полная версия

полная версияAn Old New Zealander; or, Te Rauparaha, the Napoleon of the South.

In no respect has the reputation of Te Rauparaha suffered more from bitter hostility than in connection with the Wairau massacre. And we cannot wonder; for at the time of its occurrence he had arrayed against him a galaxy of literary talent, such as the Colony has never seen since, and day by day these wielders of facile pens fed with scholarly vituperation the flames of racial animosity, which were already burning at white heat. They spoke of murder; they clamoured for revenge; and all who failed to see as they saw were exposed to the darts of their merciless sarcasm. But, with the softening influence of time, men's hearts have mellowed, stormy passions have subsided, and we of this day are able to review the facts with more sober judgment than was possible to those who lived and wrote in the heated atmosphere of the time. In this unhappy quarrel it must now be accepted as an established fact that the New Zealand Company were the aggressors. The Wairau Valley may, or may not, have been included in their original purchases; but Captain Wakefield knew that this point was being contested by the natives. He knew further that the dispute had been by them referred to Mr. Spain, and therefore no reasonable excuse can be advanced for his attempt to seize the valley while its title was still subject to judicial investigation. Te Rauparaha's attitude in the early stages of the trouble amounted to no more than a temperate protest. He personally interviewed Captain Wakefield at Nelson; he was as conciliatory in requesting the surveyors to leave the field as he was decided that they must go; he calmed Rangihaeata's violence at the conference with Mr. Tuckett; and, as Mr. Spain's final decision was fatal to the Company's claim, the charge of arson preferred against him dwindles into a legal fiction. The conciliatory tone thus manifested by the chief was equally marked in the more acute stage, which arose at Tua Marina. While the magistrate fumed and raged, the chief stood perfectly calm. He more than once begged that time should be taken to talk over the case; but the mad impetuosity of Thompson would brook no delay in determining a cause the merits of which he, the judge, had already prejudged in his own mind. For the precipitation of the conflict which followed, who shall say that the fault was Te Rauparaha's? It was neither his hand nor his command which put the brand to the bush, nor does it appear that it was ever within his power to control the outburst of human passion which flamed up upon the firing of the first shot. What part he took in the fight is uncertain. It has never been suggested that he bore arms, and therefore we may assume that he was an excited spectator, rather than an active participant in the mêlée. That he was early on the brow of the hill, after the retreat had ceased, would appear to be beyond doubt; but his first act on reaching the Europeans was to shake hands with them, a proceeding which seemed to imply that, even after all that had passed, his friendship had not been irretrievably lost. Indeed, there is nothing to lead us to suppose that he harboured any thoughts of retaliation, until Rangihaeata violently demanded utu for the death of Te Rongo.

This demand placed Te Rauparaha in a serious dilemma. Against any feeling of friendship for the Europeans which may still have lingered in his heart, he had now to set a claim which was wholly in accord with native custom; a right, in fact, which had been recognised by his forefathers for more centuries than we can with certainty name; a feature of Maori justice supported by ages of precedent, and which, imbibed from infancy, had become a part of his nature. This was undoubtedly the crisis of the tragedy. Had Te Rauparaha decided against Rangihaeata, there would have been no massacre; but where his detractors are unfair to him is in appearing to expect that he should have suddenly risen superior to his Maori nature, and, in place of allowing his actions to be governed by Maori law, that he – a heathen – should have viewed the attempt to seize his land and his person, together with the death of Te Rongo, in the forgiving spirit of a Christian. No Ethiop was ever asked to change his skin more rapidly; and if Te Rauparaha failed in the performance of the miracle, he only failed when success was morally impossible to him. In the massacre itself he had no share; and, beyond the fact that, under intense natural excitement, he gave a tacit consent to Rangihaeata's deed, he appears to have stood outside it.

Of his relations with the whalers, accounts vary. If we accept the Wakefield view, we must believe that by them he was heartily detested and distrusted. That he was acquisitive to the point of aggression is possible; that he was often overbearing towards them may be equally true, for these are characteristics frequently seen in the powerful savage; but there are also instances recorded in which he showed a ready generosity and a strict sense of justice towards the whaling community.

"The whalers and traders, who had the best opportunity of being intimately acquainted with him, and that, too, at a time when his power to injure was greatest, invariably spoke of him as ever having been the white man's friend. He always placed the best he had before them, and in no instance have I heard of his doing any one of them an injury. Speaking of him to an old whaler, he said emphatically that Te Rauparaha never let the white man who needed want anything he could give, whether food or clothing; in fact, his natural sagacity told him that it was his interest to make common cause with the Europeans, for it was through them that he acquired the sinews of war, guns, powder, and shot, and everything else that he required."203

The impartiality with which he held the balance between the two races may be gathered from the following incident: A whaleboat had left Waikanae to proceed to Kapiti, the crew taking with them a native, who sat in the bow. On the journey over the Maori managed to secrete beneath his mat the small hatchet which the whalers used to cut the line, and was quietly walking off with it when the boat reached the island. Before he had gone many steps one of the crew whispered to the headsman what had happened, whereupon that worthy picked up the harpoon and drove it straight through the Maori's back, killing him on the spot. The native population was at once thrown into a state of uproar and fury, threatening dire vengeance upon the whalers, but Te Rauparaha quelled the disturbance in an instant, and, after inquiring into its cause, walked away, declaring that the native had only met with his deserts.

Towards his native enemies Te Rauparaha was unquestionably merciless and cruel, though not more so, perhaps, than was sanctioned by the spirit of the times in which he lived. Yet that he was not wholly incapable of admiration for a worthy opponent is shown by his seeking out and sparing Te Ata o Tu, the Ngai-Tahu warrior, who fought so bravely against him at Kaiapoi. Even in this case there are persons who affect to believe that self-interest rather than chivalry may have been the moving impulse in his conduct, for he possibly counted upon so skilful a fighter being invaluable to him in his northern troubles. But surely we can afford to be magnanimous enough to concede to so fine an example of generosity a less mercenary motive?204 Though relentless to a degree towards those tribes who came between him and his ambitions, it must always be remembered that his ruthlessness is not to be judged from the Christian standpoint. His enormities, which were neither few nor small, were those of a savage, born and bred in an atmosphere into which no spirit of Divine charity had ever entered. Compared with the excesses practised in civilised warfare by such champions of the Cross as Cortés and the Duke of Alva, his deeds of darkness become less repugnant, if not altogether pardonable.

The attitude which he adopted towards the European was in exact opposition to that assumed by Te Rangihaeata. He welcomed rather than resented the coming of the white man, although he found reason to protest against the methods employed by the New Zealand Company in acquiring land on which to settle them. Nor in this respect can it be said that his objections were captious or ill-founded; in fact, with the exception of the Hutt dispute, the Commissioner's decisions were invariably a vindication of his contentions. Some doubt has necessarily been cast upon his loyalty to the Government (which he accepted when he signed the Treaty of Waitangi), by virtue of the fact that he was seized and held captive because of his supposed infidelity. There are those with whom it is only necessary to accuse in order to condemn. In this case accusation carried condemnation with it, but condemnation without proof of guilt is injustice. Whatever the measure of Te Rauparaha's duplicity may have been, the Governor conspicuously failed to do more than suspect him, and as conspicuously failed to bring the chief face to face with his accusers. It was never proved, nor was any attempt ever made to prove before a court of competent jurisdiction, that Te Rauparaha had held communication with the enemy. Even if he had so communicated, an easy explanation might have been found in the native practice, under which individuals in opposing forces frequently visited each other during the progress of hostilities. Te Rauparaha had many friends with the rebels, and it would appear perfectly natural to him to hold friendly correspondence with them, whilst himself maintaining an attitude of strict neutrality. Considering the contemptuous disregard which many British officials displayed towards rites and customs held sacred by the Maori, it is not to be expected that they would trouble to understand, or try to appreciate, this subtlety in the native character. And so, what was to the Maori a well-established and common custom, was by them translated into treachery, for which Te Rauparaha was made captive in a manner which leaves us but little right to talk of open and honourable tactics.

His conduct while a captive on board the Calliope appears to have been exemplary enough, and he succeeded in impressing those with whom he came into contact by his quick perception, particularly of anything meant to turn him into ridicule, of which he was most sensitive. He frequently became much excited and very violent, and at other times, when talking of his misfortunes, he would become deeply moved, and the tears would run down his wrinkled cheeks. It is recorded that he was very grateful for any kindness shown him; and when Lieutenant Thorpe left the ship to return to England he expressed the most intense sorrow, crying the whole day, and repeating the officer's name in piteous accents. This, it was noted, was not merely a temporary affection. When, a year later, the Calliope was leaving the New Zealand station, he sent his favourite a very handsome mat, begging the officer by whom it was sent to tell Lieutenant Thorpe how glad he would be to see his face once more, and how well he would treat him now that he was free. Similarly, when Lieutenant McKillop was proceeding home, Te Rauparaha took him aside and entreated him to go, on reaching England, and convey to Queen Victoria his regard for her and express his keen desire to see her, only his great age and the length of the voyage standing between him and the consummation of that desire. "He hoped, however, she would believe that he would always be a great and true friend of hers, and use all his influence with his countrymen to make them treat her subjects well, and that, when he became free again, there would be no doubt as to his loyalty, as he would himself, old as he was, be the first to engage in a war against any who should offend her or the Governor, of whom he always spoke with the greatest respect." During his captivity the news of the outbreak of the war in the Sutlej reached the Colony, and, noticing the excitement on board the Calliope, he asked to be informed of the contents of the papers giving details of the battles. In this subject he maintained the liveliest interest; and, when he had sufficiently grasped the details, he was perceptibly impressed by the magnitude of the armies engaged and the tremendous resources of the Empire, about which he, in common with all natives, had been distinctly incredulous. That his release was marked by no exhibition of resentment is at least something to his credit, and the ease with which he afterwards adapted himself to the strangely altered order of things is proof that his nature was capable of absorbing higher ideals than are taught in savage philosophy, although it is doubtful if he ever reached the purer heights attained by a clear conception of the beatitudes of the Christian religion.

In the life of Te Rauparaha there is much that is revolting and incapable of palliation. But, always remembering his savage environment, we must concede to him the possession of qualities which, under more enlightened circumstances, would have contributed as fruitfully to the uplifting of mankind as they did to its destruction. His superiority over his fellows was mental rather than physical; his success lay in his intellectual alertness, his originality, strategic foresight, and executive capacity. He was probably a better diplomat than he was a general, but he had sufficient of the military instinct to make him a conqueror. And if, in the execution of his conquests, the primary object of which was to find a safe home for his people, the weaker tribes went down, history was but repeating amongst the Maoris in New Zealand the story which animate nature is always and everywhere proclaiming, and which, in the cold language of the philosophers, is called "the survival of the fittest."

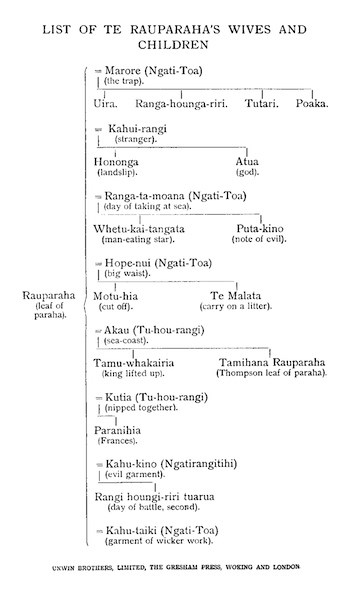

LIST OF TE RAUPARAHA'S WIVES AND CHILDREN

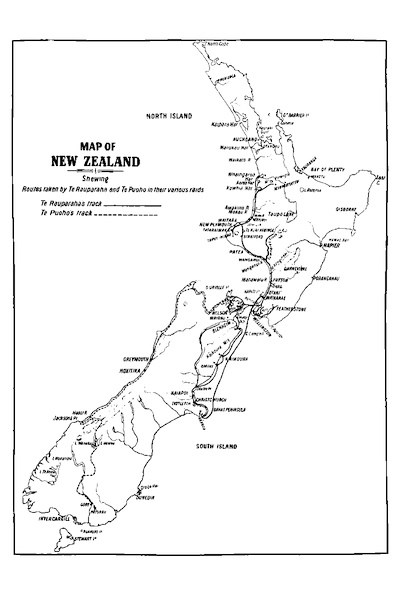

MAP OF NEW ZEALAND

Shewing routes taken by Te Rauparaha and Te Puoho in their various raids

1

"The distinguishing characteristic of the Marquesan Islanders, and that which at once strikes you, is the European cast of their features – a peculiarity seldom observable among other uncivilised peoples. Many of their faces present a profile classically beautiful, and I saw several who were in every respect models of beauty" (Melville).

2

"I found that the Natives had not formed the slightest idea of there being a state of future punishment. They refuse to believe that the Good Spirit intends to make them miserable after their decease. They imagine all the actions of this life are punished here, and that every one when dead, good or bad, bondsman or free, is assembled on an island situated near the North Cape, where both the necessaries and comforts of life will be found in the greatest abundance, and all will enjoy a state of uninterrupted happiness" (Earle).

3

"It is most certain that the whites are the aborigines. Their colour is, generally speaking, like that of the people of Southern Europe, and I saw several who had red hair. There were some who were as white as our sailors, and we often saw on our ships a tall young man, 5 feet 11 inches in height, who, by his colour and features, might easily have passed for a European" (Crozet's Description of the Maoris at the Bay of Islands).

4

The knowledge which the Polynesians possessed of the Southern sea, and their skill as navigators, was such that when "the fleet" set out from Rarotonga, they did not go to discover New Zealand, but they went with the absolute certainty of finding it.

5

"Man of the land, native, aboriginal." Probably these people were a mixture of the Melanesian and Polynesian types.

6

On this occasion Hotu-nui is credited with having addressed his people in the following terms: "Friends, hearken! Ours was the first canoe to land in New Zealand before any of you had arrived here. But let this be the proof as to which of our canoes landed first. Let us look at the ropes which the various canoes tied to the whale now before us, and also let us look at the branches of the trees which each have put up in building an altar, then the owners of the rope which is the driest and most withered, and of the altar the leaves of which are the most faded, were the first to land on the coast of the country where we now reside."

7

After the canoe left Whanga-poraoa the first stopping-place was at Whare-nga, where the crew amused themselves with various games on the beach. To mark the spot, one legend has it, they placed one large stone on top of another, while a second story has it that this monument, which is still existent and is called Pohatu Whakairi, represents one of the crew who was turned into stone. The next point of interest was Moe-hau, now known as Cape Colville. They then landed at Te Ana-Puta, where, it is said, the canoe was moored to a natural arch of rock jutting into the sea. For some reason the anchor was left at a spot between Wai-hou and Piako, and under the name of Te pungapunga (the pumice stone) is still to be seen on the coast by those who are curious enough to look for it. The course was then deflected slightly to the west, and the canoe crossed to Whaka-ti-wai and coasted along the mainland past Whare-Kawa, where, it is said, Marama, one of the wives of Hoturoa, desired to be put ashore with one of her male slaves. Here they were left, and, according to one version of the tradition, it was her misconduct with this slave which prevented the crew dragging the Tainui over the portage at Otahuhu. The canoe then went on, some accounts say, as far as the North Cape, and others seem to imply that she was shortly afterwards put about and, returning into the Hauraki Gulf, sailed past the islands of Waiheke and Motu-Korea, until land was once more made at Takapuna.

8

Now called Mount Victoria or "Flagstaff Hill."

9

Waitemata may be interpreted as "the waters of volcanic obsidian," no doubt a reference to the eruptive disposition of Mount Rangitoto.

10

Otahuhu signifies "ridge-pole." This portage is only 3,900 feet long and 66 feet high.

11

There are different versions of this tradition, some attributing the transfixing of the canoe to Marama, others crediting her with releasing it. The version given in the late Sir George Grey's Polynesian Mythology has been here adopted.

12

Some authorities are of opinion that the Tainui was not taken across the portage at Otahuhu (ridge-pole), and they base this contention upon the fact that no traditional marks have been left inside the Manukau harbour. All the points of interest which have been handed down, and are remembered, are on the sea coast; and from this circumstance it is argued that the canoe was never in Manukau harbour at all. Others say that some of the skids of Tainui were left at South Manukau Heads.

13

As they were passing the mouth of the Waikato, the priest of the canoe, noticing that the river was in flood, named it by calling out "Waikato, Waikato, kau." Further on, noticing that there were no landing-places, he threw his paddle at the face of the cliff and exclaimed, "Ko te akau kau" (all sea coast). The paddle is said to be still embedded in the face of the rock, and is one of the traditional marks by which the course of the Tainui can be traced. At the entrance of Kawhia Harbour they ran into a shoal of fish, and the priest gave this haven its present name by exclaiming "Kawhia kau." Another account is that the name comes from Ka-awhi, to recite the usual karakia on landing on a new shore, to placate the local gods.

14

The distance between these stones is 86 feet, indicating the probable length of the Tainui canoe.

15

Now called Te Fana-i-Ahurei (or, in Maori, Te Whanga-i-Ahurei, the district of Ahurei).

16

The Tainui brought the species of kumaras known as Anu-rangi (cold of heaven) and the hue or calabash. Those planted by Marama did not come up true to type, but those planted by Whakaoti-rangi, another of the chief's wives, did.

17

"I reckon this country among the most charming and fertile districts I have seen in New Zealand" (Hochstetter).

18

The natives call them Whenuapo.

19

His full name was Raumati-nui-o-taua. His father was Tama-ahua, who is reputed to have returned to Hawaiki from New Zealand, and his mother was Tauranga, a Bay of Plenty woman.

20

The date of this incident has been approximately fixed at a. d. 1390, or forty years after the arrival of "the fleet."

21

"It is to be presumed that Raumati's relatives and friends at Tauranga made his cause their own, for they met the Arawa people somewhere near Maketu, where a great battle was fought. Raumati's party, though successful at first, were defeated, and their leader killed by the power of makutu, or witch-craft, for Hatu-patu, the Arawa chief, caused a cliff to fall on him as he retreated from the battle, and thus killed him" (Polynesian Journal).

22

Braves.

23

Waitohi had other children, one of whom, Topeora, afterwards became the mother of Matene Te Whiwhi, one of the most influential and friendly chiefs on the west coast of the North Island. Topeora is perhaps more famed than any other Maori lady, for the number of her poetical effusions, which generally take the form of kaioraora, or cursing songs, in which she expresses the utmost hatred of her enemies. Her songs are full of historical allusions, and are therefore greatly valued. She also bore the reputation of being something of a beauty in her day.

24

There appears to be some doubt as to the exact locality of Te Rauparaha's birth, some authorities giving it as Maungatautari and others as Kawhia.

25

Marore was killed by a member of the Waikato tribe – it is said, at the instigation of Te Wherowhero – while she was attending a tangi in their district, about the year 1820.

26

War party.

27

The traditional accounts of the Maoris have it that at this period Te Rauparaha was "famous in matters relative to warfare, cultivating generosity, welcoming of strangers and war parties."

28

This tribe was afterwards partially exterminated during the raids of Hongi and Te Waharoa.

29

"When Paora, a northern chief, invaded the district of Whanga-roa, in 1819, the terrified people described him as having twelve muskets, while the name of Te Korokoro, then a great chief of the Bay of Islands, who was known to possess fifty stand of arms, was heard with terror for upwards of two hundred miles beyond his own district" (Travers).

30

"If we take the whole catalogue of dreadful massacres they (the New Zealanders) have been charged with, and (setting aside partiality for our own countrymen) allow them to be carefully examined, it will be found that we have invariably been the aggressors: and when we have given serious cause of offence, can we be so irrational as to express astonishment that a savage should seek revenge?" (Earle).

31

Marsden, writing of this time, says that such was the dread of the Maoris that he was compelled to wait for more than three years before he could induce a captain to bring the missionaries to New Zealand, as "no master of a vessel would venture for fear of his ship and crew falling a sacrifice to the natives." As an extra precaution, all vessels which did visit the country were supplied with boarding nets.