полная версия

полная версияThe Lenâpé and their Legends

They rarely attempted to set forth the divinity in image. The rude representation of a human head, cut in wood, small enough to be carried on the person, or life size on a post, was their only idol. This was called wsinkhoalican. They also drew and perhaps carved emblems of their totemic guardian. Mr. Beatty describes the head chief's home as a long building of wood: "Over the door a turtle is drawn, which is the ensign of this particular tribe. On each door post was cut the face of a grave old man."[139]

Occasionally, rude representations of the human head, chipped out of stone, are exhumed in those parts of Pennsylvania and New Jersey once inhabited by the Lenape.[140] These are doubtless the wsinkhoalican above mentioned.

Doctrine of the SoulThere was a general belief in a soul, spirit or immaterial part of man. For this the native words were tschipey and tschitschank (in Brainerd, chichuny). The former is derived from a root signifying to be separate or apart, while the latter means "the shadow."[141]

Their doctrine was that after death the soul went south, where it would enjoy a happy life for a certain term, and then could return and be born again into the world. In moments of spiritual illumination it was deemed possible to recall past existences, and even to remember the happy epoch passed in the realm of bliss.[142]

The path to this abode of the blessed was by the Milky Way, wherein the opinion of the Delawares coincided with that of various other American nations, as the Eskimos, on the north, and the Guaranis of Paraguay, on the south.

The ordinary euphemism to inform a person that his death was at hand was: "You are about to visit your ancestors;"[143] but most observers agree that they were a timorous people, with none of that contempt of death sometimes assigned them.[144]

The Native PriestsAn important class among the Lenape were those called by the whites doctors, conjurers, or medicine men, who were really the native priests. They appear to have been of two schools, the one devoting themselves mainly to divination, the other to healing.

According to Brainerd, the title of the former among the Delawares, as among the New England Indians, was powwow, a word meaning "a dreamer;" Chip., bawadjagan, a dream; nind apawe, I dream; Cree, pawa-miwin, a dream. They were the interpreters of the dreams of others, and themselves claimed the power of dreaming truthfully of the future and the absent.[145] In their visions their guardian spirit visited them; they became, in their own words, "all light," and they "could see through men, and knew the thoughts of their hearts."[146] At such times they were also instructed at what spot the hunters could successfully seek game.

The other school of the priestly class was called, as we are informed by Mr. Heckewelder, medeu.[147] This is the same term which we find in Chipeway as mide (medaween, Schoolcraft), and in Cree as mitew, meaning a conjurer, a member of the Great Medicine Lodge.[148] I suspect the word is from m'iteh, heart (Chip. k'ide, thy heart), as this organ was considered the source and centre of life and the emotions, and is constantly spoken of in a figurative sense in Indian conversation and oratory.

Among the natives around New York Bay there was a body of conjurers who professed great austerity of life. They had no fixed homes, pretended to absolute continence, and both exorcised sickness and officiated at the funeral rites. Their name, as reported by the Dutch, was kitzinacka, which is evidently Great Snake (gitschi, achkook). The interesting fact is added, that at certain periodical festivals a sacrifice was prepared, which it was believed was carried off by a huge serpent.[149]

When the missionaries came among the Indians, the shrewd and able natives who had been accustomed to practice on the credulity of their fellows recognized that the new faith would destroy their power, and therefore they attacked it vigorously. Preachers arose among them, and claimed to have had communications from the Great Spirit about all the matters which the Christian teachers talked of. These native exhorters fabricated visions and revelations, and displayed symbolic drawings on deerskins, showing the journey of the soul after death, the path to heaven, the twelve emetics and purges which would clean a man of sin, etc.

Such were the famed prophets Papunhank and Wangomen, who set up as rivals in opposition to David Zeisberger; and such those who so constantly frustrated the efforts of the pious Brainerd. Often do both of these self-sacrificing apostles to the Indians complain of the evil influence which such false teachers exerted among the Delawares.[150]

The existence of this class of impostors is significant for the appreciation of such a document as the Walam Olum. They were partially acquainted with the Bible history of creation; some had learned to read and write in the mission schools; they were eager to imitate the wisdom of the whites, while at the same time they were intent on claiming authentic antiquity and originality for all their sayings.

Religious CeremoniesThe principal sacred ceremony was the dance and accompanying song. This was called kanti kanti, from a verbal found in most Algonkin dialects with the primary meaning to sing (Abnaki, skan, je danse et chante en même temps, Rasles; Cree, nikam; Chip., nigam, I sing). From this noisy rite, which seems to have formed a part of all the native celebrations, the settlers coined the word cantico, which has survived and become incorporated into the English tongue.

Zeisberger describes other festivals, some five in number. The most interesting is that called Machtoga, which he translates "to sweat." This was held in honor of "their Grandfather, the Fire." The number twelve appears in it frequently as regulating the actions and numbers of the performers. This had evident reference to the twelve months of the year, but his description is too vague to allow a satisfactory analysis of the rite.

CHAPTER IV

The Literature And Language Of The Lenape

§ 1. Literature of the Lenape Tongue – Campanius; Penn; Thomas,

Zeisberger; Heckeweider, Roth, Ettwein; Grube, Dencke;

Luckenbach; Henry; Vocabularies, a native letter.

§ 2. General Remarks on the Lenape.

§ 3. Dialects of the Lenape.

§ 4. Special Structure of the Lenape. – The Root and the Theme;

Prefixes; Suffixes; Derivatives, Grammatical Notes.

§ 1. Literature of the Lenape TongueThe first study of the Delaware language was undertaken by the Rev. Thomas Campanius (Holm), who was chaplain to the Swedish settlements, 1642-1649. He collected a vocabulary, wrote out a number of dialogues in Delaware and Swedish, and even completed a translation of the Lutheran catechism into the tongue. The last mentioned was published in Stockholm, in 1696, through the efforts of his grandson, under the title, Lutheri Catechismus, Ofwersatt pä American-Virginiske Spräket, 1 vol., sm. 8vo, pp. 160. On pages 133-154 it has a Vocabularium Barbaro-Virgineorum, and on pages 155-160, Vocabula Mahakuassica. The first is the Delaware as then current on the lower river, the second the dialect of the Susquehannocks or Minquas, who frequently visited the Swedish settlements.

Although he managed to render all the Catechism into something which looks like Delaware, Campanius' knowledge of the tongue was exceedingly superficial. Dr. Trumbull says of his work: "The translator had not learned even so much of the grammar as to distinguish the plural of a noun or verb from the singular, and knew nothing of the "transitions" by which the pronouns of the subject and object are blended with the verb."[151]

At the close of his "History of New Sweden," Campanius adds further linguistic material, including an imaginary conversation in Lenape, and the oration of a sachem. It is of the same character as that found in the Catechism.

After the English occupation very little attention was given to the tongue beyond what was indispensable to trading. William Penn, indeed, professed to have acquired a mastery of it. He writes: "I have made it my business to understand it, that I might not want an interpreter on any occasion."[152] But it is evident, from the specimens he gives, that all he studied was the trader's jargon, which scorned etymology, syntax and prosody, and was about as near pure Lenape as pigeon English is to the periods of Macaulay.

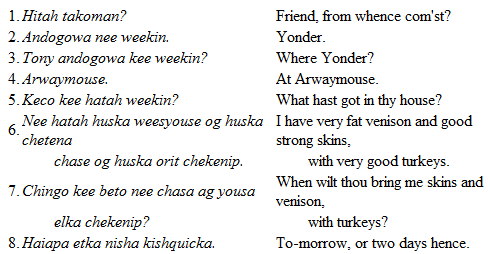

An ample specimen of this jargon is furnished us by Gabriel Thomas, in his "Historical and Geographical Account of the Province and Country of Pensilvania; and of West-New-Jersey in America," London, 1698, dedicated to Penn. Thomas tells us that he lived in the country fifteen years, and supplies, for the convenience of those who propose visiting the province, some forms of conversation, Indian and English. I subjoin a short specimen, with a brief commentary: —

1. Hitah for n'ischu (Mohegan, nitap), my friend; takoman, Zeis. takomun, from ta, where, k, 2d pers. sing.

2. Andogowa, similar to undachwe, he comes, Heck.; nee, pron. possess. 1st person; weekin = wikwam, or wigwam. "I come from my house."

3. Tony, = Zeis. tani, where? kee, pron. possess. 2d person.

4. Arwaymouse was the name of an Indian village, near Burlington, N. J.

5. Keco, Zeis. koecu, what? hatah, Zeis. hattin, to have.

6. Huska, Zeis. husca, "very, truly;" wees, Zeis. wisu, fatty flesh, youse, R. W. jous, deer meat; og, Camp. ock, Zeis. woak and; chetena, Zeis. tschitani, strong; chase, Z. chessak, deerskin; orit, Zeis. wulit, good; chekenip, Z. tschekenum, turkey.

7. Chingo, Zeis. tschingatsch, when; beto, Z. peten, to bring; etka, R. W., ka, and.

8. Halapa, Z. alappa, to-morrow; nisha, two; kishquicka, Z. gischgu, day, gischguik, by day.

The principal authority on the Delaware language is the Rev. David Zeisberger, the eminent Moravian missionary, whose long and devoted labors may be accepted as fixing the standard of the tongue.

Before him, no one had seriously set to work to master the structure of the language, and reduce it to a uniform orthography. With him, it was almost a lifelong study, as for more than sixty years it engaged his attention. To his devotion to the cause in which he was engaged, he added considerable natural talent for languages, and learned to speak, with almost equal fluency, English, German, Delaware and the Onondaga and Mohawk dialects of the Iroquois.

The first work he gave to the press was a "Delaware Indian and English Spelling Book for the Schools of the Mission of the United Brethren," printed in Philadelphia, 1776. As he did not himself see the proofs, he complained that both in its arrangement and typographical accuracy it was disappointing. Shortly before his death, in 1806, the second edition appeared, amended in these respects. A "Hymn Book," in Delaware, which he finished in 1802, was printed the following year, and the last work of his life, a translation into Delaware of Lieberkuhn's "History of Christ," was published at New York in 1821.

These, however, formed but a small part of the manuscript materials he had prepared on and in the language. The most important of these were his Delaware Grammar, and his Dictionary in four languages, English, German, Onondaga and Delaware.

The MS. of the Grammar was deposited in the Archives of the Moravian Society at Bethlehem, Pa. A translation of it was prepared by Mr. Peter Stephen Duponceau, and published in the "Transactions of the American Philosophical Society," in 1827.

The quadrilingual dictionary has never been printed. The MS. was presented, along with others, in 1850, to the library of Harvard College, where it now is. The volume is an oblong octavo of 362 pages, containing about 9000 words in the English and German columns, but not more than half that number in the Delaware.

A number of other MSS. of Zeisberger are also in that library, received from the same source. Among these are a German-Delaware Glossary, containing 51 pages and about 600 words; a Delaware-German Phrase Book of about 200 pages; Sermons in Delaware, etc., mostly incomplete studies, but of considerable value to the student of the tongue.[153]

Associated with Zeisberger for many years was the genial Rev. John Heckewelder, so well known for his pleasant "History of the Indian Nations of Pennsylvania," his interpretations of the Indian names of the State, and his correspondence with Mr. Duponceau. He certainly had a fluent, practical knowledge of the Delaware, but it has repeatedly been shown that he lacked analytical power in it, and that many of his etymologies as well as some of his grammatical statements are erroneous.

Another competent Lenapist was the Rev. Johannes Roth. He was born in Prussia in 1726, and educated a Catholic. Joining the Moravians in 1748, he emigrated to America in 1756, and in 1759 took charge of the missionary station called Schechschiquanuk, on the west bank of the Susquehanna, opposite and a little below Shesequin, in Bradford county, Pennsylvania. There he remained until 1772, when, with his flock, fifty-three in number, he proceeded to the new Gnadenhütten, in Ohio. There a son was born to him, the first white child in the area of the present State of Ohio. In 1774 he returned to Pennsylvania, and after occupying various pastorates, he died at York, July 22d, 1791.

Roth has left us a most important work, and one hitherto entirely unknown to bibliographers. He made an especial study of the Unami dialect of the Lenape, and composed in it an extensive religious work, of which only the fifth part remains. It is now in the possession of the American Philosophical Society, and bears the title: —

Ein Versuch!der Geschichte unsers Herrn u. HeylandesJesu Christiin dass Delawarische übersetzt der Unami von der Marter Woche an bis zurHimmelfahrt unsers Herrn imYahr 1770 u. 72 zu Tschechschequanüng an der SusquehannaWuntschi mesettschawi tipatta lammowewoagan sekauchsianupWulapensuhalinen, Woehowaolan Nihillalijeng mPatamauwossThe next page begins, "Der fünfte Theil," and § 86, and proceeds to § 139. It forms a quarto volume, of title, 9 pages of contents in German and English, and 268 pages of text in Unami, written in a clear hand, with many corrections and interlineations.

This is the only work known to me as composed distinctively in the Unami, and its value is proportionately great as providing the means of studying this, the acknowledged most cultivated and admired of the Lenape dialects.

It will be the task of some future Lenape scholar to edit its text and analyze its grammatical forms. But I believe that Algonkin students will be glad to see at this time an extract from its pages.

I select § 96, which is the parable of the marriage feast of the king's son, as given in Matthew xxii, 1-14.

1. Woak Jesus wtabptonalawoll woak lapi nuwuntschi

And Jesus he-spoke-with-them and again he-began

Enendhackewoagannall nelih* woak wtellawoll.

parables them-to and he-said-to-them.

{wtellgigui}

2. Ne Wusakimawoagan Patamauwoss {mallaschi }

The his-kingdom God it-is-like

mejauchsid* Sakima, na Quisall mall'mtauwan Witachpungewiwuladtpoàgan.

certain king, his-son be-made-for-him marriage.

3. Woak wtellallocàlan wtallocacannall, wentschitsch nek

And he-sent-out his-servants the-bidding the

Elendpannik lih* Witachpungewiwuladtpoàgannung wentschimcussowoak;

those-bidden to marriage those-who-were-bidden,

tschuk necamawa schingipawak.

but they they-were-unwilling.

4. Woak lapi wtellallocàlan pih wtallocacannall woak

And again he-sent-out other servants and

{panni} {penna }

wtella {wolli} Mauwnoh nen Elendpanmk, {schita}

he-said-to-them those the-bidden

Nolachtuppoágan 'nkischachtuppui, nihillalachkik Wisuhengpannik

The-feast I-have-made-the-feast, they-are-killed they-fattened-them

auwessissak nemætschi nhillapannick woak weemi ktakocku 'ngischachtuppui,

beasts the-whole I-killed-them and all I-have-finished

peeltik lih Witachpungkewiwuladtpoàgannung.

come to marriage.

5. Tschuk necamawa mattelemawoawollnenni, woak ewak

But they they-esteemed-it-not and went

ika, mejauchsid enda wtakihàcannung, napilli

away certain thither to-his-plantation-place other

nihillatschi {M'hallamawachtowoagannung }

{ Nundauchsowoagannung }.

to-merchandise-place

6. Tschuk allende wtahunnawoawoll neca allocacannall

But some they-seized-them those servants

{ quochkikimawoawoll }

{popochpoalimawoawoll} woak wumhillawoawoll necamawa.

they-beat-them and they-killed-them they.

7. Elinenni na* Sakima pentanke, nannen lachxu,

When the king heard therefore he-was-angry,

woak wtellallokalan Ndopaluwinuwak, woak wumhillawunga

and he-sent-them warriors and he-slew

jok Nehhillowetschik, woak wulusumen Wtutèn'nejuwaowoll.

these murderers, and he-destroyed their-cities.

{woll }

8. Nannen wtella {panni} nelih wtallocacannall: Ne

Then he-said-to-them to his-servants The

Witachpungkewiwuladtpoagan khella nkischachtuppui, tschuk

marriage truly I-have-prepared-it but

{attacu uchtàpsiwunewo}

nek Elendpannick {wtopielgique juwunewo}.

the those-bidden are-not-to-sit-down-worthy.

9. Nowentschi allmussin ikali mengichungi Ansijall, woak

Therefore go-ye-away thither to-some-places roads and

winawammoh lih Witachpungkewiwuladtpoagan; na natta

ask-ye-them to marriage those

aween kiluwa mechkaweek (oh).

whom ye find.

10. Woak nek Allocacannak iwak ikali menggichüngi

And the servants they-went thither to-some-places

Aneijall, woak mawehawoawoll peschuwoawak na natta

roads and they-brought-them-together those

aween machkawoachtid, Memannungsitschik woak Wewulilossitschik,

whom they-found-them the-bad-ones and the good-ones

woak nel* Ehendachpuingkill weemi tæphikkawachtinewo.

and the at-the-tables all they-seated.

11. Nannen mattemikæùh na Sakima, nek Elendpannik mauwi

Then he-entered-in the king the those-bidden

pennawoawoll, woak wunewoawoll uchtenda mejauchsid Lenno,

he-saw-them and he-saw-him there certain man

na matta uchtellachquiwon witachpungkewi Schakhokquiwan.

the not wearing a marriage coat.

12. Woak wtellawoll neli,* Elanggomêllen, ktelgiquiki matte

And he-said-to-him to-him Friend like not

attemikēn jun (or tá elinàquo wentschi jun k'mattîmikeen,)

ashamed here not like therefore here thou-art-ashamed

woak {müngachsa*} mattacu witachpungkewi Schakhokquiwan

and { ilik*} not marriage coat

ktellachquiwon? Necama tschuk k'pettúneù.

thou wearest He but He-mouth-shuts.

13. Nannen w'tellawoll na Sakima nelih* Wtallocacannüng;

Then he-said-to-them the king to-them his-servants

{ nan }

Kachpiluh {woan} Wunachkall woak W'sittall, woak

Fasten-ye-him his-hands and his-feet and

lannéhewik quatschemung enda achwipegnunk, nitschlenda

throw-him where in pitch-darkness even-some

Lipackcuwoagan woak Tschætschak koalochinen.

weeping and teeth-gnashing.

14. Ntitechquoh macheli moetschi wentschimcussuwak, tschuk

Because many they-are-called but

tatthiluwak achnaeknuksitschik.

they-are-few the-chosen.

The asterisk occurs in the original apparently to indicate that a word is superfluous or doubtful. The interlined translation I have supplied from the materials in the mission-Delaware dialect, but my resources have not been sufficient to analyze each word; and this, indeed, is not necessary for my purpose, which is merely to present an example of the true Unami dialect.

The Moravian Bishop, John Ettwein, was another of their fraternity who applied himself to the study of the Delaware. Born in Europe in 1712, he came to the New World in 1754, and died at the great age of ninety years in 1802. He prepared a small dictionary and phrase book, especially rich in verbal forms. It is an octavo MS. of 88 pages, without title, and comprises about 1300 entries. This manuscript exists in one copy only, in the Moravian Archives at Bethlehem.

Bishop Ettwein also prepared for General Washington, in 1788, an account of the traditions and language of the natives, including a vocabulary. This was found among the Washington papers by Mr. Jared Sparks, and was published in the "Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Historical Society," 1848.

One of the most laborious of the Moravian missionaries was the Rev. Adam Grube. His life spanned nearly a century, from 1715, when he was born in Germany, until 1808, when he died in Bethlehem, Pa. Many years of this were spent among the Delawares in Pennsylvania and Ohio. He was familiar with their language, but the only evidence of his study of it that has come to my knowledge is a MS. in the Harvard College Library, entitled, "Einige Delawarische Redensarten und Worte." It has seventy-five useful leaves, the entries without alphabetic arrangement, some of the verbs accompanied by partial inflections. The only date it bears is "Oct. 10, 1800," when he presented it to the Rev. Mr. Luckenbach, soon to be mentioned.

After the War of 1812 the Moravian brother, Rev. C. F. Dencke, who, ten years before had attempted to teach the Gospel to the Chipeways, gathered together the scattered converts among the Delawares at New Fairfield, Canada West. In 1818 he completed and forwarded to the Publication Board of the American Bible Society a translation of the Epistles of John, which was published the same year.

He also stated to the Board that at that time he had finished a translation of John's Gospel and commenced that of Matthew, both of which he expected to send to the Board in that year. A donation of one hundred dollars was made to him to encourage him in his work, but for some reason the prosecution of his labors was suspended, and the translation of the Gospels never appeared (contrary to the statements in some bibliographies).

It is probable that Mr. Dencke was the compiler of the Delaware Dictionary which is preserved in the Moravian Archives at Bethlehem. The MS. is an oblong octavo, in a fine, but beautifully clear hand, and comprises about 3700 words. The handwriting is that of the late Rev. Mr. Kampman, from 1840 to 1842 missionary to the Delawares on the Canada Reservation. On inquiring the circumstances connected with this MS., he stated to me that it was written at the period named, and was a copy of some older work, probably by Mr. Dencke, but of this he was not certain.

While the greater part of this dictionary is identical in words and rendering with the second edition of Zeisberger's "Spelling Book" (with which I have carefully compared it), it also includes a number of other words, and the whole is arranged in accurate alphabetical order.

Mr. Dencke also prepared a grammar of the Delaware, as I am informed by his old personal friend, Rev. F. R. Holland, of Hope, Indiana; but the most persistent inquiry through residents at Salem, N. C., where he died in 1839, and at the Missionary Archives at Bethlehem, Pa., and Moraviantown, Canada, have failed to furnish me a clue to its whereabouts. I fear that this precious document was "sold as paper stock," as I am informed were most of the MSS. which he left at his decease! A sad instance of the total absence of intelligent interest in such subjects in our country.