полная версия

полная версияPincher Martin, O.D.: A Story of the Inner Life of the Royal Navy

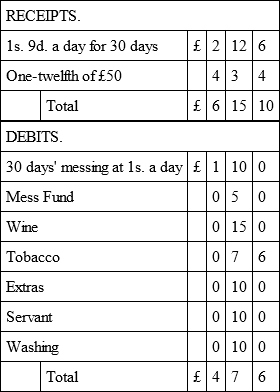

'Snotties' over eighteen were allowed to expend fifteen shillings a month on wine, and those under this age five shillings less; but nobody under twenty was permitted to touch spirits. The mess fund – for newspapers, breakages, washing, and other small incidental expenses – came to a nominal five shillings a month, but generally exceeded it; servant's wages were ten shillings; personal washing, say, ten shillings; and tobacco – if the officer was over eighteen, and allowed to smoke – about seven shillings and sixpence or half-a-sovereign. The monthly balance-sheet, omitting all extravagances, therefore, worked out somewhat as follows:

This, omitting the 'extra-extra,' left a nominal credit balance of two pounds eight shillings and fourpence wherewith to last out the month. Only one or two of the 'snotties' received anything extra in the way of allowances from their people, though their outfitters' bills for all necessaries in the way of clothing were usually met by their parents. But even this did not improve matters to any great extent, and not one of the young officers was ever known to have much in the way of money unless parents or relations behaved handsomely on birthdays or at Christmas. Even then the gift dwindled rapidly, for if one of them did receive a windfall of an odd pound or two, he took care that his messmates shared his good fortune. The clothes they had, too, were in a perpetual state of being lost; and if one of them was asked out to dine in another ship, everybody contributed something towards his attire. One provided a shirt, and others handkerchief, collar, tie, and evening shoes; but in spite of it all they somehow always managed to look smart and well-dressed.

This state of chronic hardupness is hereditary in midshipmen. History relates that a youth once came home from China, and landed at Portsmouth with no soles to his boots, a hole in the crown of his straw hat – it had been eaten by cockroaches – the seat of his trousers darned by himself with sail-makers' twine, and no tails to any of his shirts. With the ready resource of the sailor, he had removed these for use as pocket-handkerchiefs.

The Royal Navy is essentially a poor man's service, and comparatively few of its officers have anything considerable in the way of means over and beyond their pay. It is sometimes difficult to keep out of debt, for they are expected to go everywhere and do everything, while uniform is expensive, and the cost of living is always increasing. It seems to be part of a midshipman's job to be poor, and one would as soon expect to find a dustman with a gold-mounted shaving-set as a 'snotty' with more than half-a-crown in his pocket on the 28th of the month.

The 'snotties' of the Belligerent were no exception to the general rule. They were quite irrepressible, and were as happy and cheerful as they could be, though sometimes they did complain bitterly that they were half-starved. On occasions, to the accompaniment of spoons beaten on the table, they chanted a mournful dirge anent the iniquities of the messman. It was long and rather ribald, but the last two lines of the chorus ran:

We're starving! we're starving!And the messman's name is Mr Tubbs!They weren't really so famished as they pretended to be, but Tubbs certainly was an old rogue. One celebrated morning, when the senior sub-lieutenant was absent, he peered through the pantry hatch at breakfast-time.

'Now, gennelmen,' he said, 'wot we 'ave for breakfast is 'ot sardines an' 'am. Sardines is a bit orf, the 'am is tainted, an' fruit is extra. Wot'll you 'ave?'

The ship was half-way across the Bay of Biscay at the time, and had been at sea for several days, so perhaps there was some slight excuse for the inadequacies of the morning meal. But Tubbs had tried this game before; and, headed by Roger More, the junior sub-lieutenant, the members of the mess rose en bloc and hastily armed themselves with dirks.

The messman, scenting trouble, promptly fled from the pantry with his satellites after him, while the hungry officers rushed in, broke open various cupboards, and helped themselves liberally to Tubbs's private store of tinned kippers and haddock. He complained bitterly, but got no redress.

Another time the members of the mess were sitting round the table waiting impatiently for lunch. Noon was the proper time for the meal; but at twelve-ten nothing had appeared on the table except the vegetables. The hungry officers commenced to bang on the table with eating implements, and started the inevitable dirge, and in the middle of it Tubbs's face appeared framed in the pantry hatch.

'I'm sorry, gennelmen,' he said when he could make himself heard in the uproar. 'The boy's fallen down the 'atch with the joint, an' it ain't fit be to seen. I've some werry nice corned beef' —

A chorus of groans drowned his utterance. 'Let's see the joint,' some one demanded.

'It's bin thrown overboard, sir,' the messman explained glibly, disappearing from view.

Several of the junior midshipmen and the assistant-clerk were despatched to visit the scene of the alleged accident, and to report on what traces they found. There were none. There never had been any joint.

'Tubbs!' they yelled in unison when the spies came back.

The messman's head appeared, and the minute it bobbed up into sight it was greeted with a volley of vegetables. On the whole the shooting was good, and Tubbs made an excellent Aunt Sally. Potatoes baked in their jackets spattered and burst all round the pantry hatch like a rafale of shrapnel-shell, while some, passing through, exploded on impact with the messman's head. The pièce de résistance was a cauliflower. It struck the ledge and detonated like a high-explosive projectile, and the messman received its disintegrated stickiness full in the face. He slammed the hatch up with a bang, and rushed into the mess with his face, beard, and hair dripping with vegetable products; while the culprits, wildly excited, shrieked with laughter. The bombardment would have continued, but the available ammunition was expended.

Tubbs was furious. 'I'll 'ave the law on yer!' he shouted wildly, waving his fists. 'I'll report yer to the commander, and 'ave yer court-martialled, see if I don't! It's disgraceful, that's wot it is, an' wot the navy's comin' to I don't know! Calls yerselves gennelmen, do yer?'

He went on for quite a long time; but nothing further ever came of it. He knew well enough that he had brought it on himself, and thereafter he became rather more particular over the matter of providing meals.

It must not be imagined that the inhabitants of the Belligerent's gunroom always behaved like this. On the contrary, they were an unusually well-conducted mess, and they broke out only when they were really exasperated, and their feelings got the better of them.

The sub, assisted by the senior 'snotties,' had drilled the Crabs into a high state of discipline and efficiency. He believed in using the terror of the stick as a deterrent rather than in employing the weapon itself, and as a consequence the junior midshipmen were never beaten really hard unless they misbehaved themselves. But as Cook himself once remarked, 'You can bet your bottom dollar that for every sin they've been bowled out committing, there are fully fifty more that we haven't discovered;' and there was some truth in the remark.

One of the methods of smartening up the Crabs was an evolution known as 'fork in the beam.' This was a time-honoured custom which must have started in the days of wooden sailing-ships, since it is hardly possible to stick an ordinary table-fork into the steel beams of a modern vessel. It generally took place during dinner, when the younger members of the mess had been making too much noise.

The sub, standing up at his place at the end of the table, would insinuate a fork into the electric wires overhead, and at this signal all the junior midshipmen and the assistant-clerk had to leave the mess, scamper twice round the boat-deck, and return in the shortest possible time. In the old-time evolution itself the 'snotties' used to run up the rigging and over the masthead, but Cook substituted the race round the boat-deck as being less dangerous. The last officer back had to repeat the performance; and, as the loser generally found that somebody had drunk his beer during his absence, there was always great competition to be away first. It usually started by a seething mass of seven Crabs being stuck in the doorway. After much struggling and pushing, they would eventually fall through into the flat amidst shrill yelps from the young gentlemen who happened to be underneath, and remarks of 'Get off my face!' 'Ow! let go my leg, you beast!' Then, sorting themselves out one by one, they would dart off, to return a few minutes later flushed and breathless after their exercise.

They were also organised as what were known as the 'dogs of war,' with the idea, as the sub explained, of instilling them with martial ardour and making them fierce. On the order, 'Dogs of war out – so and so!' they were expected to growl viciously, hurl themselves upon the person named, and cast him forth from the mess. Sometimes the assistant-clerk was the victim, sometimes one of the 'snotties' themselves; but, to make things really exciting, the 'dogs' were occasionally divided into two sides, Red and Blue, and each party endeavoured to expel the other. It always meant a frantic struggle, for the victim or victims resisted violently. They were none too gentle either, for clothes were torn, shirts and collars were destroyed, and bruises were by no means infrequent. Sometimes people's noses bled, and the fight waxed really furious; but cases of lost temper were comparatively rare, and the 'dogs' usually enjoyed the fun as much as any one else. Their parents, had they been present during the strife, might not have been quite so amused. They paid for the clothes.

The star turn, however, was the Crabs' corps de ballet, and it occasionally disported itself on guest nights for the amusement and edification of any strangers who happened to be present. Trevelyan, the senior midshipman, was the stage manager, and what the ballet lost through lack of histrionic power on the part of the performers it more than made up for by its originality. Their attire was sketchy, to say the least of it. It consisted mainly of bath-towels, sea-boots, and straw hats; and the songs and dances, to the strains of the elderly, asthmatic piano, and bagpipes played by a Scots midshipman, MacDonald, usually brought down the house. If by any chance the performance fell at all flat through a lack of energy on the part of the performers, they were promptly converted into 'dogs of war,' with the inevitable result. So, taking it all round, the occupants of 'the 'Orrible Den' managed to amuse themselves.

But because they sometimes became riotous and irresponsible in the gunroom, it must not be imagined that the younger officers were not learning their trade. Far from it; they worked really very hard, on deck, in the engine-room, and in pursuit of the wily and elusive x. Their day started at six-fifteen, and between six-forty and seven o'clock they were either away boat-pulling or at physical drill or rifle exercise. After this came baths, and from seven-forty-five till eight instruction in signals. Breakfast was at eight; and from nine till eleven-forty-five, and again in the afternoon from one-fifteen to three-fifteen, they were at instruction in seamanship, gunnery, torpedo, navigation, or engineering. Voluntary instruction in theoretical subjects took place for one and a half hours on three evenings of the week, and those more backward youths who did not volunteer were compelled to attend. Two nights a week, from eight-thirty till nine, there were signal exercises with the Morse lamp, and these had to be attended by all the midshipmen until they attained a certain standard of proficiency.

In addition to this, they had their regular watches to keep – day and night at sea, and from eight-thirty A.M. till eight P.M. in harbour; while no boat ever left the ship under steam or sail without a 'snotty' in charge. Their days, therefore, were pretty busy.

They generally managed to get ashore between three-thirty and seven P.M. about two days out of every four, and on Saturdays and Sundays from one-thirty; but no late leave was granted save in very exceptional circumstances. They amused themselves with hockey and football in the winter, and golf, tennis, and cricket in the summer; and at places where games could not be played, solaced their feelings by borrowing one of the ship's boats on Sunday afternoons, stocking her with great hampers containing provender of all kinds, and then sailing off for a picnic. There is an irresistible fascination in cooking sausages and boiling a kettle over a home-made fire on some unfrequented island or beach which appeals to the most sober-minded of us.

Your modern midshipmen are no longer the rosy-cheeked, blue-eyed little cherubs of fiction. Many of them are over six feet, some of them shave, and nobody but their aunts and female cousins refer to them as 'middies.' To call them by that diminutive term to their faces would make them squirm. They refer to themselves as 'snotties,' and 'snotties' they will remain till the end of the chapter. The name, rather inelegant perhaps, owes its origin to the three buttons on the cuffs of their full-dress short jackets, which ribald people used to say were first placed there to prevent their sleeves being put to the use generally delegated to pocket-handkerchiefs. Any schoolboy will tell you what a 'snot rag' is; but I have never yet heard of a modern midshipman being without this rather important article of dress.

'Snotties' are a strange mixture. They possess all the love of fun and excitement of schoolboys, but once on duty are very much officers. They have to undertake responsibility very young, and at an age when their shore-going brothers are still at public schools their careers in the service have started.

Seamanship is not an exact science; it is an art. It comprises, amongst other things, experience, sound judgment, good nerve, a vast deal of common-sense, and a happy knack of knowing when risks are justifiable and when they are not. It is a subject which cannot be taught by rule of thumb after the first groundwork of elementary knowledge has been assimilated, and circumstances alter cases so greatly that no preceptor on this earth could lay down hard-and-fast rules for each of the thousand-and-fifty contingencies which may arise at sea, and which may one day have to be guarded against or overcome. The sea, moreover, is a fickle mistress. The navy is always on active service, in peace or in war, for its men and its ships are for ever pitting their skill and strength against the might of the most merciless of enemies – the elements. From the very moment that midshipmen join their first ship they are expected to take part in the great game, and sometimes it is a game of life and death. They start off by being placed in charge of boats in all weathers. They may be steamboats, or boats under sail; but whichever they are, the 'snotties' are learning their trade. If they do something foolish they may cause great damage to valuable property, may even be the means of men losing their lives; but they generally succeed in getting out of scrapes and difficulties with some credit to themselves.

The strenuous training and habit of early responsibility may convert them into men before their time; but they still manage to retain their boyish instincts, and when they are off duty these generally appear uppermost. At times they are noisy, riotous, and altogether irrepressible; but when it comes to work they are very much all there.

II

'Ain't got a fill o' bacca abart yer, 'ave yer?' asked Joshua Billings, A.B., producing an abbreviated, blackened, and very foul clay pipe from the lining of his cap and gazing at it pensively. It was twelve-forty-five P.M., the middle of the dinner-hour, and Joshua, having just assimilated his tot of navy rum, was at peace with himself and the world in general.

'Sorry,' Martin answered, 'I ain't got nothin' but fags.'

'Fags!' the able seaman growled. 'Why you young blokes smokes nothin' but them things I dunno. They tastes like smokin' 'ay. W'en I fu'st jined I takes up me pun' o' bacca reg'lar, an' I done it ever since. It's got some taste abart it. Fags! S'welp me, I dunno wot th' blessed navy's comin' to!'

Martin looked rather sheepish.

Billings grinned. 'Seein' as 'ow you ain't got no bacca, then I s'pose I've got ter use me own,' he went on, producing a well-filled pouch from the waistband of his trousers, and proceeding to ram some coarse, dark tobacco into his pipe. 'I never believes in usin' me own s'long as I kin git a fill orf another bloke. Got a match?'

The ordinary seaman handed a box across, and his companion lit up.

'Comin' ashore along o' me this arternoon?' Joshua asked, puffing out a cloud of smoke with a satisfied grunt.

Martin thought for a moment. For an ordinary seaman to be asked to go ashore with a man of Billings's age was undoubtedly a great honour; but, at the same time, he was rather doubtful as to what might happen. Joshua, on his own statement, had an unquenchable thirst for malt liquor, and always felt 'dizzy like' outside public-houses, and Martin had no wish to join him in a carouse, with the prospect of ending the afternoon under the supervision of the local constabulary.

'Goin' on th' razzle?'16 he asked cautiously.

Billings laughed. 'Razzle!' he exclaimed. 'No, I ain't on that lay. I'll 'ave jist one pint w'en I gits ashore, but no more'n that. The fac' o' the matter is, Pincher, I'm in love.' He paused to give his words time to sink in.

'In love!' Martin echoed with some astonishment.

The A.B. nodded gravely. 'Yus,' he said; 'an' I want some one to come along an' 'old me 'and like, some bloke wot looks young an' innercent like you.' He endeavoured to look young and innocent himself, gazed heavenwards with a rapt expression on his homely face, contorted his mouth into what he considered was a sweet smile, and sighed deeply. 'I tell yer,' he added, resuming his normal appearance and winking solemnly, 'she's a bit o' orl right, an' I reckons she's took a fancy ter me. Leastways she 'inted that she'd come to th' pictures along o' me ter-night if I arsked 'er polite like, an' 'ave a bit o' somethin' t' eat arterwards.'

'You in love!' Martin gasped again, for to him it seemed impossible that any woman could succumb to the doubtful charms of the hoary-headed old reprobate. 'Garn! you're 'avin' me on.'

Joshua seemed rather annoyed. 'Oh no, I ain't,' he retorted testily. 'An' if yer gits talkin' like that me an' you'll part brassrags.17 She ain't th' sort o' 'ooman ter take a fancy to a young bloke. Wot she wants is some one ter look arter 'er an' 'er property. A bloke wi' hexperience, the same as me.'

'Property! 'Oo is she, then?'

'You mustn't go tellin' the other blokes if I tells yer,' Billings said, sinking his voice to a whisper. 'Promise yer won't.'

'Orl right, I won't.'

'She's a widder 'ooman wot keeps a sweet an' bacca shop, an' sells noospapers. She's makin' a good thing out o' it, too – clearin' 'bout three pun' a week, she sez she is; an' as my time's comin' along for pension, it's abart time I started lookin' round fur somethin' ter do w'en I leaves the navy. She ain't no young an' flighty female neither, I gives yer my word. Got a growed-up darter, she 'as, seventeen year old, an' I reckons it's abart time th' poor gal 'ad another father ter look arter 'er. You see,' he added, 'if I gits married to th' old un orl the blokes wot knows me'll come to the shop to buy their fags an' noospapers, so it ain't as if I was bringin' nothin' to th' business. I'm a bloke wi' inflooence, I am. 'Er larst 'usband drove a cab, 'e did, an' I reckons she's betterin' 'erself by marryin' a bloke wot's bin in the navy.'

'An' wot's this 'ere gal o' 'ers like?' Pincher wanted to know. 'Is she a cosy bit o' fluff too?'

'Cosy bit o' fluff!' exclaimed Joshua with some warmth. 'Wot d'yer mean, yer lop-eared tickler?18 She ain't fur the likes o' you, any'ow.'

'Oh, ain't she?' Martin retorted. 'Well, I ain't comin' ashore along o' yer, then!'

''Ere, don't git yer dander up,' Billings interrupted, changing his tone; 'I didn't mean nothin'.' He was really very anxious that Martin should accompany him, for he had a vague idea in his head that the presence of a younger man would lend tone to the proceedings, and to him a certain air of respectability.

'Don't act so snappy, then,' the ordinary seaman returned. 'I'm as good as any other bloke.' He remembered that he was a member of the ship's football team, and this alone made him a person of some importance.

'Well, if yer really wants ter know, th' gal's name's Hemmeline, an' she's walkin' out wi' a ship's stooard's assistant bloke from the flagship.'

'Ship's stooards ain't no class!' Pincher snorted, expanding his chest to its full capacity. 'They ain't fightin' blokes same as me an' you.'

'No, they ain't,' Billings agreed, puffing slowly at his pipe. 'They ain't got no prospex neither. Look 'ere, Pincher,' he added, 'she's only bin along wi' 'im fur a week, an' if yer fancies 'er, my inflooence wi' 'er ma' —

'Meanin' that I can take 'er out?' Martin queried.

Joshua nodded. 'That's the wheeze,' he said, expectorating with deadly precision into a spit-kid at least eight feet distant.

'But wot's she look like?' Pincher demanded with caution. Up to the present he had felt rather frightened of women; but to have a proper sweetheart in tow was one of the things he really longed for. It would complete his new-found manhood. But he had his own ideas of feminine beauty, and, whatever happened, the young lady must be pretty.

Billings grinned. 'She's orl right,' he explained. 'She ain't 'xactly tall, nor yet 'xactly short. Sort o' betwixt an' between like. She ain't too fat, nor yet too lean; she's sort o' plump. Yaller 'air, she 'as, an' blue eyes, an' plays th' pianner wonderful, 'er ma sez.'

This rather vague description of the fair Emmeline's charms seemed quite enough for Martin. 'She sounds orl right,' he said. 'I think I'll come along o' you.'

Joshua seemed rather pleased. 'That's th' ticket,' he said. 'We goes ashore in th' four o'clock boat, mind. Say, chum,' he added in a hoarse whisper, 'you ain't got 'arf-a-dollar to lend us, 'ave yer?'

Martin looked rather dubious. ''Arf-a-dollar!' he sniffed.

'Yus,' urged the A.B. 'I've only got three bob o' me own, an' I've got ter take th' lady to th' pictures, an' give 'er a bit o' supper arterwards. The show's orf 'less I kin raise some splosh some'ow. W'y don't yer come along too, an' bring the gal?'

'Carn't do it,' the ordinary seaman murmured. 'Me leaf's up at seven, an' I don't want to go gittin' in th' rattle fur breakin' it. But I'll lend yer a couple o' bob if yer promises faithful to pay me back. I'll give it yer afore we goes ashore.'

'Good on yer, chum,' said Billings effusively. 'I reckons yer knows 'ow to be'ave to blokes wot takes a hinterest in yer. You take my tip, though,' he added, wagging an admonitory forefinger. 'Don't yer go lendin' money to any other blokes wot ain't fit to be trusted.'

'I'll watch it,' Martin laughed.

And so it was arranged, and this was how Pincher Martin embarked on his first love affair.

CHAPTER VII

AN AFFAIR OF THE HEART

I

Miss Emmeline Figgins was a well-built, capable-looking young lady of seventeen. She wore her hair neatly coiled in a golden aureole on the top of her head. Her blue eyes were attractive and full of mirth, her mouth was well-shaped, and she possessed a pair of very red lips and twin rows of even white teeth. She seemed literally bursting with health, and her rosy, slightly sunburnt cheeks somehow reminded Pincher of the girls at home in his own village. She was dressed in a white blouse and plain dark-blue skirt, and a small gold locket hung round her neck.

The first time Martin saw her standing behind the counter in the little sweet and tobacco shop he thought her quite adorable. He experienced a vague feeling of jealousy when he saw the locket, though, for he thought it probable that it contained the photograph of the ship's steward's assistant from the flagship.