полная версия

полная версияThe Expositor's Bible: The First Book of Kings

CHAPTER XLVIII.

CONCLUSION

It will have been seen that there are two main heroes of the First Book of Kings – Solomon and Elijah. How vast is the gulf which separates those two ideals! In Solomon we see man in all the adventitious splendour which he can derive from magnificent surroundings and from exaltation to a dizzy height above his fellows. Everything that the earth can give him he possesses from earliest youth, yet all turns to dust and ashes under his touch. Wealth, rank, power, splendour cannot ever, or under any circumstances, satisfy the soul. The soul can only be sustained by heavenly food, by the manna which God sends it from heaven in the wilderness. Its divineness can only be maintained by feeding on the Divine. If we think of Solomon, even in his most dazzling hour, we see no element of happiness or of reality in his lonely splendour or loveless home. It is nothing but a miserable pageant. The Book of Ecclesiastes, though written centuries after he had passed away, yet shows sufficiently, as the Eastern legends also show, that mankind was not misled by the glamour which surrounded him into the supposition that he was to be envied. It was felt, whether he uttered it or not, that "Vanity of vanities, vanity of vanities, all is vanity," is the real echo of his weariness. In the famous fiction the Khaliph sees him with the other giant shades on his golden throne at the banquet; but each and all have on their faces an expression of solemn agony, and under the folds of their purple a little flame is ever burning at their hearts.

How different is the rough Prophet of Gilead, the ascetic, in his sheepskin mantle and leathern girdle, who can live for months on a little water and meal baked with oil!788 In him we see the grandeur of manhood reduced to its simplest elements; we see the dignity of man as simply man towering over all the adventitious circumstance of royalty. One who, like Elijah, has no earthly desires, has no real fears. If he flies from Jezebel to save his life, it is only because he is not justified in flinging it away; otherwise he is as dauntless before the vultus instantis tyranni as before the civium ardor prava jubentium. Hence, Elijah in his absolute poverty, in his despised isolation – Elijah, hunted and persecuted, and living in dens and caves of the earth – is immeasurably greater than Solomon, because he is the messenger of the living God before whom he stands. And his work is immeasurably more permanent and more valuable for humanity than that of all the kings and great men among whom he moved. He believed in God, he fought for righteousness, and therefore he left behind him an unperishable memorial, showing that he who would live for eternity rather than for time is he who best achieves the high ends of his destiny. He may err as Elijah erred, but with the blessing of the Lord he shall not miscarry. Though he go forth weeping, he shall come again with joy, bringing his sheaves with him. Solomon, after his death, almost vanished from the history of Israel into the legends of Arabia. In the New Testament he is but barely mentioned. But Elijah still lives in, and haunts, the memory of his nation. A chair is placed for his invisible presence at every circumcision. A cup is set aside for him at sacred banquets, and all dubious questions are postponed for solution "until the day when Elijah comes." He shone with Moses on the Mount of Transfiguration; and St. James, the Lord's brother, appeals to him as the most striking example of the power of that prayer which

"Moves the arm of Him who moves the world."

NOTE ON THE CHRONOLOGY OF THE FIRST BOOK OF KINGS

I have not thought it worth while to trouble the reader with conjectures or corrections of the text, intended to remove the numerous and obvious discrepancies which the redactor of the Book of Kings leaves uncorrected in his references to the synchronism of the reigns.789 Many of them are removed or modified when we bear in mind that, e. g., Nadab and Elah and Ahaziah are described as reigning "two years" each (xv. 25, xvi. 8, xxii. 51), whereas the reign of each may not have exceeded a year, or even a few months, if these months came at the end of one year and the beginning of another. Periods of anarchic interregnum, or of association of a son with his father on the throne, may account for other confusions and contradictions; but they are purely conjectural, and in some cases far from probable. Jerome, as is well known, gave up all attempts to harmonise the chronologic data as a hopeless problem. "Relege," he says, "omnes et veteris et novi Testamenti libros, et tantam annorum reperies dissonantiam ut hujuscemodi hærere quæstionibus non tam studiosi quam otiosi hominis esse videatur."

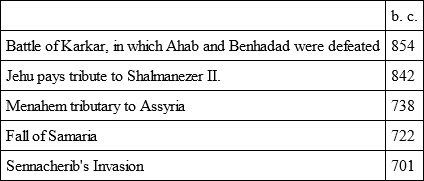

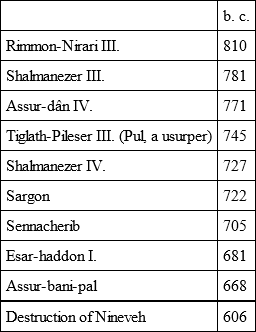

The Assyrians were, for the most part (though, as Schrader shows, not always), as scrupulously exact in their chronological details as the Jews were careless in theirs. The cuneiform inscriptions give us the following data, which may be regarded as points de repère, and which are not reconcilable with the received dates: —

These dates do not accord with those which we should derive from the Book of Kings in the ordinary system of chronology, which seem to fix the Fall of Samaria in 737.

The dates of the later Kings of Assyria seem to be as follows: —

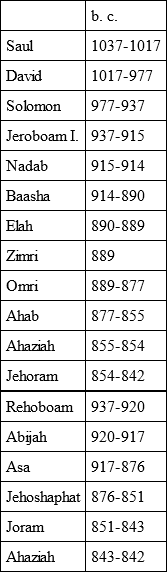

Adding up the separate data of this book for the kings of Israel we have from Jeroboam to the death of Joram ninety-eight years seven days; and for the same period of the kings of Judah from Rehoboam to Ahaziah we have ninety-five years. Supposing that some such errors as we have indicated have crept into the computation, the dates of the reigns may be, as reckoned by Kittel: —

From Phœnician inscriptions (recorded in the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum) little of historical importance has hitherto been reaped.

In the Egyptian monuments there is nothing which illustrates the period of the Kings except the inscription of Sheshonk recording his invasion in the days of Rehoboam, of which I have given some account (p. 315).

The Assyrian inscriptions, to which allusion is made in their place, are of extreme importance and interest, and from the lists of kings we have good details of chronology. The best book on their bearing upon Hebrew history is that of Schrader, Die Keilinschriften und d. Alte Testament, 1883.

On the datum of four hundred and eighty years from the Exodus to the building of the Temple, I have already touched. It does not agree with Acts xiii. 20, nor with the Book of Judges. The LXX. reads "four hundred and forty." It is almost certainly a late and erroneous chronological gloss derived in very simple fashion, thus: – The wanderings forty years, Joshua forty years, Othniel forty years, Ehud eighty years, Jabin twenty years, Barak forty years, Gideon forty years, the Philistines forty years, Samson twenty years, Samuel forty years, Saul forty years, David forty years = four hundred and eighty, or twelve generations of forty years.

But the same result was arrived at with equal empiricism by omitting the episodes of heathen dominations (Jabin and the Philistines), and only adding up the years assigned to the Judges, and the four years of Solomon's reign before he began to build the Temple, thus: – Othniel forty years, Ehud eighty years, Barak forty years, Gideon forty years, Tola twenty-three years, Jair twenty-two years, Jephthah six years, Ibzan seven years, Elom ten years, Abdon eight years, Samson twenty years = two hundred and ninety-six.

Eli forty years, Samuel twenty years (1 Sam. vii. 15), David forty years, Solomon four = one hundred and four. Add to the four hundred the two generations of the wanderings and Joshua, and we again have four hundred and eighty; but quite as arbitrarily, for the period of Saul is omitted.790

The problems of early Hebrew chronology cannot yet be regarded as even approximately solved.

1

"Scriptura est sensus Scripturæ." – St. Augustine.

2

For a decisive proof of these statements I refer to my Bampton Lectures on the History of Interpretation (Macmillan, 1890).

3

Bacon.

4

How closely these documents are transcribed is shown by the recurrence of "unto this day," though the phrase had long ceased to be true when the book appeared.

5

It is inferred from 1 Kings viii. 12, 13, which have a poetic tinge, and to which the LXX. add "Behold they are written in the Book of the Song," that in this section the "Book of Jashar" has been utilised, and that the reading הישר has been confused with השיר (Driver, p. 182).

6

2 Chron. xx. 34, R.V., "The history of Jehu, the son of Hanani, which is inserted in the Book of the Kings of Israel" (not "who is mentioned," A.V., which, however, gives in the margin the literal meaning "was made to ascend").

7

Movers, Krit. Untersuch., p. 185 (Bonn, 1836). The use of older documents explains the phrase "till this day," and the passages which speak of the Temple as still standing (1 Kings viii. 8, ix. 21, xii. 19; 2 Kings x. 27, xiii. 23). Sometimes the traces of earlier and later date are curiously juxtaposed, as in 2 Kings xvii. 18, 21 and 19, 20.

8

Difference of sources is marked by the different designations of the months, which are called sometimes by their numbers, as in the Priestly Codex (1 Kings xii. 32, 33), sometimes by the old Hebrew names Zif ("blossom," April, May, 1 Kings vi. 1), Ethanim ("fruit," Sept., Oct., 1 Kings viii. 2), and Bul ("rain," 1 Kings vi. 38).

9

מִז־הַנָּהָר (compare עֲבַר־נַהֲרָה). Lit., "Beyond the river," i. e., from the Persian standpoint. It becomes a fixed geographical phrase. Traces of the editor's hand occur in 1 Kings xiii. 32 ("the cities of Samaria"); 2 Kings xiii. 23 ("as yet").

10

Comp. 2 Kings viii. 25 with ix. 29.

11

See 2 Kings xv. 30 and 33, viii. 25 and ix. 29.

12

As, perhaps, the clause "In the thirty and first year of Asa king of Judah" in 1 Kings xvi. 23; and the much more serious "in the 480th year after the children of Israel were come out of the land of Egypt," which are omitted by Origen (comm. in Johannem, ii. 20), and create many difficulties. The only narratives which critics have suggested as possible interpolations, from the occurrence of unusual grammatical forms, are 2 Kings viii. 1-6 and iv. 1-37 (in the story of Elisha); but these forms are perhaps northern provincialisms.

13

Speaker's Commentary, ii. 475. Instances will be found in 1 Kings xiv. 21, xvi. 23, 29; 2 Kings iii. 1, xiii. 10, xv. 1, 30, 33, xiv. 23, xvi. 2, xvii. 1, xviii. 2.

14

Stade, p. 79; Kalisch, Exodus, p. 495.

15

See Keil, pp. 9, 10.

16

R. F. Horton, Inspiration, p. 843.

17

He was not the author of the Book of Samuel, for the standpoint and style are quite different. In the First and Second Books of Samuel the high places are never condemned, as they are incessantly in Kings (1 Kings iii. 2, xiii. 32, xiv. 23, xv. 14, xxii. 43, etc.).

18

Baba Bathra, 15 a.

19

Seder Olam Rabba, 20.

20

Even then he would have been ninety years old.

21

There are, however, some differences between 2 Kings xxv. and Jer. lii. (see Keil, p. 12), though the manner is the same, Carpzov, Introd., i. 262-64 (Hävernick, Einleit., ii. 171). Jer. li. (verse 64) ends with "Thus far are the words of Jeremiah," excluding him from the authorship of chap. lii. (Driver, Introd., p. 109). The last chapter of Jeremiah was perhaps added to his volume by a later editor.

22

"The Old Testament does not furnish a history of Israel, though it supplies the materials from which such a history can be constructed. For example, the narrative of Kings gives but the merest outline of the events that preceded the fall of Samaria. To understand the inner history of the time we must fill up this outline with the aid of the prophets Amos and Hoshea." – Robertson Smith's Preface to translation of Wellhausen, p. vii.

23

"In der Chronik," on the other hand, "ist es der Pentateuch, d.h. vor Allem der Priestercodex, nach dessen Muster die Geschichte des alten Israels dargestellt wird" (Wellhausen, Prolegom., p. 309). It has been said that the Book of Kings reflects the political and prophetic view, and the Book of Chronicles the priestly view of Jewish history. It is about the Pentateuch, its date and composition, that the battle of the Higher Criticism chiefly rages. With that we are but indirectly concerned in considering the Book of Kings; but it is noticeable that the ablest and most competent defender of the more conservative criticism, Professor James Robertson, D.D., both in his contribution to Book by Book and in his Early Religion of Israel, makes large concessions. Thus he says, "It is particularly to be noticed that in the Book of the Pentateuch itself the Mosaic origin is not claimed" (Book by Book, p. 5). "The anonymous character of all the historical writings of the Old Testament would lead us to conclude that the ancient Hebrews had not the idea of literary property which we attach to authorship" (p. 8). "It is long since the composite character of the Pentateuch was observed" (p. 9). "There may remain doubts as to when the various parts of the Pentateuch were actually written down; it may be admitted that the later writers wrote in the light of the events and circumstances of their own times" (p. 16).

24

Driver, p. 189. Comp. Professor Robertson Smith: "The most notable feature in the extant redactions of the book is the strong interest shown in the Deuteronomic law of Moses, and especially in the centralisation of worship in the Temple on Zion, as pre-supposed in Deuteronomy and enforced by Josiah. This interest did not exist in ancient Israel, and is quite foreign to the older memories incorporated in the book."

25

Driver, p. 192.

26

Delitzsch, Genesis, 6th ed., p. 567.

27

Geschichte des Volkes Israel, i. 73.

28

Even the First Book of Maccabees begins with καὶ ἐγένετο.

29

Stade, pp. 32 ff. Thus, in 1 Kings viii. 14-53, verses 12, 13 are in the Septuagint placed after verse 53, are incomplete in the Hebrew text, and have a remarkable reading in the Targum. Professor Robertson Smith infers that a Deuteronomic insertion has misplaced them in one text, and mutilated them in another. The order of the LXX. differs in 1 Kings iv. 19-27; and it omits 1 Kings vi. 11-14; ix. 15-26. It transposes the story of Naboth, and omits the story of Ahijah and Abijah, which is added from Aquila's version to the Alexandrian MS. See Wellhausen-Bleek, Einleitung, §§ 114, 134.

30

See Appendix on the Chronology.

31

See Wellhausen, Prolegomena, pp. 285-87; Robertson Smith, Journ. of Philology, x. 209-13.

32

Encycl. Brit., s.v. Kings (W.R.S.).

33

See Stade, i. 88-99; W. R. Smith, l. c.; Kreuz, Zeitschr. f. Wiss. Theol., 1877, p. 404. Some of the dates, as Dr. W. R. Smith shows, are "traditional," and are probably taken from Temple records (e. g., the invasion of Shishak, and the change of the revenue system in the twenty-third year of Joash). Taking these as data, we have (roughly) 160 years to the twenty-third year of Joash, + 160 to the death of Hezekiah, + 160 years to the return from the Exile = 480. He infers that "the existing scheme was obtained by setting down a few fixed dates, and filling up the intervals with figures in which 20 and 40 were the main units."

34

Speaker's Commentary, ii. 477.

35

1 Kings xiii. 1-32, xx. 13-15, 28, 35, 42; 2 Kings xxi. 10-15.

36

2 Kings xvii. 7-23, 32, 41, xxiii. 26, 27.

37

נְבִיאִים רֹאשׁוֹנִים. The three greater and twelve minor prophets are called prophetæ posteriores (אַחֲרוֹנִים). Daniel is classed among the Hagiographa (כְּתּוּבִים). This title of "former prophets" was, however, given by the Jews to the historic books from the mistaken fancy that they were all written by prophets.

38

Martensen, Dogmatics, p. 363.

39

2 Sam. vii. 12-16; 1 Kings xi. 36, xv. 4; 2 Kings viii. 19, xxv. 27-30. "His object evidently was," says Professor Robertson, "to exhibit the bloom and decay of the Kingdom of Israel, and to trace the influences which marked its varying destiny. He proceeds on the fixed idea that the promise given to David of a sure house remained in force during all the vicissitudes of the divided kingdom, and was not even frustrated by the fall of the kingdom of Judah."

40

1 Kings xi. 9-13.

41

Amos ix. 11, 12.

42

Psalm lxxxix. 48-50.

43

2 Kings xx. 16-18, xxii. 16-20.

44

Isa. xxx. 16.

45

Queen of the Air, p. 87.

46

Tac., Hist., 1, 2: "Opus aggredior opimum casibus, atrox prœliis, discors seditionibus, ipsa etiam pace sævum."

47

Wellhausen, History of Israel, p. 432; Stade, Gesch. des Volkes Israel, i., p. 12; Robinson, Ancient History of Israel, p. 15.

48

Od., ix. 51, 52.

49

Acts iv. 27, 28.

50

1 Cor. i. 26-28.

51

Id., v. 25.

52

Deut. xxvi. 5.

53

Isa. xxxviii. 17 (Heb.).

54

See Stade, i. 1-8.

55

1 Chron. xxiii. 1.

56

2 Sam. v. 5.

57

It is mentioned by Galen, vii.; Valesius, De Sacr. Philos., xxix., p. 187; Bacon, Hist. Vitæ et Mortis, ix. 25; Reinhard, Bibel-Krankheiten, p. 171. See Josephus, Antt., VII. xv. 3.

58

Now Solam, near Zerin (Jezreel), five miles south of Tabor (Robinson, Researches, iii. 462), on the south-west of Jebel el-Duhy (Little Hermon), Josh. xix. 18; 1 Sam. xxviii. 4.

59

Æsch., Sept. c. Theb., 690.

60

See Psalm cxxii. 3-5.

61

See Kittel, ii. 147.

62

The same word is rendered "worship" in Psalm xlv. 11. Comp. 2 Sam. ix. 6; Esth. iii. 2-5. In 1 Chron. xxix. 20 we are told that the people "worshipped" the Lord and the king.

63

"Μηδὲ βαρβάρου φωτὸς δίκηνΧαμαιπετὲς βόαμα προσχανῇς ἐμοί."Æsch., Agam., 887.64

Ecclus. xvi. 1-3. He must have had at least twenty sons, and at least one daughter (2 Sam. iii. 1-5, v. 14-16; 1 Chron. iii. 1-9, xiv. 3-7). Josephus again (Antt., VII. iii. 3) has a different list.

65

Kohanim.

66

From the fact that his son Eliada (2 Sam. v. 16) is called Beeliada (i. e., "Baal knows") in 1 Chron. xiv. 7, it is surely a precarious inference that "now and then he paid his homage to some Baal, perhaps to please one of his foreign wives" (Van Oort, Bible for Young People, iii. 84). The true explanation seems to be that at one time Baal, "Lord," was not regarded as an unauthorised title for Jehovah. The fact that David once had teraphim in his house (1 Sam. xix. 13, 16) shows that his advance in knowledge was gradual.

67

Chileab was either dead, or was of no significance.

68

2 Sam. xiii. 39. "The soul of king David longed to go forth unto Absalom."

69

Max. Tyr., Dissert., 9 (Keil, ad loc.).

70

In 2 Sam. xv. 7 we should certainly alter "forty" into four.

71

Rephaim seems a more probable reading than Ephraim in 2 Sam. xviii. 6; see Josh. xvii. 15, 18. Yet the name "Ephraim" may have been given to this transjordanic wood. The notion that he hung by his hair is only a conjecture, and not a probable one.

72

His three sons had pre-deceased him; his beautiful daughter Tamar (2 Sam. xiv. 27) became the wife of Rehoboam. She is called Maachah in 1 Kings xv. 2, and the LXX. addition to 2 Sam. xiv. 27 says that she bore both names. The so-called tomb of Absalom in the Valley of Hebron is of Asmonæan and Herodian origin.

73

Morier tells us that in Persia "runners" before the king's horses are an indispensable adjunct of his state.

74

The Stone of Zoheleth, probably a sacred stone – one of the numerous isolated rocks of Palestine; is not mentioned elsewhere. The Fuller's Fountain is mentioned in Josh. xv. 7, xviii. 16; 2 Sam. xvii. 17. It was south-east of Jerusalem, and is perhaps identical with "Job's Fountain," where the wadies of Kedron and Hinnom meet (Palestine Exploration Fund, 1874, p. 80).

75

Comp. 1 Kings i. 9-25.

76

The same phrase is used of Rehoboam (2 Chron. xii. 13, xiii. 7) when he was twenty-one, reading כא for מא, forty-one.

77

2 Sam. xii. 25: "And he sent by the hand of Nathan, the prophet; he called his name Jedidiah, because of the Lord" (A.V.). The verse is somewhat obscure. It either means that David sent the child to Nathan to be brought up under his guardianship, or sent Nathan to ask of the oracle the favour of some well-omened name (Ewald, iii. 168). Nathan was perhaps akin to David. The Rabbis absurdly identify him with Jonathan (1 Chron. xxvii. 32; 2 Sam. xxi. 21), nephew of David, son of Shimmeah.

78

1 Chron. xxii. 6-9.

79

LXX., Σαλωμών, and in Ecclus. xlvii. 13. Comp. Shelōmith (Lev. xxiv. 11), Shelōmi (Num. xxxiv. 27). But it became Σαλόμων in the New Testament, Josephus, the Sibylline verses, etc. The long vowel is retained in Salōme and in the Arabic Sūleyman, etc.

80

Among Solomon's adherents are mentioned "Shimei and Rei" (1 Kings i. 8), whom Ewald supposes to stand for two of David's brothers, Shimma and Raddai, and Stade to be two officers of the Gibborim. Thenius adopts a reading partly suggested by Josephus, "Hushai, the friend of David." Others identify Rei with Ira; a Shimei, the son of Elah, is mentioned among Solomon's governors (Nitzabim, 1 Kings iv. 18); and there was a Shimei of Ramah over David's vineyards (1 Chron. xxvii. 27). The name was common, and meant "famous."