полная версия

полная версияThe Dog

The chest of the dog is not in any remarkable degree the seat of disease. The ribs of the animal being constructed for easy motion, and the muscles which move them being strong and large in proportion to the size of the bones, the lungs, therefore, are in general properly expanded; and this circumstance tends to preserve them in a healthy condition. They do not, however, always escape, but are subject to the same inflammations as those of the horse, though, from the causes stated, more rarely attacked.

Inflammation of the Lungs is denoted by a quickened pulse and breathing, preceded by shivering fits. The appetite does not always fail; in one or two instances I have seen it increased; but it is most often diminished. The animal is averse to motion; but when the affection is established, the dog sits upon its hocks, and wherever it is placed, speedily assumes that position. As the disorder becomes worse, the difficulty of breathing is more marked. The creature also shows a disposition to quit the house, and if there be an open window it will thrust its head through the aperture. The sense of suffocation is obviously present, and at length this becomes more and more obvious. The dog in the very last stage refuses to sit, but obstinately stands. One of the legs swells, and, on being felt, it is ascertained to be enlarged by fluid. There is dropsy of the chest, and the limb has sympathized in the disposition to effusion. The pulse denotes the weakness of the body; but the excitement of disease in a great measure disguises the other symptoms. The dog may even, to an unpractised eye, seem to possess considerable strength; for it resists, with all its remaining power, any attempt to move it, and its last energies are exerted to support the attitude that affords the most relief to the respiration. At length the poor brute stubbornly stands until forced to stir, when it drops suddenly, and for several moments lies as if the life had departed. Again it falls, but again revives; and always with the return of consciousness gets upon its legs; but at last it sinks, and without a struggle dies.

The lungs have been, in the first instance, inflamed, but the pleura or membrane covering the lungs, and also lining the chest, has likewise become by the progress of the disease involved. The cavity has become full of water, or rather serum, and by the pressure of the fluid the organs of respiration are compressed. It is seldom that both sides are gorged to an equal degree; but one cavity may be quite full while the other is only partially so. One lung, therefore, in part remains to perform the function on which the continuance of life depends; and if, by any movement, the weight of fluid is brought to bear upon the little left to continue respiration, the animal is literally asphyxiated. It drops, in fact, strangled, or more correctly, suffocated; and as the vital energy is strong or weak, so may the dog more or less frequently recover for a time. In the end, however, the tax upon the strength exhausts the power, and the accumulation of the fluid diminishes the source by which the life was sustained. After death, I have taken from the body of a full-sized Newfoundland one lung, which lay with ease upon my extended hand; while the two held together afforded a surface sufficient to support the other. The condensation was so great that the part was literally consolidated, and the fluid which exuded on cutting into the substance was small in quantity. The blood-vessels were, with the air-cells, compressed, and while the arterialization of the blood was imperfect, the circulation was also impeded.

The causes usually assigned to account for inflammation of the lungs will not, in the dog, explain its origin. I have usually met it where the animal had not been exposed to wet or cold; where it had not undergone excessive exertion, or been subjected to violence. Extraordinary care as rather seemed to induce, than the neglect of the creature appeared to provoke the attack. It is, however, easy to trace causes when we have a wish to explain a particular effect; but where the lungs have been inflamed I have never, to my entire satisfaction, been able to ascertain that the animal had been exposed to hardship, or subjected to labor which it had not previously sustained, and which, if the health had been good, it might not have endured.

Disease of the lungs is, in the early stage, very readily subdued; but, if allowed to establish itself, it is rarely that medicine can eradicate it. The majority of persons who profess to know anything about the diseases of dogs, look upon the nose as an indication of the health. While the appetite is good, or the nose is cold and moist, such people are confident no fear need be entertained. Of the uncertainty that attends the disposition to feed mention has been already made; but with regard to the condition of a part, the persons who assume to teach us are likely to be in such cases entirely deceived. I have known dogs with violent inflammation of the lungs; I have seen them die from dropsy of the chest; and their noses have been wet and cold, even as though the animals had iced the organs. From this mistaken notion, therefore, no doubt, are to be traced the numerous instances of dogs brought for treatment when no remedies can be of avail. They are submitted to our notice only that we may be pained to look upon their deaths; and often have my endeavors been thus limited to simple palliative measures, when an earlier application would have enabled me to employ medicine with a reasonable prospect of success.

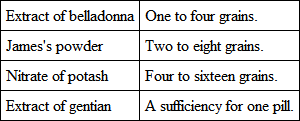

In the commencement, when the breathing is simply increased and the pulse slightly accelerated, then if you place the ear to the side, there is merely a small increase of sound; and the animal exhibits no obstinate, or more properly, unconquerable disposition to sit upon the hocks; small quantities of belladonna, combined with James's powder, will generally put an end to the disease. The belladonna, in doses of from one to four grains, may be given three times a day; but where trouble is not objected to, and regularity can be depended upon, I prefer administering it in doses of a quarter of a grain to a grain every hour. By the last practice I think I have obtained results more satisfactory; but it is not always that a plan necessitating almost constant attention can be enforced, or that the animal to be treated will allow of such repeated interference. The following formula will serve the purpose, and the reader can divide it if the method I recommend can be pursued.

If, on the second day, no marked improvement is perceptible, small doses of antimonial wine may be tried; from fifteen minims to half-a-drachm may be given every fourth hour, unless vomiting be speedily induced; when the next dose must, at the stated period, be reduced five or ten minims, and even further diminished if the lessened quantity should have an emetic effect. The object in giving the antimonial wine is to create nausea, and not to excite sickness; and we endeavor to keep up the action in order to affect the system. This is frequently very decisive in the reduction of the symptoms; but, even after the danger has been dispelled, the pills before recommended must be persevered with, and every means adopted to prevent a relapse.

Sometimes, however, the disorder commences with a violence that, from the very beginning of the attack, calls for the most energetic measures. If the breathing be very quick, short, and catching; the position constant; the pulse full and strong; the jugular vein may be opened, and from one ounce to eight ounces of blood extracted; or leeches may be applied to the sides; or an ammoniacal blister may be employed. This is done by saturating a piece of rag, folded three or four times, with a solution composed of liquor ammoniaca fort., one part; distilled water, three parts; and, having placed it upon the place from which the hair has been previously cut off, holding over it a dry cloth to prevent evaporization of the volatile vesicant. A quarter of an hour will serve to raise the cuticle; but frequently that object is accomplished in less time; therefore, during its operation, the agent must be watched, or else the effect may be greater than we desire, and sloughing may ensue.

A dose of castor oil may also be administered, and the food should be composed entirely of vegetables, if the animal can be induced to eat this kind of diet. Exertion should be prevented, and quiet as much as possible enjoined. The tincture of aconite, it is said, sometimes does wonders in inflammation of the lungs; but in my hands its operation has been uncertain, though the homœopathists trust greatly to its action in this disease. They give it singly, but I have not reaped from its use on the dog those advantages which tempt me to depend solely on its influence. When employed, it may be given in doses of from half a drop to two drops of the tincture, in any pleasant vehicle, every hour.

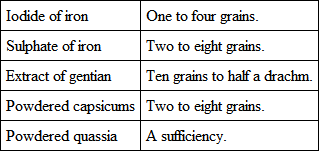

After dropsy of the chest has been established, the chance of cure is certainly remote; but tapping at all events renders the last moments of life more easy. It is both simple and safe, and does not seem to occasion any pain; but, on the contrary, to afford immediate relief. The skin should be first punctured, and then drawn forward so as to bring the incision over the spot where the instrument is to be inserted. The place where the trocar should be introduced is between the seventh and eighth ribs, nearer to the last than to the first, and rather close to the breast-bone. The point being selected, the instrument is pushed gently into the flesh; and when the operator feels no resistance is offered to the progress of the tube, he knows the cavity has been pierced. The stilet is then withdrawn, and the fluid will pour forth. Unless the dog shows signs of faintness, as much of the water as possible ought to be taken away; but if symptoms of syncope appear, the operation must be stopped, and after a little time, when the strength has been regained, resumed. When this has been done, tonics must be freely resorted to. The following pill may be administered three or four times a day; and the diet should be confined to flesh, for everything depends on the invigoration of the body, and the inflammation is either gone, or it has become of secondary importance.

The above will make two pills; and it is better to make these the more frequently, as they speedily harden, and we now desire their quickest effect, which is sooner obtained if they are soft or recently compounded.

During recovery the food must be mild, and tonics must be administered. Exercise should be allowed with the greatest caution, and all excitement ought to be avoided. The dog must be watched and nursed, being provided with a sheltered lodging and an ample bed in a situation perfectly protected from winds or draughts, but at the same time cool and airy.

Asthma is a frequent disease in old and petted dogs. It comes on by fits, and, through the severity of the attack, often seems to threaten suffocation; but I have not known a single case in which it has proved fatal. The cause is generally attributable to inordinate feeding, for the animals thus afflicted are always gross and fat. The disorder comes on gradually in most instances, though the fit is usually sudden. The appetite is not affected, or rather it is increased often to an extraordinary degree. The craving is great, and flesh is always preferred, while sweet and seasoned articles are much relished. On examination, the signs denoting the digestion to be deranged will be discovered. Piles are nearly constantly met with; the coat is generally in a bad condition, and the hair off in places. The nose may be dry; the membrane of the eyes congested; the teeth covered with tartar, and the breath offensive. The dog is slothful, and exertion is followed by distress. Cough may or may not exist; but it usually appears towards the latter period of the attack.

Asthma is spasm of the bronchial tubes, and when it is thoroughly established it is seldom to be cured. All medicine can accomplish is the relief of the more violent symptoms. The fits may be rendered comparatively less frequent and less severe; but the agents that best operate to that result are likely in the end to destroy the general health. Between two evils, therefore, the proprietor has to make his choice; but if he resolves to treat the disorder, he must do so knowing the drugs he makes use of are not entirely harmless.

Food is of all importance. It must be proportioned to the size of the patient, and be rather spare than full in quantity. Flesh should be denied, and coarse vegetable diet alone allowed. The digestion must also be attended to, and every means taken to invigorate the system. Exercise must be enforced, even though the animal appear to suffer in consequence of being made to walk. The skin should be daily brushed, and the bed should not be too luxurious. Sedatives are of service; and as no one of these agents will answer in every case, a constant change will be needed, that, by watching their action, the one which produces the best effect may be discovered. Opium, belladonna, hyoscyamus, assafœtida, and the rest, may be thus tried in succession; and often small doses produce those effects which the larger one seems to conceal. A pill containing any sedative, with an alterative quantity of some expectorant, may be given three times daily; but when the fit is on, I have gained the most immediate benefit by the administration of ether and opium. From one to four leeches to the chest, sometimes, are of service; but small ammoniacal blisters applied to the sides, and frequently repeated, are more to be depended upon. Trivial doses of antimonial wine or ipecacuanha wine, with an occasional emetic, will sometimes give temporary ease; but the last-named medicines are to be resorted to only after due consideration, as they greatly lower the strength. Stomachics and mild tonics at the same time are to be employed; but a cure is not to be expected. The treatment cannot be absolutely laid down; but the judgment must be exercised, and whenever the slightest improvement is remarked every effort must be made to prevent a relapse.

HEPATITIS

Liver complaints were once fashionable. A few years ago the mind of Great Britain was in distress about its bile, and blue pill with black draught literally became a part of the national diet. At present nervous and urinary diseases appear to be in vogue; but, with dogs, hepatic disorders are as prevalent as ever. The canine liver is peculiarly susceptible to disease. Very seldom have I dipped into the mysteries of their bodies but I have found the biliary gland of these animals deranged; sometimes inflamed – sometimes in an opposite condition – often enlarged – seldom diminished – rarely of uniform color – occasionally tuberculated – and not unfrequently as fat with disease as those are which have obtained for Strasburg geese a morbid celebrity.

It is, however, somewhat strange that, notwithstanding the almost universality of liver disease among petted dogs, the symptoms which denote its existence are in these creatures so obscure and undefined as rarely to be recognised. Very few dogs have healthy livers, and yet seldom is the disordered condition of this important gland suspected. Various are the causes which different authors, English and foreign, have asserted produced this effect. I shall only allude to such as I can on my own experience corroborate, and here I shall have but little to refer to. Over-feeding and excessive indulgence are the sources to which I have always traced it. In the half-starved or well-worked dog I have seen the liver involved; but have never beheld it in such a state as led me to conclude it was the principal or original seat of the affection which ended in death. On the other hand, in fatted and petted animals, I have seen the gland in a condition that warranted no doubt as to what part the fatal attack had commenced in.

When death has been the consequence of hepatic disorder, the symptoms have in every instance been chronic. I am not aware that I have been called upon to treat a case of an acute description, excepting as a phase of distemper. It would be too much to say such a form of disease does not exist in a carnivorous animal; but I have hitherto not met with it. Neither have I seen it as the effect of inveterate mange; though I have beheld obstinate skin disease the common, but far from invariable, result of chronic hepatitis. I have also known cerebral symptoms to be produced by the derangement of this gland, which, in the dog, may be the cause of almost any possible symptom, and still give so little indication of its actual condition as almost to set our reason at defiance.

When the animal is fat, the visible mucous membranes may be pallid; the tongue white; the pulse full and quick; the spirits slothful: the appetite good; the fœces natural: the bowels irregular; the breath offensive; the anus enlarged, and the rump denuded of hair, the naked skin being covered with a scaly cuticle, thickened and partially insensible.

When the animal is thin, almost all of the foregoing signs may be wanting. The dog may be only emaciated – a living skeleton, with an enlarged belly. It is dull, and has a sleepy look when undisturbed; but when its attention is attracted, the expression of its countenance is half vacant and half wild. The pupil of the eye is dilated, and the visual organs stare as though the power of recognition were enfeebled. The appetite is good and the manner gentle. The tongue is white, and occasionally reddish towards the circumference. The membranes of the eye are very pale, but not yellow. The lining of the mouth is of a faint dull tint, and often it feels cold to the touch. The coat looks not positively bad; but rather like a skin which had been well dressed by a furrier, than one which was still upon a living body.

The history in these cases invariably informs us that the animal has been fat – very fat – about six or twelve months ago. It fell away all at once, though no change was made in the diet; and yet we learn it has been physicked. No restraint has been put upon buckthorn, castor oil, aloes, sulphur, and antimony, but yet the belly will not go down – it keeps getting bigger; and now we are told the animal has a dropsy which "wants to be cured." It is natural the figure and condition should suggest the idea of ascites; but the hair does not pull out – none of the legs are swollen – the shape of the abdomen wants the appearance of gravitation, and if the patient be placed upon its back the form of the rotundity is not altered by the position of the body. Moreover, the breathing is tolerably easy: and, though if one hand be placed against the side of the belly, and the part opposite be struck with the other, there will be a marked sense of fluctuation; still we cannot accept so dubious a test against the mass of evidence that declares dropsy is not the name of the disease. To make sure, we feel the abdomen near to the line of the false ribs. This gives no pain, so we press a little hard, and in two or three places on either side, on the right, or may be the left, high up or low down; for in abnormal growths there can be no rule – in two or three places we can detect hard, solid, but smooth lumps within the cavity. This last discovery leaves no room for further doubt, so we pronounce the liver to be the organ that is principally affected. In chronic cases, especially after the dog has begun to waste, enlargement nearly always may be felt, not invariably hard, yet often so, but never soft or so soft as the other parts; and this proof should, therefore, in every instance of the kind be sought for.

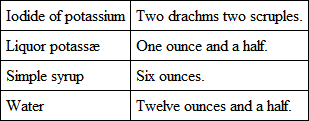

With regard to treatment, the food must not be suddenly reduced to the starvation point. Whether the dog be fat or lean, let the quality be nutritious, and the quantity sufficient; from a quarter of a pound to a pound and a half of paunch, divided into four meals, will be enough for a single day; but nothing more than this must be given. Tonics, to strengthen the system generally, should be employed; and an occasional dose of the cathartic pills administered, providing the condition is such as justifies the use of purgatives. Frequent small blisters, applied over the region of the liver, may do good; but they should not be larger than two or four inches across, and they should be repeated one every three or four days. Leeches put upon the places where hardness can be felt, also are beneficial; but depletion must be regulated by the ability of the animal to sustain it. A long course of iodide of potassium in solution, combined with the liquor potassæ, will, however, constitute the principal dependence.

Give from half a teaspoonful to a teaspoonful three times a day.

The above must be persevered in for a couple of months before any effect can be anticipated. Mercury I have not found of any service, though Blaine speaks highly of it, and Youatt quotes his opinion. Perhaps I have not employed it rightly, or ventured to push it far enough.

Under the treatment recommended, the dog may be preserved from speedy death; but the structures have been so much changed that medicine cannot be expected to restore them. The pet may be saved to its indulgent mistress, and again perhaps exhibit all the charms for which it was ever prized; but the sporting-dog will never be made capable of doing work, and certainly it is not to be selected to breed from after it has sustained an attack of hepatitis.

Sometimes, during the existence of hepatitis, the animal will be seized with fits of pain, which appear to render it frantic. These I always attribute to the passage of gall stones, which I have taken in comparative large quantities from the gall-bladders of dogs. The cries and struggles create alarm, but the attack is seldom fatal. A brisk purgative, a warm bath, and free use of laudanum and ether, afford relief; for when the animal dies of chronic hepatitis, it perishes gradually from utter exhaustion.

The post-mortem examination generally presents that which much surprises the proprietor; one lobe of the gland is very greatly enlarged; it evidently contains fluid. It has under disease become a vast cyst, from which, in a setter, I have actually extracted more than two gallons of serum: from a small spaniel I have taken this organ so increased in size that it positively weighed one half the amount of the body from which it was removed. The wonder is that the apparently weak covering to the liver could bear so great a pressure without bursting.

INDIGESTION

Things must seem to have come to a pretty pass when a book is gravely written upon dyspepsia in dogs. Nevertheless, I am in earnest when I treat upon that subject; and could the animals concerned bear witness, they would testify it was indeed no joke. The Lord Mayor of London does not retire from office with a stomach more deranged than the majority of the canine race, shielded by his worshipful authority, could exhibit. The cause in both instances is the same. Dogs as they increase in years seem to degenerate sadly; till at length they mumble dainties and relish flavors with the gusto of an alderman. Pups even are not worthy of unlimited confidence. The little animals will show much ingenuity in procuring substances that make the belly ache; and, with infantine perversity, will, of their own accord, gobble things which, if administered, would excite shrieks of resistance. A litter of high-bred pups is a source of no less constant annoyance, nor does it require less incessant watching, than a nursery of children. There is so much similarity between man and dog that, from fear of too strongly wounding the self-love of my reader, I must drop the subject.

Indigestion in dogs assumes various forms, and is the source of numerous diseases. Most skin affections may be attributed to it. The inflammation of the gums, the foulness of the teeth, and the offensiveness of the breath, are produced by it. Excessive fatness, with its attendant asthma and hollow cough, are to be directly traced to a disordered digestion. In the long run, half of the petted animals die from diseases originating in this cause; and in nearly every instance the fault lies far more with the weakness of the master than with the corruptness of the beast. He who is invested with authority has more sins, than those he piously acknowledges his own, to answer for.