полная версия

полная версияThe Lenâpé and their Legends

The Rev. Abraham Luckenbach may be called the last of the Moravian Lenapists. With him, in 1854, died out the traditions of native philology. Born in 1777, in Lehigh county, Pennsylvania, he became a missionary among the Indians in 1800, and until his retirement, forty-three years later, was a zealous pastor to his flock on the White river, Indiana, and later, on the Canada Reservation. His published work is entitled "Forty-six Select Scripture Narratives from the Old Testament, embellished with Engravings, for the Use of Indian Youth. Translated into Delaware Indian, by A. Luckenbach. New York. Printed by Daniel Fanshaw, 1838." 8vo, pp. xvi, 304.

After his retirement in Bethlehem, he edited, in 1847, the second edition of Zeisberger's "Collection of Hymns," the first of which has already been mentioned.

A short MS. vocabulary, in German and Delaware, is in the possession of his family, in Bethlehem, and some loose papers in the language.

One of the most recent students of the Delaware was Mr. Matthew G. Henry, of Philadelphia. In 1859 and 1860 he compiled, with no little labor, a "Delaware Indian Dictionary," the MS. of which, in the library of the American Philosophical Society, forms a thick quarto volume of 843 pages, with a number of maps. It is in three parts; 1, English and Delaware; 2, Delaware and English; 3, Delaware Proper Names and their Translations.

It includes, without analysis or correction, the words in Zeisberger's "Spelling Book," Roger William's "Key," Companius' Vocabulary, those in Smith's and Strachey's "Virginia" and various Nanticoke, Mohegan, Minsi and other vocabularies. The derivations of the proper names are chiefly from Heckewelder, and in other cases are venturesome. The compilation, therefore, while often useful, lacks the salutary check of a critical, grammatical erudition, and in its present form is of limited value.

Some of the later vocabularies collected by various travelers offer points for comparison, and may be mentioned here.

In 1786 Major Denny[154] at Fort McIntosh, Ohio, collected a number of Delaware words, principally from Shawnee Indians. A comparison shows many of them to be in a corrupt form, owing either to the ignorance of the Shawnee authority, or to the inaccuracy of Major Denny in catching the sounds.

While engaged on the Pacific Railroad survey, in 1853, Lieut. Whipple[155] collected a vocabulary of a little over 200 words from a Delaware chief, named Black Beaver, in the Indian Territory, which was edited, in 1856, by Prof. Turner. It is evidently a pure specimen, and, as the editor observes, "agrees remarkably" with earlier authentic vocabularies.

In the second volume of Schoolcraft's large work[156] is a vocabulary of about 350 words, obtained by Mr. Cummings, U. S. Indian Agent. The precise source, date and locality are not given, but it is evidently from some trustworthy native, and is quite correct.

Some small works for the schools of the Baptist missions among the Delawares in Kansas were prepared by the Rev. J. Meeker. They appear to be entirely elementary in character.

It will be observed that in this list not a single native writer is named. So far as I have ascertained, though many learned to write their native tongue, not one attempted any composition in it beyond the needs of daily life.

To make some amends for this, and as I wished to obtain an example of the Lenape of to-day, I asked Chief Gottlieb Tobias, an educated native on the Moravian Reservation in Canada, to give me in writing his opinion of the Delaware text of the Walum Olum, which I had sent him. This he obligingly did, and added a translation of his letter. The two are as follows, without alteration: —

Moraviantown, Sept. 26, 1884.I, Gottlieb Tobias,

Nanne ni ngutschi nachguttemin, jun awen eet ma elekhigetup. Woak alende nenostamen woak alende taku eli wtallichsin elewondasik wiwonalatokowo pachsi wonamii lichsu woak pachsi pilli lichsoagan. Taku ni nenostamowin. Lamoe nemochomsinga achpami eet newinachke woak chash tichi kachtin nbibindameneb nin lichsoagan. Mauchso lenno woak mauchso chauchshissis woak juque mauchso chauchshissis achpo pomauchsu igabtshi lue wiwonallatokowo won bambil alachshe. Woak lue lamoe ni enda. Mimensiane ntelsitam alowi ayachichson won elhagewit woak ehelop ne likhiqui. Gichgi wonami lichso shuk tatcamse woak gichgi minsiwi lichso.

TranslationThen I will try to answer this (which) some one at some time wrote. And some I understand, and some not, because his language is called Wonalatoko, half Unami and half another language. I do not understand it. Long ago my grandfather about 48 years ago I heard it that language. One man and one old woman and now another old woman here lives yet who uses this Wonalatoko language just like this book and she said, I of old time when I was a child heard more difficult dialect than the present, and many at that time partly Unami he speak, but sometimes also partly Minsi he speak.

The drift of Chief Tobias' letter is highly important to this present work, though his expressions are not couched in the most perfect English. It will be noted that he recognizes the text of the Walum Olum to be a native production composed in one of the ancient southern dialects of the tongue, the Unami (Wonami) or the Unalachtgo (Wonalatoko). I shall recur to this when discussing the authenticity of that document on a later page.

§ 2. General Remarks on the LenapeThe Lenape language is a well-defined and quite pure member of the great Algonkin stock, revealing markedly the linguistic traits of this group, and standing philologically, as well as geographically, between the Micmac of the extreme east and the Chipeway of the far West.

These linguistic traits, common to the whole stock, I may briefly enumerate as follows: —

1. All words are derived from simple, monosyllabic roots, by means of affixes and suffixes.

2. The words do not come within the grammatical categories of the Aryan language, as nouns, adjectives, verbs and other "parts of speech," but are "indifferent themes," which may be used at will as one or the other. To this there appear to be a few exceptions.

3. Expressions of being (i. e., nominal themes) undergo modifications depending on the ontological conception as to whether the thing spoken of is a living or a lifeless object. This forms the "animate and inanimate," or the "noble and ignoble" declensions and conjugations. The distinction is not strictly logical, but largely grammatical, many lifeless objects being considered living, and the reverse. This is the only modification of the kind known, true grammatical gender not appearing in any of these tongues.

4. Expressions of action (i. e., verbal themes) undergo modifications depending on the abstract assumption as to whether the action is real or conjectural. If the latter, it is indicated by a change in the vowel of the root. This leads to a fundamental division of verbal modes into positive and suppositive modes.

5. The expression of action is subordinate to that of being, so that the verbal elements of a proposition are secondary to the nominal or pronominal elements, and the subjective relation becomes closely akin to, or identical with, that of possession.[157]

6. The conception of number is feebly developed in its application to inanimate objects, which often have no grammatical plurals. The inclusive and exclusive plurals are used in the first person.

7. The genius of the language is holophrastic– that is, its effort is to express the relationship of several ideas by combining them in one word. This is displayed: 1, in nominal themes, by polysynthesis, by which several such themes are welded into one, according to fixed laws of elision and euphony; and 2, by incorporation, where the object (or a pronoun representing it) and the subject are united with the verb, forming the so-called "transitions," or "objective conjugations."

8. There is no relative pronoun, so that the relation of minor to major clauses is left to be indicated either by position or the offices of a simple connective.

9. The language of both sexes is identical, those differences of speech between the males and females, so frequently observed in other American tongues, finding no place in the Algonkin.

10. No independent verb-substantive is found, and, as might be anticipated, no means of predicating existence apart from quality and attribute.

§ 3. Dialects of the LenapeTwo slightly different dialects prevailed among the Delawares themselves, the one spoken by the Unami and Unalachtgo, the other by the Minsi. The former is stated by the Moravian missionaries to have had an uncommonly soft and pleasant sound to the ear[158], and William Penn made the same remark. It was also considered to be the purer and more elegant dialect, and was preferred by the missionaries as the vehicle for their translations.

The Minsi was harsher and more difficult to learn, but would seem to have been the more archaic branch, as it is stated to be a key to the other, and to preserve many words in their integrity and original form, which in the Unami were abbreviated or altogether dropped. The Minsi dialect was closely akin to the Mohegan.

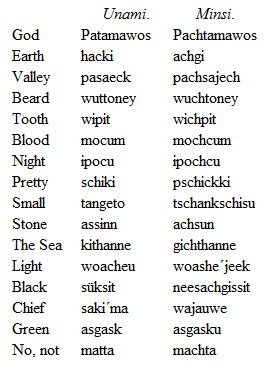

How far the separation of the Delaware dialects had extended may be judged from the subjoined list of words. They are selected, as showing the greatest variation, from a list of over one hundred, prepared by Mr. Heckewelder for the American Philosophical Society, and preserved in MS. in its library.

The comparison proves that the differences are far from extensive, and chiefly result from a greater use of gutturals.

COMPARISON OF THE UNAMI AND MINSI DIALECTS

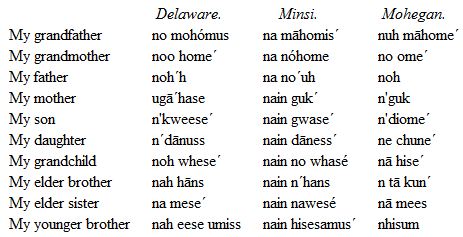

What differences there were have been retained and perhaps accentuated in modern times, if we may judge from the names of consanguinity obtained by Mr. Lewis H. Morgan on the Kansas Reservation in 1860. These are given in part in the annexed table, and the Mohegan is added for the sake of extending the comparison.

A noteworthy difference in the Northern and Southern Lenape dialects was that the latter possessed the three phonetic elements n, l and r, while the former could not pronounce the r, and their neighbors, the Mohegans, neither the l nor the r.

The dialect studied by Campanius and Penn, and that in southern New Jersey presented the r sound where the Upper Unami and Minsi had the l. Thus Campanius gives rhenus, for lenno, man; and Penn oret, for the Unami wulit, good.

The dialectic substitution of one of these elements for another is a widespread characteristic of Algonkin phonology. Roger Williams early called attention to it among the tribes of New England.[159]

Tracing it to its origin, it clearly arises from the use of "alternating consonants," so extensive in American languages. In very many of them it is optional with the speaker to employ any one of several sounds of the same class. This is the case with these letters in Cree, which, for various reasons, may be considered the most archaic of all the Algonkin dialects. In its phonetics, the th, y, l, n and r are "permuting" or "alternating" letters.[160]

Often, too, the sound falls between these letters, so that the foreign ear is left in doubt which to write.

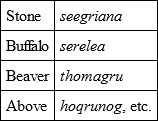

That this is the case with the Delaware is evident from some of the more recent vocabularies where the r is not infrequent. The following words, from the vocabulary in Major Denny's Memoir, illustrate this: —

Even Mr. Lewis A. Morgan, who had considerable practice in writing the sounds of the Indian languages, inserts the r in a number of pure Delaware words he collected in Kansas.[161]

Another difficulty presents itself in the sibilants. They are not always distinguished.

Mr. Horatio Hale writes me on this point: "In Minsi, and perhaps in all the Lenape dialects, the sound written s is intermediate between s and th (the Greek Θ). This element is pronounced by placing the tongue and teeth in the position of the theta, and then endeavoring to utter s".

The guttural, represented in the Moravian vocabularies by ch, was softened by the English likewise to the s sound, as it appears also to have been by the New Jersey tribes.[162]

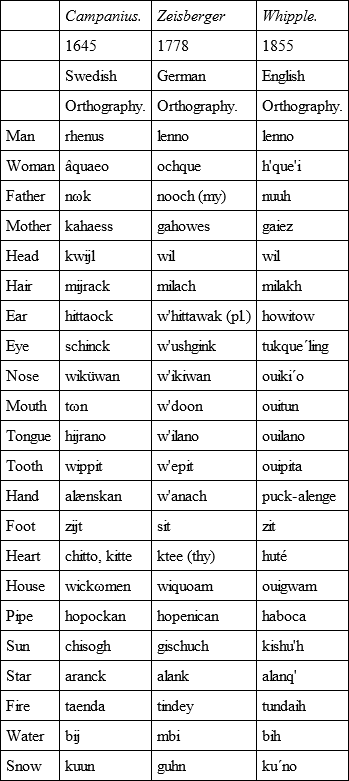

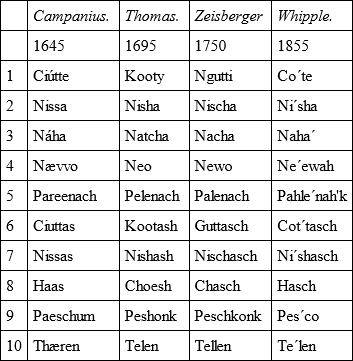

In connection with dialectic variation, the interesting question arises as to the rapidity of change in language. With regard to the Lenape we are enabled to compare this for a period covering more than two centuries. To test it, I have arranged the subjoined table of words culled from three writers at about equidistant points in this period. Each wrote in the orthography of his own tongue, and this I have not altered. The words from Campanius are from the southern dialect, which preferred the r to the l, and this substitution should be allowed for in a fair comparison.

COMPARISON OF THE DELAWARE AT INTERVALS DURING 210 YEARS

I have no doubt that if a Swede, a German and an Englishman were to-day to take down these words from the mouth of a Delaware Indian, each writing them in the orthography of his own tongue, the variations would be as numerous as in the above list, except, perhaps, the ancient and now disused r sound. The comparison goes to show that there has probably been but a very slight change in the Delaware, in spite of the many migrations and disturbances they have undergone. They speak the language of their forefathers as closely as do the English, although no written documents have aided them in keeping it alive. This is but another proof added to an already long list, showing that the belief that American languages undergo rapid changes is an error.

The dialect which the Moravian missionaries learned, and in which they composed their works, was that of the Lehigh Valley. That it was not an impure Minsi mixed with Mohegan, as Dr. Trumbull seems to think,[163] is evident from the direct statements of the missionaries themselves, as well as from Heckewelder's Minsi vocabularies, which show many points of divergence from the printed books. Moreover, among the first converts from the Delaware nation were members of the Unami or Turtle tribe, and Zeisberger was brought into immediate contact with them.[164] We may fairly consider it to have been the upper or inland Unami, which, as I have said, was recognized by the nation as the purest, or at least the most polished dialect of their tongue. It stood midway between the Unalachtgo and Southern Unami and the true Minsi.

§ 4. Special Structure of the LenapeThe Root and the Formation of the Theme.– As they appear in the language of to-day, the Lenape radicals are chiefly monosyllables, which undergo more or less modifications in composition. They cannot be used alone, the tongue having long since passed from that interjectional condition where each of these roots conveyed a whole sentence in itself.

Whether they can be resolved back into a few elementary sounds, primitive elements of speech, I shall not discuss. This has been done for the Cree roots by Mr. Joseph Howse,[165] and most of the radicals of that tongue are identical with those of the Lenape. Some of his conclusions appear to me hazardous and hypothetical; and certainly many of his supposed analogies drawn from European tongues are extravagant.

As in other idioms, so in Lenape, two or more radicals may be compounded to form a combination, which, in turn, performs the offices of a radical in the construction of themes.

This combination is formed either by prefixes or suffixes. The prefixes are generally adjectival in signification, while the suffixes are usually classificatory. A number of these are secondary roots, which are themselves capable of further analysis.

As so much of the strength of the languages depends on this plan of word building, I have drawn off a list of a few of the more frequent affixes of the Lenape, with their signification: —

Lenape Prefixes.

awoss-, beyond, the other side of.

eluwi-, most, a superlative form.

gisch-, see page 102.

kit-, great, large.

lappi-, again, indicates repetition.

lenno-, male, man.

lippoe-, wise, shrewd; as lippoeweno, a shrewd man.

mach-, evil, bad, hurt.

matt-, negative and depreciatory;

as mattaptonen, to speak uncivilly.

ni-, see page 101.

ochque-, she, female.

pach-, division, separation; pachican, a knife;

pachat, to split.

pal-, negative, as dis- or in-,

from palli otherwheres.

tach-, pairs or doubles.

tschitsch-, indicates repetition.

wit-, with or in common.

wul-, or wel-, see page 104.

Many of these are abbreviated to the extent that a single significant letter is all that remains, as min in msim, hickory nut; pakihm, cranberry; and so acki to k, hanne to an, as kitanink (Kittanning), from gitschi, great; hanne, flowing river; ink, locative, "at the place of the great river."

Lenape Suffixes.

-ak, wood, from tachan; kuwenchak, pine wood.

-aki, place, land.

-ammen, acceptance, adoption; wulistamen,

I accept it as good, I believe it. See page 104.

-ape, male, man. From a root ap, to cover (carnally).

In Chipeway applied only to lower animals.

-atton, or hatton, to have, to put somewhere.

The radical is ãt. Also a prefix, as,

hattape, the bow; lit., what the man has.

-bi, tree; machtschibi, papaw tree.

-chum, a quadruped.

-elendam, a verbal termination, signifying a disposition of mind.

The root is en, ne, ni,

I; "it is to me so."

-goot, a snake; from achgook, a serpent.

-hanna, properly hannek, a river; from the root, which appears in Cree as anask, to stretch out along

the ground; mechhannek, a large stream.

Heckewelder derives this from amkamme, a river. The terminal k is, however, part of the root, and not the locative termination. The word is allied to Del. quenek, long.

-hikan, tidal water; kittahikan, the ocean; shajahikan, the sea shore.

-hilleu, it is so, it is true; impersonal form from lissin.

-hittuck, river, water in motion.

-igan, instrumental; also shican and can.

A participial termination used with inanimate objects.-in or ini, of the kind; like; predicative form of the demonstrative pronoun.-ink or unk, place where.

-is or -it, diminutive termination.

-leu, it is so, it is true.

-meek, a fish; maschilamek, a trout.

-min, a fruit.

-peek, a body of still water; menuppek, a lake.

-sacunk, an outlet of a stream into another; also saquik.

-sipu, stream; lit., stretched, extended.

-tin, with, or in common.

-tit, diminutive termination; amentit, a babe.

-wagan, abstract verbal termination;

machelemuxowagan, the being honored.

-wehelleu, a bird.

-wi, the verb-substantive termination, predicating being;

tehek, cold; tehekwi, he or it is cold.

-wi, negative termination in certain verbal forms.

-xit, indicates the passive recipient of the action;

machelemuxit, the one who is honored.

The analysis of a series of derivatives from the same root offers a most instructive subject for investigation in the Lenape. Not only does it reveal the linguistic processes adapted, but it discloses the psychology of the native mind, and teaches us the associations of its ideas, and the range of its imaginative powers. By no other avenue can we gain access to the intimate thought-life of this people. Here it is unfolded to us by evidence which is irrefragable.

These considerations lead me to present a few examples of the derivatives from roots of different classes.

EXAMPLES OF LENAPE DERIVATIVESSubjective Root NI, I, mine.

1. In a good sense.

Nihilleu, it is I, or, mine.

Nihillatschi, self, oneself.

Nihillapewi, free (ape, man = I am my own man).

Nihillapewit, a freeman.

Nihillasowagan, freedom, liberty.

Nihillapeuhen, to make free, to redeem.

Nihillapeuhoalid, the Redeemer, the Saviour.

2. In a bad sense.

Ni´hillan, he is mine to beat, I beat him.

Nihil´lan, I beat him to death, I kill him.

Nihillowen, I put him to death, I murder him.

Nihillowet, a murderer.

Nihillowewi, murderous.

3. In a demonstrative sense.

Ne, pl. nek, or nell, this, that, the.

Nall, nan, nanne, nanni, this one, that one.

Nill, these.

Naninga, those gone, with reference to the dead.

4. In a possessive sense.

Nitaton, in-my-having, I can, I am able, I know how.

Nitaus, of-my-family, sister-in-law.

Nitis, of-mine, a friend, a companion.

Nitsch! my child! exclamation of fondness.

The strangely conflicting ideas evolved from this root already attracted the attention of Mr. Duponceau[166]. That the notions for freedom and servitude, murderer and Saviour, should be expressed by modifications of the same radical is indeed striking! But the psychological process through which it came about is evident on studying the above arrangement.

Objective-intensive root GISCH or KICH (Cree, KIS or KIK).

Signification – successful action.

1. Applied to persons.

A. Initial successful action.

Gischigin, to begin life, to be born.

Gischihan, to form, to make with the hands.

Gischiton, to make ready, to prepare.

Gischeleman, to create with the mind, to fancy.

Gischelendam, to meditate a plan, to lie.

B. Continuous successful action.

Gischikenamen, to increase, to produce fruit.

Giken, to grow better in health.

Gikeowagan, life, health.

Gikey, long-living, old, aged,

C. Final successful action.

Gischatten, finished, ready, done, cooked.

Gischiton, to make ready, to finish.

Gischpuen, to have eaten enough.

Gischileu, it has proved true.

Gischatschimolsin, to have resolved, to have decreed.

Gischachpoanhe, baked, cooked (the bread is).

2. Applied to things.

A. Initial successful action.

Gischuch, sun, moon, day, month. The idea appears to be the beginning of a period of time with the collateral notion of prosperous activity. The correctness of the derivation is shown by the next word.

Gischapan, day-break, beginning day-light.

From wapan, the east, or light.