полная версия

полная версияThe Dog

The symptoms are not obscure. A dislike for wholesome food, and a craving for hotly spiced or highly sweetened diet, is an indication. Thirst and sickness are more marked. A love for eating string, wood, thread, and paper, denotes the fact; and is wrongly put down to the prompting of a mere mischievous instinct: any want of natural appetite, or any evidence of morbid desire in the case of food, declares the stomach to be disordered. The dog that, when offered a piece of bread, smells it with a sleepy eye, and without taking it licks the fingers that present it, has an impaired digestion. Such an animal will perhaps only take the morsel when it is about to be withdrawn; and, having got it, does not swallow it, but places it on the ground, and stands over it with an expression of peevish disgust. A healthy dog is always decided. No animal can be more so. It will often take that which it cannot eat, but, having done so, it either throws the needless possession away or lies down, and with a determined air watches "the property." There is no vexation in its looks, no captiousness in its manner. It acts with decision, and there is purpose in what it does. The reverse is the case with dogs suffering from indigestion. They are peevish and irresolute. They take only because another shall not have. They will perhaps eat greedily what they do not want if the cat looks longfully at that which had lain before them for many minutes, and which no coaxing could induce them to swallow. They are, in their foibles, very like the higher animal.

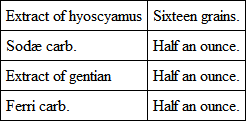

The treatment is simple. The dog must be put upon, and strictly kept upon, an allowance. Some persons, when these animals are sent to them, because the creatures are fat and sickly, shut the dogs up for two or four days, and allow them during the period to taste nothing but water. The trick often succeeds, but it is dangerous in severe cases, and needless in mild ones. This is a heartless practice, which ignorance only would resort to; but such conduct is very general, and the people who follow it boast laughingly of its effect. They do not care for its consequences. A weakly stomach cannot be benefited by a prolonged abstinence. I have kept a dog four-and-twenty hours without food, but never longer, and then only when the animal has been brought to me with a tale about its not eating. The report, then, is assurance that food has been offered, and the inference is that the stomach is loaded. A little rest enables it to get rid of its contents, and in some measure to recover its tone. The dog, as a general rule, does well on one meal a day; afterward, the food is regularly weighed, and nothing more than the quantity is permitted. This quantity may be divided into three or four meals, and given at stated periods, so that the last is eaten at night. When thus treated, animals, which I am assured would touch nothing, have soon become possessors of vigorous appetites. At the same time, exercise and the cold bath every morning is ordered; and either tonic or gentle sedatives, with alkalies and vegetable bitters, are administered. The following are the ordinary stomach-pills, and do very well for the generality of cases: —

Make into sixteen, thirty, or eight pills, and give two daily.

The reader, however, will not depend upon any one compound, for stomach disease is remarkably capricious. Sometimes one thing and sometimes another does a great deal of good; but the same thing is seldom equally good in any two cases. Stimulants, as nitrate of silver, trisnitrate of bismuth, or nux vomica, are occasionally of great service; and so also are purgatives and emetics, but these last, when they do no benefit, always do much injury. They should, therefore, be tried last, and then with caution, the order being thus: – Tonics, sedatives, and alkalies, either singly or in combination, and frequently changed. Stimulants and excitants in small doses, gradually increased. Emetics and purgatives, mingled with any of the foregoing. The food and exercise, after all, will do more for the restoration than the medicine, which must be so long continued that the mind doubts whether it is of any decided advantage. The affection is always chronic, and time is therefore imperative for its cure.

Dogs are afflicted with a disease of the stomach, which is very like to "water-brash," "pyrosis," or "cardialgia," in the human being. The animals thus tormented are generally fully grown and weakly: a peculiarity in the walk shows the strength is feeble. The chief symptom is, however, not to be mistaken. The creature is dull just before the attack: it gets by itself, and remains quiet. All at once it rises; and without an effort, no premonitory sounds being heard, a quantity of fluid is ejected from the mouth, and by the shaking of the head scattered about. This appears to afford relief, but the same thing may occur frequently during the day. This disease of itself is not dangerous; but it is troublesome, and will make any other disorder the more likely to terminate fatally; it should, therefore, be always attended to. The food must not be neglected, and either a solution of the iodide of potassium with liquor potassæ, or pills of trisnitrate of bismuth, must be given. The preparations of iron are sometimes of use; and a leech or two, after a small blister to the side, has also seemed to be beneficial. When some ground has been gained, the treatment recommended for indigestion generally must be adopted, the choice of remedies being guided by the symptoms. The practitioner, however, must not forget that the mode of feeding has probably been the cause; and, therefore, it must ever after be an object of especial care. The cold bath and exercise, proportioned to the strength, are equally to be esteemed.

Very old dogs often die from indigestion, and in such cases the stomach will become inflated to an extent that would hardly be credited. These animals I have not observed to be subject to flatulent colic; when, therefore, the abdomen becomes suddenly tympanitic the gas is usually contained in the stomach. Fits and diarrhœa may accompany or precede the attack, which in the first instance yields to treatment; but in a month more or less returns, and is far more stubborn. Ether and laudanum, by mouth and enema, are at first to be employed; and, generally, they are successful. The liquor potassæ, chloride of lime in solution, and aromatics with chalk, may also be tried, the food being strengthening but entirely fluid. The warm bath is here highly injurious; and bleeding or purging out of the question. When the distension of the stomach is so great as to threaten suffocation, the tube of the stomach-pump may be introduced; but, unless danger be present, the practitioner ought to depend upon the efforts of nature, to support which all his measures should be directed. After recovery, meat scraped as for potting, without any admixture of vegetables, must constitute the diet; and while a sufficiency is given, a very little only must be allowed at a time. With these precautions the life may be prolonged, but the restoration of health is not to be expected.

GASTRITIS

Dogs are abused for their depraved tastes, and reproached for the filth they eat; but if one of them, being of a particular disposition in the article of food, takes to killing his own mutton, he is knocked on the head as too luxurious. It is a very vulgar mistake to imagine the canine race have no preferences. They have their likes and dislikes quite as strong and as capricious as other animals. Man himself does not more frequently impair his digestion by over indulgence than does the dog. In both cases the punishment is the same, but the brute having the more delicate digestion suffers most severely. The dog's stomach is so subject to be deranged that few of these creatures can afford to gormandize; to which failing, however, they are much inclined. The consequence is soon shown. A healthy dog can make a hearty meal and sleep soundly after it. The petted favorite is often pained by a moderate quantity of food, and frequent are the housemaid's regrets that his digestion is not more retentive. He spoils other things besides victuals; and the more daintily he lives the more generally is he troublesome. It is the variety that diseases him. He grows to be omnivorous. He learns to relish that which nature did not fit him to consume, and as a consequence he pays for his bad habits. The dog in extreme cases can digest even bones; a banquet of tainted flesh will not disorder him; but he cannot subsist in health on his lady's diet. His stomach was formed to receive and assimilate certain substances, and to deny these is not to be generous or kind.

Gastritis is very common with ladies' favorites. Its symptoms are well marked. Frequent sickness is the first indication. This is taken little notice of. The mess is cleared up, and the matter is forgotten. Thirst is constant, and the lapping is long; but no further notice is taken of this circumstance, than to remark the animal has grown very fond of water. At last the thirst has increased, and no sooner is the draught swallowed than it is ejected. The appetite which may have been ravenous a little time before, now grows bad, and whatever is eaten is immediately returned. The animal is evidently ill. The nose is dry, and the breathing quick. It avoids warmth, and lies and pants, away from the hearthrug. It dislikes motion and stretches itself out, either upon its chest or on its belly. Sometimes it moans, and more rarely cries. The stomach is now inflamed; and if the symptoms could have been earlier understood, frequently has the animal been seen, prior to this stage of attack, licking the polished steel fire-irons. It has been horrifying its mistress's propriety, by its instinctive desire to touch something cold with its burning tongue; and the poor little beast perhaps has been chastised for seeking a momentary relief to its affliction.

Dogs that are properly treated rarely have gastritis. When they do, it is generally induced by some unwholesome food. I have known it to be caused by graves more often than by anything else they are accustomed to eat. I never recommend this stuff to be given to dogs. Meal and skim milk is far better, and that can always be procured where flesh is scarce. The entrails of sheep, &c., if washed and boiled with a large quantity of any kind of meal, are nutritious and wholesome; nay, even when a little tainted, they will not be refused. If, however, they were hung up in a strong draught, they would soon dry; and in that state might be preserved for use any length of time; all they afterwards require would be boiling. The paunch can be prepared in the same manner; and it would be worth some little trouble to avoid a mixture which contains nothing strengthening, and too often a great deal that is injurious.

The treatment of gastritis is simple. It is generally accompanied by more or less diarrhœa; but the violence of the leading symptom renders that of comparatively little consequence. The degree of sickness will always indicate whether the stomach is the principal seat of disease.

As nothing is retained, it would be a needless trouble to give many solids or fluids, by the mouth. From half a grain to a grain and a half of calomel, thoroughly mixed with the same quantities of powdered opium, may be sprinkled upon the tongue; and from one drachm to four drachms of sulphuric ether may be given in as much water as will dissolve it twenty minutes afterwards. The medicine will most probably be ejected; but, as it is very volatile, it may be retained sufficient time to have some influence in quieting the spasmodic irritability of the stomach. Ethereal injections should be administered every hour, and no food of any kind allowed. Besides this, from a quarter of a grain to a grain of opium may be sprinkled on the tongue every hour; and the ether draught continued until the sickness ceases, or the animal displays signs of being narcotised. An ammoniacal blister, if the symptoms are urgent, may be applied to the left side; but in mild cases, a strong embrocation will answer every purpose. Except the constitution be vigorous, and the pulse very strong, it will not be advisable to bleed, but from two to twelve leeches may be applied to the lower part of the chest. Cold water may be allowed in any quantity, but nothing warm should be given. The colder the water, the better, and the more grateful it will be to the animal. Where it can be obtained, a large lump of ice may be placed in the water, for the dog often will lick this, and sometimes even gnaw it. Small lumps of ice may be forced down as pills, and a cold bath may be given, the animal being well wrapped up afterwards, that it may become warm, and the blood, by the natural reaction, be determined to the skin.

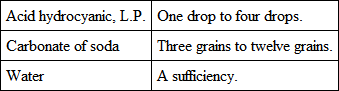

When the sickness is conquered, the following should be administered: —

The above may be repeated every four hours until the stomach is quiet; but it is not always tranquillized; sickness may return, and the pills may possibly seem to aggravate it. If such should appear to be the case, try the next: —

The ether and opium must also he persevered with, regulating the last of course by the action which it induces.

Food should consist of cold broth, slightly thickened with ground rice, arrowroot, starch, or flour, and for some days it must be composed of nothing more; but by degrees the thickness may be increased, and a little bread and milk introduced. After a time a small portion of minced underdone meat, without skin or fat, may be allowed; but the quantity must be small, and the quality unexceptionable.

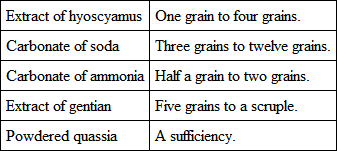

The second day generally sees an abatement of the more urgent symptoms, and then the draught may be composed of five minims of laudanum to every drachm of ether, and ten drachms of water. This to be given both by mouth and injection six times daily. The former pills were intended only to allay the primary violence of the disease, and when that object is attained, the following remedy may be employed: —

The above is for one pill, which should be repeated four times daily, and continued for some days; when, if the dog seems quite recovered, a course of the quinine tonic pills, as recommended for distemper, will be of use; but should any suspicion be created of the disorder not being entirely removed, the animal may be treated as advised for indigestion.

Sporting dogs are frequently sent to me suffering under what the proprietors are pleased to term "Foul." The history of these cases is soon known. They have been withdrawn from the field at the close of the season, and have ever since been shut up in close confinement, while the working diet has been persevered with. The poor beast is supposed capable of vegetating until the return of the period for shooting requires his services. He remains chained up till he acquires every outward disease to which his kind are liable; and then, when he stinks the place out, his owner is surprised at his condition, pronouncing his misused animal to be "very foul." "Foul" is not one disease, but an accumulation of disorders brought on by the absence of exercise with a stimulating diet. The sporting dog, when really at work, may have all the flesh it can consume; but at the termination of that period its food should consist wholly of vegetable substances, while a little exercise daily is necessary, not to health, but absolutely for life. The dog with "foul" requires each seat of disease to be treated separately; beginning of course with the dressing for mange or for lice, one or the other of which the animal is certain to display.

DISEASES DEPENDENT ON AN INTERNAL ORGAN

STOMACH. – ST. VITUS'S DANCE

This disease generally is assumed to be a nervous disorder, and so the symptoms declare it to be; but on post mortem examinations no lesion is found either upon the brain, spinal marrow, or the nerves themselves. This last circumstance, however, proves nothing; for the same thing may be said of tetanus in the human being, and of stringhalt in the horse; both of them being well-marked nervous affections. I append St. Vitus's Dance to the stomach, not because of that which I have not beheld, but because of that which I have positively seen.

It follows upon distemper. I do not know it as a distinct disorder, though it is asserted to exist as such when the greater or leading disease is unobserved. It then follows up the affection which primarily involves the stomach and intestines, and to which indications all other symptoms are secondary. On every post mortem which I have made of this disorder, I have discovered the stomach inflamed; and, therefore, not because the nerves or their centres are blank, but because on one important viscus I have found well marked signs to impress my reason, I propose to treat of this disorder as connected with the stomach.

The signs to which I allude, consists of patches of well-defined inflammation; and hence, knowing how distemper has the power to involve other organs, I conclude it has caused the spinal marrow to be sympathetically affected.

The symptoms of the disease are well marked. The poor beast, whether he be standing up or lying down, is constantly worried with a catching of the limb or limbs – for only one may be affected, or all four may be attacked. Sleeping or waking, the annoyance continues. The dog cannot obtain a moment's rest from its tormentor. Day and night the movement remains; no act, no position the poor brute is capable of, can bring to the animal an instant's downright repose. Its sleep is troubled and broken; its waking moments are rendered miserable by this terrible infliction. The worst of the matter is, that the dog in every other respect appears to be well. Its spirits are good, and it is alive for happiness. If it were released from its constant affliction, it is eager to enjoy its brief lease of life as in the time of perfect health. Plaintive and piteous are its looks as, lying asleep before the fire, it is aroused by a sudden pain; wakes, turns round, and mutely appeals to its master for an explanation or a removal of the nuisance. When stricken down at last, as, unable to stand, it lies upon its straw, most sad is it to see the poor head raised, and to hear the tail in motion welcoming any one who may enter the place in which it is a helpless but a necessary prisoner.

In this disorder the best thing is to pay every attention to the food. The wretched animal generally has an enormous appetite, and, when it is unable to stand, will continue feeding to the last. This morbid hunger must not be indulged. One pound of good rice may be boiled or cooked in a sufficiency of carefully made beef-tea, every particle of meat or bone being removed. This will constitute the provender for one day necessary to sustain the largest dog, and a quarter the amount will be sufficient for one of the average size. Where good rice is not to be obtained, oatmeal or bread, allowing for the moisture which the last contains, may be substituted. No bones, nor substances likely, when swallowed, to irritate the stomach, must on any account be allowed. The quantity given at one time must ever be small; and every sort of provender offered should be soft and soothing to the internal parts; though the poor dog will be eager to eat that which will be injurious. Water should be placed within its reach, and offered during the day, the head being held while the incapacitated animal drinks.

When a dog is prostrated by this affliction, it must on no account be suffered to remain on the floor, where its limbs would speedily become excoriated, being forcibly moved upon the boards; anything placed beneath the animal to save the limbs, would be saturated with the urine and fæces the poor beast is necessitated to pass. The best bed in such cases is made of a slanting piece of woodwork, of sufficient size to allow the animal to lie with ease at full length. The planks composing the wooden stage must be placed apart, be pierced with numerous holes, have the edges rounded, and be elevated at one end so as to allow all moisture readily to run off. The wood must be covered with a quantity of straw; which sort of bedding is convenient, not only because it allows the water to speedily percolate through it, but because it is warm, and being cheap, permits of repeated change.

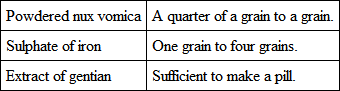

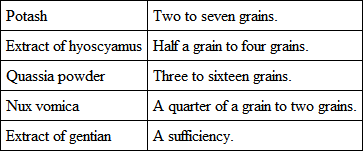

Physic is not of much avail in this disorder; kind nursing and mild food will do more towards recovery. Still, medicine, as an accessory, may be of considerable service, and in a secondary view deserves honorable mention. Alkalies, sedatives, and vegetable bitters, may be combined in various forms. The author's favorite sedative in stomach diseases is hyoscyamus, and alkali potash. For a bitter, quassia is a very good one; better than gentian, a small amount of the extract of which, however, may be used to make up the pill. When speaking of the pill, the most important ingredient must not be forgotten – I mean nux vomica. Some people employ strychnia, but such persons more often kill than cure their patients. Strychnia in any doses, however minute, is a violent poison to the dog. While at college I beheld animals killed with it; and there does not live the person who knows how to render this agent safe to the dog. Nux vomica, even, must be used in very minute doses, to be entirely safe – from a quarter of a grain to a small pup, to two grains to the largest animal. That quantity must be continued for a week, four pills being given daily; then add a quarter of a grain daily to the four larger pills, and a quarter of a grain every four days to all the smaller ones; keep on increasing the amount, till the physiological effects of the drug, as they are called, become developed. These consist in the beast having that which uninformed people term "a fit." He lies upon the ground, uttering rather loud cries, whilst every muscle of his body is in motion. Thus he continues scratching, as if it was his desire to be up and off at a hundred miles an hour. No sooner is he rid of one attack than he has another. He retains his consciousness, but is unable to give any sign of recognition. It is useless to crowd round the animal in this state; the drug must perform its office, and will do so, in spite of human effort. The very best thing that can be done, is to let the animal alone until the attack is over, when writers on Materia Medica tell us improvement is perceptible. I wish it was so in dogs. I have beheld the physiological effect of nux vomica repeatedly, but cannot recollect many instances in which I could date amendment from its appearance.

The following is the formula for the pill recently alluded to: —

The above quantities are sufficient for one pill, four of which are to be given daily for a week, at the expiration of which period the increase may begin. If the above, after a fair test has been made of it, does not succeed, trial may be instituted of the nitrate of silver, the trisnitrate of bismuth, or any of the various drugs said to be beneficial in the disease, or of service in stomach complaints. In this disorder the same drug never appears to act twice alike, therefore a change is warranted and desirable.

Hopes of restoration may be entertained if the animal can only be kept alive to recover strength; then confident expectation can be expressed that the dog will outgrow the disease. The first signs perceptible which denote recovery are these: – The provender the beast consumes is evidently not thrown away. Instead of eating much, and ungratefully becoming thinner and thinner upon that which it consumes, the animal displays a disposition to thrive upon its victuals. It does not get fat on what it eats, but it evidently loses no flesh. It grows no thinner; and if the strength be not recruited, it obviously is not diminished. The animal does not gorge much wholesome diet daily, to exhibit more and more the signs of debility and starvation. If only a suspicion can be felt that the poor dog does not sink, then hope of ultimate success may warm the heart of a kind master; but when the reverse is obvious, though killing a dog is next to killing a child – and he who for pleasure can do the one, is not far off from doing the other – yet it is mercy then to destroy that existence which must else be miserably worn away. When there is no chance left for expectation to cling to, it becomes real charity to do violence to our feelings, in order that we may spare a suffering creature pain; but when there is a prospect, however remote, of recovery, I hope there is no veterinary surgeon who would touch the life. When the animal can stand, we may anticipate good; and whatever is left of the complaint, we may assure our employers will vanish as the age increases; for St. Vitus's Dance is essentially the disease of young dogs. But as recovery progresses, we must be cautious to do nothing to fling the animal back. No walks must be enforced, under the pretence of administering exercise. The animal has enough of that in its ever-jerking limbs; and however well it may grow to be while the disease lasts, we may rest assured the dog suffering its attack stands in need of repose.