полная версия

полная версияThe Bābur-nāma

d. The Bāburī-khat̤t̤ (Bābūr’s script).

So early as 910 AH. the year of his conquest of Kābul, Bābur devised what was probably a variety of nakhsh, and called it the Bāburī-khat̤t̤ (f. 144b), a name used later by Ḥaidar Mīrzā, Niz̤āmu’d-dīn Aḥmad and ‘Abdu’l-qādir Badāyūnī. He writes of it again (f. 179) s. a. 911 AH. when describing an interview had in 912 AH. with one of the Harāt Qāẓīs, at which the script was discussed, its specialities (mufradāt) exhibited to, and read by the Qāẓī who there and then wrote in it.2827 In what remains to us of the Bābur-nāma it is not mentioned again till 935 AH. (fol. 357b) but at some intermediate date Bābur made in it a copy of the Qorān which he sent to Makka.2828 In 935 AH. (f. 357b) it is mentioned in significant association with the despatch to each of four persons of a copy of the Translation (of the Wālidiyyah-risāla) and the Hindūstān poems, the significance of the association being that the simultaneous despatch with these copies of specimens of the Bāburī-khat̤t̤ points to its use in the manuscripts, and at least in Hind-āl’s case, to help given for reading novel forms in their text. The above are the only instances now found in the Bābur-nāma of mention of the script.

The little we have met with – we have made no search – about the character of the script comes from the Abūshqa, s. n. sīghnāq, in the following entry: —

Sīghnāq ber nū‘ah khat̤t̤ der Chaghatāīda khat̤t̤ Bāburī u ghairī kibī ki Bābur Mīrzā ash‘ār’nda kīlūr bait

Khūblār khat̤t̤ī naṣīb’ng būlmāsā Bābur nī tāng?Bāburī khat̤t̤ī aīmās dūr khat̤t̤ sīghnāqī mū dūr? 2829The old Osmanli-Turkish prose part of this appears to mean: – “Sīghnāq is a sort of hand-writing, in Chaghatāī the Bāburī-khat̤t̤ and others resembling it, as appears in Bābur Mīrzā’s poems. Couplet”: —

Without knowing the context of the couplet I make no attempt to translate it because its words khat̤t̤ or khaṭ and sīghnāq lend themselves to the kind of pun (īhām) “which consists in the employment of a word or phrase having more than one appropriate meaning, whereby the reader is often left in doubt as to the real significance of the passage.”2830 The rest of the rubā‘ī may be given [together with the six other quotations of Bābur’s verse now known only through the Abūshqa], in early Taẕkirātu ‘sh-shu‘āra of date earlier than 967 AH.

The root of the word sīghnāq will be sīq, pressed together, crowded, included, etc.; taking with this notion of compression, the explanations feine Schrift of Shaikh Effendi (Kunos) and Vambéry’s pétite écriture, the Sīghnāqī and Bāburī Scripts are allowed to have been what that of the Rāmpūr MS. is, a small, compact, elegant hand-writing. – A town in the Caucasus named Sīghnākh, “située à peu près à 800 mètres d’altitude, commença par être une forteresse et un lieu de refuge, car telle est la signification de son nom tartare.”2831 Sīghnāqī is given by de Courteille (Dict. p. 368) as meaning a place of refuge or shelter.

The Bāburī-khat̤t̤ will be only one of the several hands Bābur is reputed to have practised; its description matches it with other niceties he took pleasure in, fine distinctions of eye and ear in measure and music.

e. Is the Rāmpūr MS. an example of the Bāburī-khat̤t̤?

Though only those well-acquainted with Oriental manuscripts dating before 910 AH. (1504 AD.) can judge whether novelties appear in the script of the Rāmpūr MS. and this particularly in its head-lines, there are certain grounds for thinking that though the manuscript be not Bābur’s autograph, it may be in his script and the work of a specially trained scribe.

I set these grounds down because although the signs of a scribe’s work on the manuscript seem clear, it is “locally” held to be Bābur’s autograph. Has a tradition of its being in the Bāburī-khat̤t̤ glided into its being in the khat̤t̤-i-Bābur? Several circumstances suggest that it may be written in the Bāburī-khat̤t̤:– (1) the script is specially associated with the four transcripts of the Hindūstān poems (f. 357b), for though many letters must have gone to his sons, some indeed are mentioned in the Bābur-nāma, it is only with the poems that specimens of it are recorded as sent; (2) another matter shows his personal interest in the arrangement of manuscripts, namely, that as he himself about a month after the four books had gone off, made a new ruler, particularly on account of the head-lines of the Translation, it may be inferred that he had made or had adopted the one he superseded, and that his plan of arranging the poems was the model for copyists; the Rāmpūr MS. bearing, in the Translation section, corrections which may be his own, bears also a date earlier than that at which the four gifts started; it has its headlines ill-arranged and has throughout 13 lines to the page; his new ruler had 11; (3) perhaps the words taḥrīr qīldīm used in the colophon of the Rāmpūr MS. should be read with their full connotation of careful and elegant writing, or, put modestly, as saying, “I wrote down in my best manner,” which for poems is likely to be in the Bāburī-khat̤t̤.2832

Perhaps an example of Bābur’s script exists in the colophon, if not in the whole of the Mubīn manuscript once owned by Berézine, by him used for his Chréstomathie Turque, and described by him as “unique”. If this be the actual manuscript Bābur sent into Mā warā’u’n-nahr (presumably to Khwāja Aḥrārī’s family), its colophon which is a personal message addressed to the recipients, is likely to be autograph.

f. Metrical amusements.

(1) Of two instances of metrical amusements belonging to the end of 933 AH. and seeming to have been the distractions of illness, one is a simple transposition “in the fashion of the circles” (dawā’ir) into three measures (Rāmpūr MS. Facsimile, Plate XVIII and p. 22); the other is difficult because of the high number of 504 into which Bābur says (f. 330b) he cut up the following couplet: —

Gūz u qāsh u soz u tīlīnī mū dī?Qad u khadd u saj u bīlīnī mū dī?All manuscripts agree in having 504, and Bābur wrote a tract (risāla) upon the transpositions.2833 None of the modern treatises on Oriental Prosody allow a number so high to be practicable, but Maulānā Saifī of Bukhārā, of Bābur’s own time (f. 180b) makes 504 seem even moderate, since after giving much detail about rubā‘ī measures, he observes, “Some say there are 10,000” (Arūẓ-i-Saifī, Ranking’s trs. p. 122). Presumably similar possibilities were open for the couplet in question. It looks like one made for the game, asks two foolish questions and gives no reply, lends itself to poetic license, and, if permutation of words have part in such a game, allows much without change of sense. Was Bābur’s cessation of effort at 504 capricious or enforced by the exhaustion of possible changes? Is the arithmetical statement 9 × 8 × 7 = 504 the formula of the practicable permutations?

(2) To improvise verse having a given rhyme and topic must have demanded quick wits and much practice. Bābur gives at least one example of it (f. 252b) but Jahāngīr gives a fuller and more interesting one, not only because a rubā‘ī of Bābur’s was the model but from the circumstances of the game:2834– It was in 1024 AH. (1615 AD.) that a letter reached him from Māwarā’u’n-nahr written by Khwāja Hāshim Naqsh-bandī [who by the story is shown to have been of Aḥrārī’s line], and recounting the long devotion of his family to Jahāngīr’s ancestors. He sent gifts and enclosed in his letter a copy of one of Bābur’s quatrains which he said Ḥaẓrat Firdaus-makānī had written for Ḥaẓrat Khwājagī (Aḥrārī’s eldest son; f. 36b, p. 62 n. 2). Jahāngīr quotes a final hemistich only, “Khwājagīra mānda’īm, Khwājagīrā banda’īm” and thereafter made an impromptu verse upon the one sent to him.

A curious thing is that the line he quotes is not part of the quatrain he answered, but belongs to another not appropriate for a message between darwesh and pādshāh, though likely to have been sent by Bābur to Khwājagī. I will quote both because the matter will come up again for who works on the Hindūstān poems.2835

(1) The quatrain from the Hindūstān Poems is: —

Dar hawā’ī nafs gumrah ‘umr ẓāi‘ karda’īm [kanda’īm?];Pesh ahl-i-allāh az af‘āl-i-khūd sharmanda’īm;Yak naz̤r bā mukhlaṣān-i-khasta-dil farmā ki māKhwājagīrā mānda’īm u Khwājagīrā banda’īm.(2) That from the Akbar-nāma is: —

Darweshānrā agarcha nah as khweshānīm,Lek az dil u jān mu‘taqid eshānīm;Dūr ast magū‘ī shāhī az darweshī,Shāhīm walī banda-i-darweshānīm.The greater suitability of the second is seen from Jahāngīr’s answering impromptu for which by sense and rhyme it sets the model; the meaning, however, of the fourth line in each may be identical, namely, “I remain the ruler but am the servant of the darwesh.” Jahāngīr’s impromptu is as follows: —

Āī ānki marā mihr-i-tū besh az besh ast,Az daulat yād-i-būdat āī darwesh ast;Chandānki’z muẕẖ dahāt dilam shād shavadShadīm az ānki lat̤if az ḥadd besh ast.He then called on those who had a turn for verse to “speak one” i. e. to improvise on his own; it was done as follows: —

Dārīm agarcha shaghal-i-shāhī dar pesh,Har laḥz̤a kunīm yād-i-darweshān besh;Gar shād shavad’z mā dil-i-yak darwesh,Ānra shumarīm ḥaṣil-i-shāhī khwesh.R. – CHANDĪRĪ AND GŪĀLĪĀR

The courtesy of the Government of India enables me to reproduce from the Archæological Survey Reports of 1871, Sir Alexander Cunningham’s plans of Chandīrī and Gūālīār, which illustrate Bābur’s narrative on f. 333, p. 592, and f. 340, p. 607.

S. – CONCERNING THE BĀBUR-NĀMA DATING OF 935 AH

The dating of the diary of 935 AH. (f. 339 et seq.) is several times in opposition to what may be distinguished as the “book-rule” that the 12 lunar months of the Ḥijra year alternate in length between 30 and 29 days (intercalary years excepted), and that Muḥarram starts the alternation with 30 days. An early book stating the rule is Gladwin’s Bengal Revenue Accounts; a recent one, Ranking’s ed. of Platts’ Persian Grammar.

As to what day of the week was the initial day of some of the months in 935 AH. Bābur’s days differ from Wüstenfeld’s who gives the full list of twelve, and from Cunningham’s single one of Muḥarram 1st.

It seems worth while to draw attention to the flexibility, within limits, of Bābur’s dating, [not with the object of adversely criticizing a rigid and convenient rule for common use, but as supplementary to that rule from a somewhat special source], because he was careful and observant, his dating was contemporary, his record, as being de die in diem, provides a check of consecutive narrative on his dates, which, moreover, are all held together by the external fixtures of Feasts and by the marked recurrence of Fridays observed. Few such writings as the Bābur-nāma diaries appear to be available for showing variation within a year’s limit.

In 935 AH. Bābur enters few full dates, i. e. days of the week and month. Often he gives only the day of the week, the safest, however, in a diary. He is precise in saying at what time of the night or the day an action was done; this is useful not only as helping to get over difficulties caused by minor losses of text, but in the more general matter of the transference of a Ḥijra night-and-day which begins after sunset, to its Julian equivalent, of a day-and-night which begins at 12 a.m. This sometimes difficult transference affords a probable explanation of a good number of the discrepant dates found in Oriental-Occidental books.

Two matters of difference between the Bābur-nāma dating and that of some European calendars are as follows: —

a. Discrepancy as to the day of the week on which Muḥ. 935 AH. began.

This discrepancy is not a trivial matter when a year’s diary is concerned. The record of Muḥ. 1st and 2nd is missing from the Bābur-nāma; Friday the 3rd day of Muḥarram is the first day specified; the 1st was a Wednesday therefore. Erskine accepted this day; Cunningham and Wüstenfeld give Tuesday. On three grounds Wednesday seems right – at any rate at that period and place: – (1) The second Friday in Muḥarram was ‘Āshūr, the 10th (f. 240); (2) Wednesday is in serial order if reckoning be made from the last surviving date of 934 AH. with due allowance of an intercalary day to Ẕū’l-ḥijja (Gladwin), i. e. from Thursday Rajab 12th (April 2nd 1528 AD. f. 339, p. 602); (3) Wednesday is supported by the daily record of far into the year.

b. Variation in the length of the months of 935 AH.

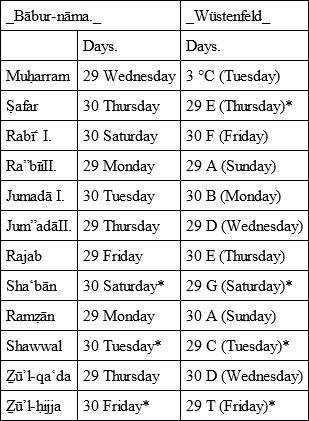

There is singular variation between the Bābur-nāma and Wüstenfeld’s Tables, both as to the day of the week on which months began, and as to the length of some months. This variation is shown in the following table, where asterisks mark agreement as to the days of the week, and the capital letters, quoted from W.’s Tables, denote A, Sunday; B, Tuesday, etc. (the bracketed names being of my entry).

The table shows that notwithstanding the discrepancy discussed in section a, of Bābur’s making 935 AH. begin on a Wednesday, and Wüstenfeld on a Tuesday, the two authorities agree as to the initial week-day of four months out of twelve, viz. Ṣafar, Sha‘bān, Shawwal and Ẕū’l-ḥijja.

Again: – In eight of the months the Bābur-nāma reverses the “book-rule” of alternative Muḥarram 30 days, Ṣafar 29 days et seq. by giving Muḥarram 29, Ṣafar 30. (This is seen readily by following the initial days of the week.) Again: – these eight months are in pairs having respectively 29 and 30 days, and the year’s total is 364. – Four months follow the fixed rule, i. e. as though the year had begun Muḥ. 30 days, Ṣafar 29 days – namely, the two months of Rabī‘ and the two of Jumāda. – Ramẓān to which under “book-rule” 30 days are due, had 29 days, because, as Bābur records, the Moon was seen on the 29th. – In the other three instances of the reversed 30 and 29, one thing is common, viz. Muḥarram, Rajab, Ẕū’l-qa‘da (as also Ẕū’l-ḥijja) are “honoured” months. – It would be interesting if some expert in this Musalmān matter would give the reasons dictating the changes from rule noted above as occurring in 935 AH.

c. Varia.

(1) On f. 367 Saturday is entered as the 1st day of Sha‘bān and Wednesday as the 4th, but on f. 368b stands Wednesday 5th, as suits the serial dating. If the mistake be not a mere slip, it may be due to confusion of hours, the ceremony chronicled being accomplished on the eve of the 5th, Anglicé, after sunset on the 4th.

(2) A fragment only survives of the record of Ẕū’l-ḥijja 935 AH. It contains a date, Thursday 7th, and mentions a Feast which will be that of the ‘Īdu’l-kabīr on the 10th (Sunday). Working on from this to the first-mentioned day of 936 AH. viz. Tuesday, Muḥarram 3rd, the month (which is the second of a pair having 29 and 30 days) is seen to have 30 days and so to fit on to 936 AH. The series is Sunday 10th, 17th, 24th (Sat. 30th) Sunday 1st, Tuesday 3rd.

Two clerical errors of mine in dates connecting with this Appendix are corrected here: – (1) On p. 614 n. 5, for Oct. 2nd read Oct. 3rd; (2) on p. 619 penultimate line of the text, for Nov. 28th read Nov. 8th.

T. – ON L: KNŪ (LAKHNAU) AND L: KNŪR (LAKHNŪR, NOW SHĀHĀBĀD IN RĀMPŪR)

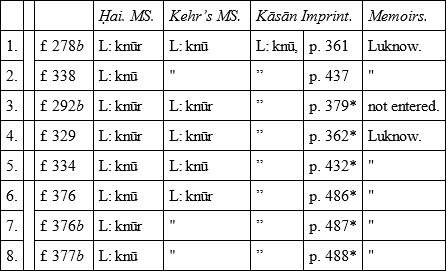

One or other of the above-mentioned names occurs eight times in the Bābur-nāma (s. a. 932, 934, 935 AH.), some instances being shown by their context to represent Lakhnau in Oudh, others inferentially and by the verbal agreement of the Ḥaidarābād Codex and Kehr’s Codex to stand for Lakhnūr (now Shāhābād in Rāmpūr). It is necessary to reconsider the identification of those not decided by their context, both because there is so much variation in the copies of the ‘Abdu’r-raḥīm Persian translation that they give no verbal help, and because Mr. Erskine and M. de Courteille are in agreement about them and took the whole eight to represent Lakhnau. This they did on different grounds, but in each case their agreement has behind it a defective textual basis. – Mr. Erskine, as is well known, translated the ‘Abdu’r-raḥīm Persian text without access to the original Turkī but, if he had had the Elphinstone Codex when translating, it would have given him no help because all the eight instances occur on folios not preserved by that codex. His only sources were not-first-rate Persian MSS. in which he found casual variation from terminal nū to nūr, which latter form may have been read by him as nūū (whence perhaps the old Anglo-Indian transliteration he uses, Luknow).2836– M. de Courteille’s position is different; his uniform Lakhnau obeyed the same uniformity in his source the Kāsān Imprint, and would appear to him the more assured for the concurrence of the Memoirs. His textual basis, however, for these words is Dr. Ilminsky’s and not Kehr’s. No doubt the uniform Lakhnū of the Kāsān Imprint is the result of Dr. Ilminsky’s uncertainty as to the accuracy of his single Turkī archetype [Kehr’s MS.], and also of his acceptance of Mr. Erskine’s uniform Luknow.2837– Since the Ḥaidarābād Codex became available and its collation with Kehr’s Codex has been made, a better basis for distinguishing between the L: knū and L: knūr of the Persian MSS. has been obtained.2838 The results of the collation are entered in the following table, together with what is found in the Kāsān Imprint and the Memoirs. [N.B. The two sets of bracketed instances refer each to one place; the asterisks show where Ilminsky varies from Kehr.]

The following notes give some grounds for accepting the names as the two Turkī codices agree in giving them: —

The first and second instances of the above table, those of the Ḥai. Codex f. 278b and f. 338, are shown by their context to represent Lakhnau.

The third (f. 292b) is an item of Bābur’s Revenue List. The Turkī codices are supported by B.M. Or. 1999, which is a direct copy of Shaikh Zain’s autograph T̤ābaqāt-i-bāburī, all three having L: knūr. Kehr’s MS. and Or. 1999 are descendants of the second degree from the original List; that the Ḥai. Codex is a direct copy is suggested by its pseudo-tabular arrangement of the various items. – An important consideration supporting L: knūr, is that the List is in Persian and may reasonably be accepted as the one furnished officially for the Pādshāh’s information when he was writing his account of Hindūstān (cf. Appendix P, p. liv). This official character disassociates it from any such doubtful spelling by the foreign Pādshāh as cannot but suggest itself when the variants of e. g. Dalmau and Bangarmau are considered. L: knūr is what three persons copying independently read in the official List, and so set down that careful scribes i. e. Kehr and ‘Abdu’l-lāh (App. P) again wrote L: knūr.2839– Another circumstance favouring L: knūr (Lakhnūr) is that the place assigned to it in the List is its geographical one between Saṃbhal and Khairābād. – Something for [or perhaps against] accepting Lakhnūr as the sarkār of the List may be known in local records or traditions. It had been an important place, and later on it paid a large revenue to Akbar [as part of Saṃbhal]. – It appears to have been worth the attention of Bīban Jalwānī (f. 329). – Another place is associated with L: knūr in the Revenue List, the forms of which are open to a considerable number of interpretations besides that of Baksar shown in loco on p. 521. Only those well acquainted with the United Provinces or their bye-gone history can offer useful suggestion about it. Maps show a “Madkar” 6 m. south of old Lakhnūr; there are in the United Provinces two Baksars and as many other Lakhnūrs (none however being so suitable as what is now Shāhābād). Perhaps in the archives of some old families there may be help found to interpret the entry L: knūr u B: ks:r (var.), a conjecture the less improbable that the Gazetteer of the Province of Oude (ii, 58) mentions a farmān of Bābur Pādshāh’s dated 1527 AD. and upholding a grant to Shaikh Qāẓī of Bīlgrām.

The fourth instance (f. 329) is fairly confirmed as Lakhnūr by its context, viz. an officer received the district of Badāyūn from the Pādshāh and was sent against Bīban who had laid siege to L: knūr on which Badāyūn bordered. – At the time Lakhnau may have been held from Bābur by Shaikh Bāyazīd

Farmūlī in conjunction with Aūd. Its estates are recorded as still in Farmūlī possession, that of the widow of “Kala Pahār” Farmūlī. – (See infra.)

The fifth instance (f. 334) connects with Aūd (Oudh) because royal troops abandoning the place L: knū were those who had been sent against Shaikh Bāyazīd in Aūd.

The remaining three instances (f. 376, f. 376b, f. 377b) appear to concern one place, to which Bīban and Bāyazīd were rumoured to intend going, which they captured and abandoned. As the table of variants shows, Kehr’s MS. reads Lakhnūr in all three places, the Ḥai. MS. once only, varying from itself as it does in Nos. 1 and 2. – A circumstance supporting Lakhnūr is that one of the messengers sent to Bābur with details of the capture was the son of Shāh Muḥ. Dīwāna whose record associates him rather with Badakhshān, and with Humāyūn and Saṃbhal [perhaps with Lakhnūr itself] than with Bābur’s own army. – Supplementing my notes on these three instances, much could be said in favour of reading Lakhnūr, about time and distance done by the messengers and by ‘Abdu’l-lah kitābdār, on his way to Saṃbhal and passing near Lakhnūr; much too about the various rumours and Bābur’s immediate counter-action. But to go into it fully would need lengthy treatment which the historical unimportance of the little problem appears not to demand. – Against taking the place to be Lakhnau there are the considerations (a) that Lakhnūr was the safer harbourage for the Rains and less near the westward march of the royal troops returning from the battle of the Goghrā; (b) that the fort of Lakhnau was the renowned old Machchi-bawan (cf. Gazetteer of the Province of Oude, 3 vols., 1877, ii, 366). – So far as I have been able to fit dates and transactions together, there seems no reason why the two Afghāns should not have gone to Lakhnūr, have crossed the Ganges near it, dropped down south [perhaps even intending to recross at Dalmau] with the intention of getting back to the Farmūlīs and Jalwānīs perhaps in Sārwār, perhaps elsewhere to Bāyazīd’s brother Ma‘rūf.

U. – THE INSCRIPTIONS ON BĀBUR’S MOSQUE IN AJODHYA (OUDH)

Thanks to the kind response made by the Deputy-Commissioner of Fyzābād to my husband’s enquiry about two inscriptions mentioned by several Gazetteers as still existing on “Bābur’s Mosque” in Oudh, I am able to quote copies of both.2840

a. The inscription inside the Mosque is as follows: —

1. Ba farmūda-i-Shāh Bābur ki ‘ādilashBanā’īst tā kākh-i-gardūn mulāqī,2. Banā kard īn muhbit̤-i-qudsiyānAmīr-i-sa‘ādat-nishān Mīr Bāqī3. Bavad khair bāqī! chū sāl-i-banā’īsh‘Iyān shud ki guftam, —Buvad khair bāqī (935).

The translation and explanation of the above, manifestly made by a Musalmān and as such having special value, are as follows: —2841

1. By the command of the Emperor Bābur whose justice is an edifice reaching up to the very height of the heavens,

2. The good-hearted Mīr Bāqī built this alighting-place of angels;2842

3. Bavad khāir bāqī! (May this goodness last for ever!)2843