полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The Bābur-nāma

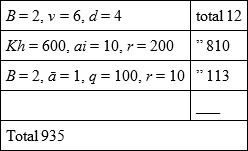

The year of building it was made clear likewise when I said, Buvad khair bāqī ( = 935).2844

The explanation of this is: —

1st couplet: – The poet begins by praising the Emperor Bābur under whose orders the mosque was erected. As justice is the (chief) virtue of kings, he naturally compares his (Bābur’s) justice to a palace reaching up to the very heavens, signifying thereby that the fame of that justice had not only spread in the wide world but had gone up to the heavens.

2nd couplet: – In the second couplet, the poet tells who was entrusted with the work of construction. M[i]r Bāqī was evidently some nobleman of distinction at Bābur’s Court. – The noble height, the pure religious atmosphere, and the scrupulous cleanliness and neatness of the mosque are beautifully suggested by saying that it was to be the abode of angels.

3rd couplet: – The third couplet begins and ends with the expression Buvad khair bāqī. The letters forming it by their numerical values represent the number 935, thus: —

The poet indirectly refers to a religious commandment (dictum?) of the Qorān that a man’s good deeds live after his death, and signifies that this noble mosque is verily such a one.

b. The inscription outside the Mosque is as follows: —

1. Ba nām-i-anki dānā hast akbarKi khāliq-i-jamla ‘ālam lā-makānī2. Durūd Muṣt̤afá ba‘d az sitāyishKi sarwar-i-aṃbiyā’ dū jahānī3. Fasāna dar jahān Bābur qalandarKi shud dar daur gītī kāmrānī. 2845The explanation of the above is as follows: —

In the first couplet the poet praises God, in the second Muḥammad, in the third Bābur. – There is a peculiar literary beauty in the use of the word lā-makānī in the 1st couplet. The author hints that the mosque is meant to be the abode of God, although He has no fixed abiding-place. – In the first hemistich of the 3rd couplet the poet gives Bābur the appellation of qalandar, which means a perfect devotee, indifferent to all worldly pleasures. In the second hemistich he gives as the reason for his being so, that Bābur became and was known all the world over as a qalandar, because having become Emperor of India and having thus reached the summit of worldly success, he had nothing to wish for on this earth.2846

The inscription is incomplete and the above is the plain interpretation which can be given to the couplets that are to hand. Attempts may be made to read further meaning into them but the language would not warrant it.

V. – BĀBUR’S GARDENS IN AND NEAR KĀBUL

The following particulars about gardens made by Bābur in or near Kābul, are given in Muḥammad Amīr of Kazwīn’s Pādshāh-nāma (Bib. Ind. ed. p. 585, p. 588).

Ten gardens are mentioned as made: – the Shahr-ārā (Town-adorning) which when Shāh-i-jahān first visited Kābul in the 12th year of his reign (1048 AH. -1638 AD.) contained very fine plane-trees Bābur had planted, beautiful trees having magnificent trunks,2847– the Chār-bāgh, – the Bāgh-i-jalau-khāna,2848– the Aūrta-bāgh (Middle-garden), – the Ṣaurat-bāgh, – the Bāgh-i-mahtāb (Moonlight-garden), – the Bāgh-i-āhū-khāna (Garden-of-the-deer-house), – and three smaller ones. Round these gardens rough-cast walls were made (renewed?) by Jahāngīr (1016 AH.).

The above list does not specify the garden Bābur made and selected for his burial; this is described apart (l. c. p. 588) with details of its restoration and embellishment by Shāh-i-jahān the master-builder of his time, as follows: —

The burial-garden was 500 yards (gaz) long; its ground was in 15 terraces, 30 yards apart(?). On the 15th terrace is the tomb of Ruqaiya Sult̤ān Begam2849; as a small marble platform (chabūṭra) had been made near it by Jahāngīr’s command, Shāh-i-jahān ordered (both) to be enclosed by a marble screen three yards high. – Bābur’s tomb is on the 14th terrace. In accordance with his will, no building was erected over it, but Shāh-i-jahān built a small marble mosque on the terrace below.2850 It was begun in the 17th year (of Shāh-i-jahān’s reign) and was finished in the 19th, after the conquest of Balkh and Badakhshān, at a cost of 30,000 rūpīs. It is admirably constructed. – From the 12th terrace running-water flows along the line (rasta) of the avenue;2851 but its 12 water-falls, because not constructed with cemented stone, had crumbled away and their charm was lost; orders were given therefore to renew them entirely and lastingly, to make a small reservoir below each fall, and to finish with Kābul marble the edges of the channel and the waterfalls, and the borders of the reservoirs. – And on the 9th terrace there was to be a reservoir 11 x 11 yards, bordered with Kābul marble, and on the 10th terrace one 15 x 15, and at the entrance to the garden another 15 x 15, also with a marble border. – And there was to be a gateway adorned with gilded cupolas befitting that place, and beyond (pesh) the gateway a square station,2852 one side of which should be the garden-wall and the other three filled with cells; that running-water should pass through the middle of it, so that the destitute and poor people who might gather there should eat their food in those cells, sheltered from the hardship of snow and rain.2853

1

Cf. Cap. II, PROBLEMS OF THE MUTILATED BABUR-NAMA and Tarīkh-i-rashīdi, trs. p. 174.

2

The suggestion, implied by my use of this word, that Babur may have definitely closed his autobiography (as Timur did under other circumstances) is due to the existence of a compelling cause viz. that he would be expectant of death as the price of Humayun’s restored life (p. 701).

3

Cf. p. 83 and n. and Add. Note, P. 83 for further emendation of a contradiction effected by some malign influence in the note (p. 83) between parts of that note, and between it and Babur’s account of his not-drinking in Herat.

4

Teufel held its title to be waqi‘ (this I adopted in 1908), but it has no definite support and in numerous instances of its occurrence to describe the acts or doings of Babur, it could be read as a common noun.

5

It stands on the reverse of the frontal page of the Haidarabad Codex; it is Timur-pulad’s name for the Codex he purchased in Bukhara, and it is thence brought on by Kehr (with Ilminski), and Klaproth (Cap. III); it is used by Khwafi Khan (d. cir. 1732), etc.

6

That Babur left a complete record much indicates beyond his own persistence and literary bias, e. g. cross-reference with and needed complements from what is lost; mention by other writers of Babur’s information, notably by Haidar.

7

App. H, xxx.

8

p. 446, n. 6. Babur’s order for the cairn would fit into the lost record of the first month of the year (p. 445).

9

Parts of the Babur-nama sent to Babur’s sons are not included here.

10

The standard of comparison is the 382 fols. of the Haidarabad Codex.

11

This MS. is not to be confused with one Erskine misunderstood Humayun to have copied (Memoirs, p. 303 and JRAS. 1900, p. 443).

12

For precise limits of the original annotation see p. 446 n. – For details about the E. Codex see JRAS. 1907, art. The Elph. Codex, and for the colophon AQR. 1900, July, Oct. and JRAS. 1905, pp. 752, 761.

13

See Index s. n. and III ante and JRAS. 1900-3-5-6-7.

14

Here speaks the man reared in touch with European classics; (pure) Turki though it uses no relatives (Radloff) is lucid. Cf. Cap. IV The Memoirs of Babur.

15

For analysis of a retranslated passage see JRAS. 1908, p. 85.

16

Tuzuk-i-jahangiri, Rogers & Beveridge’s trs. i, 110; JRAS. 1900, p. 756, for the Persian passage, 1908, p. 76 for the “Fragments”, 1900, p. 476 for Ilminski’s Preface (a second translation is accessible at the B.M. and I.O. Library and R.A.S.), Memoirs Preface, p. ix, Index s. nn. de Courteille, Teufel, Bukhara MSS. and Part iii eo cap.

17

For Shah-i-jahan’s interest in Timur see sign given in a copy of his note published in my translation volume of Gul-badan Begim’s Humayun-nama, p. xiii.

18

JRAS. 1900 p. 466, 1902 p. 655, 1905 art. s. n., 1908 pp. 78, 98; Index in loco s.n.

19

Cf. JRAS. 1900, Nos. VI, VII, VIII.

20

Ilminski’s difficulties are foreshadowed here by the same confusion of identity between the Babur-nama proper and the Bukhara compilation (Preface, Part iii, p. li).

21

Cf. Erskine’s Preface passim, and in loco item XI, cap. iv. The Memoirs of Baber, and Index s. n.

22

The last blow was given to the phantasmal reputation of the book by the authoritative Haidarabad Codex which now can be seen in facsimile in many Libraries.

23

But for present difficulties of intercourse with Petrograd, I would have re-examined with Kehr’s the collateral Codex of 1742 (copied in 1839 and now owned by the Petrograd University). It might be useful; as Kehr’s volume has lost pages and may be disarranged here and there.

The list of Kehr’s items is as follows: —

1 (not in the Imprint). A letter from Babur to Kamran the date of which is fixed as 1527 by its committing Ibrahim Ludi’s son to Kamran’s charge (p. 544). It is heard of again in the Bukhara Compilation, is lost from Kehr’s Codex, and preserved from his archetype by Klaproth who translated it. Being thus found in Bukhara in the first decade of the eighteenth century (our earliest knowledge of the Compilation is 1709), the inference is allowed that it went to Bukhara as loot from the defeated Kamran’s camp and that an endorsement its companion Babur-nama (proper) bears was made by the Auzbeg of two victors over Kamran, both of 1550, both in Tramontana.2854

2 (not in Imp.). Timur-pulad’s memo. about the purchase of his Codex in cir. 1521 (eo cap. post).

3 (Imp. 1). Compiler’s Preface of Praise (JRAS. 1900, p. 474).

4 (Imp. 2). Babur’s Acts in Farghana, in diction such as to seem a re-translation of the Persian translation of 1589. How much of Kamran’s MS. was serviceable is not easy to decide, because the Turki fettering of ‘Abdu’r-rahim’s Persian lends itself admirably to re-translation.2855

5 (Imp. 3). The “Rescue-passage” (App. D) attributable to Jahangir.

6 (Imp. 4). Babur’s Acts in Kabul, seeming (like No. 4) a re-translation or patching of tattered pages. There are also passages taken verbatim from the Persian.

7 (Imp. omits). A short length of Babur’s Hindustan Section, carefully shewn damaged by dots and dashes.

8 (Imp. 5). Within 7, the spurious passage of App. L and also scattered passages about a feast, perhaps part of 7.

9 (Imp. separates off at end of vol.). Translated passage from the Akbar-nāma, attributable to Jahangir, briefly telling of Kanwa (1527), Babur’s latter years (both changed to first person), death and court.2856

[Babur’s history has been thus brought to an end, incomplete in the balance needed of 7. In Kehr’s volume a few pages are left blank except for what shews a Russian librarian’s opinion of the plan of the book, “Here end the writings of Shah Babur.”]

10 (Imp. omits). Preface to the history of Humayun, beginning at the Creation and descending by giant strides through notices of Khans and Sultans to “Babur Mirza who was the father of Humayun Padshah”. Of Babur what further is said connects with the battle of Ghaj-davan (918-1512 q. v.). It is ill-informed, laying blame on him as if he and not Najm Sani had commanded – speaks of his preference for the counsel of young men and of the numbers of combatants. It is noticeable for more than its inadequacy however; its selection of the Ghaj-davan episode from all others in Babur’s career supports circumstantially what is dealt with later, the Ghaj-davani authorship of the Compilation.

11 (Imp. omits). Under a heading “Humayun Padshah” is a fragment about (his? Accession) Feast, whether broken off by loss of his pages or of those of his archetype examination of the P. Univ. Codex may show.

12 (Imp. 6). An excellent copy of Babur’s Hindustan Section, perhaps obtained from the Ahrari house. [This Ilminski places (I think) where Kehr has No. 7.] From its position and from its bearing a scribe’s date of completion (which Kehr brings over), viz. Tamt shud 1126 (Finished 1714), the compiler may have taken it for Humayun’s, perhaps for the account of his reconquest of Hind in 1555.

[The remaining entries in Kehr’s volume are a quatrain which may make jesting reference to his finished task, a librarian’s Russian entry of the number of pages (831), and the words Etablissement Orientale, Fr. v. Adelung, 1825 (the Director of the School from 1793).2857

24

See Gregorief’s “Russian policy regarding Central Asia”, quoted in Schuyler’s Turkistan, App. IV.

25

The Mission was well received, started to return to Petrograd, was attacked by Turkmans, went back to Bukhara, and there stayed until it could attempt the devious route which brought it to the capital in 1725.

26

One might say jestingly that the spirit in the book had rebelled since 1725 against enforced and changing masquerade as a phantasm of two other books!

27

Neither Ilminski nor Smirnov mentions another “Babur-nama” Codex than Kehr’s.

28

A Correspondent combatting my objection to publishing a second edition of the Memoirs, backed his favouring opinion by reference to ‘Umar Khayyam and Fitzgerald. Obviously no analogy exists; Erskine’s redundance is not the flower of a deft alchemy, but is the prosaic consequence of a secondary source.

29

The manuscripts relied on for revising the first section of the Memoirs, (i. e. 899 to 908 AH. -1494 to 1502 AD.) are the Elphinstone and the Ḥaidarābād Codices. To variants from them occurring in Dr. Kehr’s own transcript no authority can be allowed because throughout this section, his text appears to be a compilation and in parts a retranslation from one or other of the two Persian translations (Wāqi‘āt-i-bāburī) of the Bābur-nāma. Moreover Dr. Ilminsky’s imprint of Kehr’s text has the further defect in authority that it was helped out from the Memoirs, itself not a direct issue from the Turkī original.

Information about the manuscripts of the Bābur-nāma can be found in the JRAS for 1900, 1902, 1905, 1906, 1907 and 1908.

The foliation marked in the margin of this book is that of the Ḥaidarābād Codex and of its facsimile, published in 1905 by the Gibb Memorial Trust.

30

Bābur, born on Friday, Feb. 14th. 1483 (Muḥarram 6, 888 AH.), succeeded his father, ‘Umar Shaikh who died on June 8th. 1494 (Ramẓān 4, 899 AH.).

31

pād-shāh, protecting lord, supreme. It would be an anachronism to translate pādshāh by King or Emperor, previous to 913 AH. (1507 AD.) because until that date it was not part of the style of any Tīmūrid, even ruling members of the house being styled Mīrzā. Up to 1507 therefore Bābur’s correct style is Bābur Mīrzā. (Cf. f. 215 and note.)

32

See Āyīn-i-akbarī, Jarrett, p. 44.

33

The Ḥai. MS. and a good many of the W. – i-B. MSS. here write Aūtrār. [Aūtrār like Tarāz was at some time of its existence known as Yāngī (New).] Tarāz seems to have stood near the modern Auliya-ātā; Ālmālīgh, – a Metropolitan see of the Nestorian Church in the 14th. century, – to have been the old capital of Kuldja, and Ālmātū (var. Ālmātī) to have been where Vernoe (Vierny) now is. Ālmālīgh and Ālmātū owed their names to the apple (ālmā). Cf. Bretschneider’s Mediæval Geography p. 140 and T.R. (Elias and Ross) s. nn.

34

Mughūl u Aūzbeg jihatdīn. I take this, the first offered opportunity of mentioning (1) that in transliterating Turkī words I follow Turkī lettering because I am not competent to choose amongst systems which e. g. here, reproduce Aūzbeg as Ūzbeg, Özbeg and Euzbeg; and (2) that style being part of an autobiography, I am compelled, in pressing back the Memoirs on Bābur’s Turkī mould, to retract from the wording of the western scholars, Erskine and de Courteille. Of this compulsion Bābur’s bald phrase Mughūl u Aūzbeg jihatdīn provides an illustration. Each earlier translator has expressed his meaning with more finish than he himself; ‘Abdu’r-raḥīm, by az jihat ‘ubūr-i (Mughūl u) Aūzbeg, improves on Bābur, since the three towns lay in the tideway of nomad passage (‘ubūr) east and west; Erskine writes “in consequence of the incursions” etc. and de C. “grace aux ravages commis” etc.

35

Schuyler (ii, 54) gives the extreme length of the valley as about 160 miles and its width, at its widest, as 65 miles.

36

Following a manifestly clerical error in the Second W. – i-B. the Akbar-nāma and the Mems. are without the seasonal limitation, “in winter.” Bābur here excludes from winter routes one he knew well, the Kīndīrlīk Pass; on the other hand Kostenko says that this is open all the year round. Does this contradiction indicate climatic change? (Cf. f. 54b and note; A.N. Bib. Ind. ed. i, 85 (H. Beveridge i, 221) and, for an account of the passes round Farghāna, Kostenko’s Turkistān Region, Tables of Contents.)

37

Var. Banākat, Banākas̤, Fīākat, Fanākand. Of this place Dr. Rieu writes (Pers. cat. i, 79) that it was also called Shāsh and, in modern times, Tāshkīnt. Bābur does not identify Fanākat with the Tāshkīnt of his day but he identifies it with Shāhrukhiya (cf. Index s. nn.) and distinguishes between Tāshkīnt-Shāsh and Fanākat-Shāhrukhiya. It may be therefore that Dr. Rieu’s Tāshkīnt-Fanākat was Old Tāshkīnt, – (Does Fanā-kīnt mean Old Village?) some 14 miles nearer to the Saiḥūn than the Tāshkīnt of Bābur’s day or our own.

38

hech daryā qātīlmās. A gloss of dīgar (other) in the Second W. – i-B. has led Mr. Erskine to understand “meeting with no other river in its course.” I understand Bābur to contrast the destination of the Saiḥūn which he [erroneously] says sinks into the sands, with the outfall of e. g. the Amū into the Sea of Aral.

Cf. First W. – i-B. I.O. MS. 215 f. 2; Second W. – i-B. I.O. MS. 217 f. 1b and Ouseley’s Ibn Haukal p. 232-244; also Schuyler and Kostenko l. c.

39

Bābur’s geographical unit in Central Asia is the township or, with more verbal accuracy, the village i. e. the fortified, inhabited and cultivated oasis. Of frontiers he says nothing.

40

i. e. they are given away or taken. Bābur’s interest in fruits was not a matter of taste or amusement but of food. Melons, for instance, fresh or stored, form during some months the staple food of Turkistānīs. Cf. T.R. p. 303 and (in Kāshmīr) 425; Timkowski’s Travels of the Russian Mission i, 419 and Th. Radloff’s Réceuils d’Itinéraires p. 343.

N.B. At this point two folios of the Elphinstone Codex are missing.

41

Either a kind of melon or the pear. For local abundance of pears see Āyīn-i-akbarī, Blochmann p. 6; Kostenko and Von Schwarz.

42

qūrghān, i. e. the walled town within which was the citadel (ark).

43

Tūqūz tarnau sū kīrār, bū ‘ajab tūr kīm bīr yīrdīn ham chīqmās. Second W. – i-B. I.O. 217 f. 2, nuh jū’ī āb dar qila‘ dar mī āyid u īn ‘ajab ast kah hama az yak jā ham na mī bar āyid. (Cf. Mems. p. 2 and Méms. i, 2.) I understand Bābur to mean that all the water entering was consumed in the town. The supply of Andijān, in the present day, is taken both from the Āq Būrā (i. e. the Aūsh Water) and, by canal, from the Qarā Daryā.

44

khandaqnīng tāsh yānī. Second W. – i-B. I.O. 217 f. 2 dar kīnār sang bast khandaq. Here as in several other places, this Persian translation has rendered Turkī tāsh, outside, as if it were Turkī tāsh, stone. Bābur’s adjective stone is sangīn (f. 45b l. 8). His point here is the unusual circumstance of a high-road running round the outer edge of the ditch. Moreover Andijān is built on and of loess. Here, obeying his Persian source, Mr. Erskine writes “stone-faced ditch”; M. de C. obeying his Turkī one, “bord extérieur.”

45

qīrghāwal āsh-kīnasī bīla. Āsh-kīna, a diminutive of āsh, food, is the rice and vegetables commonly served with the bird. Kostenko i, 287 gives a recipe for what seems āsh-kīna.

46

b. 1440; d. 1500 AD.

47

Yūsuf was in the service of Bāī-sunghar Mīrzā Shāhrukhī (d. 837 AH. -1434 AD.). Cf. Daulat Shāh’s Memoirs of the Poets (Browne) pp. 340 and 350-1. (H.B.)

48

gūzlār aīl bīzkāk kūb būlūr. Second W. – i-B. (I.O. 217 f. 2) here and on f. 4 has read Turkī gūz, eye, for Turkī gūz or goz, autumn. It has here a gloss not in the Ḥaidarābād or Kehr’s MSS. (Cf. Mems. p. 4 note.) This gloss may be one of Humāyūn’s numerous notes and may have been preserved in the Elphinstone Codex, but the fact cannot now be known because of the loss of the two folios already noted. (See Von Schwarz and Kostenko concerning the autumn fever of Transoxiana.)

49

The Pers. trss. render yīghāch by farsang; Ujfalvy also takes the yīghāch and the farsang as having a common equivalent of about 6 kilomètres. Bābur’s statements in yīghāch however, when tested by ascertained distances, do not work out into the farsang of four miles or the kilomètre of 8 kil. to 5 miles. The yīghāch appears to be a variable estimate of distance, sometimes indicating the time occupied on a given journey, at others the distance to which a man’s voice will carry. (Cf. Ujfalvy Expédition scientifique ii, 179; Von Schwarz p. 124 and de C.’s Dict. s. n. yīghāch. In the present instance, if Bābur’s 4 y. equalled 4 f. the distance from Aūsh to Andijān should be about 16 m.; but it is 33 m. 1-3/4 fur. i. e. 50 versts. Kostenko ii, 33.) I find Bābur’s yīghāch to vary from about 4 m. to nearly 8 m.

50

āqār sū, the irrigation channels on which in Turkistān all cultivation depends. Major-General Gérard writes, (Report of the Pamir Boundary Commission, p. 6,) “Osh is a charming little town, resembling Islāmābād in Kāshmīr, – everywhere the same mass of running water, in small canals, bordered with willow, poplar and mulberry.” He saw the Āq Būrā, the White wolf, mother of all these running waters, as a “bright, stony, trout-stream;” Dr. Stein saw it as a “broad, tossing river.” (Buried Cities of Khotan, p. 45.) Cf. Réclus vi, cap. Farghāna; Kostenko i, 104; Von Schwarz s. nn.