полная версия

полная версияThe Dog

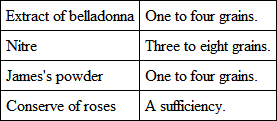

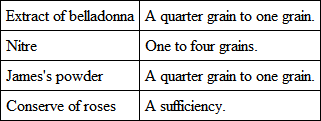

This will be the quantity for one pill; but a better effect is produced if the medicine be administered in smaller doses, and at shorter intervals. If the dog can be constantly attended to, and does not resist the exhibition of pills, or will swallow them readily when concealed in a bit of meat, the following may be given every hour: —

With these a very little of the tincture of aconite may be also blended, not more than one drop to four pills. The tonics ought during the time to be discontinued, and the chest should be daily auscultated to learn when the symptoms subside. So soon as a marked change is observed, the tonic treatment must be resumed, nor need we wait until all signs of chest affection have disappeared. When the more active stage is mastered by strengthening the system, the cure is often hastened; but the animal should be watched, as sometimes the affection will return. More frequently, however, while the lungs engross attention, the eyes become disordered. When such is the case, the tonics may be at once resorted to; for then there is little fear but the disease is leaving the chest to involve other structures.

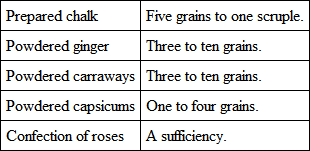

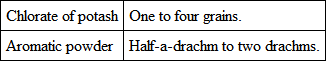

Diarrhœa may next start up. If it appears, let ether and laudanum be immediately administered, both by the mouth and by injection. To one pint of gruel add two ounces of sulphuric ether, and four scruples of the tincture of opium; shake them well together. From half an ounce to a quarter of a pint of this may be employed as an enema, which should be administered with great gentleness, as the desire is that it should be retained. This should be repeated every third hour, or oftener if the symptoms seem urgent, and there is much straining after the motions. From a tablespoonful to four times that quantity of the ether and laudanum mixture, in a small quantity of simple syrup, may be given every second hour by the mouth; but if there is any indication of colic, the dose may be repeated every hour or half hour; and I have occasionally given a second dose when only ten minutes have elapsed. Should the purgation continue, and the pain subside, from five to twenty drops of liquor potassæ may be added to every dose of ether given by the mouth; which, when there is no colic, should be once in three hours, and the pills directed below may be exhibited at the same time: —

To the foregoing, from two to eight grains of powdered catechu may be added should it seem to be required, but it is not generally needed. Opium more than has been recommended, in this stage, is not usually beneficial; and, save in conjunction with ether, which appears to deprive it of its injurious property, I am not in the habit of employing it.

I have been more full in my directions for diarrhœa than was perhaps required by the majority of cases. Under the administration of the ether only I am, therefore, never in a hurry to resort even to the liquor potassæ, which, however, I use some time before I employ the astringent pills, and during the whole period I persevere with the tonic. The diet I restrict to strong beef tea, thickened with ground rice, and nothing of a solid nature is allowed. Should these measures not arrest the purgation, but the fæces become offensive, chloride of zinc is introduced into the injection, and also into the ether given by the mouth. With the first, from a teaspoonful to a tablespoonful of the solution is combined, and with the last half those quantities is blended. A wash, composed of two ounces of the solution of the chloride to a pint of cold water, is also made use of to cleanse the anus, about which, and the root of the tail, the fæces have a tendency to accumulate. Warm turpentine I have sometimes with advantage had repeatedly held to the abdomen, by means of flannels heated and then dipt into the oil, which is afterwards wrung out. This, however, is apt to be energetic in its action; but that circumstance offers no objection to its employment. When it causes much pain, it may be discontinued, and with the less regret, as the necessity is the less in proportion as the sensibility is the greater. Should it even produce no indication of uneasiness, it must nevertheless not be carried too far, since on the dog it will cause serious irritation if injudiciously employed; and we may then have the consequences of the application to contend with added to the effects of the disease. When it produces violent irritation, a wash made of a drachm of the carbonate of ammonia to half a pint of water may be applied to the surface; and when the inflammation subsides, the part may be dressed with spermaceti ointment. The fits are more to be dreaded than any other symptom; when fairly established, they are seldom mastered. I have no occasion to boast of the success of my treatment of these fits. All I can advance in favor of my practice is, that it does sometimes save the life, and certainly alleviates the sufferings of the patient; while of that plan of treatment which is generally recommended and pursued, I can confidently assert it always destroys, adding torture to the pains of death. In my hands not more than one in ten are relieved, but when I followed the custom of Blaine none ever lived, – the fate was sealed, and its horrors were increased by the folly and ignorance of him who was employed to watch over, and was supposed to be able to control. Let the owners of dogs, when these animals have true distemper fits, rather cut short their lives than allow the creatures to be tampered with for no earthly prospect. I have no hesitation when saying this; the doom of the dog with distemper fits may be regarded as sealed; and medicine, which will seldom save, should be studied chiefly as a means of lessening the last agonies. In this light alone can I recommend the practice I am in the habit of adopting. When under it any animal recovers, the result is rather to be attributed to the powers of nature than to be ascribed to the virtues of medicine; which by the frequency of its failure shows that its potency is subservient to many circumstances. Blaine and Youatt, both by the terms in which they speak of, and the directions they lay down for, the cure of distemper fits, evidently did not understand the pathology of this form of the disease. These authors seem to argue that the fits are a separate disease, and not the symptoms only of an existing disorder. The treatment they order is depletive, whereas, the attacks appearing only after the distemper has exhausted the strength, a little reflection convinces us the fits are the results of weakness. Their views are mistaken, and their remedies are prejudicial. They speak of distemper being sometimes ushered in by a fit, and their language implies that the convulsions, sometimes seen at the first period, are identical with those witnessed only during the latest stages. This is not the fact. A fit may be observed before the appearance of the distemper; and anything which, like a fit, shows the system to be deranged, may predispose the animal to be affected; but, between fits of any kind, and the termination of the affection in relation to distemper, there is no reason to imagine there is an absolute connexion. The true distemper fit is never observed early – at least, I have never beheld it – before the expiration of the third week; and I am happy in being able to add, that when my directions have from the first been followed, I have never known an instance in which the fits have started up. Therefore, if seldom to be cured, I have cause to think they may be generally prevented.

When the symptoms denote the probable appearance of fits, although the appetite should be craving, the food must be light and spare. At the Veterinary College, the pupils are taught that the increase of the appetite at this particular period is a benevolent provision to strengthen the body for the approaching trial. Nature, foreseeing the struggle her creature is doomed to undergo – the teacher used to say – gives a desire for food, that the body may have vigor to endure it; and the young gentlemen are advised, therefore, to gratify the cravings of the dog. This is sad nonsense, which pretends to comprehend those motives that are far beyond mortal recognition. We cannot read the intentions of every human mind, and it displays presumption when we pretend to understand the designs of Providence. There are subjects upon which prudence would enjoin silence. The voracity is excessive, but it is a morbid prompting. When the fits are threatened, the stomach is either acutely inflamed, or in places actually sore, the cuticle being removed, and the surface raw. After a full meal at such a period, a fit may follow, or continuous cries may evidence the pain which it inflicts. Nothing solid should be allowed; the strongest animal jelly, in which arrowroot or ground rice is mixed, must constitute the diet; and this must be perfectly cold before the dog is permitted to touch it: the quantity may be large, but the amount given at one time must be small. A little pup should have the essence of at least a pound of beef in the course of the day, and a Newfoundland or mastiff would require eight times that weight of nutriment: this should be given little by little, a portion every hour, and nothing more save water must be placed within the animal's reach. The bed must not be hay or straw, nor must any wooden utensil be at hand; for there is a disposition to eat such things. A strong canvas bag, lightly filled with sweet hay, answers the purpose best; but if the slightest inclination to gnaw is observed, a bare floor is preferable. The muzzle does not answer; for it irritates the temper which sickness has rendered sensitive. Therefore no restraint, or as little as is consonant with the circumstances, must be enforced. Emetics are not indicated. Could we know with certainty that the stomach was loaded with foreign matters, necessity would oblige their use; but there can be no knowledge of this fact – and of themselves these agents are at this time most injurious. Purgatives are poisons now. There is always apparent constipation; but it is confined only to the posterior intestine, and is only mechanical. Diarrhœa is certain to commence when the rectum is unloaded, and nothing likely to irritate the intestines is admissible. The fluid food will have all the aperient effect that can be desired. As to setons, they are useless during the active stage; and if continued after it has passed, they annoy and weaken the poor patient: in fact, nothing must be done which has not hitherto been proposed.

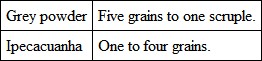

When signs indicative of approaching fits are remarked, small doses of mercury and ipecacuanha should be administered.

Give the above thrice daily; but if it produces sickness, let the quantity at the next dose be one-half.

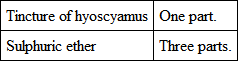

This should be mixed with cold soup, ten ounces of which should be mingled with one ounce of the medicine. Give an ounce every hour to a small dog, and four ounces to the largest animal. A full enema of the solution of soap should be thrown up; and the rectum having been emptied, an ounce or four ounces of the sulphuric ether and hyoscyamus mixture ought to be injected every hour. Over the anterior part of the forehead, from one to four leeches may be applied. To do this the hair must be cut close, and the parts shaved; then, with a pair of scissors, the skin must be snipped through, and the leech put to the wound: after tasting the blood it will take hold. To the nape of the neck a small blister may be applied; and if it rises, the hope will mount with it. A blister is altogether preferable to a seton; the one acts as a derivative, by drawing the blood immediately to the surface without producing absolute inflammation, which the other as a foreign body violently excites. The effects of vesicants are speedy, those of setons are remote; and I have seen fearful spectacles induced by their employment. With dogs setons are never safe; for these animals, with their teeth or claws, are nearly certain to tear them out. In cases of fits, if the seton causes much discharge, it is debilitating and also offensive to the dog, and the ends of the tape are to him an incessant annoyance. It is not my practice to employ setons, being convinced that those agents are not beneficial to the canine race; but to blisters, which on these animals are seldom used, I have little objection. With the ammonia and cantharides, turpentine and mustard, we have so much variety, both as to strength and speed of action, that we can suit the remedy to the circumstances, which, in the instance of a creature so sensitive and irritable as the dog, is of all importance. The blister which I employ in distemper fits is composed of equal parts of liquor ammoniæ and camphorated spirits. I saturate a piece of sponge or piline with this compound; and having removed the hair, I apply it to the nape of the neck, where it is retained from five to fifteen minutes, according to the effect it appears to produce. Great relief is often obtained by this practice; and should it be necessary, I sometimes repeat the application a little lower down towards the shoulders, but never on the same place; for even though no apparent rubefaction may be discerned, the deeper seated structures are apt to be affected, and should the animal survive, serious sloughing may follow, if the blister be repeated too quickly on one part.

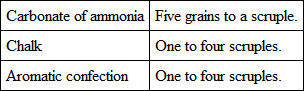

The directions given above apply to that stage when the eye and other symptoms indicate the approach of fits, or when the champing has commenced. The tonic pills and liquor arsenicalis may also then be continued; but when the fits have positively occurred, other measures must be adopted. If colic should attack the animal, laudanum must be administered, and in small but repeated doses, until the pain is dismissed. Opium is of itself objectionable; but the drug does less injury than does the suffering, and, therefore, we choose between the two evils. From five to twenty drops of the tincture, combined with half-a-drachm to two drachms of sulphuric ether, may be given every half-hour during the paroxysm; and either the dose diminished or the intervals increased as the agony lessens, the animal being at the same time constantly watched. The ethereal enemas should be simultaneously exhibited, and repeated every half-hour. When a fit occurs, nothing should during its existence be given by the mouth, except with the stomach-pump, or by means of a large-sized catheter introduced into the pharynx. Unless this precaution be taken, there is much danger of the fluid being carried into the lungs. Ether by injection, however, is of every service, and where the proper instruments are at hand, it ought also to be given by the mouth. The doses have been described. To the liquor arsenicalis, from half a drop to two drops of the tincture of aconite may with every dose be blended; and the solution of the chloride of lime should be mingled with the injections, as ordered for diarrhœa, which, if not present, is certain to be near at hand. The following may also be exhibited, either as a soft mass or as a fluid mixture: —

Or,

Either of the above may be tried every third hour, but on no account ought the warm bath to be used. An embrocation, as directed for rheumatism, may be employed to the feet and legs, and warm turpentine may, as described in diarrhœa, be used to the abdomen. Cold or evaporating lotions to the head are of service, but unless they can be continuously applied, they do harm. Their action must be prolonged and kept up night and day, or they had better not be employed, as the reaction they provoke is excessive. Cold water dashed upon the head during the fit does no good, but rather seems to produce evil. The shock often aggravates the convulsions; and the wet which soon dries upon the skull is followed by a marked increase of temperature; while, remaining upon other parts, and chilling these, it drives the blood to the head.

From the foregoing, it will have been seen that my efforts are chiefly directed to strengthening the system, and, so far as possible, avoiding anything that might add to the irritability. On these principles I have sometimes succeeded, and most often when the fits have been caused by some foreign substance in the stomach or intestines. When such is the case, the fits are mostly short and frequent. One dog that had one of these attacks, which did not last above forty seconds every five minutes, and was very noisy, lived in pain for two days, and then passed a peach-stone, from which moment it began to recover, and is now alive. In another case, a nail was vomited, and the animal from that time commenced improving. In this instance an emetic would have been of benefit; but such occurrences are rare, and the emetic does not, even when required, do the same good as is produced by the natural ejection of the offending agent. Perhaps, where nature possesses the strength to cast off the cause of the distress, there is more power indicated; but after an emetic, I have known a dog fall upon its side, and never rise again.

During fits the dog should be confined, to prevent its exhausting itself by wandering about. A large basket is best suited for this purpose. It should be so large as not to incommode the animal, and high enough to allow the dog to stand up without hitting its head. A box is too close; and, besides the objection it presents with regard to air, it does not allow the liquids ejected to drain off.

For the pustular eruption peculiar to distemper, I apply no remedy. When the pustules are matured I open them, but I am not certain any great benefit results from this practice. If the disorder terminates favorably the symptom disappears; and, beyond giving a little additional food, perhaps allowing one meal of meat, from one ounce to six ounces, I positively do nothing in these cases. I must confess I do not understand this eruption; and in medicine, if you are not certain what you should do, it is always safest to do nothing.

The disposition to eat or gnaw any part of the body must be counteracted by mechanical measures. The limb or tail must be encased with leather or gutta percha. No application containing aloes, or any drug the dog distastes, will be of any avail. When the flesh is not sensitive, the palate is not nice, and the dog will eat away in spite of any seasoning. A mechanical obstruction is the only check that can be depended upon. A muzzle must be employed, if nothing else can be used; but generally a leather boot, or gutta percha case moulded to the part, has answered admirably. To the immediate place I apply a piece of wet lint, over which is put some oil silk, and the rag is kept constantly moist. The dose of the liquor arsenicalis is increased by one-fourth or one-half, and in a few days the morbid desire to injure itself ceases. After this the dressings are continued; and only when the recovery is perfect do I attempt to operate, no matter how serious may be the wound, or how terrible, short of mortifying, it may appear.

Tumors must be treated upon general principles: and only regarded as reasons for supporting the strength. They require no special directions at this place, but the reader is referred to that portion of the work in which they are dwelt upon.

To the genital organs of the male, when the discharge is abundant, a wash consisting of a drachm of the solution of the chloride of zinc to an ounce of water, gently applied once or twice daily, is all that will be necessary. The paralysis of the bladder requires immediate attention. In the last stage, when exhaustion sets in, it is nearly always paralysed. Sometimes the retention of urine constitutes the leading and most serious symptom; and after the water has been once drawn off, the bladder may regain its tone – another operation rarely being needed. A professional friend, formerly my pupil, brought to me a dog which exhibited symptoms he could not interpret; it was in the advanced stage of distemper. It was disinclined to move, and appeared almost as if its hind legs were partially paralysed. I detected the bladder was distended, and though the animal did not weigh more than eight pounds, nine ounces and a half of urine were taken away by means of the catheter. From that time it improved, and is now well. There can be no doubt that a few hours' delay in that case would have sealed the fate of the dog. For the manner of introducing the catheter, and the way to discover when the urine is retained, the reader is referred to that part of the present work which treats especially on this subject.

Paralysis and choræa will be here dismissed with a like remark. To those diseases the reader must turn for their treatment; but I must here state, that before any measures specially intended to relieve either are adopted, the original disease should be first subdued, as, in many cases, with the last the choræa will disappear; while in some the twitching will remain through life. All that may be attempted during the existence of distemper, will consist in the addition of from a quarter of a grain to a grain and a half of powdered nux vomica to the tonic pills; and, in severe paralysis, the use of a little friction, with a mild embrocation to the loins.

The treatment during convalescence is by no means to be despised, for here we have to restore the strength, and, while we do so, to guard against a relapse. One circumstance must not be lost sight of; namely, that nature is, after the disease has spent its violence, always anxious to repair the damage it may have inflicted. Bearing this in mind, much of our labor will be lightened, and more than ever shall we be satisfied to play second in the business. The less we do the better; but, nevertheless, there remains something which will not let us continue perfectly idle.

Never, after danger has seemingly passed, permit the animal to return all at once to flesh food. For some time, after all signs of the disease have entirely disappeared, let vegetables form a part, and a good part of the diet. Do not let the animal gorge itself. However lively it may seem to be, and however eager may be its hunger, let the quantity be proportioned to the requirements independent of the voracity. Above all, do not tempt and coax the dog to eat, under the foolish idea that the body will strengthen or fatten, because a great deal is taken into the stomach. We are not nourished by what we swallow, but by that which we digest; and too much, by distending the stomach and loading the intestines, retards the natural powers of appropriation; just as a man may be prevented from walking by a weight which, nevertheless, he may be able to support. Give enough, but divide it into at least three meals – four or five will be better – and let the animal have them at stated periods; taking care that it never at one time has as much as it can eat: and by degrees return to the ordinary mode of feeding.

The fainting fits create great alarm, but, if properly treated, they are very trivial affairs. An ethereal enema, and a dose or two of the medicine, will generally restore the animal. No other physic is needed, but greater attention to the feeding is required. Excessive exercise will cause them, and the want of exercise will also bring them on. The open air is of every service, and will do more for the perfect recovery than almost anything else. When the scarf-skin peels off, a cold bath with plenty of friction, and a walk afterwards, is frequently highly beneficial; but there are dogs with which it does not agree, and, consequently, the action must be watched. Never persevere with anything that seems to be injurious. If the mange breaks out, a simple dressing as directed for that disease will remove it, no internal remedies being in such a case required.