полная версия

полная версияBuffon's Natural History. Volume X (of 10)

“I resolved on separating, as exactly as possible, these different substances, by means of the loadstone, and to put aside the parts most attractable by the loadstone, from those which were less, and both from those which were not so at all; then to examine each substance particularly, and to submit them to different chemical and mechanical heats.

“I separated these parts of the platina which were briskly attracted at the distance of two or three lines; that is to say, without the contact of the loadstone; and for this experiment I made use of a good fictious magnet; I afterwards touched the metal with this magnet, and carried off all that would yield to the magnetical force. Being scarcely any longer attractable, I weighed what remained, and which I shall call No. 4; it was twenty-four grains; No. 1, which was the most sensible to the magnet, weighed four grains; No. 2 weighed the same; and No. 3, five grains

“No. 1, examined by the magnifying glass, presented only a mixture of metallic parts, a white sand bordering on the greyish, flat and round, or black vitriform sand, resembling pounded scoria, in which very rusty parts are perceptible: in short, such as the scoria of iron presents after having been exposed to moisture.

“No. 2 presented nearly the same, excepting that the metallic parts predominated, and that there were very few rusty particles.

“No. 3 was the same, but the metallic parts were more voluminous; they resembled melted metal which had been thrown into water to be granulated; they were flat, and of all sorts of figures, rounded on the corners.

“No. 4, which had not been carried off by the magnet (but some parts of which still afforded marks of sensibility to magnetism, when the magnet was moved under the paper where they were in), was a mixture of sand, metallic parts, and real scoria, friable between the fingers, and which blackened in the same manner as common scoria. The sand seemed to be composed of small rock, topaz, and cornelian chrystals. I broke some on a steel, and the powder was like varnish, reduced into powder; I did the same to the scoria; it broke with the greatest facility, and presented a black powder which blackened the paper like the common.

“The metallic parts of this last (No. 4) appeared more ductile under the hammer than those of No. 1, which made me imagine they contained less iron than the first: from whence it follows, that platina may possibly be no more than a mixture of iron and gold made by Nature, or perhaps by the hands of men.

“I endeavoured to examine, by every possible means, the nature of platina: to assure myself of the presence of iron of platina by chemical means, I took No. 1, which was very attractable by the magnet, and No. 4, which was not; I sprinkled them with fuming spirit of nitre; I immediately observed it with the microscope, but perceived no effervescence: I added distilled water thereon, and it still made no motion, but the metallic parts acquired new brilliancy, like silver: I let this mixture rest for five or six minutes, and having still added water, I threw some drops of alkaline liquor saturated with the colouring matter of Prussian blue, and very fine Prussian blue was afforded me on the first.

“No. 4, treated in the same manner, gave the same result. There are two things very singular to remark in these experiments; first, that it passes current among chemists who have treated on the platina, that aquafortis, or spirit of nitre, has no action on it. Yet, as I have just observed, it dissolves it sufficiently, though without effervescence, to afford Prussian blue, when we add the alkaline liquor phlogisticated and saturated with the colouring matter, which, as is known, participates iron into Prussian blue.

“Secondly, Platina, which is not sensible to the magnet, does not contain less iron, since spirits of nitre dissolves it enough, and without effervescence, to make Prussian blue. Whence it follows, that this substance, which modern chemists, perhaps too greedy of the marvellous, and too willing to give something novel, have considered as a ninth metal, may possibly be only a mixture of gold and iron.

“Without doubt there still require many experiments to determine how this mixture has taken place, if it be the work of Nature or the effects of some volcano, or simply the produce of the Spaniards’ labours in the New World to acquire gold in the mines of Peru.

“If we rub platina on white linen it blackens it like common scoria, which made me suspect that it was the parts of iron reduced into scoria which are found in this platina, and give it this colour, and which seem, in this state, only to have undergone the action of a violent fire. Besides, having a second time examined platina with my lens, I perceived therein different globules of liquid mercury, which made me suppose that platina might be the produce of the hands of man, in the following manner: – Platina, as I have been told, is taken out of the oldest mines in Peru, which the Spaniards explored after the conquest of the New World. In those dark times only two methods were known of extracting gold from the sands which contained it; first, by an amalgama with mercury; secondly, by drying it. The golden sand was triturated with quicksilver, and when that was judged to be loaded with the greatest part of the gold, the sand was thrown away, which was named crasse, as useless and of no value.

“The other method was adopted with as little judgment; to extract it they began by mineralising auriferous metals by means of sulphur, which has no action on gold, the specific weight being greater than that of other metals: but to facilitate its precipitation iron was added, which loaded itself with the superabundant sulphur, and this method is still followed. The force of fire vitrifies one part of the iron, the other combines itself with a small portion of the gold, or even silver, which mixes with the scoria, from whence it cannot be drawn but by strong fusions, and being well instructed in the suitable intermediums which are made use of. Chemistry, which is now arrived to great perfection, affords, in fact, means to extract the greatest part of this gold and silver: but at the time when the Spaniards explored the mines of Peru, they were, doubtless, ignorant of the art of mining with the greatest profit; besides, they had such great riches at their disposal that they, probably, neglected the means which would have cost them trouble, care, and time; there is much reason therefore to conclude that they contented themselves with a first fusion, and threw away the scoria as useless, as well as the sand which had escaped the quicksilver, and perhaps they made a mere heap of these two mixtures, which they regarded as of no value.

“These scoria contained gold and silver, iron under different states, and that in different proportions unknown to us, but which, perhaps, are those that gave origin to the platina. The globules of quicksilver which I observed, and those of gold which I distinctly saw, with the assistance of a good lens, in the platina I had in my hands, have given birth to the ideas which I have written on the origin of this mineral; but I only give them as hazardous conjectures. To acquire some certainty we must know precisely where the platina mines are situated, and examine if they have been anciently explored, whether it be extracted from a new soil, or if the mines be only rubbish, and to what depth they are found; and, lastly, if they have any appearance of being placed by the hands of man there or not, which alone can verify or destroy the conjectures I have advanced.”4

These observations of Comte de Milly confirm mine in almost every point. Nature is the same, and presents herself always the same to those who know how to observe her: thus we must not be surprized that, without any communication, we observed the same things, and deduced the same consequence therefrom; that platina is not a new metal, different from every other, but a mixture of iron and gold. To reconcile his observations still more with mine, and to enlighten, at the same time, the doubts which remain on the origin and formation of platina, I have thought it necessary to add the following remarks:

1. The Comte de Milly distinguishes three kinds of matters in platina, namely, two, metallic, and the third, non-metallic, of a chrystalline form and substance. He observed, as well as I, that one of the metallic matters is very attractable by the magnet, and the other but little, or not at all. I mentioned these two matters as well as he, but I did not speak of the third, which is not metallic, because there was none, or very little, on the platina on which I made my observations. It is possible that the platina which the Comte made use of was not so pure as mine, which, I observed with the greatest care, and in which I saw only some small transparent globules, like white melted glass, which were united to the particles of platina, or ferruginous sand, and which were carried any where by the magnet. These transparent globules were very few, and in eight ounces of platina which I narrowly inspected with a very strong lens, I never perceived regular crystals. It rather appeared to me that all the transparent particles were globulous, like melted glass, and all attached to metallic parts; nevertheless, as I did not in the least doubt the veracity of the Comte de Milly’s observation, who observed chrystalline particles of a regular form, and in a great number, in his platina, I thought I ought not to confine myself solely to the examination of that platina of which I have spoken; and finding some in the king’s cabinet, M. Daubenton and I examined it together: this appeared to be much less pure than that we had before made our experiments on; and in it we remarked a great number of small prismatic and transparent crystals, some of a ruby colour, others of a topaz, and others perfectly white, which convinced us of the correctness of the Comte de Milly in his observations; but this only proves that there are some mines of platina much more pure than others, and that in those which are the most so, none of these foreign bodies are found. M. Daubenton also remarked some grains flat at bottom and rough at top, like melted metal cooled on a plain, and I very distinctly saw one of these hemispherical grains, which might indicate that platina is a matter that has been melted by the fire; but it is very singular, that in this matter, if melted by fire, small crystals, topaz, and rubies, are found; and I know not whether we ought not to suspect fraud in those who supplied this platina, who, to increase the quantity, mixed it with these crystalline sands, for I never met with these crystals but in one half pound of platina given me by the Comte de Angilliviers.

2. I, as well as Comte de Milly, found gold sand in platina; it is readily discovered by its colour, and because it is not magnetical; but I own that I never perceived the globules of mercury which he states to have done; yet I do not mean therefore to deny their existence, only that it appears to me that the sand of gold meeting with the globules of mercury, in the same matter, they might be soon amalgamated, and not retain the colour of gold, which I have remarked in all the gold sand that I could find in half a pound of platina; besides, the transparent globules, which I have just spoken of, resemble greatly the globules of live and shining mercury, insomuch that at the first glance it is easy to be deceived in them.

3. There were by no means so many tarnished and rusty parts in my first platina as in that of Comte de Milly’s, nor was it properly a rust which covered the surface of those ferruginous particles, but a black substance produced by fire, and perfectly similar to that which covers the surface of burnt iron. But my second platina, that which I had from the royal cabinet, had a mixture of some ferruginous parts, which under the hammer were reduced into a yellow powder, and had all the characters of rust. This platina therefore of the royal cabinet, and that of Comte de Milly, resembling in every respect, it is probable that they proceeded from the same part, and by the same road. I even suspect that both had been sophisticated and mixed nearly one half with foreign crystalline and ferruginous rusty matters, which are not to be met with in the natural platina.

4. The production of Prussian blue by platina appears evidently to prove the presence of iron in those parts even of this mineral which are the least attractable to the magnet, and at the same time confirms what I have advanced on the intimate mixture of iron in its substance. The flowing of platina by spirits of nitre, also proves that although it has no sensible effervescence, this acid attracts the platina in an evident manner; and the authors who have asserted the contrary, have followed their common track, which consists in looking on all actions as null which do not produce an effervescence. These second experiments of the Comte de Milly would appear to me very important, if they succeeded always alike.

5. We must however admit that many essential points of information are wanting to pronounce affirmatively on the origin of platina. We know nothing of the natural history of his mineral, and we cannot too greatly exhort those who are able to examine it on the spot, to make known their observations; and until that is done we must confine ourselves to conjectures, some of which appear only more probable than others. For example, I do not imagine platina to be the work of man. The Mexicans and Peruvians knew how to cast and work gold before the arrival of the Spaniards, and they were not acquainted with iron, which nevertheless they must have employed in a great quantity. The Spaniards themselves did not establish furnaces in this country when they first inhabited it to fuse iron. There is, therefore, every reason to conclude, that they did not make use of the filings of iron for the separation of gold, at least in the beginning of their labours, which does not go above two centuries and a half back; a time much too short for so plentiful a production as platina, which is found in large quantities in many places.

Besides, when gold is mixed with iron, by fusing them together, we may always, by a chemical process, separate them, and extract the gold: whereas, hitherto, chemists have not been able to make this separation in platina, nor determine the quantity of gold contained in this mineral. This seems to prove, that gold is united with it in a more intimate manner than the common alloy, and that iron is also in it, in a different state from that of common iron. Platina, therefore, appears to me to be the production of nature, and I am greatly inclined to think, that it owes its first origin to the fire of volcanos. Burnt iron, intimately united with gold by sublimation, or fusion, may have produced this mineral, which having been at first formed by the action of the fiercest fire, will afterwards have felt the impression of water, and reiterated frictions, which have given it the form of blunt angles. But water alone might have produced platina; for supposing gold and iron divided as much as possible by the humid mode, their molecules, by uniting, will have formed the grains which compose it, and which from the heaviest to the lightest contain gold and iron; the proposition of the chemist who offers to render nearly as much gold as they shall furnish him with platina, seems to indicate, that there is, in fact, only 1/11 of iron to 10/11 of gold in this mineral, or possibly less. But the nearly of this chemist is perhaps a fifth, or fourth, and indeed, if he could realize his promise to a fourth, it would be doing a great deal, and no vain boast.

Being at Dijon the summer of 1773, the Academy of Sciences and Belles Letters, of which I have the honour to be a member, expressed a desire of hearing my observations on platina; and having complied, M. de Morveau resolved to make some experiments on this mineral; for which purpose I gave him a portion of that which I had attracted by the loadstone, and also some which I had found insensible to magnetism, requesting him to expose it to the strongest fire he could possibly make. Some time after, he sent me the following experiments, which he was pleased to subjoin to mine.

“Monsieur the Comte de Buffon, in a journey to Dijon, in the summer of 1773, having caused me to remark in half a drachm of plati na, which M. de Baume had sent him in 1768, grains in form of buttons, others flatter, and some black and scaly; and having separated by the loadstone those which are attractable from those which appeared not so, I tried to form Prussian blue with both. I sprinkled the fuming nitrous acid on the non-attractable parts, which weighed 21/2 grains. Six hours after I put distilled water on the acid, and sprinkled alkaline liquor, saturated with a colouring matter; however there was not a single atom of blue, the platina had only a little more brightness. I alike sprinkled the fuming acid on the remaining platina, part of which was attractable, the same Prussian alkali precipitated a blue feculency, which covered the bottom of a pretty large bason. The platina, after this operation, shewed like the first. I washed and dried it, and found it had not lost 1/4 of a grain, or 1/138 part; having examined it in this state I perceived a grain of beautiful yellow, which was pure gold.

“M. de Fourcy had lately told the world, that the dissolution of gold was thrown down in a blue precipitate by the Prussian alkali, and had placed this circumstance in a table of affinity; I was tempted to repeat this experi ment, and sprinkled, in consequence, the phlogisticated alkaline liquor in the dissolution of gold, but the colour of this dissolution did not change, which made me suspect that the dissolution of gold made use of by M. de Fourcy might possibly not have been so pure.

“At the same time the Comte de Buffon having given me a sufficient quantity of platina to make further assays, I undertook to separate it from all foreign bodies by a good front; and I have here subjoined the processes and their results.

EXPERIMENTS“I. Having put a drachm of platina, in a cupel, into a furnace, I kept up the fire two hours, when the covers sunk down, the supporters having run, nevertheless the platina was only agglutinated; it stuck to the cupel, and had left spots of a rusty colour. The platina was then tarnished, even a little black, and had only augmented a quarter of a grain in weight; a quantity very small in comparison with that which other chemists have observed. What surprised me still more was, that this drachm of platina, as well as that I used for other experiments, had been successively carried away by the load stone, and made a portion of 6/7 of eight ounces, of which the Comte de Buffon has before spoken.

“II. Half a drachm of the same platina, exposed to the same fire in a cupel, was also agglutinated; I adhered to the cupel, on which it had left spots of a rusty colour; the augmentation of weight was found to be nearly in the same proportion, and the surface as black.

“III. I put this half drachm into a new cupel, but instead of a cover I placed over it a leaden crucible. This I kept in the most extreme heat for four hours; when it was cooled I found the crucible soldered to the support, and having broken it I perceived that nothing had penetrated into the internal part of the crucible, which appeared to be only more glossy than before. The cupel had preserved its form and position; it was a little cracked, but not enough to admit of any penetration; the platina was also not adherent to it, though agglutinated, but in a much more intimate manner than in the first experiments; the grains were less angular, the colour more clear, and the brilliancy more metallic. But what was the most remarkable during the operation, there issued from its surface, probably in the first moments of its refrigeration, three drops of water, one of which, that arose perfectly spherical, was carried up on a small pedicle of the vitreous and transparent matter. It was of an uniform colour, with a slight tint of red, which did not deprive it of any transparency; the smallest of the other two drops had likewise a pedicle, and the other none, but was only attached to the platina by its external surface.

“IV. I endeavoured to assay the platina, and for that intent put a drachm of the grains taken up by the loadstone into a cupel, with two drachms of lead. After having kept up a very strong fire for two hours, I found an adherent button, covered with a yellowish and spungeous crust of two drachms twelve grains weight, which announces that the platina had retained one drachm twelve grains of lead. I put this button into another cupel in the same furnace, observing to turn it, by which it only lost twelve grains in two hours; its colour and form were very little changed. The same piece of platina was put into Macquer’s furnace, and a fire kept up for three hours, when I was obliged to take it out, because the bricks began to run. The platina was become more metallic, but it, nevertheless, adhered to the cupel, and this time it lost 34 grains. I threw it into the fuming nitrous acid to assay it, and there arising a little effervescence, I added distilled water thereon. The platina lost two grains, and I remarked some small holes, like those which its flying off might occasion.

“There then remained only 22 grains of lead in the platina. I began to form a hope of vitrifying this remaining portion of lead, for which purpose I put the same piece of platina into a new cupel, and by the care I took for the admission of air, and other precautions, the activity of the fire was so greatly augmented that it required a supply every eleven minutes; to this degree of heat we kept for four hours, and then permitted it to cool.

“I perceived the next morning that the leaden crucible had resisted, and that the supporters were only glazed by the cinders. I found a piece in the cupel, not adhering, of a uniform colour, approaching more the colour of tin than any other metal, but only a little ragged. It weighed exactly one drachm. All, therefore, announced that this platina had endured an absolute fusion, and that it was perfectly pure, for if we suppose it still contained lead, we must then admit that it had lost exactly as much of its substance as it had gained of foreign matter; and such a precision cannot be the effect of pure chance.

“I passed several days with M. Buffon, whose company has the same charms as his style, and whose conversation is as complete as his books: I took a pleasure in presenting him with the production of our essays; we examined them together, and observed, First, that the drachm of platina, agglutinated by these experiments, was not attractable by the loadstone; that, nevertheless, the magnetical bar had an action on the grains that were loosened from it.

“2. The half drachm of the third experiment was not only attractable in the mass, but the grains of gold separated therefrom did not themselves give any signs of magnetism.

“3. The platina of the fourth experiment was absolutely insensible to the loadstone.

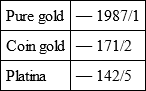

“4. The specific weight of this piece was determined by a good hydrostatical balance, and being, for the greater certainty, compared to coined and to other very pure gold, used by M. Buffon in his experiments, their density was found, with water, in which they were plunged,

“5. This piece of platina was put upon steel to try its ductability; it supported the hammer very well for a few strokes; its surface became flat and even, a little smooth in the parts which were struck, but it split soon after, and nearly a sixth part separated. The fracture presented many cavities, some of which had the whiteness and brilliancy of silver, and in others we remarked several points like chrystalization; the tops of these points examined with the lens, was a globule absolutely similar to that of the third experiment. All the other parts of this piece of platina were compact, the grain finer and closer than the best brass, which it resembled in colour. We offered several of these pieces to the loadstone, but not one was attracted thereby. We powdered them again in an agate mortar, and then remarked that the magnetical bar raised up some of the smallest every time they are placed under it.

“This new appearance of magnetism was so much the more surprising, as the grains were detached from the agglutinated mass of the second experiment, which seemed to have lost all sensibility at the approach and contact of the loadstone. In consequence we again took some of these grains, which were alike powdered, and soon perceived the smallest parts sensibly attach themselves to the magnetic bar. It is impossible to attribute this effect to the smoothness of the bar, or to any other cause foreign to magnetism. A piece of smooth iron, applied in the same manner on the parts of this platina did not raise up a single grain.