полная версия

полная версияThe Dog

I cannot close my account of distemper without cautioning the reader against the too long use of quinine. It is a most valuable medicine, and, as a general rule, no less safe than useful. I do not know that it can act as a poison, or destroy the life; but it can produce evils hardly less, and more difficult to cure, than those it was employed to eradicate. The most certain and most potent febrifuge, and the most active tonic, it can also induce blindness and deafness; and by the too long or too large employment of quinine a fever is induced, which hangs upon the dog, and keeps him thin for many a month. Therefore, when the more violent stages of the disease have been conquered, it should no longer be employed. Other tonics will then do quite as well, and a change of medicine often performs that which no one, if persevered with, will accomplish.

All writers, when treating of distemper, speak of worms, and give directions for their removal during the existence of the disease. I know they are too often present, and I am afraid they too often aggravate the symptoms; but it is no easy matter to judge precisely when they do or when they do not exist. The remedies most to be depended upon for their destruction, are not such as can be beneficial to the animal laboring under this disorder; but, on the other hand, the tonic course of treatment I propose is very likely to be destructive to the worms. Therefore, rather than risk the possibility of doing harm, I rely upon the tonics, and have no reason to repent the confidence evinced in this particular.

The treatment of distemper consists in avoiding all and everything which can debilitate; it is, simply, strengthening by medicine aided by good nursing. It is neither mysterious nor complex, but is both clear and simple when once understood. It was ignorance alone which induced men to resort to filth and cruelty for the relief of that which is not difficult to cure. In animals, I am certain, kindness is ninety-nine parts of what passes for wisdom; and, in man, I do not think the proportion is much less; for how often does the mother's love preserve the life which science abandons! To dogs we may be a little experimental; and with these creatures, therefore, there is no objection to trying the effects of those gentler feelings, which the very philosophical sneer at as the indications of weakness. When I am called to see a dog, if there be a lady for its nurse, I am always more certain as to the result; for the medicines I send then seem to have twice the effect.

MOUTH, TEETH, TONGUE, GULLET, ETC

The mouth of the dog is not subject to many diseases; but it sometimes occasions misery to the animal. Much of such suffering is consequent upon the folly and thoughtlessness of people, who, having power given them over life, act as though the highest gift of God could be rendered secondary to the momentary pleasure of man. No matter in what form vitality may appear – for itself it is sacred; it has claims and rights, which it is equally idle and ridiculous to deny or to dispute. The law of the land may declare and make man to have a possession in a beast; but no act of parliament ever yet enacted has placed health and life among human property. The body may be the master's; but the spirit that supports and animates it is reserved to another. Disease and death will resent torture, and rescue the afflicted; he who undertakes the custody of an animal is morally and religiously answerable for its happiness. To make happy becomes then a duty; and to care for the welfare is an obligation. Too little is thought of this; and the fact is not yet credited. The gentleman will sport with the agony of animals; and to speak of consideration for the brute, is regarded either as an eccentricity or an affectation. This is the case generally at the present time; and it is strange it should be so, since Providence, from the creation of the earth, has been striving to woo and to teach us to entertain gentler sentiments. No one ever played with cruelty but he lost by the game, and still the sport is fashionable. No one ever spared or relieved the meanest creature but in his feelings he was rewarded; and yet are there comparatively few who will seek such pleasure. Neither through our sensibilities nor our interests are we quick to learn that which Heaven itself is constantly striving to impress.

The dog is our companion, our servant, and our friend. With more than matrimonial faith does the honorable beast wed itself to man. In sickness and in health, literally does it obey, serve, love, and honor. Absolutely does it cleave only unto one, forsaking all others – for even from its own species does it separate itself, devoting its heart to man. In the very spirit and to the letter of the contract does it yield itself, accepting its life's load for better, for worse – for richer, for poorer – in sickness and in health – to love, cherish, and to obey till death. The name of the animal may be a reproach, but the affection of the dog realizes the ideal of conjugal fidelity. Nevertheless, with all its estimable qualities, it is despised, and we know not how to prize, or in what way to treat it. It is the inmate of our homes, and the associate of our leisure: and yet its requirements are not recognised, nor its necessities appreciated. Its docility and intelligence are employed to undermine its health; and its willingness to learn and to obey is converted into a reason for destroying its constitution. What it can do we are content to assume it was intended to perform; and that which it will eat we are satisfied to assert was destined to be its food.

Bones, stones, and bricks, are not beneficial to dogs. The animals may be tutored to carry the two last, and impelled by hunger they will eat the first. Hard substances and heavy weights, however, when firmly grasped, of course wear the teeth; and the organs of mastication are even more valuable to the meanest cur than to the wealthiest dame. If the mouth of the human being be toothless, the cook can be told to provide for the occasion, or the dentist will in a great measure supply the loss. But the toothless dog must eat its customary food; and it must do this, although the last stump or remaining fang be excoriating the lips, and ulcerating the gums. The ability to crush, and the power to digest bones, is thought to be a proof that dogs were made to thrive upon such diet; and Blaine speaks of a meal of bones as a wholesome canine dish. I beg the owners of dogs not to be led away by so unfounded an opinion. A bone to a dog is a treat, and one which should not be denied; but it should come in only as a kind of dessert after a hearty meal. Then the creature will not strain to break and strive to swallow it; but it will amuse itself picking off little bits, and at the same time benefit itself by cleaning its teeth. Much more ingenuity than force will be employed, and the mouth will not be injured. In a state of nature this would be the regular course. The dog when wild hunts its prey; and, having caught, proceeds to feast upon the flesh, which it tears off; this, being soft, does not severely tax the masticating members. When the stomach is filled, the skeleton may be polished; but hungry dogs never take to bones when there is a choice of meat. It is a mistaken charity which throws a bone to a starving hound.

Equally injurious to the teeth, are luxuries which disorder the digestion. High breeding likewise will render the mouth toothless at a very early age; but of all things the very worst is salivation, which, by the ignorant people who undertake to cure the diseases of these sensitive and delicate animals, is often induced though seldom recognised, and if recognised, always left to take its course.

The mouth of the dog is therefore exposed to several evils; and there are not many of these animals which retain their teeth even at the middle age. High-bred spaniels are the soonest toothless; hard or luxurious feeding rapidly makes bare the gums. Stones, bones, &c., wear down the teeth; but the stumps become sources of irritation, and often cause disease. Salivation may, according to its violence, either remove all the teeth, or discolor any that may be retained. The hale dog's teeth, if properly cared for, will generally last during the creature's life; and continue white almost to the remotest period of its existence. I have seen very aged animals with beautiful mouths; but such sights, for the reasons which have been pointed out, are unfortunately rare. The teeth of the dog, however, may be perfectly clean and entire even at the twelfth year; and it is no more than folly to pretend that these organs are in any way indicative of the age of this animal. They are of no further importance to a purchaser than as signs which denote the state of the system, and show the uses to which the animal has been subjected. The primary teeth are cut sometimes as early as the third week; but, in the same litter, one pup may not show more than the point of an incisor when it is six weeks old; while another may display all those teeth well up. As a general rule, the permanent incisors begin to come up about the fourth month; but I have known a dog to be ten months old, and, nevertheless, to have all the temporary teeth in its head. The deviations, consequently, are so great that no rule can be laid down; and every person who pretends to judge of the dog's age by the teeth is either deceived himself, or practising upon the ignorance of others.

Strong pups require no attention during dentition; but high-bred and weakly animals should be constantly watched during this period. When a tooth is loose, it should be drawn at once, and never suffered to remain a useless source of irritation. If suffered to continue in the mouth, it will ultimately become tightened; and the food or portions of hair getting and lodging between it and the permanent teeth, will inflame the gum, and cause the beast considerable suffering. The extraction at first is so slight an operation, that when undertaken by a person having the proper instruments, and knowing how to use them, the pup does not even vent a single cry. The temporary tusks of small dogs are very commonly retained after the permanent ones are fully up, and if not removed, will remain perhaps during the life; they become firm and fixed, the necks being united to the bone. This is more common in the upper than in the lower jaw, but I have seen it in both. Diminutive high-bred animals rarely shed the primary tusks naturally; therefore, when the incisors have been cut, and the permanent fang teeth begin to make their appearance through the gums, the temporary ones ought, as frequently as possible, to be moved backward and forward with the finger, in order to loosen them. When that is accomplished, they should be extracted, which if not done at this time will afterwards be difficult. As the tooth becomes again fixed, filth of various kinds accumulates between it and the permanent tusk; the animal feeds in pain, the gum swells and ulcerates, and sometimes the permanent tusk falls out, but the cause of the injury never naturally comes away.

To extract a temporary tusk after it has reset is somewhat difficult, and is not to be undertaken by every bungler. The gum must be deeply lanced; and a small scalpel made for the purpose answers better than the ordinary gum lancet. The instrument having been passed all round the neck of the tooth, the gum is with the forceps to be driven or pushed away, and the hold to be taken as high as possible; firm traction is then to be made, the hand of the operator being steadied by the thumb placed against the point of the permanent tusk. As the temporary teeth are almost as brittle as glass, and as the animal invariably moves its head about, endeavoring to escape, some care must be exercised to prevent the tooth being broken. However, if it is thoroughly set, we must not expect to draw it with the fang entire, for that has become absorbed, and the neck is united to the jawbone. The object, therefore, in such cases, is to grasp the tooth as high up as possible, and break it off so that the gum may close over any small remainder of the fang which shall be left in the mouth. The operator, therefore, makes his pull with this intention; and when the tooth gives way, he feels, to discover if his object has been accomplished. Should any projecting portion of tooth, or little point of dislodged bone be felt, these must be removed; and in less than a day the wound shows a disposition to heal; but it should afterwards be inspected occasionally, in case of accidents.

When foulness of the mouth is the consequence of the system of breeding, the constitution must be invigorated by the employment of such medicines as the symptoms indicate: and the teeth no further interfered with than may be required either for the health, ease, or cleanliness of the animal.

From age, improper food, and disease conjoined, the dog's mouth is frequently a torture to the beast, and a nuisance to all about it. The teeth grow black from an incrustation of tartar; the insides of the lips ulcerate; the gums bleed at the slightest touch, and the breath stinks most intolerably. The dog will not eat, and sometimes is afraid even to drink; the throat is sore, and saliva dribbles from the mouth; the animal loses flesh, and is a picture of misery.

When such is the case, the cure must be undertaken with all regard to the dog's condition; harm only will follow brutality or haste. The animal must be humored, and the business must be got through little by little. In some very bad cases of this description I have had no less than three visits before my patient was entirely cleansed. At the first sitting I examine the mouth, and with a small probe seek for every remnant of a stump, trying the firmness of every remaining tooth. All that are quite loose are extracted first, and then the stumps are drawn, the gums being lanced where it is necessary. This over, I employ a weak solution of the chloride of zinc – a grain to an ounce of sweetened water – as a lotion, and send the dog home, ordering the mouth, gums, teeth, and lips to be well washed with it, at least three times in the course of a day. In four days the animal is brought to me again, and then I scale the teeth with instruments similar to those employed by the human dentist, only of a small size. The dog resists this operation more stoutly than it generally does the extraction, and patience is imperative. The operation will be the more quickly got over by taking time, and exerting firmness without severity. A loud word or a box on the ear may on some occasions be required; but on no account should a blow he given, or anything done to provoke the anger of the animal. The mistress or master should never be present; for the cunning brute will take advantage of their fondness, and sham so artfully that it will be useless to attempt to proceed.

I usually have no assistance, but carry the dog into a room by itself; and having spoken to it, or taken such little liberties as denote my authority, I commence the more serious part of the business. Amidst remonstrance and expostulation, caresses and scolding, the work then is got over; but seldom so thoroughly that a little further attention is not needed, which is given on the following day.

The incrustation on the dog's teeth, more especially on the fangs, is often very thick. It is best removed by getting the instrument between the substance and the gum; then with a kind of wrenching action snapping it away, when frequently it will shell off in large flakes; the remaining portions should be scraped, and the tooth should afterwards look white, or nearly so. The instrument may be used without any fear of injuring the enamel, which is so hard that steel can make no impression on it; but there is always danger of hurting the gums, and as the resistance of the dog increases this, the practitioner must exert himself to guard against it. Some precaution also will be necessary to thwart occasional attempts to bite; but a little practice will give all the needful protection, and those who are not accustomed to such operations will best save themselves by not hitting the dog; for the teeth are almost certain to mark the hand that strikes. Firmness will gain submission; cruelty will only get up a quarrel, in which the dog will conquer, and the man, even if he prove victorious, can win nothing. He who is cleaning canine teeth must not expect to earn the love of his patient; the liberty taken is so great that it is never afterwards pardoned. I scarcely ever yet have known the dog to which I was not subsequently an object of dread and hatred. Grateful and intelligent as these creatures are, I have not found one simple or noble-minded enough to appreciate a dentist.

The only direction I have to add to the above, concerns the means necessary to guard against a relapse, and to afford general relief to the constitution. To effect the first object, prepare a weak solution of chloride of zinc – one grain to the ounce – and flavor the liquid with oil of aniseed. This give to your employer, together with a small stencilling, or poonah painting brush, which is a stiff brush used in certain mechanical pursuits of art; desire him to saturate the brush in the liquid, and with it to clean the dog's teeth every morning; which, if done as directed, will prevent fresh tartar accumulating, and in time remove any portion that may have escaped the eye of the operator, sweetening the animal's breath. With regard to that medicine the constitution may require, it is impossible to say what the different kinds of dogs affected may necessitate – none can be named here; the symptoms must be observed, and according to these should be the treatment; which must be studied from the principles inculcated throughout this work. Most usually, however, tonics, stimulants, and alteratives will be required, and their operation will be gratifying. The dog, which before was offensive and miserable, may speedily become comfortable and happy; and should the errors which induced its misfortune be afterwards avoided, it may continue to enjoy its brief life up to the latest moment; therefore the teeth should never be neglected; but if any further reason be required to enforce the necessity of attending to the mouth, surely it might be found in the frightful disease to which it is occasionally subject.

When the teeth, either by decay or from excessive wear, have been reduced to mere stumps, their vitality often is lost. They then act as foreign bodies, and inflame the parts adjacent to them. Should that inflammation not be attended to, it extends, first involving the bones of the lower jaw, and afterwards the gums, and canker of the mouth is established.

Such is the course of the disease, the symptoms of which are redness and swelling during the commencement. Suppuration from time to time appears; but as the animal with its tongue removes the pus, this last effect may not be observed. The enlargement increases, till at last a hard body seems to be formed on the jaw, immediately beneath the skin. The surface of the gums may be tender, and bleed on being touched, but the tumor itself is not painful when it first appears, and throughout its course is not highly sensitive. At length it discharges a thin fluid, which is sometimes mingled with pus, and generally with more or less blood. The stench which ultimately is given off becomes powerful; and a mass of proud flesh grows upon the part, while sinuses form in various directions. Hemorrhage now is frequent and profuse, and we have to deal with a cancerous affection, which probably it may not be in our power to alleviate. The dog, which does not appear to suffer, by its actions encourages the belief that it endures no acute pain – and for a length of time maintains its condition; but, in the end, the flesh wastes and the strength gives way; the sore enlarges, and the animal may die of any disease to which its state predisposes it to be attacked.

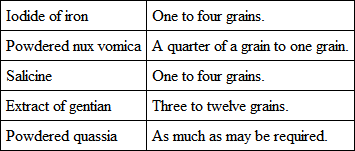

The treatment consists in searching for any stump or portion of tooth that may be retained. All such must be extracted, and also all the molars on the diseased side, without any regard to the few which may be left in the jaw. This done, the constitution must be strengthened, and pills, as directed, with the liquor arsenicalis, should be employed for that purpose.

The above forms one pill, three or four of which should be given daily, with any other medicine which the case may require.

To the part itself a weak solution of the chloride of zinc may be used; but nothing further should be done until the system has been invigorated, and the health, as far as possible, restored. That being accomplished, if the tumor is still perfect, it should be cut down upon and removed. If any part of the bone is diseased, so much should be taken away as will leave a healthy surface.

However, before the dog is brought to the veterinary surgeon for treatment, very often the tumor has lost its integrity, and there is a running sore to be healed. To this probably some ignorant persons have been applying caustics and erodents, which have done much harm, and caused it to increase. In such a case we strengthen the constitution by all possible means, and to the part order fomentations of a decoction of poppy-heads, containing chloride of zinc in minute quantities. Other anodyne applications may also be employed; the object being to allay any existing irritation, for the chloride is merely added to correct the fetor, which at this period is never absent. After some days we strive to ascertain what action the internal remedies have had upon the cancer; for by this circumstance the surgeon will decide whether he is justified in hazarding an operation. If the health has improved, but simultaneously the affected part has become worse, then the inference is unfavorable; for the disease is no longer to be regarded as local. The constitution is involved, and an operation would produce no benefit, but hasten the death, while it added to the suffering of the beast. The growth would be reproduced, and its effects would be more violent; consequently nothing further can be done beyond supporting the system, and alleviating any torture the animal may endure. But if the body has improved, and the tumor has remained stationary, or is suspected to be a little better, the knife may be resorted to; although the chance of cure is rather against success. The age of the animal, and the predisposition to throw out tumors of this nature, are against the result; for too frequently, after the jaw has healed, some distant part is attacked with a disease of a similar character.

Worming, as it is generally called, is often-practised upon dogs, and both Blaine and Youatt give directions for its performance. I shall not follow their examples. It is a needless, and therefore a cruel operation; and though often requested to do so, I never will worm a dog. Several persons, some high in rank, have been offended by my refusal; but my profession has obligations which may not be infringed for the gratification of individuals. People who talk of a worm in the tongue of a dog, only show their ignorance, and by requesting it should be removed, expose their want of feeling.

Pups, when about half-grown, are sometimes seized with an inclination to destroy all kinds of property. Ladies are often vexed by discovering the havoc which their little favorites have made with articles of millinery; gloves, shawls, and bonnets, are pulled to pieces with a seeming zest for mischief, and the culprit is found wagging its tail for joy among the wreck it has occasioned. Great distress is created by this propensity, and a means to check it is naturally sought for. Mangling the tongue will not have the desired effect. For a few days pain may make the animal disinclined to use its mouth; but when this ceases, the teeth will be employed as ingeniously as before. Some good is accomplished by clipping the temporary fangs: these are very brittle, and easily cut through. The excision causes no pain, but the point being gone, the dog's pleasure is destroyed; and, as these teeth will naturally be soon shed, no injury of any consequence is inflicted. By such a simple measure, more benefit than worming ever produced is secured; for in the last case, almost in every instance, the obnoxious habit entirely ceases.

As to worming being of any, even the slightest, protection, in case rabies should attack the dog, the idea is so preposterous, that I shall not here stay to notice it.