полная версия

полная версияThe Dog

Acute diarrhœa may terminate in twenty-four hours; the chronic may continue as many days. The first sometimes closes with hemorrhage, blood in large quantities being ejected, either from the mouth or from the anus; but more generally death ensues from apparent exhaustion, which is announced by coldness of the belly and mouth, attended with a peculiar faint and sickly fetor and perfect insensibility. The chronic more rarely, ends with excessive bleeding, but almost always gradually wears out the animal, which for days previous may be paralysed in the hind extremities, lying with its back arched and its feet approximated, though consciousness is retained almost to the last moment. In either case, however, the characteristic stench prevails, and the lower surface of the abdomen, as a general rule, feels hard, presenting to the touch two distinct lines, which run in the course of the spine. These lines, which Youatt mentions as cords, are the recti muscles, which in the dog are composed of continuous fibre, and consequently, when contracted under the stimulus of pain or disease, become very apparent.

On examination after death, the stomach, especially towards the pyloric orifice, is inflamed, as are the intestines, which, however, towards the middle of the track, are less violently affected than at other parts. The cæcum is enlarged, and may even, while all the other guts are empty, contain hard solid fæces. The rectum is generally black with inflammation, and seems most to suffer in these disorders. Occasionally its interior is ulcerated, and such is nearly always its condition towards the anus. Signs of colic are distributed along the entire length of the alimentary tubes.

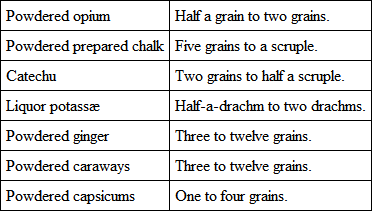

In the acute disease, the case in the first instance should be treated as directed for colic, with turpentine enema and ether, laudanum and water, followed by mild doses of grey powder and ipecacuanha, or chalk, catechu and aromatics, in the proportions directed below: —

This may be given every second hour. The carbonate of ammonia, from two to eight grains, is also deserving of a trial, as are the chlorides and chlorates when the odor is perceived.

Applications, as before directed, to the abdomen are also beneficial; but frequent use of the warm bath should be forbidden, for its action is far too debilitating. The ether, laudanum, and water should be persisted with throughout the treatment, and hope may be indulged so long as the injections are retained; but when these are cast back, or flow out as soon as the pipe is removed, the case may be pronounced a desperate one.

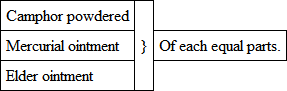

In the chronic form of diarrhœa there is always greater prospect of success. Ether, laudanum, and water will often master it, without the addition of any other medicine; but the liquor potassæ and the chalk preparation are valuable adjuncts. To the anus an ointment will be useful; and it should not only be smeared well over the part, but, by means of a penholder or the little finger, a small quantity should thrice in the course of the day be introduced up the rectum. For this purpose the following will be found to answer much better than any of those which Blaine orders to be employed on similar occasions: —

Cleanliness is of the utmost importance. Thrice daily, or oftener if necessary, the anus and root of the tail should be thoroughly cleansed, with a wash consisting of an ounce of the solution of chloride of zinc to a pint of distilled water. The food should be generous; but fluid beef tea, thickened with rice, will constitute the most proper diet during the existence of diarrhœa.

A little gravy and rice with scraped meat may be gradually introduced; but the dog must be drenched with the liquid rather than indulged with solids at too early a period. All the other measures necessary have been indicated when treating of previous abdominal diseases, and such rules as are therein laid down must, according to the circumstances, be applied.

Peritonitis. – In the acute form this disease is rarely witnessed, save as accompanying or following parturition. Its symptoms are, panting; restlessness; occasional cries; a desire for cold; constant stretching forth at full length upon the side; dry mouth and nose; thirst; constipation; hard quick pulse; catching breathing, and – contrary as it may be to all reasonable expectation – seldom any pain on pressure to the abdomen, toward which, however, the animal constantly inclines the head.

The treatment consists in bleeding from the jugular, from three to twelve ounces being taken; but a pup, not having all its permanent teeth, supposing such an animal could be affected, should not lose more than from half-an-ounce to two ounces. Stimulating applications to the abdomen should be employed, an ammoniacal blister, from its speedy action, being to be preferred. Ether, laudanum, and water ought to be given, to allay the pain, with calomel in small but repeated doses, combined with one-fourth its weight of opium, in order to subdue the inflammation. A turpentine enema to unload the rectum, and a full dose of castor oil to relieve the bowels, should be administered early in the disease. The warm bath, if the animal is after it well wrapped up, may also be resorted to. A second bleeding may be necessary, but it should always be by means of leeches, and should only be practised upon conviction of its necessity, for no animal is less tolerant of blood-letting than the dog.

During peritonitis, the chief aim of all the measures adopted is to reduce the inflammation; but while this is kept in view, it must not be forgotten that of equal, or perhaps of even more, importance, is it to subdue the pain and lessen the constitutional irritation which adds to the energy of the disorder, thus rendering nature the less capable of sustaining it. With this object I have often carried ether, laudanum, and water, so far as to narcotise the animal; and I have kept the dog under the action of these medicines for twelve hours, and then have not entirely relinquished them. The consequence has not always been success, but I have not seen any reason to imagine that the life has not been lengthened by the practice; and sometimes when the narcotism has ceased, the disease has exhibited so marked an improvement, that I have dated the recovery from that period.

Strangulation. – This consists in the intestines being twisted or tied together, and it is caused by sudden emotion or violent exertion. From it the dog is almost exempt, though to it some other animals are much exposed. The symptoms are sudden pain, resembling acute enteritis, accompanied with sickness and constipation, and terminating in the lethargic ease which characterises mortification.

No treatment can save the life, and all the measures justifiable are such as would alleviate the sufferings of the animal; but as, in the majority of these cases, the fact is only ascertained after death, the practitioner must in a great measure be guided by the symptoms.

Introsusception. – This is when a portion of intestine slips into another part of the alimentary tube, and there becomes fixed. Colic always precedes this, for the accident could not occur unless the bowel was in places spasmodically contracted. The symptoms are – colic, in the first instance, speedily followed by enteritis, accompanied by a seeming constipation, that resists all purgatives, and prevails up to the moment of death. The measures would be the same as were alluded to when writing of strangulation.

Stoppage. – To this the dog is much exposed. These animals are taught to run after sticks or stones, and to bring them to their masters. When this trick has been learnt, the creatures are very fond of displaying their accomplishment. They engage in the game with more than pleasure; and as no living being is half so enthusiastic as dogs, they throw their souls into the simple sport. Delighted to please their lords, the animals are in a fever of excitement; they back and run about – their eyes on fire, and every muscle of their frames in motion. The stone is flung, and away goes the dog at its topmost speed, so happy that it has lost its self-command. If the missile should be small, the poor animal, in its eagerness to seize, may unfortunately swallow it, and when that happens, the faithful brute nearly always dies. The œsophagus or gullet of the dog is larger than its intestines, and consequently the substance which can pass down the throat may in the guts become impacted. Such too frequently follows when stones are gulped; for hard things of this kind, though they should be small enough to pass through the alimentary tube, nevertheless would cause a stoppage; for a foreign body of any size, by irritating the intestine, would provoke it to contract, or induce spasm; and the bowel thus excited would close upon the substance, retaining it with a force which could not be overcome. Persons, therefore, who like their dogs to fetch and carry, should never use for this purpose any pebble so small as to be dangerous, or rather, they should never use stones of any kind for this purpose. The animal taught to indulge in this amusement seriously injures its teeth, which during the excitement are employed with imprudent violence, and the mouth sustains more injury than the game can recompense.

If a dog should swallow a stone, let the animal be immediately fed largely; half-an-hour afterwards let thrice the ordinary dose of antimonial wine be administered, and the animal directly afterwards be exercised. Probably the pebble may be returned with the food when the emetic acts. Should such not be the case, as the dog will not eat again, all the thick gruel it can be made to swallow must be forced upon it, and perhaps the stone may come away when this is vomited. Every effort must be used to cause the substance to be ejected before it has reached the bowels, since if it enters these, the doom is sealed. However, should such be the case, the most violent and potent antispasmodics may be tried; and under their influence I have known comparatively large bodies to pass. No attempt must be made to quicken the passage by moulding or kneading the belly; much less must any effort be used intended to push the substance onward. The convolutions of the alimentary track are numerous, and the bowels are not stationary; therefore we have no certainty, even if the violence should do no injury, that our interference would be properly directed. Hope must depend upon antispasmodics; while every measure is taken to anticipate the irritation which is almost certain to follow.

Stoppage may be caused by other things besides stones. Corks, pins, nails, skewers, sharp pieces of bone, particularly portions of game and poultry bones, have produced death; and this fact will serve to enforce the warning which was given in the earlier portion of this work.

PARALYSIS OF THE HIND EXTREMITIES

It appears odd to speak of such an affliction as loss of all motor power in the hind extremities, connected with deranged bowels. What can the stomach have to do with the legs? Why, all and everything. That which is put into the stomach, nourishes the legs, and that which enters the same receptacle, may surely disease the like parts. That which nurtures health, and that which generates sickness, are more closely allied than we are willing to allow. Thus, a moderate meal nourishes and refreshes; but the same food taken in too great abundance, as surely will bring disease; and it is of too much food that I have to complain, when I speak of the bowels as associated with paralysis. Dogs will become great gluttons. They like to do what they see their master doing; but as a dog's repast comes round but once a day, and a human being eats three or four times in the twenty-four hours, so has the animal kept within doors so many additional opportunities of over-gorging itself. Nor is this all. The canine appetite is soon satisfied; the meal is soon devoured. But it is far otherwise with the human repast. The dog may consume enough provender in a few minutes to last till the following day comes round; whereas the man cannot get through the food which is to support him for six hours, in less than half a division of the time here enumerated. Supposing one or two persons to be seated at table, it is very hard to withstand a pair of large, eloquent, and imploring eyes, watching every mouthful the fork lifts from the plate. For a minute or two it may be borne; but to hold out an entire hour is more than human fortitude is capable of. A bit is thrown to the poor dog that looks so very hungry; it is eaten quickly, and then the eyes are at work again. Perhaps the other end of the board is tried, and the appeal is enforced with the supplicatory whine that seldom fails. Piece after piece is thereby extracted; and dogs fed in this fashion will eat much more than if the whole were placed before them at one time. The animal becomes enormously fat, and then one day is found by the mistress with its legs dragging after it. The lady inquires which of the servants have been squeezing the dog in the door. All deny that they have been so amusing themselves, and every one protests that she had not heard poor Fanny cry. The mistress' wrath is by no means allayed. Servants are so careless – such abominable liars – and the poor dog was no favorite down stairs. Thereupon Fanny is wrapped in a couple of shawls, and despatched to the nearest veterinary surgeon.

If the gentleman who may be consulted knows his business, he returns for answer, "The dog is too fat," and must for the future be fed more sparingly – that it has been squeezed in no door – that none of the vertebræ are injured, but the animal is suffering from an attack of paralysis. He sends some physic to be given, and some embrocation to rub on the back. The mistress is by no means satisfied. She protests the man's a fool – declares she alone knows the truth – but, despite her knowledge, does as the veterinary surgeon ordered. Under the treatment the dog recovers; after which every one feeds it, and everybody accuses the other of doing that which the doctor said was not to be done. At length the animal has a second visitation, which is more slowly removed than was the first; but it at last yields; till the third attack comes, with which the poor beast is generally destroyed as incurable.

These dogs, when brought to us, usually appear easy and well to do in the world. The coats are sleek; their eyes are placid; and the extremities alone want motion, which rather seems to surprise the animal than to occasion it any immediate suffering. They have no other obvious disease; but the malignity of their ailments seems fixed or concentrated on the affection which is present. The first attack is soon conquered. A few cathartic pills, followed by castor-oil, prepared as recommended in this work (page 116), will soon unload the bowels, and clear out the digestive canal. They must be continued until, and after, the paralysis has departed. At the same time, some stimulating embrocation must be employed to the back, belly, and hind-legs, which must be well rubbed with it four times daily, or the oftener the better. Soap liniment, as used by Veterinarians, rendered more stimulating by an additional quantity of liquor ammoniæ, will answer very well; more good being done by the friction than by the agent employed. The chief benefit sought by the rubbing, is to restore the circulation, and so bring back feeling with motion, for both are lost; a pin run into the legs produces no effort to retract the limb, nor any sign of pain.

The cure is certain, – and so is the second attack, if the feeding be persisted in; unless nature seeks and finds relief in skin disease, canker, piles, or one of the many consequences induced by over-feeding. The second attack mostly yields to treatment. The third is less certain, and so is each following visitation; the chances of restoration being remote, just in proportion as the assault is removed from the original affliction.

DISEASES ATTENDANT ON DISORDERED BOWELS

RHEUMATISM

It appears almost laughable to talk about a rheumatic dog; but, in fact, the animal suffers quite as, or even more acutely than the human patient, and both from the same cause – over-indulgence; still with this difference – the man usually suffers from attachment to the bottle; the dog endures its misery from devotion to roaming under the table. It is not an uncommon sight to behold an animal so fat that it can hardly waddle, without scruple enjoying its five meals a day; which it takes with a bloated mistress, who, according to her own account, is kept alive with the utmost difficulty by eating little and often. The dog, I say, looks for its lady's tray with regularity, besides having its own personal meal, and a bone or two to indulge any odd craving between whiles. These spoiled animals are, for the most part, old and bad tempered. They would bite, but they have no teeth, and yet they will wrathfully mumble the hand they are unable to injure; while the doting mistress, in alarm for her favorite, sits upon the sofa entreating the beast may not be hurt: begging for pity, as though it were for her own life she were pleading. The animal during this is being followed from under table to chair, growling and barking all the time; and showing every disposition, if it had but ability, to do you some grievous bodily harm. At length, after a chase that has nearly caused the fond mistress to faint and you to exhaust all patience, the poor brute is overtaken and caught; but no sooner does your hand touch the miserable beast, than it sets up a howl fit to alarm the neighborhood. On this the hand is moved from the neck to the belly, intending to raise the dog from the ground; but the howl thereon is changed to a positive scream, when the mistress starts up, declaring she can bear no more. On this you desist, to ask a few questions: "The dog has often called out in that manner?" "O yes." "And has done so, no one being near or touching it?" "O yes, when quite alone." Thereupon you request the mistress to call the animal to her; and it waddles across the carpet, every member stiff, its back arched, and its neck set, but the eye fixed upon the person who has been called in.

You get the mistress to take the favorite upon her lap, and request she will oblige you by pinching the skin. "Oh, harder; pray, a little harder, madam!" Nevertheless, all your entreaties cannot move the kind mistress to do that which she fears will pain her pet; whereon you request permission to be permitted to make a trial; and it being granted, you seize the coat, and give the animal one of the hardest pinches of which your fore-finger and thumb, compressed with all your might, are capable. The animal turns its head round and licks your hand, to reward the polite attention, and solicits a continuance of your favors. The skin is thick and insensible. What teeth remain, are covered with tartar, and the breath smells like a pestilence.

The dog is taken home, and an allowance of wholesome rice and gravy placed before it, with one ounce of meat by weight. The flesh is greedily devoured, but the other mess remains untouched. The next day the untouched portion is removed, and fresh supplied; also the same meat as before, which is consumed ere the hand which presented the morsel is retracted, the head being raised to ask for more.

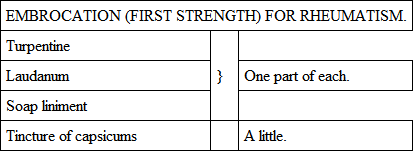

The second day, however, the gravy and rice are eaten, and the meat on the morrow is deficient; gravy and rice for the future constituting the animal's fare. Then, for physic, an embrocation containing one-third of turpentine is used thrice daily, to rub the animal's back, neck, and belly with. Some of the cathartic pills are given over night, with the castor-oil mixture in the morning. Constant purgation is judiciously kept up, and before the first fortnight expires, the dog ceases to howl. Then the pills and mixture are given every other night, and the quantity of turpentine in the embrocation increased to one-half, the other ingredients being of the same amount. This rubbed in as before, evidently annoys the animal, and on that account is used only twice a-day. When all signs of pain are gone, the turpentine is then lowered to one-third, the embrocation being applied only once a-day, because it now gives actual pain. Some liniment, however, is continued, generally making the poor beast howl whenever it is administered. At the expiration of a month, all treatment is abandoned for a week, that the skin may get rid of its scurf, and you may perceive the effect of the treatment you have pursued. If the skin then appears thin, especially on the neck and near the tail, being also sensitive, clean the teeth, and send the dog home with a bottle of cleansing fluid, a tooth-brush, (as before explained,) and strict injunctions with regard to diet.

The subsequent strength is made by increasing the quantity of turpentine.

THE RECTUM

Piles. – The dog is very subject to these annoyances in all their various forms; for the posterior intestine of the animal seems to be peculiarly susceptible of disease. When enteritis exists the rectum never escapes, but is very frequently the seat of the most virulent malice of the disorder. There are reasons why such should be the case. The dog has but a small apology for what should be a cæcum, and the colon I assume to be entirely wanting. The guts, which in the horse are largest, in the canine species are not characterised by any difference of bulk; and however compact may be the food on which the dog subsists, nevertheless a proportionate quantity of its substance must be voided. If the excrement be less than in beasts of herbivorous natures, yet there being but one small receptacle in which it can be retained, the effects upon that receptacle are more concentrated, and the consequences therefore are very much more violent. The dung of the horse and ox is naturally moist, and only during disease is it ever in a contrary condition. Costiveness is nearly always in some degree present in the dog. During health the animal's bowels are never relaxed; but the violent straining it habitually employs to expel its fæces would alone suggest the injury to which the rectum is exposed, even if the inclination to swallow substances which in their passage are likely to cause excoriation did not exist. The grit, dirt, bone, and filth that dogs will, spite of every precaution, manage to obtain, must be frequent sources of piles, which without such instigation would frequently appear. Bones, which people carelessly conclude the dog should consume, it can in some measure digest; but it can do this only partially when in vigorous health. Should the body be delicate, such substances pass through it hardly affected by the powers of assimilation; they become sharp and hard projections when surrounded by, and fixed in the firm mass, which is characteristic of the excrement of the dog. A pointed piece of bone, projecting from an almost solid body, is nearly certain to lacerate the tender and soft membrane over which it would have to be propelled; and though, as I have said, strong and vigorous dogs can eat almost with impunity, and extract considerable nourishment from bones, nevertheless they do not constitute a proper food for these animals at any time. When the system is debilitated, the digestion is always feeble; and, under some conditions of disease, I have taken from the stomachs of dogs after death, in an unaltered state, meat, which had been swallowed two days prior to death. It had been eaten and had been retained for at least forty-eight hours, but all the functions had been paralyzed, and it continued unchanged. If such a thing be possible under any circumstances, then in the fact there is sufficient reason why people should be more cautious in the mode of feeding these creatures; for I have extracted from the rectums of dogs large quantities of trash, such as hardened masses of comminuted bones and of cocoanut, which, because the animal would eat it, the owners thought it to be incapable of doing harm. Nature has not fitted the dog to thrive upon many substances; certain vegetables afford it wholesome nourishment, but a large share of that which is either wantonly or ignorantly given as food, is neither nutritive nor harmless. Whatever injures the digestion, from the disposition of the rectum to sympathise in all disorders of the great mucous track, is likely to induce piles; and the anus of the animal is often as indicative of the general state of the body as is the tongue of man.