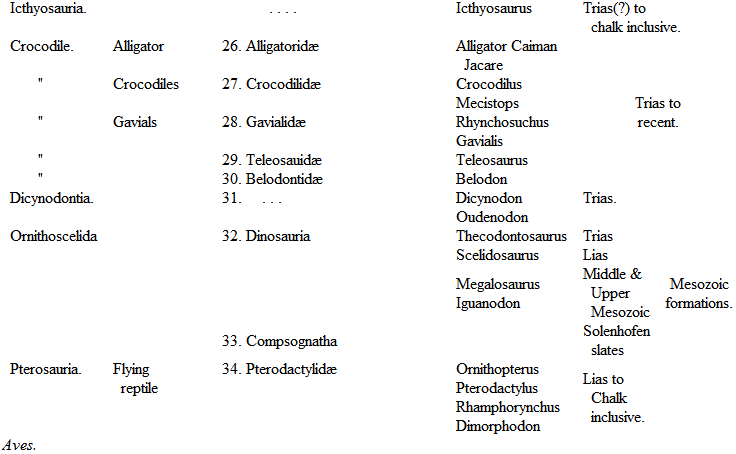

I shall therefore commence with a short examination of some of the most remarkable reptilian forms which are known to have existed, and for that purpose, and to show their general relations, annex the accompanying tables, compiled from the anatomy of vertebrated animals by Professor Huxley: —

REPTILES CLASSIFIED BY HUXLEY.

The most bird-like of reptiles, the Pterosauria, appear to have possessed true powers of flight; they were provided with wings formed by an expansion of the integument, and supported by an enormous elongation of the ulnar finger of the anterior limb. The generic differences are based upon the comparative lengths of the tail, and upon the dentition. In Pterodactylus (see Fig. 2, p. 18), the tail is very short, and the jaws strong, pointed, and toothed to their anterior extremities. In Rhamphorynchus (see Fig. 8, p. 18), the tail is very long and the teeth are not continuous to the extremities of the jaws, which are produced into toothless beaks. The majority of the species are small, and they are generally considered to have been inoffensive creatures, having much the habits and insectivorous mode of living of bats. One British species, however, from the white chalk of Maidstone, measures more than sixteen feet across the outstretched wings; and other forms recently discovered by Professor Marsh in the Upper Cretaceous deposits of Kansas, attain the gigantic proportions of nearly twenty-five feet for the same measurements; and although these were devoid of teeth (thus approaching the class Aves still more closely), they could hardly fail, from their magnitude and powers of flight, to have been formidable, and must, with their weird aspects, and long outstretched necks and pointed heads, have been at least sufficiently alarming.

We need go no farther than these in search of creatures which would realise the popular notion of the winged dragon.

The harmless little flying lizards, belonging to the genus Draco, abounding in the East Indian archipelago, which have many of their posterior ribs prolonged into an expansion of the integument, unconnected with the limbs, and have a limited and parachute-like flight, need only the element of size, to render them also sufficiently to be dreaded, and capable of rivalling the Pterodactyls in suggesting the general idea of the same monster.

It is, however, when we pass to some of the other groups, that we find ourselves in the presence of forms so vast and terrible, as to more than realise the most exaggerated impression of reptilian power and ferocity which the florid imagination of man can conceive.

We have long been acquainted with numerous gigantic terrestrial Saurians, ranging throughout the whole of the Mesozoic formations, such as Iguanodon (characteristic of the Wealden), Megalosaurus (Great Saurian), and Hylæosaurus (Forest Saurian), huge bulky creatures, the last of which, at least, was protected by dermal armour partially produced into prodigious spines; as well as with remarkable forms essentially marine, such as Icthyosaurus (Fish-like Saurian), Plesiosaurus, &c., adapted to an oceanic existence and propelling themselves by means of paddles. The latter, it may be remarked, was furnished with a long slender swan-like neck, which, carried above the surface of the water, would present the appearance of the anterior portion of a serpent.

To the related land forms the collective term Dinosauria (from δεινός “terrible”) has been applied, in signification of the power which their structure and magnitude imply that they possessed; and to the others that of Enaliosauria, as expressive of their adaptation to a maritime existence. Yet, wonderful to relate, those creatures which have for so many years commanded our admiration fade into insignificance in comparison with others which are proved, by the discoveries of the last few years, to have existed abundantly upon, or near to, the American continent during the Cretaceous and Jurassic periods, by which they are surpassed, in point of magnitude, as much as they themselves exceed the mass of the larger Vertebrata.

Take, for example, those referred to by Professor Marsh in the course of an address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in 1877, in the following terms: – “The reptiles most characteristic of our American cretaceous strata are the Mososauria, a group with very few representatives in other parts of the world. In our cretaceous seas they rule supreme, as their numbers, size, and carnivorous habits enabled them to easily vanquish all rivals. Some were at least sixty feet in length, and the smallest ten or twelve. In the inland cretaceous sea from which the Rocky Mountains were beginning to emerge, these ancient ‘sea-serpents’ abounded, and many were entombed in its muddy bottom; on one occasion, as I rode through a valley washed out of this old ocean-bed, I saw no less than seven different skeletons of these monsters in sight at once. The Mososauria were essentially swimming lizards with four well-developed paddles, and they had little affinity with modern serpents, to which they have been compared.”

Or, again, notice the specimens of the genus Cidastes, which are also described as veritable sea-serpents of those ancient seas, whose huge bones and almost incredible number of vertebræ show them to have attained a length of nearly two hundred feet. The remains of no less than ten of these monsters were seen by Professor Mudge, while riding through the Mauvaise Terres of Colorado, strewn upon the plains, their whitened bones bleached in the suns of centuries, and their gaping jaws armed with ferocious teeth, telling a wonderful tale of their power when alive.

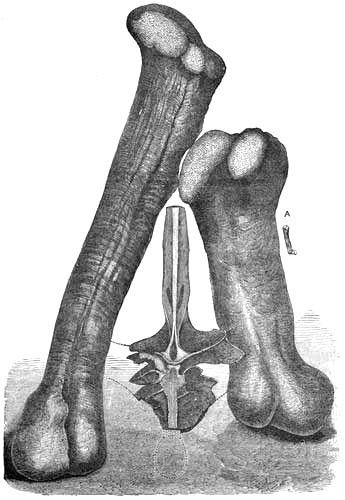

The same deposits have been equally fertile in the remains of terrestrial animals of gigantic size. The Titanosaurus montanus, believed to have been herbivorous, is estimated to have reached fifty or sixty feet in length; while other Dinosaurians of still more gigantic proportions, from the Jurassic beds of the Rocky Mountains, have been described by Professor Marsh. Among the discovered remains of Atlantosaurus immanis is a femur over six feet in length, and it is estimated from a comparison of this specimen with the same bone in living reptiles that this species, if similar in proportions to the crocodile, would have been over one hundred feet in length.

But even yet the limit has not been reached, and we hear of the discovery of the remains of another form, of such Titanic proportions as to possess a thigh-bone over twelve feet in length.

Fig. 5. – Monster bones of extinct gigantic Sauriansfrom Colorado, showing relative proportionsto corresponding bone in the Crocodile (A).

(From the “Scientific American.”)

From these considerations it is evident that, on account of the dimensions usually assigned to them, no discredit can be attached to the existence of the fabulous monsters of which we shall speak hereafter; for these, in the various myths, rarely or never equal in size creatures which science shows to have existed in a comparatively recent geological age, while the quaintest conception could hardly equal the reality of yet another of the American Dinosaurs, Stegosaurus, which appears to have been herbivorous, and more or less aquatic in habit, adapted for sitting upon its hinder extremities, and protected by bony plate and numerous spines. It reached thirty feet in length. Professor Marsh considers that this, when alive, must have presented the strangest appearance of all the Dinosaurs yet discovered.

The affinities of birds and reptiles have been so clearly demonstrated of late years, as to cause Professor Huxley and many other comparative anatomists to bridge over the wide gap which was formerly considered to divide the two classes, and to bracket them together in one class, to which the name Sauropsidæ has been given.35