полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The Bābur-nāma

Fuller particulars of it and of other items accompanying it are given in JRAS 1908 p. 828 et seq.

K. – AN AFGHĀN LEGEND

My husband’s article in the Asiatic Quarterly Review of April 1901 begins with an account of the two MSS. from which it is drawn, viz. I.O. 581 in Pushtū, I.O. 582 in Persian. Both are mainly occupied with an account of the Yūsuf-zāī. The second opens by telling of the power of the tribe in Afghānistān and of the kindness of Malik Shāh Sulaimān, one of their chiefs, to Aūlūgh Beg Mīrzā Kābulī, (Bābur’s paternal uncle,) when he was young and in trouble, presumably as a boy ruler.

It relates that one day a wise man of the tribe, Shaikh ‘Us̤mān saw Sulaimān sitting with the young Mīrzā on his knee and warned him that the boy had the eyes of Yazīd and would destroy him and his family as Yazīd had destroyed that of the Prophet. Sulaimān paid him no attention and gave the Mīrzā his daughter in marriage. Subsequently the Mīrzā having invited the Yūsuf-zāī to Kābul, treacherously killed Sulaimān and 700 of his followers. They were killed at the place called Siyāh-sang near Kābul; it is still known, writes the chronicler in about 1770 AD. (1184 AH.), as the Grave of the Martyrs. Their tombs are revered and that of Shaikh ‘Us̤mān in particular.

Shāh Sulaimān was the eldest of the seven sons of Malik Tāju’d-dīn; the second was Sult̤ān Shāh, the father of Malik Aḥmad. Before Sulaimān was killed he made three requests of Aūlūgh Beg; one of them was that his nephew Aḥmad’s life might be spared. This was granted.

Aūlūgh Beg died (after ruling from 865 to 907 AH.), and Bābur defeated his son-in-law and successor M. Muqīm (Arghūn, 910 AH.). Meantime the Yūsuf-zāī had migrated to Pashāwar but later on took Sawād from Sl. Wais (Ḥai. Codex ff. 219, 220b, 221).

When Bābur came to rule in Kābul, he at first professed friendship for the Yūsuf-zāī but became prejudiced against them through their enemies the Dilazāk2789 who gave force to their charges by a promised subsidy of 70,000 shāhrukhī. Bābur therefore determined, says the Yūsuf-zāī chronicler, to kill Malik2790 Aḥmad and so wrote him a friendly invitation to Kābul. Aḥmad agreed to go, and set out with four brothers who were famous musicians. Meanwhile the Dilazāk had persuaded Bābur to put Aḥmad to death at once, for they said Aḥmad was so clever and eloquent that if allowed to speak, he would induce the Pādshāh to pardon him.

On Aḥmad’s arrival in Kābul, he is said to have learned that Bābur’s real object was his death. His companions wanted to tie their turbans together and let him down over the wall of the fort, but he rejected their proposal as too dangerous for him and them, and resolved to await his fate. He told his companions however, except one of the musicians, to go into hiding in the town.

Next morning there was a great assembly and Bābur sat on the daïs-throne. Aḥmad made his reverence on entering but Bābur’s only acknowledgment was to make bow and arrow ready to shoot him. When Aḥmad saw that Bābur’s intention was to shoot him down without allowing him to speak, he unbuttoned his jerkin and stood still before the Pādshāh. Bābur, astonished, relaxed the tension of his bow and asked Aḥmad what he meant. Aḥmad’s only reply was to tell the Pādshāh not to question him but to do what he intended. Bābur again asked his meaning and again got the same reply.

Bābur put the same question a third time, adding that he could not dispose of the matter without knowing more. Then Aḥmad opened the mouth of praise, expatiated on Bābur’s excellencies and said that in this great assemblage many of his subjects were looking on to see the shooting; that his jerkin being very thick, the arrow might not pierce it; the shot might fail and the spectators blame the Pādshāh for missing his mark; for these reasons he had thought it best to bare his breast. Bābur was so pleased by this reply that he resolved to pardon Aḥmad at once, and laid down his bow.

Said he to Aḥmad, “What sort of man is Buhlūl Lūdī?” “A giver of horses,” said Aḥmad.

“And of what sort his son Sikandar?” “A giver of robes.”

“And of what sort is Bābur?” “He,” said Aḥmad, “is a giver of heads.”

“Then,” rejoined Bābur, “I give you yours.”

The Pādshāh now became quite friendly with Aḥmad, came down from his throne, took him by the hand and led him into another room where they drank together. Three times did Bābur have his cup filled, and after drinking a portion, give the rest to Aḥmad. At length the wine mounted to Bābur’s head; he grew merry and began to dance. Meantime Aḥmad’s musician played and Aḥmad who knew Persian well, poured out an eloquent harangue. When Bābur had danced for some time, he held out his hands to Aḥmad for a reward (bakhshīsh), saying, “I am your performer.” Three times did he open his hands, and thrice did Aḥmad, with a profound reverence, drop a gold coin into them. Bābur took the coins, each time placing his hand on his head. He then took off his robe and gave it to Aḥmad; Aḥmad took off his own coat, gave it to Adu the musician, and put on what the Pādshāh had given.

Aḥmad returned safe to his tribe. He declined a second invitation to Kābul, and sent in his stead his brother Shāh Manṣūr. Manṣūr received speedy dismissal as Bābur was displeased at Aḥmad’s not coming. On his return to his tribe Manṣūr advised them to retire to the mountains and make a strong sangur. This they did; as foretold, Bābur came into their country with a large army. He devastated their lands but could make no impression on their fort. In order the better to judge of its character, he, as was his wont, disguised himself as a Qalandar, and went with friends one dark night to the Mahūra hill where the stronghold was, a day’s journey from the Pādshāh’s camp at Dīārūn.

It was the ‘Īd-i-qurbān and there was a great assembly and feasting at Shāh Manṣūr’s house, at the back of the Mahūra-mountain, still known as Shāh Manṣūr’s throne. Bābur went in his disguise to the back of the house and stood among the crowd in the courtyard. He asked servants as they went to and fro about Shāh Manṣūr’s family and whether he had a daughter. They gave him straightforward answers.

At the time Musammat Bībī Mubāraka, Shāh Manṣur’s daughter was sitting with other women in a tent. Her eye fell on the qalandars and she sent a servant to Bābur with some cooked meat folded between two loaves. Bābur asked who had sent it; the servant said it was Shāh Manṣūr’s daughter Bībī Mubāraka. “Where is she?” “That is she, sitting in front of you in the tent.” Bābur Pādshāh became entranced with her beauty and asked the woman-servant, what was her disposition and her age and whether she was betrothed. The servant replied by extolling her mistress, saying that her virtue equalled her beauty, that she was pious and brimful of rectitude and placidity; also that she was not betrothed. Bābur then left with his friends, and behind the house hid between two stones the food that had been sent to him.

He returned to camp in perplexity as to what to do; he saw he could not take the fort; he was ashamed to return to Kābul with nothing effected; moreover he was in the fetters of love. He therefore wrote in friendly fashion to Malik Aḥmad and asked for the daughter of Shāh Manṣūr, son of Shāh Sulaimān. Great objection was made and earlier misfortunes accruing to Yūsuf-zāī chiefs who had given daughters to Aūlūgh Beg and Sl. Wais (Khān Mīrzā?) were quoted. They even said they had no daughter to give. Bābur replied with a “beautiful” royal letter, told of his visit disguised to Shāh Manṣūr’s house, of his seeing Bībī Mubāraka and as token of the truth of his story, asked them to search for the food he had hidden. They searched and found. Aḥmad and Manṣūr were still averse, but the tribesmen urged that as before they had always made sacrifice for the tribe so should they do now, for by giving the daughter in marriage, they would save the tribe from Bābur’s anger. The Maliks then said that it should be done “for the good of the tribe”.

When their consent was made known to Bābur, the drums of joy were beaten and preparations were made for the marriage; presents were sent to the bride, a sword of his also, and the two Maliks started out to escort her. They are said to have come from Thana by M‘amūra (?), crossed the river at Chakdara, taken a narrow road between two hills and past Talāsh-village to the back of Tīrī (?) where the Pādshāh’s escort met them. The Maliks returned, spent one night at Chakdara and next morning reached their homes at the Mahūra sangur.

Meanwhile Runa the nurse who had control of Malik Manṣūr’s household, with two other nurses and many male and female servants, went on with Bībī Mubāraka to the royal camp. The bride was set down with all honour at a large tent in the middle of the camp.

That night and on the following day the wives of the officers came to visit her but she paid them no attention. So, they said to one another as they were returning to their tents, “Her beauty is beyond question, but she has shewn us no kindness, and has not spoken to us; we do not know what mystery there is about her.”

Now Bībī Mubāraka had charged her servants to let her know when the Pādshāh was approaching in order that she might receive him according to Malik Aḥmad’s instructions. They said to her, “That was the pomp just now of the Pādshāh’s going to prayers at the general mosque.” That same day after the Mid-day Prayer, the Pādshāh went towards her tent. Her servants informed her, she immediately left her divan and advancing, lighted up the carpet by her presence, and stood respectfully with folded hands. When the Pādshāh entered, she bowed herself before him. But her face remained entirely covered. At length the Pādshāh seated himself on the divan and said to her, “Come Afghāniya, be seated.” Again she bowed before him, and stood as before. A second time he said, “Afghāniya, be seated.” Again she prostrated herself before him and came a little nearer, but still stood. Then the Pādshāh pulled the veil from her face and beheld incomparable beauty. He was entranced, he said again, “O, Afghāniya, sit down.” Then she bowed herself again, and said, “I have a petition to make. If an order be given, I will make it.” The Pādshāh said kindly, “Speak.” Whereupon she with both hands took up her dress and said, “Think that the whole Yūsuf-zāī tribe is enfolded in my skirt, and pardon their offences for my sake.” Said the Pādshāh, “I forgive the Yūsuf-zāī all their offences in thy presence, and cast them all into thy skirt. Hereafter I shall have no ill-feeling to the Yūsuf-zāī.” Again she bowed before him; the Pādshāh took her hand and led her to the divan.

When the Afternoon Prayer time came and the Pādshāh rose from the divan to go to prayers, Bībī Mubāraka jumped up and fetched him his shoes.2791 He put them on and said very pleasantly, “I am extremely pleased with you and your tribe and I have pardoned them all for your sake.” Then he said with a smile, “We know it was Malik Aḥmad taught you all these ways.” He then went to prayers and the Bībī remained to say hers in the tent.

After some days the camp moved from Dīārūn and proceeded by Bajaur and Tankī to Kābul.2792…

Bībī Mubāraka, the Blessed Lady, is often mentioned by Gul-badan; she had no children; and lived an honoured life, as her chronicler says, until the beginning of Akbar’s reign, when she died. Her brother Mīr Jamāl rose to honour under Bābur, Humāyūn and Akbar.

L. – ON MĀHĪM’S ADOPTION OF HIND-ĀL

The passage quoted below about Māhīm’s adoption of the unborn Hind-āl we have found so far only in Kehr’s transcript of the Bābur-nāma (i. e. the St. Petersburg Foreign Office Codex). Ilminsky reproduced it (Kāsān imprint p. 281) and de Courteille translated it (ii, 45), both with endeavour at emendation. It is interpolated in Kehr’s MS. at the wrong place, thus indicating that it was once marginal or apart from the text.

I incline to suppose the whole a note made by Humāyūn, although part of it might be an explanation made by Bābur, at a later date, of an over-brief passage in his diary. Of such passages there are several instances. What is strongly against its being Bābur’s where otherwise it might be his, is that Māhīm, as he always calls her simply, is there written of as Ḥaẓrat Wālida, Royal Mother and with the honorific plural. That plural Bābur uses for his own mother (dead 14 years before 925 AH.) and never for Māhīm. The note is as follows: —

“The explanation is this: – As up to that time those of one birth (tūqqān, womb) with him (Humāyūn), that is to say a son Bār-būl, who was younger than he but older than the rest, and three daughters, Mihr-jān and two others, died in childhood, he had a great wish for one of the same birth with him.2793 I had said ‘What it would have been if there had been one of the same birth with him!’ (Humāyūn). Said the Royal Mother, ‘If Dil-dār Āghācha bear a son, how is it if I take him and rear him?’ ‘It is very good’ said I.”

So far doubtfully might be Bābur’s but it may be Humāyūn’s written as a note for Bābur. What follows appears to be by some-one who knew the details of Māhīm’s household talk and was in Kābul when Dil-dār’s child was taken from her.

“Seemingly women have the custom of taking omens in the following way: – When they have said, ‘Is it to be a boy? is it to be a girl?’ they write ‘Alī or Ḥasan on one of two pieces of paper and Fāt̤ima on the other, put each paper into a ball of clay and throw both into a bowl of water. Whichever opens first is taken as an omen; if the man’s, they say a man-child will be born; if the woman’s, a girl will be born. They took the omen; it came out a man.”

“On this glad tidings we at once sent letters off.2794 A few days later God’s mercy bestowed a son. Three days before the news2795 and three days after the birth, they2796 took the child from its mother, (she) willy-nilly, brought it to our house2797 and took it in their charge. When we sent the news of the birth, Bhīra was being taken. They named him Hind-āl for a good omen and benediction.”2798

The whole may be Humāyūn’s, and prompted by a wish to remove an obscurity his father had left and by sentiment stirred through reminiscence of a cherished childhood.

Whether Humāyūn wrote the whole or not, how is it that the passage appears only in the Russian group of Bāburiana?

An apparent answer to this lies in the following little mosaic of circumstances: – The St. Petersburg group of Bāburiana2799 is linked to Kāmrān’s own copy of the Bābur-nāma by having with it a letter of Bābur to Kāmrān and also what may be a note indicating its passage into Humāyūn’s hands (JRAS 1908 p. 830). If it did so pass, a note by Humāyūn may have become associated with it, in one of several obvious ways. This would be at a date earlier than that of the Elphinstone MS. and would explain why it is found in Russia and not in Indian MSS.2800

[APPENDICES TO THE HINDŪSTĀN SECTION.]

M. – ON THE TERM BAḤRĪ QŪT̤ĀS

That the term baḥrī qūt̤ās is interpreted by Meninski, Erskine, and de Courteille in senses so widely differing as equus maritimus, mountain-cow, and bœuf vert de mer is due, no doubt, to their writing when the qūt̤ās, the yāk, was less well known than it now is.

The word qūt̤ās represents both the yāk itself and its neck-tassel and tail. Hence Meninski explains it by nodus fimbriatus ex cauda seu crinibus equi maritimi. His “sea-horse” appears to render baḥrī qūt̤ās, and is explicable by the circumstance that the same purposes are served by horse-tails and by yāk-tails and tassels, namely, with both, standards are fashioned, horse-equipage is ornamented or perhaps furnished with fly-flappers, and the ordinary hand-fly-flappers are made, i. e. the chowries of Anglo-India.

Erskine’s “mountain-cow” (Memoirs p. 317) may well be due to his munshī’s giving the yāk an alternative name, viz. Kosh-gau (Vigne) or Khāsh-gau (Ney Elias), which appears to mean mountain-cow (cattle, oxen).2801

De Courteille’s Dictionary p. 422, explains qūtās (qūt̤ās) as bœuf marin (baḥrī qūt̤ās) and his Mémoires ii, 191, renders Bābur’s baḥrī qūt̤ās by bœuf vert de mer (f. 276, p. 490 and n. 8).

The term baḥrī qūt̤ās could be interpreted with more confidence if one knew where the seemingly Arabic-Turkī compound originated.2802 Bābur uses it in Hindūstān where the neck-tassel and the tail of the domestic yāk are articles of commerce, and where, as also probably in Kābul, he will have known of the same class of yāk as a saddle-animal and as a beast of burden into Kashmīr and other border-lands of sufficient altitude to allow its survival. A part of its wide Central Asian habitat abutting on Kashmīr is Little Tibet, through which flows the upper Indus and in which tame yāk are largely bred, Skardo being a place specially mentioned by travellers as having them plentifully. This suggests that the term baḥrī qūt̤ās is due to the great river (baḥr) and that those of which Bābur wrote in Hindūstān were from Little Tibet and its great river. But baḥrī may apply to another region where also the domestic yāk abounds, that of the great lakes, inland seas such as Pangong, whence the yāk comes and goes between e. g. Yārkand and the Hindūstān border.

The second suggestion, viz. that “baḥrī qūt̤ās” refers to the habitat of the domestic yāk in lake and marsh lands of high altitude (the wild yāk also but, as Tibetan, it is less likely to be concerned here) has support in Dozy’s account of the baḥrī falcon, a bird mentioned also by Abū’l-faẓl amongst sporting birds (Āyīn-i-akbarī, Blochmann’s trs. p. 295): – “Baḥrī, espèce de faucon le meilleur pour les oiseaux de marais. Ce renseignment explique peut-être l’origine du mot. Marguerite en donne la même etymologie que Tashmend et le Père Guagix. Selon lui ce faucon aurait été appelé ainsi parce qu’il vient de l’autre côté de la mer, mais peut-être dériva-t-il de baḥrī dans le sens de marais, flaque, étang.”

Dr. E. Denison Ross’ Polyglot List of Birds (Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal ii, 289) gives to the Qarā Qīrghāwal (Black pheasant) the synonym “Sea-pheasant”, this being the literal translation of its Chinese name, and quotes from the Manchū-Chinese “Mirror” the remark that this is a black pheasant but called “sea-pheasant” to distinguish it from other black ones.

It may be observed that Bābur writes of the yāk once only and then of the baḥrī qūt̤ās so that there is no warrant from him for taking the term to apply to the wild yāk. His cousin and contemporary Ḥaidar Mīrzā, however, mentions the wild yāk twice and simply as the wild qūt̤ās.

The following are random gleanings about “baḥrī” and the yāk: —

(1) An instance of the use of the Persian equivalent daryā’ī of baḥrī, sea-borne or over-sea, is found in the Akbar-nāma (Bib. Ind. ed. ii, 216) where the African elephant is described as fīl-i-daryā’ī.

(2) In Egypt the word baḥrī has acquired the sense of northern, presumably referring to what lies or is borne across its northern sea, the Mediterranean.

(3) Vigne (Travels in Kashmīr ii, 277-8) warns against confounding the qūch-qār i. e. the gigantic moufflon, Pallas’ Ovis ammon, with the Kosh-gau, the cow of the Kaucasus, i. e. the yāk. He says, “Kaucasus (hodie Hindū-kush) was originally from Kosh, and Kosh is applied occasionally as a prefix, e. g. Kosh-gau, the yāk or ox of the mountain or Kaucasus.” He wrote from Skardo in Little Tibet and on the upper Indus. He gives the name of the female yāk as yāk-mo and of the half-breeds with common cows as bzch, which class he says is common and of “all colours”.

(4) Mr. Ney Elias’ notes (Tārīkh-i-rashīdī trs. pp. 302 and 466) on the qūt̤ās are of great interest. He gives the following synonymous names for the wild yāk, Bos Poëphagus, Khāsh-gau, the Tibetan yāk or Dong.

(5) Hume and Henderson (Lāhor to Yārkand p. 59) write of the numerous black yāk-hair tents seen round the Pangong Lake, of fine saddle yāks, and of the tame ones as being some white or brown but mostly black.

(6) Olufsen’s Through the Unknown Pamirs (p. 118) speaks of the large numbers of Bos grunniens (yāk) domesticated by the Kirghiz in the Pamirs.

(7) Cf. Gazetteer of India s. n. yāk.

(8) Shaikh Zain applies the word baḥrī to the porpoise, when paraphrasing the Bābur-nāma f. 281b.

N. – NOTES ON A FEW BIRDS

In attempting to identify some of the birds of Bābur’s lists difficulty arises from the variety of names provided by the different tongues of the region concerned, and also in some cases by the application of one name to differing birds. The following random gleanings enlarge and, in part, revise some earlier notes and translations of Mr. Erskine’s and my own. They are offered as material for the use of those better acquainted with bird-lore and with Himālayan dialects.

a. Concerning the lūkha, lūja, lūcha, kūja (f.135 and f.278b).

The nearest word I have found to lūkha and its similars is likkh, a florican (Jerdon, ii, 615), but the florican has not the chameleon colours of the lūkha (var.). As Bābur when writing in Hindūstān, uses such “book-words” as Ar. baḥrī (qūt̤ās) and Ar. bū-qalamūn (chameleon), it would not be strange if his name for the “lūkha” bird represented Ar. awja, very beautiful, or connected with Ar. loḥ, shining splendour.

The form kūja is found in Ilminsky’s imprint p.361 (Mémoires ii, 198, koudjeh).

What is confusing to translators is that (as it now seems to me) Bābur appears to use the name kabg-i-darī in both passages (f.135 and f.278b) to represent two birds; (1) he compares the lūkha as to size with the kabg-i-darī of the Kābul region, and (2) for size and colour with that of Hindūstān. But the bird, of the Western Himālayas known by the name kabg-i-darī is the Himālayan snow-cock, Tetraogallus himālayensis, Turkī, aūlār and in the Kābul region, chīūrtika (f.249, Jerdon, ii, 549-50); while the kabg-i-darī (syn. chikor) of Hindūstān, whether of hill or plain, is one or more of much smaller birds.

The snow-cock being 28 inches in length, the lūkha bird must be of this size. Such birds as to size and plumage of changing colour are the Lophophori and Trapagons, varieties of which are found in places suiting Bābur’s account of the lūkha.

It may be noted that the Himālayan snow-cock is still called kabg-i-darī in Afghānistān (Jerdon, ii, 550) and in Kashmīr (Vigne’s Travels in Kashmīr ii, 18). As its range is up to 18,000 feet, its Persian name describes it correctly whether read as “of the mountains” (dari), or as “royal” (darī) through its splendour.

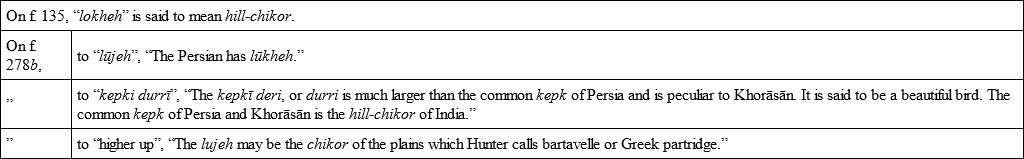

I add here the following notes of Mr. Erskine’s, which I have not quoted already where they occur (cf. f. 135 and f. 278b): —

The following corrections are needed about my own notes: – (1) on f. 135 (p. 213) n. 7 is wrongly referred; it belongs to the first word, viz. kabg-i-darī, of p. 214; (2) on f. 279 (p. 496) n. 2 should refer to the second kabg-i-darī.

b. Birds called mūnāl (var. monāl and moonaul).

Yule writing in Hobson Jobson (p. 580) of the “moonaul” which he identifies as Lophophorus Impeyanus, queries whether, on grounds he gives, the word moonaul is connected etymologically with Sanscrit muni, an “eremite”. In continuation of his topic, I give here the names of other birds called mūnāl, which I have noticed in various ornithological works while turning their pages for other information.